Genealogist Lynn Serafinn discusses the history of the Maturi family of Pinzolo in Val Rendena, and their expansion into Mezzana, Cavizzana and Caldes in Val di Sole.

Want to keep this article to read offline? You can purchase it as a 25-page printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, charts, footnotes and resource list.

Price: $3.00 USD.

Available in Letter size or A4 size.

CLICK HERE to buy this article in the ‘Digital Shop’, where you can also browse for other genealogy articles.

Introduction

I have a personal fascination with surnames, and especially the surnames of Trentino.

What I find most interesting about the study of surnames is that they are actually rather recent innovations. Surnames as we know them didn’t really become cultural conventions until the 1400s, and even then, they were still very much in a state of flux, even into the 1600s. Thus, it is not so unthinkable that we might be able to discover the origins of a surname. Where was it ‘born’? When did it first appear? What did it mean? And (sometimes), who was the earliest known patriarch of that family? To me, this is a tantalising challenge.

But how do we approach such a challenge? The parish records, upon which most of us rely for genealogical research, did not become mandatory practice until the Council of Trento in the 1560s. And, sadly, not all the early registers for the 400+ parishes in Trentino have survived the ravages of time.

Fortunately, many Trentino parishes and comune have archives of ‘pergamene’ (legal parchments and charters, typically drafted by notaries), which sometimes go back into the 1200s. These kinds of documents (especially those drafted from the 1400s or later, when surnames were in use) can often help us to piece together fragments of evidence to form a clearer picture of the families and communities living in rural Trentino in the late medieval era.

In this article, we will be looking at the surname MATURI, which appears to have its roots in the village of Pinzolo in Val Rendena. We will examine the available evidence to gain an understanding of how long that family had been living in Pinzolo before the beginning of the surviving parish records. Later, we will explore how branches of the family settled in Val di Sole, first in Mezzana, and later in Cavizzana and Caldes.

During our exploration, we will also look at the lives of a few notable Maturi personalities throughout history.

Acknowledgements

In addition to the many references cited throughout this report, I would personally like to thank my colleague James R. Caola for his valuable input and knowledge of the histories of Pinzolo families, as well as Gloria Maturi for her kind contribution of research materials. Last but not least, I would like to thank Robert Jusko for kindly proofreading the text.

Geographic Orientation

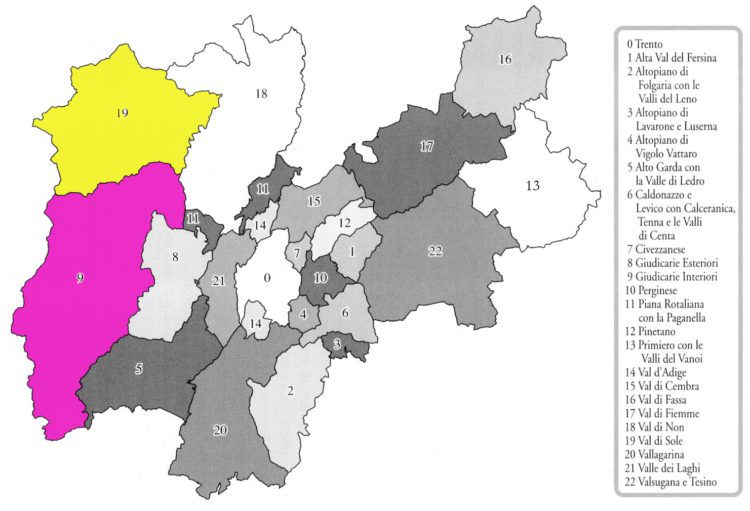

Val Rendena is a ‘sub valley’ of the larger valley of Giudicarie Interior in the western part of the province; I have highlighted Giudicarie Interiore in PINK in the map below. Val di Sole lies to the north, highlighted in YELLOW.[i]

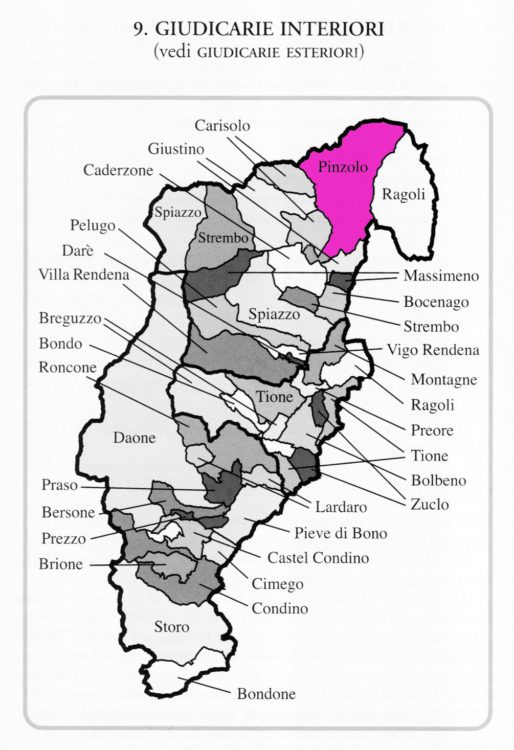

Pinzolo is at the northernmost ‘bulge’ of Giudicarie Interior, near the south-eastern border of Val di Sole:

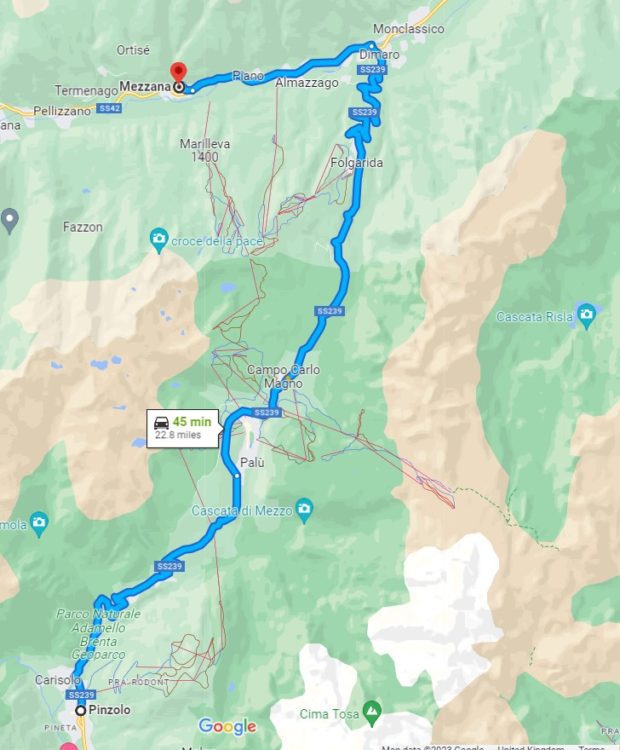

As we will see later, Mezzana is only about 20 miles north of Pinzolo, albeit across mountainous terrain.

Theories on Linguistic Origins of the Surname

Linguistic historian Aldo Bertoluzza says this surname is derived from the attribute of being ‘mature’, in the sense of been an adult, but also in the sense of being a ‘seasoned’ individual,[ii] like a fine wine or aged wood. However, there also seems to have been a personal name ‘Maturino’ in the medieval era, so it is possible ‘Maturi’ is a patronymic that was adopted by a family whose patriarch had the name or nickname ‘Maturino’. [iii] But even if that is the case, I have not seen ‘Maturino’ appearing as a personal name within the family in any of the surviving records for this family.

Spelling Variations

Matturi; Maduri; Madur; de Maturi; de Maturis

In early records, we find the surname spelled in early variant forms. For several decades in the 1600s, it will appear in its Latin form ‘de Maturis’ or ‘de Maturi’, and then we find it in its dialect form ‘Madur’[iv], until it finally settled into its permanent form ‘Maturi’ in the 1700s.

Origins of the Maturi Family

Although there has been much popular hearsay claiming that the Maturi originally came from outside the province of Trentino (apparently, people have guessed everything from Lombardia, to Rome, to Naples, to Germany, and even Japan), there really is no documentary evidence to support any of these speculations. All the evidence I have found supports the assumption that the surname has its origins in Pinzolo in Val Rendena, where we know it has existed for close to 600 years. Because surnames weren’t really yet in use in Trentino earlier than the 1400s, I would go so far as to say the surname was ‘born’ in Pinzolo.

Author Carla Maturi tells us that the first written record with the Maturi surname is a pergamena (legal parchment) dated 1527, which is conserved in the historical archives of the comune of Pinzolo.[v] Historian Giacomo Maturi, however, tells us there is an earlier reference to Maturi in a pergamena from the 1400s in the same archives. He adds that this particular family was nicknamed ‘Todesch’, which might lead one to imagine a German or Austrian connection (Tedesco = German in Italian), but he admits this is too tenuous to say this with certainty.[vi] In my own experience, such a reference could just as feasibly be nickname given to someone who had a German-speaking mother, or who had lived in German-speaking South Tyrol for a period of time, etc.

Although I have not seen the document Giacomo Maturi mentioned, I have found a promissory note drafted on 20 October 1456, we find the name of a ‘Bonomo, son of the late Martino Maturi of Presson’ agreeing to pay a debt to Giorgio, son of the late dom. Riprando of Castel Cles.[vii] Presson is frazione of Monclassico in Val di Sole, not Val Rendena; but it is only about 20 miles away from Pinzolo, so it is certainly possible Bonomo was from Pinzolo and had moved to Presson (or vice versa).

The Early Maturi of Pinzolo

Trying to piece together a genealogical study for the families of Pinzolo is challenged by the fact that a horrific fire in 1913 destroyed many of the early parish records, along with half the town. The surviving baptismal records begin in 1640 (albeit with some gaps), but the marriage and death records do not begin until the late 1770s. Some Pinzolo births and marriages (including some Maturi) for the 1630s can be found in the baptismal register for the neighbouring parish of Giustino. My colleague James R. Caola says the Giustino death records in that era a ‘very patchy’ due to the plague of 1630. Random marriages for Pinzolo can occasionally be found in the records for Spiazzo and Tione.

Using notary documents, however, we find several references to Maturi in Pinzolo throughout the 1500s, which do indeed point to them having been there by the 1400s. Bertoluzza tells us there is a document dated 1527 that mentions Giovanni Bartolomeo Maduri of Pinzolo, but he does not give the source information, and I have not yet been able to locate it. In my own research, I found a marriage record in the register for Tione, dated after August 1584,[viii] for a Bartolomeo Maduri of Pinzolo and Antonia Ballardini of Ragoli. Bartolomeo’s father Antonio was deceased at the time of the marriage, which helps us estimate that he may have been born around 1520-1525.

In his Biblioteca Tirolese, Giangrisostomo Tovazzi cites a reference to a Jesuit priest and writer named Pietro Maturi, who ‘flourished’ in the 1500s,[ix] whom he apparently presumes was from the Maturi of Pinzolo, but he offers no details about him. A bit later, we find two Maturi priests from Pinzolo, namely Giovanni Paolo Maturi, who was active in his profession at least between 1610-1631 (so he would have been born no later than 1585), as well as a Paolo Maturi, who was active at least between 1631-1645.[x]

Additionally, in the Archivi Storici del Trentino database, we find a legal document dated 2 August 1605 wherein a ‘Lorenzo, son of the late Giovanni Maturi called “il Beatrice”, of Pinzolo’ cited as one of several witnesses at the signing of an agreement between the villages of Fisto, Ches, and Bocenago.[xi] A few years later, on 23 August 1611, we find this same Lorenzo acknowledging receipt of payment he received from the consuls of Bocenago.[xii] In a document drafted in Stenico a few months later, we again find Lorenzo cited as a witness at a legal dispute over the rights for cutting wood on a mountain in the area.[xiii] As we can presume Lorenzo was a legal adult in 1605, we known he would have been born no later than 1580, and his late father Giovanni would have been born sometime in the mid-1500s.

The Use of Soprannomi as a Clue

‘Il Beatrice’ is a soprannome, a convention that families in Italy use in addition to their surname, to distinguish different branches of families who share the same surname. Giacomo Maturi comments that there were no Maturi soprannome in the early Pinzolo records, but this is only because the priest at Pinzolo did not bother to record them. The documents above clearly document the soprannome ‘il Beatrice’, and we also find two children with this same soprannome born in the 1630s, recorded in the register at Giustino. Evidently, this line had moved to the frazione of Baldino by this time.[xiv] In addition to ‘Il Beatrice’, we also find another soprannome – ‘Donatis’ – in the 1630s, again recorded in the register for Giustino.[xv]

The presence of these soprannomi clearly tell us that there were at least two branches of the Maturi living in Pinzolo by the end of the 1500s. To have become this articulated, the surname had to have been present at least a few more generations, likely stretching into the 1400s. If we also consider the possibility that ‘Todesch’ (as cited by Giacomo Maturi) may also have been an actual soprannome rather than a personal nickname, the family may have already had multiple branches in Pinzolo by the 1400s.

These clues support my personal belief that the surname was indeed ‘born’ in Pinzolo, as we don’t find surnames in common practice before this era.

The Notable Maturi ‘Beatrice’ Line in Baldino

In an article from 2003, author Giacomo F. Maturi tells us that, in the 1600s, Baldino was a distinct community from Pinzolo, albeit they both were part of the parish of Pinzolo. He also says that the Baldino line of Maturi (who appear to have been the ‘Beatrice’ line) soon rose above the level of contadini (farmers), to become wealthy and highly educated, with several generations of notaries during that century.[xvi]

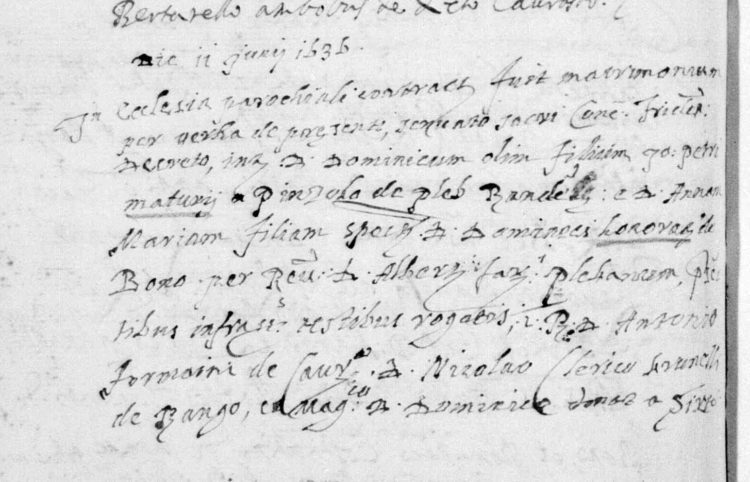

On 11 June 1636, in the parish of Santa Croce del Bleggio (Val Giudicarie Esteriore), we find the marriage of a dominus Domenico, son of the late Giovanni Pietro Maturi of Pinzolo in the parish of Rendena, and the lady Anna Maria, daughter of spectabilis dominus Domenico Onorati of Bono (a frazione of Bleggio).[xvii]

The priest who recorded the marriage did not mention a soprannome for Domenico (whose full personal name appears to have been Giovanni Domenico), but this is not unusual, as the groom had come from a different parish. Nor does the record specify he lived in the frazione of Baldino, but again this is Baldino was not a locally known village. However, in the baptismal records for the two known children of Giovanni Domenico and Anna Maria, Giovanni Domenico is referred to as ‘il Beatrice from Baldino’.[xviii] In terms of timing, it is possible Giovanni Domenico’s father, Giovanni Pietro, was the brother or cousin of the afore-mentioned Lorenzo ‘il Beatrice’ Maturi (son of Giovanni), whose name we found in legal parchments in 1605 and 1611.

The Latin term ‘spectabilis’ is an honourific, which was typically used when referring to notaries and other legal professionals. Domenico Onorati came from a long line of Onorati notaries and judges, stretching back at least to the late 1400s.[xix] Although Giovanni Domenico Maturi is not cited as being a notary in this marriage record, author Giacomo F. Maturi tells us that he was (although perhaps not yet when he married), and that both he and his son Giovanni after him obtained their law degrees at the University of Bologna.[xx] Although he does not cite any sources for this information (and I have not been able to find supporting evidence for it), children of notaries did traditionally tend to marry children of other notaries, so it is certainly feasible the Maturi-Onorati marriage was one such case.

The Maturi of Mezzana (Val di Sole)

Giovanni Domenico ‘il Beatrice’ Maturi and Anna Maria Onorati had only one son that we know of: Giovanni, born 14 June 1637. Around 1655, Giovanni married a woman named Dorotea;[xxi] the couple had at least 11 children, but at least two (including their first-born son) died in infancy. Their second-born son was Pietro Paolo Maturi, who grew up to become the founder of a new Maturi line in the village of Mezzana in Val di Sole.

Born in Baldino on 10 November 1663,[xxii] Pietro Paolo Maturi worked as a notary at least between the years 1690-1715.[xxiii] Around the year 1683, he married the noble Giovanna Calvi from Mezzana, daughter of the medical doctor Bortolo Calvi and (possibly) Elisabetta Campi.[xxiv] We know that their first two children were born in Baldino di Pinzolo: Anna Maria Elisabetta (1684) and Giovanni Bortolo Antonio (1686),[xxv] who eventually became a Catholic archbishop. We will look at the lives of both of these children a bit later.

Sometime after the birth of their second child, Pietro Paolo moved his family to his wife’s home parish, where they had at least five more children[xxvi], thus becoming the founders of a new line of Maturi in Mezzana. Author P. Remo Stenico tells us that Pietro Paolo ‘faceva la spola’ between Pinzolo and Mezzana, possibly meaning that he was continually travelling back and forth between these two places (or at least involved in legal affairs in both), which lie roughly 20 miles apart. Mezzana historian Paolo Dalla Torre says that he was the ‘Vicario of Rabbi’, but I have seen no documentation where he is referred to by this title.[xxvii]

Pietro Paolo (who had become known as Pietro Paolo Maturi ‘senior’) passed way in Mezzana on 21 February 1713.[xxviii] In 1715, we find Giovanna cited as his widow in two legal documents drafted by their son Melchiore Paolo (likely born 1690-1692),[xxix] who had followed in his father’s footsteps to become a notary.[xxx] One document, dated 4 December 1715, identifies her clearly as ‘the noble Giovanna, widow of the late Pietro Paolo Maturi, born Calvi, and mother of the (drafting) notary’.[xxxi] Descended from Melchiore Paolo and his wife Anna Giuditta Maroffer,[xxxii] we find at least two more generations of notaries, continuing into the early 1800s.[xxxiii]

In addition to their eldest son (Giovanni Bortolo Antonio), Pietro Paolo and Giovanna also had two other sons who became Catholic priests: Lorenzo Giuseppe Maturi,[xxxiv] who served as a priest in Mezzana until his death on 23 January 1741 (age 52), and their youngest son Antonio, who died on 8 February 1763, and the age of 62, having served as the curato for the parish of Romeno.[xxxv] We find both priests’ names in various parchments from the Mezzana archives transcribed by Ciccolini.[xxxvi]

Thus, with three sons who became priests, it would appear that their son Melchiore Paolo, the notary, was the sole patriarch destined to carry on Maturi surname in the parish of Mezzana, and all subsequent Maturi born in Mezzana are ultimately descended from him.

Anna Maria Elisabetta Maturi: Matriarch of the Borzaga of Ronzone

Born in Baldino on 19 August 1684, Anna Maria Elisabetta was the eldest child of Pietro Paolo Maturi and Giovanna Calvi. One 29 April 1708, when she was 22 years old, she married the noble Tommaso Romedio Borzaga of Cavareno in the parish church in Mezzana.[xxxvii]

Born nobility, Tommaso was not a notary, but his father Antonio was, like so many generations of Borzaga notaries before him. The Borzaga were a very old noble family presumed to have been a branch of the Lords of Tuenno, who transferred to Cavareno (parish of Sarnonico (Val di Non) sometime in the 1500s.[xxxviii] As Mezzana and Cavareno were not exactly next door to each other (about 26 miles across rugged terrain), I can only imagine the couple were matched together by their notary fathers, who probably had met each other through their professional dealings.

Whatever the circumstances, the couple lived a long life together, with Elisabetta (which is how she was most frequently known in married life)[xxxix] bearing at least 12 children, with the last one born when she was 51 years old. Both she and her husband were in their 70s when they passed away.[xl]

The main reason why I mention this couple is that, sometime before the birth of their second child in 1711, they moved their family from Cavareno to the frazione of Ronzone, about a mile to the northeast, becoming the ancestral parents of a new line of Borzaga in Ronzone. Thus, if you are descended from the Borzaga of Ronzone, you are also descended from the Maturi of Pinzolo (via Mezzana).

Point of interest: Tommaso Borzaga and Elisabetta Maturi are the 4X great-grandparents of award-winning Hollywood film director Frank L. Borzage (1894-1962), whose father was born in Ronzone.[xli]

From Outlaw to Archbishop – Father Antonio Maturi

Whenever the Maturi are mentioned in history books, one name is nearly always mentioned: Father (or ‘Brother’) Antonio Maturi, a Franciscan friar who became Archbishop of Naxos in Greece. Unfortunately, as prominent a figure as he was, so many published works contain errors about him.

Perhaps the most crucial error is in his name itself. Ausserer, who is one of the most commonly quoted historians, calls him ‘Francesco Antonio’, an error that is repeated in other books.[xlii] [xliii] Another source I found refers to him as ‘Gian Domenico’, which was actually the name of his paternal grandfather.[xliv]

Archbishop Antonio was actually Giovanni Bortolo Antonio Maturi, the first son of Pietro Paolo Maturi and his wife Giovanna Calvi. In his biographies, he is often said to be ‘of Pinzolo’, as he was born in Baldino di Pinzolo on 17 January 1686. [xlv] [xlvi] [xlvii] But, as we know, his family transferred to Mezzana when he was still in infancy. Thus, he was arguably more appropriately said to be of Mezzana, and the people of Mezzana have historically considered him to be one of their own.

There are many stories about the early years of the future archbishop, especially regarding his misbehaviour as an adolescent, and his later ‘glories’ in the military. While I am sure there is some true to these tales, I have found many inconsistencies and conflicts among the various sources I have consulted, and I get the impression some of these tales are the result of creative storytelling over the centuries.

As the story goes, the young Giovanni Bortolo Antonio Maturi had neither the intention nor the natural inclination to become a priest. In fact, his disposition was reputedly anything but pious and tranquil, as we are told he was:

…from youth a dissolute and violent type who, after he had killed a person in a fight, hunted by the police, would flee by enlisting in the army of Eugene of Savoy which at the time was fighting with the Turks in the service of the House of Austria.[xlviii]

Author Giacomo Filippo Maturi offers details about the event that lead to the alleged murder (or, more accurately, manslaughter). He says the young Bortolo used to come to visit his uncle Lorenzo in Baldino,[xlix] and during one of these visits, an argument broke out when the sheep from another property wandered onto Lorenzo’s land. The author says the shepherd from the other property had beaten Uncle Lorenzo, at which point Bortolo stepped in to defend him. According to this version of the tale, the shepherd hit his head on a stone and died.

Of course, this version of the story leads us to believe that the young Bortolo was simply defending his uncle, and that he was therefore virtuous and without blame.

Writing in 1986, however, historian Pizzini sees the future archbishop from an entirely different angle, saying:

‘…the young Bartolomeo, certainly of above-average build, had led a rather messy, cheeky, and even quarrelsome life, which sometimes led him to get drunk and start a fight, often armed with an arquebus [a kind of gun].’ [l]

Which of these perspectives is the more accurate, I cannot say. Whatever the truth is, most historians seem to agree that, rather than face criminal charges of murder or manslaughter, the adolescent fled Val Rendena, and sought sanctuary with the Reformed Franciscan Friars at Campo Maggiore in Vigo Lomaso (Val Giudicarie). [li] [lii]

The story continues that the Prince-Bishop of Trento (Johann Michael Graf von Spaur) had issued a ban against the young offender, forbidding him to remain or enter the principality of Trento (i.e., Trentino) on pain of death.[liii] Although the young Bortolo was safe within the walls of the Franciscan convent, he was now effectively imprisoned, as he could not return home without the threat of capture by the Prince-Bishop’s men. For this reason, we are told, he fled the province altogether, to enlist in the army of Prince Eugene of Savoy.

This is where the dates and sequence of events get a bit messy. The main issue is that none of these authors tell us when the alleged murder took place, how long he spent at the monastery, or when the Prince-Bishop imposed the ban which then triggered Bortolo’s decision to flee.

Military Service Under Prince Eugene Savoy

Giacomo F. Maturi suggests that Bortolo joined up with Savoy in the year 1704, when the young man would have been 18 years old.[liv] However, Savoy’s movements during this period (which was during the so-called War of Spanish Succession) are well-documented, and he would have been in France in that year.[lv] If the young Bortolo was facing a possible death sentence, I cannot imagine he would have taken the risk of travelling a great distance to get out of the province and find safety. Thus, from a practical level, I feel it seems more likely that he joined up with Savoy when the military leader was already inside or near the borders of the province of Trento, such as during or after the Battle of Carpi, in the summer of 1701.[lvi] This means the lad would have been only 15 years old, which again puts another spin on the bigger story.

There is one piece of evidence (albeit, again with conflicting information), which seems to indicate this earlier date of 1701 may indeed be more accurate. In a short but most interesting article by Aldo Alberti published in 1956,[lvii] we find a letter written by Prince Eugene himself on 31 July 1702, when he was staying in Borgoforte in the province of Mantova (Mantua) in Lombardia, just one month before the Battle of Luzzara.

This letter, addressed to Prince-Bishop Spaur, is regarding one Giovanni Domenico Maturi [sic], who was among the men serving Savoy, who had come to Savoy requesting a ‘salvacondotto’, which was a document giving him the right of safe passage, so he could travel back to his home (presumably Mezzana). Apparently Maturi had told Savoy about the ban against him, but Savoy believed him to be a trustworthy man, so he granted him the requested pass.

In the letter, we learn that the Prince-Bishop had gotten wind of the fact that Savoy had granted this ‘passport’ to Maturi, and he was not at all amused. Apparently, he wrote a stern letter to Savoy on 26 June 1702, expressing his displeasure over the fact that Savoy had simply disregarded the ban he had imposed.

The July letter is Savoy’s reply. What I find most amusing about this letter is how Savoy’s words are ostensibly deferential to the Bishop but, in effect, he is kind of telling him off. While telling the Bishop that he respects and honours his decisions, but the same token he (Savoy) doesn’t just easily issue passports to men of bad character. In other words (or at least this is how I interpret it), he is telling the Bishop that Maturi is a good lad, and he should lighten up about him.

I cannot explain why the letter says ‘Giovanni Domenico’ rather than Bortolo’s true name. I had wondered whether this letter was talking about a different Maturi, but how many Maturi men would have been banned by the Prince-Bishop in this era? And how many of those men would also have been in the service of Prince Eugene? Curiously, Giovanni Domenico was the name of Bortolo’s paternal grandfather. Surely, if any of this story is true, then this letter must be referring to the future archbishop. Perhaps the young man was using an alias, or perhaps Savoy or the Bishop had written the name down incorrectly. Or, of course, perhaps the author of the article simply made an error in transcription.

If this letter is indeed discussing the future archbishop, we can assume he wouldn’t just have shown up on Savoy’s doorstep in 1702 and had immediately been granted a pass to visit home. Thus, the year 1701 that I suggested above seems more likely. Although the young man appears to have visited his home in 1702, he did not remain there, as the ban against him had not yet been lifted. Rather, he seems to have returned to fight alongside Savoy, at least for a few more years.

There are many contradictory accounts of the young Maturi’s military activities. One author says, ‘Antonio Maturi reached high rank and participated in the battle of Belgrade against the Turks in 1712.’[lviii] However, this is glaringly wrong, as the Battle of Belgrade took place in 1717. In another article, the same author says Antonio ‘Bortolo’ Maturi served between 1704-1710, quickly ‘climbed the steps of a military career from a simple soldier to becoming a close collaborator (apparently a ‘secretary’) of the legendary leader Prince Eugene of Savoy’.[lix] Another author tells us ‘his zeal and intelligence immediately earned him the esteem and the loyalty of the Prince (Savoy), who named him his secretary’.[lx]

I disagree with the estimated dates above. Based on everything I have found so far, I believe the young Maturi was serving under Savoy between 1701-1706 or early 1707 (roughly age 15-21), as we know from other references that had already left the military life and returned to Mezzana by 1707. If I had to guess, I would theorise he stayed with Savoy through his victory over the French in the Siege of Turin (Summer 1706) but had already returned home before Savoy moved on to his next campaign in Toulon (August 1707).

Working as a Notary, Taking Up the Religious Life

Bortolo’s good conduct and service to Prince Eugene apparently had won him the forgiveness of Prince-Bishop Spaur, who cancelled the ban and criminal charges that had been put against the young man. Now living with his family in Mezzana, the Prince-Bishop even licensed him as a notary in 1707,[lxi] enabling him to take up the same profession of his father. In his list of notaries, P. Remo Stenico says there are fragments of documents between from 1707-1710, which were drafted in Mezzana by ‘Bartolomeo Antonio Maturi’.[lxii]

His work as a notary would be short-lived, however, as he is said to have had some kind of ‘spiritual awakening’ or personal crisis, which led to him deciding to take up a religious life. Now 24 years old, he donned the robes of a Franciscan friar in Cles on 25 June 1710, choosing ‘Antonio’ as his new name. Then, after completing rigorous theological studies in Rome, he took his solemn vows on either 6 or 11 June 1716,[lxiii] [lxiv] and then went on to celebrate his first Mass later that same month, in his home parish of Mezzana.

Life and Death Abroad

Perhaps due to his experiences fighting against the Turks, the young priest immediately expressed his desire to become a missionary in the Turkey and Greece. That same year, Father Antonio (along with Father Nicolò Widman of Coredo) was sent to Constantinople (present-day Istanbul).[lxv] Biographer Pizzini tells a that, before the young priest left for Turkey, he went to Vienna to meet up with his former military commander, Prince Eugene, who welcomed him most festively, and provided him with a pass of safe conduct to facilitate his journey and, as a personal gift, gave him 1,000 florins to pay for the cost of many Masses. Pizzini also says that Emperor Carlo IV wrote a letter of recommendation to the Papal Legate, asking him to keep Father Antonio in mind for the appointment to the then vacant Vicariate of Smyrna, (Smirne).[lxvi]

He was renowned as having a natural talent for learning languages. In addition to his native Italian, he not only understood Latin, French and German, but also Turkish, Arabic and Greek. Apparently, he had already become proficient enough to preach in Greek after having lived only six months on the Isle of Scio (Chios).[lxvii]

Although the precise dates differ according to source, we know with certainty that Father Antonio went on to become the Vicar Apostolic and Bishop-elect of Smirne (Turkey) in the spring of 1722, then becoming the Bishop of Syros (Greece) in May 1731 (consecrated the following year). In 1733, he was elevated to the rank of Archbishop of Naxos and Primate of the Greek Archipelago of the Cyclades, but with great regret, he was forced to resign, due to problems with increasingly poor health. [lxviii]

Pizzini tells us that we have many letters written by Father Antonio to his brothers and his nephew, wherein he describes his ongoing ordeal with his health, and expresses his deep remorse for abandoning his homeland, and his deep longing to return.[lxix] Sadly, he was not granted permission to return to Trentino, but was instead given the appointment as Apostolic Delegate in Syros. Poignantly, the author narrates:

He was hopelessly exhausted, and when he finally received the longed-for leave to return to Italy in 1749, he was no longer able to go, as he was being kept in bed “by two gangrenous sores on his leg that had been tormenting him for time, for which he was struck by apoplexy and died on 16 April 1751”. And over there, on the distant island of Syros, he rests. [lxx] [lxxi]

The Question of Nobility, and the Maturi Stemma (Coat-of-Arms)

Historian Paolo Dalla Torre tells us that, in the urbario of the Maturi of Mezzana (which seems to have been written in the mid-18th century), the father of Pietro Paolo Maturi is referred to as ‘Giovanni Maturi, a nobleman of Baldino’.[lxxii] In my own research, I have seen the Pietro Paolo Maturi ‘junior’ (grandson of the other Pietro Paolo), who was Doctor of Law, referred to as ‘clarissimi’, which is generally a term reserved for imperial nobility.[lxxiii]

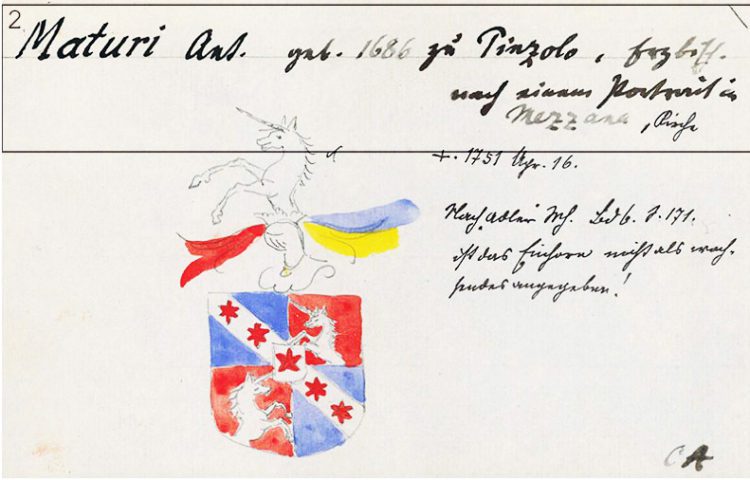

However, other authors note that the Maturi do not appear to have been one of the noble families of the Giudicarie,[lxxiv] and I have not found any reference to the Maturi having been ennobled at any point in time. Nonetheless, some members of the Mezzana family adopted the coat-of-arms that had been granted to the aforementioned Archbishop Antonio Maturi (shown below),[lxxv] which is also depicted in the church in Mezzana.

In the Tiroler Landesmuseen in Innsbruck, we also find a sketch of this stemma from the church in Mezzana, with notes saying it belonged to Archbishop Antonio Maturi, who was born in Pinzolo in 1686, and died on 16 April 1751. [lxxvi]

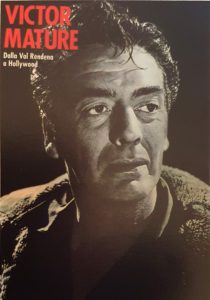

Hollywood Actor Victor Mature

Arguably, especially amongst those who live outside Trentino, the most famous Maturi personality is the Hollywood actor Victor Mature.

Born in Louisville, Kentucky, USA on 29 January 1913, Victor John Mature was the son of knife-grinder Marcellino Gelindo Maturi (born 18 June 1877) of Pinzolo, [lxxvii] [lxxviii] and American-born Clara Ackley. Victor’s father Marcellino came from the ‘Cilleno’ branch of the Maturi of Pinzolo, a soprannome adopted in the mid-1700s by the descendants of Antonio Maturi (of the ‘Donà line) and his wife Maria Maffei. Ultimately, this line can be traced back to one Simone Maturi, who was born in Pinzolo around 1570. Even by that date, this was already separate line from the previously discussed ‘il Beatrice’ Maturi who lived in Baldino.

Victor’s acting career spanned more than four decades, and he appeared in over 50 Hollywood movies between 1939-1984. Known for his rugged physique,[lxxix] Victor was frequently cast in roles of the ‘strong’ or ‘tough guy’. He starred in many famous historical and biblical films including Samson and Delilah, Androcles and the Lion, The Robe, The Egyptian, and Hannibal.[lxxx]

He passed away from leukaemia at the age of 86 on 9 August 1999. There is a star for him on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[lxxxi]

The Maturi of Cavizzana And Caldes

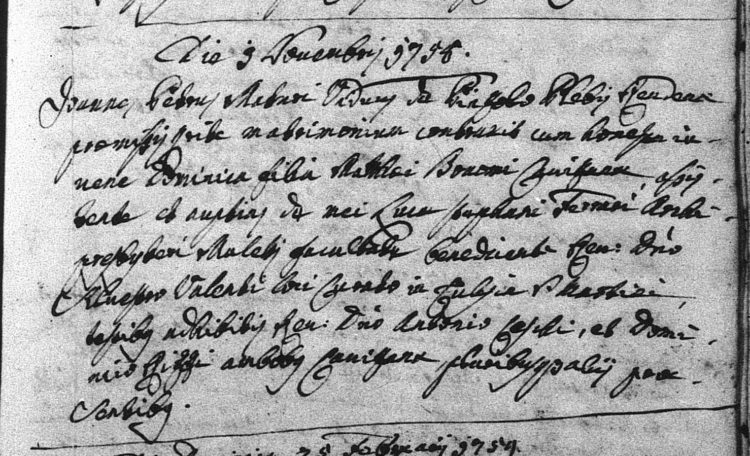

In the mid-18th century, a new branch of Maturi started Cavizzana (Val di Sole) when a widowed Giovanni Pietro Maturi of the ‘Barcarol’ branch in of Pinzolo[lxxxii] married Domenica Bonomi (daughter of Matteo) of Cavizzana on 1 November 1758.[lxxxiii]

Rather than staying in Pinzolo, Giovanni Pietro chose to settle in Domenica’s home village of Cavizzana, where they had at least three sons and three daughters. In the Cavizzana record, he is frequently referred to as Pietro, rather than Giovanni Pietro.

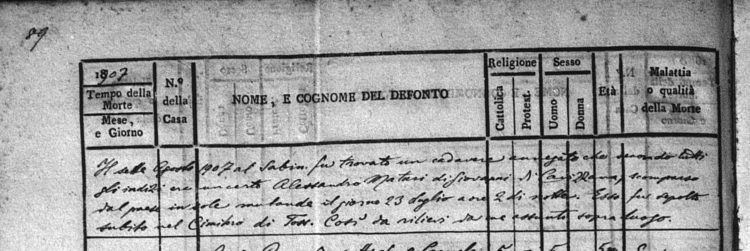

Their son Pietro Giuseppe (known mostly just as Giuseppe) was born in Cavizzana on 19 December 1763, and married the noble Lucia Bertoldi of Samoclevo on 24 April 1787.[lxxxiv] Pietro Giuseppe and Lucia are the ancestors of all the Maturi of Cavizzana. The surname it did not expand significantly there, however, due to factors such as a high percentage of daughters compared to sons, a viral epidemic (called ‘Rioma’) that took the lives of many young children in the 1820s, and the untimely death of a young, unmarried man who drowned at age 21.[lxxxv] Moreover, at least two Maturi men from this line permanently immigrated to Minnesota in the US at the end of the 19th century.[lxxxvi]

ABOVE: Death record dated 7 August 1907 for an Alessandro Maturi of Cavizzana, son Giovanni Francesco Maturi and Violante Rizzi. The record says the young man, dressed only in his underwear, went missing around 2 AM on the night of 23 July 1907, and his drowned corpse was found downstream in the Torrente Noce in Sabino on 7 August 1907 (his 22nd birthday) where witnesses identified him. He was buried immediately in the cemetery in Toss, which does make us wonder if his parents had seen their son’s body before it was buried. There certainly seems to be a backstory here we will probably never know.

Another factor that limited the growth of the surname in Cavizzana is the fact that the youngest son of Giovanni Pietro Maturi and Domenica Bonomi – Giovanni Battista Maturi – did not remain in Cavizzana. On 30 June 1788, at the age of 21,[lxxxvii] Giovanni Battista married Maria Margherita Bertoldi of Samoclevo, the younger sister of his brother’s wife Lucia.[lxxxviii] After Maria Margherita gave birth to five daughters in Cavizzana, we find their sixth child (another daughter) was born in Caldes, after which they permanently settled in Caldes, where all their later children were born. Altogether, Maria Margherita would give birth to 11 children – 8 of them daughters – the last of whom had died in the womb, causing a miscarriage that ultimately led to Maria Margherita’s death at age 38.[lxxxix] Of their three sons, two died soon after birth, and the youngest was killed at age 25 while serving in the military in Piemonte.[xc]

It would have seemed that the Maturi of Caldes were destined to die out completely at this point, but the widowed Giovanni Battista remarried the widowed Anna Maria Leonardi of Tuenno, with whom he had one more daughter and two sons. Luckily, both of these sons were healthy and grew up to have families of their own.

Owing to an enormous number of infant deaths, the line descended from the elder son, Pietro Battista Michele (born 1 June 1809), died out before the beginning of the 20th century, but the descendants of their younger son, Giovanni Matteo Maturi (born 28 August 1813) appear to be continuing in Caldes to this day.[xci]

The Maturi Today

The Nati in Trentino website shows there were 527 births with the surname Maturi (sometimes spelled Matturi) recorded in Trentino between the years 1815-1923. Of these, 379 were registered in Pinzolo/Giustino, 27 in Mezzana, 28 in Cavizzana, and 67 in Caldes.[xcii] Although I have not traced the remaining 26 that are scattered around various places, I am quite confident that they will all link back to one of the four lines we have explored in this article, with all lines ultimately leading back to Pinzolo.

To give you an idea of the prevailing diversity of the Maturi in their native Pinzolo, you find no fewer than ten Maturi soprannomi there by the beginning of the 20th century: Ciarin, Cilleno, Colcort, Donà, Donadin, Grapot, Pladon, Paparot, Simonella, and Toson. Many older soprannomi (including the afore-mentioned Barcarol and Beatrice lines) had either gone extinct or evolved into new soprannomi by then. Pinzolo researcher James R Caola tells me that all of present-day Maturi branches in Pinzolo are offshoots of the Donà line, which dates back at least to the mid-1700s.

Like many Trentino surnames, its numbers have decreased in Trentino since the beginning of the 20th century, owing mostly to immigration. A relatively uncommon surname, there are reportedly only 166 Maturi families living in Italy today, about one-third of which live in Trentino. Beyond Trentino, it can also be found in Lazio (especially around Rome), and in Campania to the south, with smaller numbers in other regions. [xciii]

In today’s Trentino, the Maturi surname it is still found in the largest concentration (87%) in Val Rendena (Pinzolo, Giustino, Carisolo), with only one Maturi family currently living in Mezzana, one in Cavizzana, and one in Caldes. The fact that the Maturi continue to flourish in such numbers in the Pinzolo area, even after more than half a millennium, is a clear reflection of their ancient Rendena origins.

Closing Thoughts

This article started out as a short entry for my ongoing book project Guide to Trentino Surnames for Genealogists and Family Historians. As it evolved into a much longer piece than I had originally intended, it will become part of a different book I am compiling on more in-depth surname studies. As these projects will take several more years to complete, I am offering this article as a PDF eBook, available for a small fee on my digital shop.

Want to keep this article to read offline? You can purchase it as a 25-page printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, charts, footnotes and resource list.

Price: $3.00 USD.

Available in Letter size or A4 size.

CLICK HERE to buy this article in the ‘Digital Shop’, where you can also browse for other genealogy articles.

I hope you enjoyed this brief study of the origins and evolution of the Maturi surname, from Val Rendena to Val di Sole and beyond. If you have Maturi ancestors, I also hope it has helped to enrich your understanding of your personal family history and cultural heritage.

If you have any comments or questions, or if you are seeking help researching your Trentino family, please feel free to contact me at https://trentinogenealogy.com/contact.

Until next time!

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

27 March 2023

P.S. I am currently taking client bookings for JULY 2023 and beyond. If you would like to book a time to discuss having me do research for you, I invite you to read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, we can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://trentinogenealogy.com/my-tree/

NOTES

[i] Both maps from ANZILOTTI, Giulia Mastrelli. 2003. Toponomastica Trentina: i nomi delle località abitate. Trento: Provincia autonomia di Trento, Servizio Benni librari e archistici. Colour highlights are my own.

[ii] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino. Trento: Società Iniziative Editoriali (S.R.L.), page 218-219.

[iii] Bertoluzza says there is a document from 1319 wherein a ‘Gianesio, son of the late Maturino of Rovereto’ is mentioned, but he gives no details about the source. Note that 1319 is in an era before surnames were in use.

[iv] MATURI, Giacomo Filippo. 1983. I Maturi di Pinzolo. Independent study by the author. On page 3 he comments that ‘Madur’ is a dialect form.

[v] MATURI, Carla. 2018. ‘Maturi & Mature da Pinzolo. Judicaria, n. 98 (August 2018), page 115. Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria.

[vi] MATURI, Giacomo Filippo. 1983. I Maturi di Pinzolo, page 1. He does not give the precise date, saying only ‘the 1400s’.

[vii] Provincia Autonoma di Trento. ‘Promessa di pagamento, 20 October 1456, Castel Cles’. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1605715. Accessed 4 March 2023.

[viii] Tione parish records, marriages, volume 1. The precise date is missing, but it comes a few records after August 1584.

[ix] TOVAZZI, Giangrisostomo, OFM. 2006. Biblioteca Tirolese: o sia Memorie Istoriche degli Scrittori della Contea del Tirolo. Curated P. Remo Stenico and Italo Franceschini (originally written in 1806). Trento: Fondazione Biblioteca San Bernardino, Comune di Volano, page 695, Articolo 866.

[x] STENICO, P. Remo. 2000. Sacerdoti della Diocesi di Trento dalla sua Esistenza Fino all’Anno 2000. Indice Onomastico, page 274.

[xi] Provincia Autonoma di Trento. ‘Compromesso tra Fisto, Ches e la comunità di Bocenago, 2 August 1605, Campiglio’. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1703936. Accessed 4 March 2023.

[xii] Provincia Autonoma di Trento. ‘Contenitore 4, Quietanza, 17 October 1611, Stenico’. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/2363138. Accessed 4 March 2023.

[xiii] Provincia Autonoma di Trento. ‘Contenitore 1, Lodo Arbitrale, 17 October 1611, Stenico’. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1218309. Accessed 4 March 2023.

[xiv] Giovanni (born 14 June 1637), and Francesca (born 27 September 1639), son and daughter of Giovanni Domenico Maturi, called ‘il Beatrice’ of Baldino, and his wife Anna Maria Onorati. Based on research by James R. Caola.

[xv] Bartolomeo, born 9 January 1639, son of Bartolomeo Maturi, called ‘Donatis’, and his wife Maddalena. Based on research by James R. Caola. This most likely evolved into the later soprannome ‘Donà’ and/or Donadin.

[xvi] MATURI, Giacomo Filippo. 2003. ‘Arcivescovo Antonio Maturi 1686-1751.’ From Collana “Persone ed avvenimenti” del Comune di Pinzolo 2003. Accessed 10 March 2023 from https://www.campanedipinzolo.it/arcivescovo-antonio-maturi-1686-1751-di-giacomo-f-maturi/ .

[xvii] Santa Croce parish records, marriages, volume 1, no page number.

[xviii] The couple had a son named Giovanni (born 14 June 1637) and a daughter named Francesca (born 27 September 1638). Information via James R. Caola, using the Giustino parish records.

[xix] This is based on my own extensive research of the Santa Croce parish records and pergamene.

[xx] MATURI, Giacomo Filippo. 2003. ‘Arcivescovo Antonio Maturi 1686-1751.’

[xxi] Thus far, neither I nor my colleagues have found this marriage record or identified who Dorotea was.

[xxii] Date via researcher James R. Caola, using the Pinzolo parish registers.

[xxiii] STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 232.

[xxiv] PIZZINI, Pasquale. 1986. ‘Mons. Antonio Maturi da Pinzolo Primate dell’archipelago greco’. Judicaria, n. 2 (May-August 1986), page 27-29. Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. On page 27, the author makes a reference to ‘the inherited assets of both the father Bortolo and the mother Elisabetta de Campi’. As Campi is a Mezzana surname, I am presuming he is talking about Giovanna’s parents, but the wording is somewhat ambiguous, and he cites no source for the information.

[xxv] Names and dates of birth from Pinzolo parish registers, baptisms, volume 1, no page numbers.

[xxvi] Pizzini lists 7 children in total, but James R. Caola records another that Pizzini does not mention.

[xxvii] DALLA TORRE, Paolo. 2005. Mezzana e le sue Frazioni: Roncio, Menas, Ortisé e Marilleva. Storia di cinque comunità. Malé: Tipolitografica Andreis for Comune di Mezzana, page 319.

[xxviii] Date via researcher James R. Caola.

[xxix] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1936. Inventari e Regesti degli Archivi Parrocchiali della Val di Sole. Volume 1: La Pieve di Ossana. Trento: Libreria Moderna Editrice A. Ardesi, page 170, carta 519. ‘Giovanna, widow of the late Dr Pietro Paolo Maturi, and mother of the drafting notary’ cited in a document dated 25 August 1715.

[xxx] STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 232. ‘Melchiore Paolo, notary of Mezzana, son of the notary Pietro Paolo Maturi.’ The author says he was active in his profession until at least 1746.

[xxxi] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1936. Inventari e Regesti degli Archivi Parrocchiali della Val di Sole. Volume 1: La Pieve di Ossana. Trento: Libreria Moderna Editrice A. Ardesi, page 171, carta 523.

[xxxii] Anna Giuditta was from Albes in Bressanone, present-day South Tyrol. The couple married in Mezzana on 25 November 1716. Info via researcher James R. Caola using the Mezzana parish records.

[xxxiii] Melchiore Paolo’s son Pietro Paolo ‘junior’ (active between 1745-1790), and his grandson (son of Pietro Paolo Junior), Giovanni Antonio, active at least between 1762-1809. STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 232.

[xxxiv] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1936. Inventari e Regesti degli Archivi Parrocchiali della Val di Sole. Volume 1: La Pieve di Ossana. Trento: Libreria Moderna Editrice A. Ardesi, page 170, carta 518. In a document drafted in the house of notary Melchiore Paolo Maturi in Mezzana, dated 25 August 1715, we find ‘Witness, don Lorenzo Maturi, priest, brother of the drafting notary’.

[xxxv] STENICO, P. Remo. 2000. Sacerdoti della Diocesi di Trento dalla sua Esistenza Fino all’Anno 2000. Indice Onomastico, page 274. Simone Weber confirms Antonio was the curate of Romeno until his death, but his death record does not appear in the register for Romeno (there appears to be a 4-month gap, possibly because there was nobody to record them).

[xxxvi] One example, dated 22 September 1726, says ‘the Reverends Lorenzo and Antonio Maturi, brothers, priests.’ CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1936. Inventari e Regesti degli Archivi Parrocchiali della Val di Sole. Volume 1: La Pieve di Ossana. Trento: Libreria Moderna Editrice A. Ardesi, page 173, carta 533.

[xxxvii] Date via James R. Caola.

[xxxviii] For details of the Borzaga family history, I refer you to an article I wrote IN 2022, entitled ‘The Borzaga of Cavareno. Origins, Genealogy, Famous People’. See https://trentinogenealogy.com/2022/08/borzaga-cavareno-genealogy-famous/

[xxxix] She is called ‘Elisabetta’ in the baptismal records of 9 of her 12 children, and ‘Maria Elisabetta’ in the other three. They are definitely the same woman, as the ‘Maria Elisabetta’ occur in between the others.

[xl] Elisabetta died at the age of 70 in April 1755 (the precise date is missing in the record). Sarnonico parish records, deaths, volume 2, page 346-347. Her husband died at age 73 on 15 September 1759ES. Sarnonico parish records, deaths, volume 2, page 372-373.

[xli] For more information about the Borzaga of Ronzone, I again refer you to https://trentinogenealogy.com/2022/08/borzaga-cavareno-genealogy-famous/

[xlii] AUSSERER, Carl. 1985. Le Famiglie Nobili Nelle Valli del Noce: Rapporti con i Vescovi e con i Principi Castelli, rocche e residenze nobili Organizzazione, privilegi, diritti; I Nobili rurali. Translated by Giulia Anzilotti Mastrelli from the original German work Der Adel des Nonsberges, published in 1899. Malé: Centro Studi per la Val di Sole. The author refers to him as ‘Francesco Antonio Maturi’ on page 269.

[xliii] DALLA TORRE, Paolo. 2005. Mezzana e le sue Frazioni: Roncio, Menas, Ortisé e Marilleva. Storia di cinque comunità. Malé: Tipolitografica Andreis for Comune di Mezzana. On page 319, the author quotes Ausserer’s error, calling him ‘Francesco Antonio’.

[xliv] ALBERTI, Aldo. 1956. ‘Il Principe Eugenio di Savoia ed un bandito solandro’. Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche. Year XXXV (1956), volume 1, page 85-86. He relates this information from a publication called Uomini Illustri della Val di Sole by Quirino Bezzi.

[xlv] Pinzolo parish registers, baptisms, volume 1, no page number.

[xlvi] STENICO, P. Remo. 2000. Sacerdoti della Diocesi di Trento dalla sua Esistenza Fino all’Anno 2000. Indice Onomastico, page 274. P. Remo Stenico gives a birth date of 17 January 1686.

[xlvii] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 192. The authors give both date of birth and date of death.

[xlviii] MATURI, Giacomo F. 1984. Il nostro Baldino: per un ritorno alle nostre radici, per far rivivere una tradizione che non vogliamo dimenticare. English translation by James R. Caola (2003). Expanded Italian version also published 2009 by Malè (TN): Graffite Studio.

[xlix] Lorenzo Vincenzo Maturi, younger brother of Pietro Paolo, was born 20 November 1673. Date via James R. Caola.

[l] PIZZINI, Pasquale. 1986. ‘Mons. Antonio Maturi da Pinzolo Primate dell’archipelago greco’. Judicaria, n. 2 (May-August 1986), page 27-29. Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. My translation.

[li] MATURI, Giacomo Filippo. 2003. ‘Arcivescovo Antonio Maturi 1686-1751.’ From Collana “Persone ed avvenimenti” del Comune di Pinzolo 2003. Accessed 10 March 2023 from https://www.campanedipinzolo.it/arcivescovo-antonio-maturi-1686-1751-di-giacomo-f-maturi/ .

[lii] PIZZINI, Pasquale. 1986. ‘Mons. Antonio Maturi da Pinzolo Primate dell’archipelago greco’. Judicaria, n. 2 (May-August 1986), page 27-29. Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria.

[liii] ALBERTI, Aldo. 1956. ‘Il Principe Eugenio di Savoia ed un bandito solandro’. Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche. Year XXXV (1956), volume 1, page 85-86.

[liv] MATURI, Giacomo Filippo. 2003. ‘Arcivescovo Antonio Maturi 1686-1751.’ From Collana “Persone ed avvenimenti” del Comune di Pinzolo 2003. Accessed 10 March 2023 from https://www.campanedipinzolo.it/arcivescovo-antonio-maturi-1686-1751-di-giacomo-f-maturi/ .

[lv] WIKIPEDIA. ‘Prince Eugene of Savoy.’ Retrieved 7 March 2023 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Eugene_of_Savoy.

[lvi] WIKIPEDIA. ‘Battle of Carpi’ Retrieved 14 March 2023 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Carpi.

[lvii] ALBERTI, Aldo. 1956. ‘Il Principe Eugenio di Savoia ed un bandito solandro’. Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche. Year XXXV (1956), volume 1, page 85-86.

[lviii] MATURI, Giacomo F. 2009. Il nostro Baldino: per un ritorno alle nostre radici, per far rivivere una tradizione che non vogliamo dimenticare. Malè (TN): Graffite Studio. English translation by James R. Caola.

[lix] MATURI, Giacomo Filippo. 2003. ‘Arcivescovo Antonio Maturi 1686-1751.’ From Collana “Persone ed avvenimenti” del Comune di Pinzolo 2003. Accessed 10 March 2023 from https://www.campanedipinzolo.it/arcivescovo-antonio-maturi-1686-1751-di-giacomo-f-maturi/ .

[lx] PIZZINI, Pasquale. 1986. ‘Mons. Antonio Maturi da Pinzolo Primate dell’archipelago greco’. Judicaria, n. 2 (May-August 1986), page 27-29. Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria.

[lxi] PIZZINI, Pasquale. 1986. ‘Mons. Antonio Maturi da Pinzolo Primate dell’archipelago greco’. Judicaria, n. 2 (May-August 1986), page 27-29. Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria.

[lxii] STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 232.

[lxiii] G CATHOLIC. ‘Metropolitan Archdiocese of Izmire, Turkey. The official G Catholic website says he was ordained on 6 June 1716. Accessed 16 March 2023 from http://www.gcatholic.org/dioceses/diocese/izmi0.htm?tab=bishops .

[lxiv] PIZZINI, Pasquale. 1986. ‘Mons. Antonio Maturi da Pinzolo Primate dell’archipelago greco’. Judicaria, n. 2 (May-August 1986). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria, page 27. Pizzini gives a date of 11 June 1716.

[lxv] PIZZINI, Pasquale. 1986. ‘Mons. Antonio Maturi da Pinzolo Primate dell’archipelago greco’. Judicaria, n. 2 (May-August 1986). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria, page 28.

[lxvi] PIZZINI, Pasquale. 1986. ‘Mons. Antonio Maturi da Pinzolo Primate dell’archipelago greco’. Judicaria, n. 2 (May-August 1986). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria, page 28.

[lxvii] PIZZINI, Pasquale. 1986. ‘Mons. Antonio Maturi da Pinzolo Primate dell’archipelago greco’. Judicaria, n. 2 (May-August 1986). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria, page 28.

[lxviii] The official dates given on the G Catholic website differ slightly from those given by Pasquale Pizzini and other Trentino biographers. I have also seen two different dates of his resignation, one in 1747 and another in 1749.

[lxix] Pizzini lists the recipients of these letters as 1) his brother Lorenzo (a priest, who served as parroco of Romeno), his brother Antonio (another priest, who was the curate of Mezzana), his brother Melchiore Paolo (a notary in Mezzana), and his nephew Giuseppe Antonio Borzaga, who was also a Franciscan friar known by the name ‘Cirillo’.

[lxx] PIZZINI, Pasquale. 1986. ‘Mons. Antonio Maturi da Pinzolo Primate dell’archipelago greco’. Judicaria, n. 2 (May-August 1986). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria, page 29, my translation.

[lxxi] I have seen several different dates of death for him in different sources.

[lxxii] DALLA TORRE, Paolo. 2005. Mezzana e le sue Frazioni: Roncio, Menas, Ortisé e Marilleva. Storia di cinque comunità. Malé: Tipolitografica Andreis for Comune di Mezzana, page 319.

[lxxiii] 26 March 1772, ‘Clarissimi L. L. Doctor dominus Pietor Paolo Maturi of Mezzana’ cited in the baptismal record of his granddaughter Maria Teresa Cioli in Samoclevo. Samoclevo parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 59-60.

[lxxiv] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 192.

[lxxv] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche. Stemma on page 360. Historical information on page 192.

[lxxvi] TIROLER LANDESMUSEEN. Tyrolean Coats of Arms. ‘Zambiasi’. Accessed 10 March 2023 from http://wappen.tiroler-landesmuseen.at/index34a.php?wappen_id=19231&drawer=&tr=1#next. There is a note that says the card was either made by Carl Ausserer in 1897 or comes from his collection.

[lxxvii] WIKIPEDIA. ‘Victor Mature’. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victor_Mature. Accessed 4 March 2023.

[lxxviii] Date via NATI IN TRENTINO. Provincia autonomia di Trento. Database of baptisms registered within the parishes of the Archdiocese of Trento between the years 1815-1923. https://www.natitrentino.mondotrentino.net/.

[lxxix] MATURI, Carla. 2018. ‘Maturi & Mature da Pinzolo. Judicaria, n. 98 (August 2018), page 115-116. Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. The author notes that both men were known for their strong build, and she comments on Victor’s Rendese features.

[lxxx] WIKIPEDIA. ‘Victor Mature’. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victor_Mature. Accessed 4 March 2023.

[lxxxi] WIKIPEDIA. ‘Victor Mature’. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victor_Mature. Accessed 4 March 2023.

[lxxxii] Giovanni Pietro was born in Pinzolo on 1 April 1729; he was the son of Pietro Maturi of Pinzolo and Cattarina Nicolini of Strembo. Info via James R. Caola.

[lxxxiii] Malé parish records, marriages, volume 7, page 85. His first wife was Giacoma Domenica Polli (married 12 September 1754), who most likely died shortly after having given birth to their only child, a son named Giovanni, on 20 June 1757. Unfortunately, we can only conjecture this, as all the death records prior to 1778 were destroyed in a fire in 1913. Info via James R. Caola.

[lxxxiv] Samoclevo parish records, marriages, volume 1, no page number. Lucia was born 07 December 1760; Samoclevo parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 33-34.

[lxxxv] Information gleaned from the Cavizzana death records, volume 1.

[lxxxvi] Giuseppe Raimondo (1869-1943) and his younger brother Diomiro (1878-1965), sons of Giovanni Francesco Maturi and Violante Rizzi, are recorded as having died in Chisholm, St. Louis County in Minnesota. Their graves also appear on the Find-A-Grave website.

[lxxxvii] Giovanni Battista was born in Cavizzana on 4 August 1766. Cavizzana parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 16.

[lxxxviii] Samoclevo parish records, marriages, volume 1, no page number. Maria Margherita was born 07 November 1767; Samoclevo parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 49-50.

[lxxxix] The child was aborted on 11 November 1805, and Maria Margherita died a week later on 8 November. Caldes parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number. The Latin is archaic, but it seems that the mother may have gone into labour early, owing to pleurisy she had developed either from this or an earlier pregnancy.

[xc] Pietro Giuseppe Maturi (born 18 September 1803) died in Val Baiarda in Piemonte on 6 August 1829. Caldes parish records, deaths, volume 2, page 8-9.

[xci] Although the parish register has not be digitised beyond the year 1923, we find marriages and deaths through the 1950s recorded in the indices of the Caldes registers.

[xcii] NATI IN TRENTINO. Provincia autonomia di Trento. Database of baptisms registered within the parishes of the Archdiocese of Trento between the years 1815-1923. https://www.natitrentino.mondotrentino.net/.

[xciii] COGNOMIX. ‘Maturi’. Mappe dei cognomi italiani. https://www.cognomix.it/mappe-dei-cognomi-italiani/MATURI. Accessed 4 March 2023.