Genealogist Lynn Serafinn and her grandson, Percy, celebrate Il Giorno di Morti (The Day of the Dead), and discover the power of filò – family storytelling.

Genealogist Lynn Serafinn and her grandson, Percy, celebrate Il Giorno di Morti (The Day of the Dead), and discover the power of filò – family storytelling.

Like many, if not most, people of Trentini descent, I was raised Roman Catholic (although, in my case, I probably owe my religious education more to my Irish mother than my Trentino-born father). For Catholics, the first two days of November are special holy days.

November 1st is ‘All Saints Day’, the purpose of which is to honour the memory of all the saints in Heaven, even those about whom we might never have heard. The name of our modern holiday ‘Halloween’, which falls on October 31st, was derived from the term ‘All Hallows Eve’, i.e. the evening before the day on which all ‘hallowed’ spirits are honoured.

November 2nd is ‘All Souls Day’, the purpose of which is to pray for the souls of all those who have left this world. In Italy, it is called Il Giorno di Morti – the Day of the Dead. While English-speaking people may not be familiar with the Italian term, many may have heard of Dia de los Muertos, which is the celebration of the Day of the Dead amongst Mexican Catholics.

As I write this article, it is November 2nd – the Day of the Dead. As a genealogist, sometimes it seems like every day is the Day of the Dead, as I am constantly researching and thinking about those who walked this planet before us. But for me, the transition from the month of October to November always has special significance, because my father (who passed away in 2001) was born on Halloween – October 31st, 1919 – in the parish of Santa Croce del Bleggio, in Trentino. His birth name was ‘Romeo Fedele Serafini’, but it he changed it to ‘Ralph Serafinn’ in the 1930s, after the family emigrated to the United States.

This year, on my dad’s birthday, I thought about posting some photos or stories about my dad on Facebook, but work got in the way and it felt like I had lost the moment. But then, last night, something unexpected happened: my 11-year-old grandson, Percy, called me on the phone. His mom (my daughter, Vrinda) had come up with the idea to celebrate Dia de los Muertos by remembering the family Percy never got the chance to meet. As part of this, she told him to call me and ask me to tell him some stories about my parents.

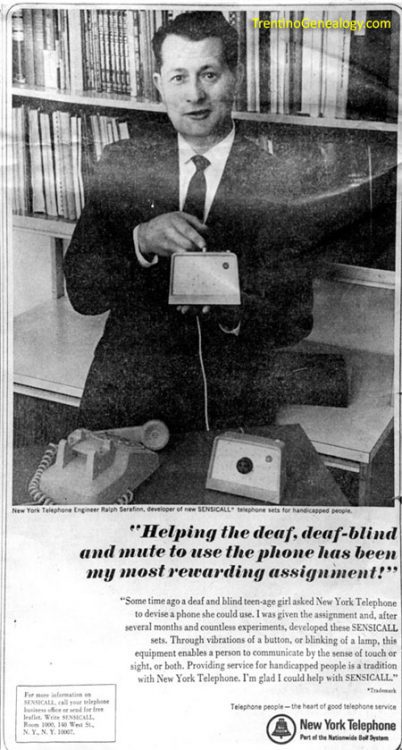

Ralph Serafinn – Inventor of the First Telephone for the Deaf

I asked Percy what kind of stories he wanted to hear. At first, he said, ‘Anything,’ but then he said his mom had told him my dad had invented the first telephone device for the deaf, and he wanted me to tell him more. I told him how my father was an electrical engineer for the New York Bell phone company. In 1965, the company gave him the assignment to come up with a device that would enable the deaf and deaf-blind to use the telephone. I told Percy how my dad worked in our basement for many months, experimenting with different ideas. He created two different devices – one using a small, red flashing light to communicate in Morse code (for deaf people who could see), and another that used a sensitive, hand-held buzzer that could transmit the code through vibrations (for the deaf-blind). I explained that there was no such thing as home computers in those days, so these were actually cutting-edge technologies even though they might look very primitive to us today.

I told Percy how my dad used to invite me – then 10 years old – to help him with his experiments. He would send me into another room with one of his beta models, and I would report back to him how many lights I saw or buzzes I felt. As the devices became more precise, I had to tell him whether the signals were long or short (as in Morse code). I explained how my father also invented a system that made the lights in the house flash on and off when a call came in, so the deaf and hard-of-hearing knew they had a phone call.

I told Percy how a newspaper came and took photos of my dad working, and even took one of me working alongside him (sadly, those photos have been lost with time). I told him how the story of my dad’s invention – dubbed the ‘Sensicall’ – was covered in newspapers all over the United States, and how we received letters from people all over the world (I remember one very beautiful one from South America) profusely thanking my father for inventing this device. Those days are some of my fondest memories of my dad, and it was such a privilege to share the story with my grandson.

Then Percy made a very astute – and beautiful – comment. He said, ‘You know how you said they didn’t have home computers back then? Well, you might say that without my great-grandfather’s invention, there might not BE any home computers today. It’s like, his invention is the thing that made everything else happen.’

‘Yes,’ I agreed. ‘It’s like building a staircase to go from one level to another. Each step is important. You can’t just leap from the ground floor to the second floor. There’s no telling how different the world would be if you took out even one step.’

From this, Percy asked questions about my dad during World War 2. I told him how my dad had fought in Japan, and was on a ship on the Pacific, less than 100 miles from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, when the US dropped the atomic bomb on those cities. We talked about how my father died at the age of 81 from a rare blood disorder called myelodysplasia, which has been linked to exposure to high amounts of radiation. We even talked about my father’s (sometimes wacky) OCD – a condition both my daughter and Percy inherited (at least in part) from my dad.

Escape from Siberia in World War 1

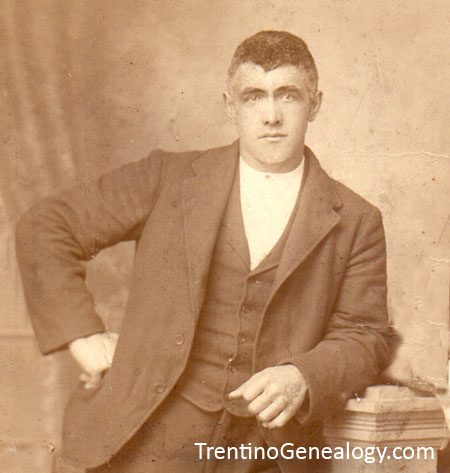

Percy then asked me to tell him stories about my grandfather – Luigi Pietro Serafini, who was born in the same village of Duvredo in 1888.

Percy remember hearing that Luigi had fought in World War 1, but didn’t know much else. I didn’t want to go into all the politics of Trentino being part of the Austro-Hungarian empire (I’ll save that for another discussion), as I thought it would take us off the track of talking about my grandfather. So, I told Percy how my grandfather was sent to fight in Russia, and how he and thousands of others were captured by the Russian army and sent to Siberia, where they were prisoners of war for about two years.

Percy was curious to know what it was like in the prison. He asked me, ‘Did they feed the prisoners? Was it like prison food?’ I told him, yes, they fed them, but it was probably not very nutritious food. I explained that many men died from illness, lack of nutrition and poor sanitation.

‘Didn’t you tell me once that he escaped from the prison camp?’ Percy asked.

I acknowledged this was true. Percy then asked how my grandfather managed to get out.

I told him, ‘Well, actually, there are three different versions of that story, and I’m not sure which is true.’

‘Why not?’ he queried.

‘Because people tend to elaborate when they tell family stories. They’re not necessarily lying, but they will often make up things to fill in forgotten details, or just to make the story more exciting. Would you like to hear all the different versions, so you can decide?’ I asked him.

‘Yes, please!’

‘Well,’ I said, ‘story number one, which my father told me, is that my grandfather was so ill with some disease, he fell unconscious. The Russians thought he was dead (or as good as), so they tossed him into a mass grave with a lot of other dead bodies. Then, something happened (my father never said what), which caused the Russians to leave in a hurry. When my grandfather regained consciousness, he found himself surrounded by dead bodies! At first, he felt panic; but eventually he realised his captors were gone, and he was free to go. Then, he got up and walked home – many hundreds of miles, in tattered clothes and in poor health – all the away from Siberia to Trentino.

‘Story number two is one I heard from my (male) cousins, who said they had also heard it from my father. It’s similar to the first story, except in this version, my grandfather supposedly “faked his own death” so the Russians would toss him outside the camp into the place where they kept the dead bodies. He lay there until dark, and when the guards weren’t looking, he got up and ran as fast as he could until he knew he wasn’t being followed. Then, he walked home.

‘Story number three is less dramatic, but is possibly closer to the truth,’ I said. ‘It’s something I read in a book specifically about the prisoners of war in Siberia in World War 1. In 1917 there was a big revolution in Russia. When that happened, the whole Russian government collapsed, including the army. There was no more money to feed the prisoners, or to pay the soldiers who guarded the prisons. So, the prison guards opened the gates and basically told the prisoners they were on their own now. Many thousands left and made their way home on foot. Some, who were either too ill or too afraid to leave, stayed behind and didn’t go home until the Red Cross came to help almost a year later. My grandfather was one of the men who left.’

Percy asked me, ‘If you were in that situation, would you have left, or would you have waited for the Red Cross to come?’

‘Oh, I would have left and taken my chances,’ I said.

‘Really?’

‘Definitely. After spending so much time in prison, I’d just want to get out of there, and I’d worry about the details later.’

Percy seemed to like my reply.

‘Which story do you think is true?’ I asked him.

‘I like the one about faking his own death!’ he chimed enthusiastically.

That figures, I thought to myself. That’s the version my dad told my male cousins, when the eldest was about Percy’s age. I guess it’s the kind of story boys would like.

‘Yes, it’s very dramatic,’ I acknowledged. ‘But somehow I don’t think the Russian soldiers would have been so easily fooled.’

Percy quickly agreed, and immediately adopted version number 1 as his own.

‘I’m going to tell my friends that my great-great-grandfather escaped from prison because he was tossed into a stack of dead bodies by the Russians,’ he said with great satisfaction.

A FOURTH VERSION: Something I only remembered after my call with Percy is that my father’s sister, Fiorina, wrote a story about her father’s escape from Siberia, in which she says the Russian guards simply opened the gates one day and let them all go. She doesn’t offer an explanation for why, but I am certain it is linked to the timing of the Russian revolution. Fiorina also describes how the Russians used to pile the corpses onto a flat-bed train car. This image is not so unbelievable when you consider that harsh Siberian winters made the frozen ground too hard to dig graves except in the warmest months of the year. I assume Fiorina heard these details directly from her father, but my experience with my father’s stories makes me suspect that Trentini men might sometimes tell ‘softer’ versions of the same story to their daughters than to their sons. After hearing all the family stories, and reading various historical accounts, my own belief is that my grandfather may well have been left for dead by the Russians when they were getting ready to abandon the camp after the 1917 revolution (and was possibly dumped amidst the many unburied dead bodies), but his escape entailed no deliberate trickery on his part.

Percy and I went on to talk about my grandfather’s homecoming, and how my grandmother – after she got over the shock of seeing him alive – made him burn his clothes and scrub down his hair and body with kerosene (Percy thought I had said KETCHUP when he heard this story on a previous occasion!) to kill off all the germs, fleas or whatever else had made its home on him over the past two to three years. When he was finally free of vermin (but probably stinking of kerosene), my grandmother welcomed him into the house, where my grandfather finally got to meet his baby daughter, Luigina (whom I knew as Aunt Jean), who had been born while he was in Russia.

Ancestry and the ‘Butterfly Effect’

After we spoke about my grandfather, I said, ‘There’s someone else I’d like to tell you about – my grandfather’s uncle. His name was also Luigi, but his last name was Parisi. The reason I want to tell you about him is that if he had never lived, you and I would probably never have been born, and we wouldn’t be talking about all these stories today.’

I explained how Luigi Parisi – the younger brother of my grandfather’s mother – had gone back and forth from Trentino to America four times. Each time he went to America, he worked in the coal mines, earning money that he sent back to his wife and children back in Duvredo in the parish of Bleggio. While he was away on one journey, his wife Emma died, leaving their children without anyone to care for them. Luigi came back to Bleggio and married Emma’s sister, Ottavia. Together they had four more children (one died young), and named their first daughter after Emma. I told Percy how Luigi had come home to see his family in 1914, but was sent to war, where he died. I recounted a story I had read in a book where one of his comrades said Luigi simply disappeared when they were crossing a river together somewhere in Russia. One minute he was there, and the next he was gone. Nobody knows whether he was shot, or the current of the river got hold of him and he drowned. To this day – 100 years later – his official status is still ‘missing’.

‘Now, shall I tell you why I said you and I would probably never have been born if it weren’t for Luigi?’ I asked.

‘Go on, then,’ Percy replied.

‘Well, according to a book I have, my great-great uncle Luigi Parisi was the first person from my father’s parish (perhaps even from all of Trentino) to settle in the mining town of Brandy Camp in Pennsylvania. He went there first as a young man, around the time my grandfather was born. Each time he went back to Trentino, he brought more men from his village with him, and helped them to settle into their new surroundings. Over time, almost all the Trentini settlers in Brandy Camp came from Santa Croce del Bleggio. That’s why they named their new church ‘Holy Cross’ (which is what Santa Croce means). When my grandfather was a teenager, his uncle Luigi brought him and his younger brother, Angelo, with him to Brandy Camp. There, my grandfather worked in the mines for several years.

‘Finally, when 1914 rolled around, Luigi told my grandfather that he wanted to go back to visit his wife and children. By this time Uncle Luigi was getting close to 50 years old, so he was probably hoping to settle down and spend his later years in his native homeland. But (or so I heard from my cousin Aldo, the son of Angelo), Luigi also thought it was time for my grandfather, now 25 years old, to go home and find himself a wife. Aldo told me that my grandfather didn’t really want to go back to Bleggio, as he had become accustomed to his life in America. But he respected his mother’s brother, and eventually agreed to go back with him in the spring of that year.

‘My grandfather married my grandmother in May 1914. By August, World War 1 had broken out, and most of the local men – including my grandfather, my great-great-uncle Luigi and my grandfather’s brother Angelo – were sent to fight in Russia. As I told you, Luigi Parisi died, but my grandfather and his brother both survived. After the war, my grandfather spent some time recuperating from the trauma of the war and imprisonment. That’s when my father and his younger sister, Pierina (whom I knew as aunt Ann), were born.

‘After a few years, my grandfather went back to America, to the same place his uncle Luigi had brought him – Brandy Camp. After he got settled in, my grandmother, my father and my dad’s sisters followed. My aunt Fiorina was born during their stay in Brandy Camp. Later, they moved to New York where another child – my uncle Raymond – was born. My mother (who wasn’t from Trentino) lived in New York. She became best friends with my father’s sister, Pierina. Later, she and my father fell in love and got married, and started their own family.

‘So you see, Percy, if Luigi Parisi had never lived, he wouldn’t have gone to Brandy Camp and started a community there. He would never have brought my grandfather to America when he was a teenager, or insisted my grandfather get married in 1914. If that had never happened, my father might never have been born, or the family would never have gone to America. If they had never gone to America, my parents would never have met. If they hadn’t met, I wouldn’t have been born, or your mother, or you. And if neither of us had been born, we wouldn’t be talking on the phone right now!’

Percy became excited. ‘Well, you can also say that if Luigi’s FATHER had never been born, then HE wouldn’t have been born, and we wouldn’t be here either. I mean, you can keep going backwards….’

‘Exactly!’ I said. ‘Every single person in our ancestry has played a part in making us who we are, even if we don’t know them, or we’ve never heard of them.’

I didn’t say this to Percy at the time, but it’s just like that science-fiction concept, the ‘butterfly effect’, where everything in the future changes when you change even one, seemingly disconnected event in the past.

Filò – How Stories Keep Our Ancestors Alive

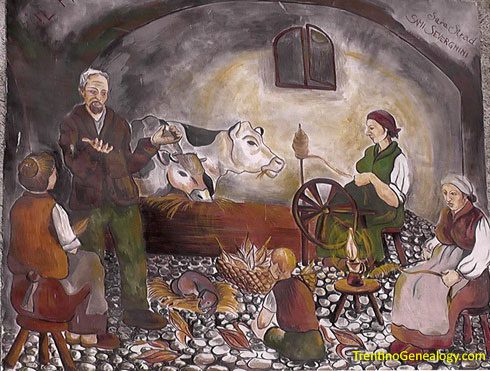

When I first reconnected with my long-lost family in Trentino in the summer of 2014, I visited the hamlet of Favrio in the town of Ragoli, where my Serafini ancestors lived before they moved to the parish of Santa Croce. In the historic quarter of that town, you’ll find many fascinating murals illustrating the history of our Alpine people. One of these murals (see image above) depicts the ancient practice of filò – family storytelling.

Filò was the time – between dinner and bedtime – when families came together to tell and listen to stories. Families would gather, either around a hearth or in the stable (typically on the first floor of their mountain house), where they could benefit from the body heat radiating from their livestock. Traditionally, the storyteller was the head of the household, who wove tales from local legends, family history or his own imagination.

Literally, the word filò means ‘spinning’. Many people say that filò is so-named because women used this time to spin their yarn while listening to the stories. While that may be tree, I also believe it refers to the ‘spinning’ and weaving of the tales themselves.

Filò served as entertainment in an age before radios, televisions and computers. In fact, when I asked my cousins when the tradition stopped, they said it phased out pretty much when radio became popular. It was also simply a time for families to bond and spend time together after a hard day’s work. It was a way of enjoying humour, passing down traditions and instilling cultural values. But, most relevant to what I’ve been talking about today, it was a way bring back to life those who lived before us.

My grandson Percy had no idea that last night – almost instinctively – he and I were sharing filò.

I guess it’s in our blood.

What is ‘true’ in history is only partially made up of facts, dates and evidence. The rest is down to us – our stories, our imaginations, our memories.

We are our stories.

Our ancestors continue to live through our stories. We will continue to live through the stories our grandchildren tell THEIR grandchildren.

Keep telling stories. And don’t wait for the next Giorno di Morti to come for your storytelling hour. Share a story with someone in your family today.

I invite your reflections about family storytelling, or any other topic to do with Trentino Genealogy. Please feel free to express yourself by leaving a comment in the box below, or drop me a line using the contact form on this site.

Until next time, enjoy the journey.

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

P.S.: I am going back to Trento to do research in March, 2018. If you would like me to try to look for something while I am there, please first read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. I look forward to hearing from you!

Subscribe to receive all upcoming articles from Trentino Genealogy!

Desktop viewers can subscribe using the form at the right side at the top of your screen.

If you are viewing on a mobile device and cannot see the form, you can subscribe by sending a blank email to trentinogenealogy@getresponse.net.

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

View My Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

LYNN SERAFINN is a bestselling author and genealogist specialising in the families of Trentino. She is also the author of the regularly featured column ‘Genealogy Corner’ for Filò Magazine: A Journal for Tyrolean Americans.

In addition to her work for clients, her personal research project is to transcribe all the parish records for the parish of Santa Croce del Bleggio (where her father was born) from the 1400s to the current era, as well as to connect as many living people as she can who were either born in Bleggio or whose ancestors came from there. She hopes this tree, which already contains tens of thousands of people, will serve as a visual and spiritual reminder of how we are all fundamentally connected.

View the Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

CLICK HERE to view a searchable database of Trentini SURNAMES.