Origins and connections of five ancient Albertini lines of Trentino.

Revò (and Romallo), Brez, Fisto di Rendena, Premione, Val di Rabbi.

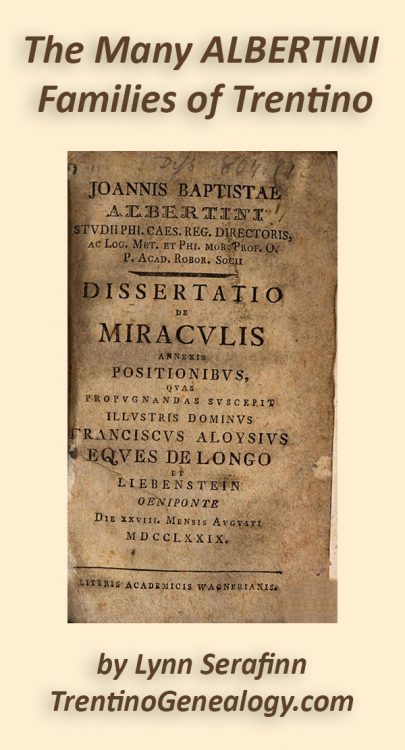

Plus a short biography of 18th century philosopher Giovanni Battista Albertini. By genealogist Lynn Serafinn from Trentino Genealogy.

Want to keep this article to read offline? You can purchase it as a 24-page printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, appendices, maps, footnotes and resource list.

Price: $2.75 USD.

Available in Letter size or A4 size.

| Buy LETTER-size PDF: | |

| Buy A4-size PDF: |

OR, CLICK HERE to find this and other genealogy articles in the ‘Digital Shop’.

INTRODUCTION

Albertini is a patronymic surname derived from the male personal name ‘Alberto’ or its affectionate form ‘Albertino’. Hence, the surname simply means ‘(child/descendant) of Alberto/Albertino’. Linguistic historian Aldo Bertoluzza, who says ‘Alberto’ is actually a short form of the medieval name ‘Adalberto’, includes Albertini among the dozens of surnames derived from medieval personal based on the Germanic root word ‘Bert’ or ‘Bertha’ (meaning ‘splendid, noble, illustrious, famous’).[1]

Like many (if not most) patronymics, this surname does not just appear in various parts of the province, but in other parts of Italy as well. In fact, with an estimated 3532 Albertini families living in Italy today, it is not a particularly uncommon surname. It is found in the greatest concentration in the north, in the regions surrounding Trentino-Alto Adige (Lombardia, Emilia-Romagna, Veneto), but in the province of Trento (AKA Trentino) itself is home to only about 150 of these families, with more than a third of them living in the city of Trento.[2]

The statistics for city of Trento are more a reflection of urbanisation over the past two centuries rather than an indicator of ancestral origins, however.[3] Indeed, the places in which the Albertini have the most ancient and prolific presence are all rural villages, most specifically:

- Revò (including Romallo), in Val di Non

- Brez, also Val di Non

- Fisto, Spiazzo Rendena, in Val Rendena

- Sclemo and Premione (Val Giudicarie Esteriore)

- Val di Rabbi

In this article, we will examine the early generations of these five ancient lines, along with several branches in other places (some now extinct) whose origins can be traced back to one of these five. At the end of the article, we’ll consider possible ancestral links between these ancient lines, as well as questions about their ancient origins, while offering suggestions for further research.

As we meet the various Albertini families of Trentino, we find that they were not nobility. Also, although some Albertini from Rendena were notaries, most other branches were not typically engaged in such ‘white collar’ occupations. Rather, while some were surely contadini (subsistence farmers), we find a proliferation of artisans, engaged in variety of highly skilled crafts, including masonry, carpentry, blacksmithing, tailoring, cobbling/shoemaking, etc. Such occupations were held in high regard before the age of technology, and they also enabled families to move from place to place more easily than those who were dependent upon a particular plot of farmland for their livelihood.

And, like many other Trentino families of the past, the Albertini also produced a good number of Catholic priests, some of whom became renowned intellects of their times. Later in this report, we will examine in some detail the interesting life of one of the most renowned personalities who bore the Albertini surname – philosopher, author, academic, and Jesuit priest, Giovanni Battista Albertini of Brez (1742-1820).

IMPORTANT: Although they share a similar linguistic root, Albertini is NOT the same surname as Alberti, de Alberti, Alberti de Poja etc., and they do not share a common ancestral connection.

PART 1: Revò and Romallo (Val di Non)

The earliest recorded document I have found containing the surname Albertini is from 1480 wherein an Albertino Albertini of Revò is being held accountable for a debt owed to one of the lords of Castel Cles.[4] Any time we see a man named in a legal document, we can assume he was at least 25 years old, which was then the age of majority. Thus, we can assume Albertino was born no later than 1455, and possibly much earlier (after all, it takes time to go into debt!).

It would be incorrect to assume that this Albertino was the patriarch from whom the surname was derived, as we see he was already called ‘Albertini’. But if we were lucky enough to find documents that go back a few more generations – say, to the early 1300s – I am confident we would eventually find a man referred to as ‘Albertino of Revò’ (or wherever he happened to be living), who was a paternal ancestor of this Albertino. In my research on early Trentino surnames, I have frequently found that the patriarchal personal name is frequently reused in subsequent generations, sometimes for a century or more.

Unfortunately, the surviving records for the parish of Revò do not go back as far as we might like. The baptismal records start in 1619, and the marriages in 1624. However, there is census for the parish that was taken in the summer of 1624, which helps to extend our understanding of the families living in Revò and its various frazioni before the year 1600.

Albertini in Revò in 1624

The 1624 census records two Albertini families living in Revò:

- Domenica (age 48), wife of the late Giovanni Albertini, with her unmarried sons Nicolò (age 25) and Lorenzo (age 23).[5] Both sons lived full lives with families of their own, whose descendants continue to the present day.

- Antonio Albertini (age 30) and his wife Giacoma (age 28) with their infant daughter Cattarina (she was born 1 March 1624)[6], along with Antonio’s unmarried siblings: Anna (age 28), Orsola (age 20) and twins Maria and Giovanni (age 18).[7] One would assume that the parents of Antonio and his siblings were already deceased. The line of male descendants for this branch appears to have died out shortly later.

Albertini in Romallo in 1624

The 1624 census tells us of another Albertini family group living in the frazione of Romallo, albeit you might miss them if you look too quickly, as the they are recorded under their soprannome. The priest calls them ‘Furlanus, called “Bertini,’[8] ‘Furlana’ (or similar) apparently referring to the house or neighbourhood in which they were living.

This family group is interesting because, rather than parents and children, we find an unmarried paternal aunt (‘amita’), Cattarina (age 25), living with her nephew Giovanni (age 7) and niece Anna (age 8). This Giovanni married in 1637, fathering at least seven children with his wife, Cattarina Giosetta,[9] albeit most died at an early age. We continue to see the soprannome Furlan in their children’s baptismal records, but after a decade or so, they drop the soprannome, and go back to using only their original surname, Albertini.

Two of Giovanni’s surviving sons – Stefano and Giovanni Albertini – married sisters Maria and Domenica Gentilini, also of Romallo.[10] While I have found no children for Stefano and his wife Maria, at least 9 children of Giovanni and Domenica are recorded in the Revò baptismal register. Again, the majority died in infancy/childhood, but the three who managed to survive to adulthood were all sons (Giovanni, Giacomo, and Bartolomeo). All of them married and had many children, firmly establishing the Romallo branch of Albertini. This line has continued in Romallo to the present day, and it also expanded into other parts of the province in later centuries.

Eighteen Albertini of Revò and Romallo Rabbi were enlisted in the military during the First World War (See APPENDIX 1 in PDF eBook for details).

Albertini Branches Originally from Romallo

Cloz

In the early 19th century, two brothers descended from the ‘Furlan’ Albertini of Romallo started two new branches of Albertini outside the parish of Revò.

Sons of Stefano Albertini of Romallo and Teresa Martini of Revò,[11] the elder of the brothers was Giovanni (baptised Giovanni Battista), who was born 22 September 1787. On 2 July 1815, he married Maria Franch (daughter of the late Giorgio) of Cloz, settled in his wife’s parish. Although the appear to have had only two children, descendants of their son Stefano Pasquale,[12] continued through the end of the 19th century, after which it appears to die out in that parish.

In his 1842 marriage record with Margherita Franch, Stefano Pasquale is said to be a mason (muratore),[13] which appears to have been a family occupation (and I suspect his father was also a mason).

Riva del Garda

The other child of Stefano Albertini and Teresa Martini who left his native village of Romallo was their much younger son Stefano, born 16 April 1798.[14] By the time he was in his mid-20s, we find this Stefano living for a short while in Arco, and then moving to Riva del Garda, in the southernmost part of the province. In 1826, he married Vittoria Leonardi of Ceole (a frazione of Riva).[15] The couple raised their family of 11 children in Varone, another frazione in that parish. Like his nephew in Cloz, this Stefano was also a mason, an immensely ‘transferrable’ trade to have, which would surely explain why this branch of the family were so mobile. Noticeably, Vittoria’s father was also an artisan, i.e., a cobbler.

In the first decade of the 20th century, we find Stefano’s grandson, Vicenzo Alessandro Albertini (born 25 August 1871) moving around to various places with his wife Matilda Flatscher, as he was apparently the ‘capoparto’ of the gendarmerie (department head of the military police).[16]

There are still some Albertini from this line living in Riva today.[17] Some descendants migrated to North America (one of my clients is descended from this line).

Arco

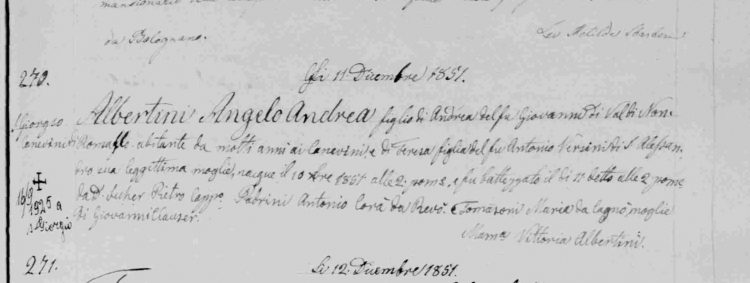

Another Albertini branch with roots in Romallo started in Arco in the mid-19th century when Giovanni Andrea Albertini (usually known only as ‘Andrea’) of Romallo[18] settled in the locality of Giorgio in the parish of Arco. He married Maria Teresa Versini of frazione of Grotta, and the couple had six children – all of them sons – between 1846-1858.

In the baptismal record of their fourth son Angelo Andrea, the priest says that Andrea ‘has lived for many years at the canevini of San Giorgio’:[19]

Canevini are rock-hewn enclosures (fitted with heavy wooden doors), designed for cold food storage in the mountains. They were, in effect, natural refrigerators and pantries, used for centuries by our mountain-dwelling ancestors before the dawn of technology. From what I have read, they appear to have belonged to (and been used by) the community, rather than privately owned.

Although Andrea is referred to as a contadino in one record, I cannot help but feel that he may have something to do with the maintenance and operation of the cold food storage at the canevini. I have no idea if this was actually the case, but I cannot help but wonder why you would live near them (rather than in the village) if you didn’t have something to do with them on a daily basis.

The descendants of this line still live in Arco today, albeit only a handful.[20]

PART 2: Brez (Val di Non)

The parish of Brez (sometimes called Arsio e Brez) has been home to the Albertini at least since the mid-1400s. The earliest reference to the surname I have found in Brez is for an Antonio Albertini, who is listed as one of the vicini (official citizens) present at the drafting of the Carta di Regola (Charter of Rules) for Arsio on 17 May 1492.[21] [22] As a legal adult and householder, Antonio would have been born no later than 1467, and possibly much earlier. Also, to be consider a vicino, his family would have to have been living in that community for at least a generation before. Although Antonio is the only Albertini present at the event, he apparently had the soprannome ‘Antoniol’, which is a good indication that there were other branches of Albertini living in Brez at that time.

Moving forward in time, on 5 August 1514, we find a ‘Maestro calzolaio’ (master cobbler) Nicola (Nicolò) Albertini of Brez cited as being the rector of the Chapel of Santi Michele, Marco e Luca inside the parish church of San Floriano in Arsio, and the drafting of a copy of a document originally drawn up in 1500.[23] Note that, in this era, the term ‘rector’ was a title given to senior officials with governmental, administrative, or judicial positions, and it did not refer to a priest. The local parish church was not just a place for religious events and vital records (such as baptisms, marriages, and deaths), but it was also an official office of local government, where legal documents were drafted and stored.

Author Bruno Ruffini tells us there were four Albertini of Brez present at the drafting of a Carta di Regola on 1 September 1520: Stefano Albertini (a regolano of Castel Bragher), the same Nicolò Albertini mentioned above, and two Albertini brothers named Bartolomeo (a blacksmith) and Simone.[24] From a document in the Arsio archives, we learn that Stefano was deceased before December 1548 (there was apparently a younger Stefano who was also a regolano of Arsio).[25] From the parish register, we learn that Nicolò was deceased when his unmarried daughter Lucia is a godmother on 30 July 1555.[26]

This brings us up to the time when churches started recording births and marriages in the mid-1500s (most started recording deaths slightly later). The earliest Albertini marriage I have found in that parish is for a Giovanni Albertini and Maddalena Calovini, daughter of Pietro, of Cloz, who married dated 18 January 1593.[27] His father’s name is not mentioned, and I have found no children for them in the register, but we can estimate Giovanni may have been born sometime around 1565-1570 if this was a first marriage, or somewhat earlier if Maddalena was his second wife.

Although the surviving baptismal records for Brez start in 1554, they are in extremely poor condition, with almost no mothers’ names recorded, the occasional omission of surnames, and particularly challenging handwriting. Then, they stop at 1563, at which point there is a gap until 1581. From these fragmented records, I have identified at least three early Albertini family groups, whose patriarchs (Bartolomeo, Giacomo, and Romedio Albertini) where most likely born sometime within that 18-year gap, as their children were born in the 1590s through the first decade of the 1600s.

Even in these early families, we start to see the Albertini spreading out within the parish, some to the frazioni of Traversara and Rivo.

The surname continues to flourish in the parish of Brez today. There are 207 Albertini listed on the Nati in Trentino website, who were born in the parish of Brez between the years 1815-1923.[28] Ruffini says there were a good 46 Albertini of Brez who emigrated to America between 1870 and 1924, only of few of whom returned to their homeland.[29]

Fourteen Albertini men from Brez enlisted in the military during the First World War, one of whom died in battle (See APPENDIX 1 in PDF eBook for details).

Among persons of note from the Albertini of Brez, was one Giovanni Battista Albertini (1780-1855), who was an esteemed professor of world history in Innsbruck, and later a librarian in Trento, where he passed away.[30]

But by far, the most renowned Albertini of Brez was another Giovanni Battista, a Jesuit priest whose progressive writings and controversial views were at the forefront of the Age of Enlightenment at the end of the 18th century. We will now take a brief look at his interesting life.

Giovanni Battista Albertini: Philosopher and Theologian in the Age of Enlightenment

Born in the frazione of Rivo (Brez) on 8 October 1742, Giovanni Battista Albertini was the last child – and only surviving son – of Romedio Albertini and his wife Maria Flor,[31] whom author Ruffini describes as ‘modest contadini.’[32]

From an early age, Giovanni Battista showed signs of high intelligence and a propensity for learning. His parents, who were poor, saw in him an opportunity: if he could devote himself to academic study, he might be able to attain a stipend that could also help support the family.[33] As a teenager, the young Giovanni Battista was sent to be educated at the Ginnasio dei Gesuiti (Jesuit high school) in Trento.[34] By the time he completed his studies there at age 20, the young man decided to dedicate himself to an ecclesiastical career.[35] Having ‘manifested diligence and brilliant intelligence’ and illustrating a hunger for study for a wide range of subjects, including new sciences, he was chosen as one of the top graduates of his class,[36] and was awarded a stipend to study in the department of Philosophy at the University of Innsbruck.[37] In 1766, when he was still not quite 24 years old, he attained his Doctorate from that university, and also took up Holy Orders to become a Catholic priest.[38]

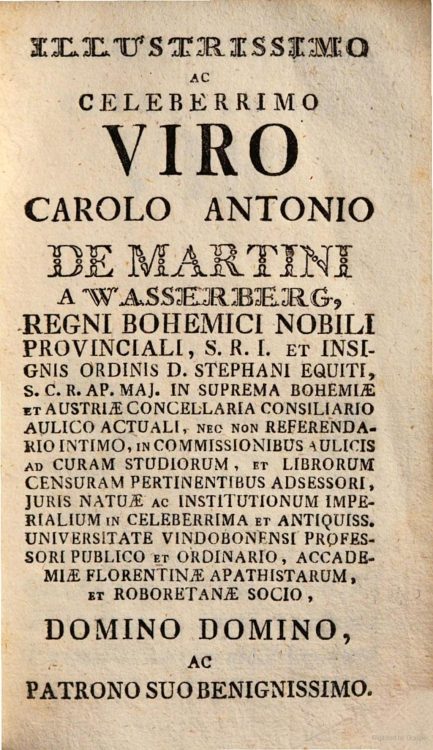

His achievements must have made his parents back in Brez very proud, but sadly, his mother would pass away the following year, apparently after a long illness.[39] Whether or not the young priest came home to see his mother before she died, I cannot say, but we do know that he continued his studies in philosophy in Innsbruck for another five years, after which he went to Vienna to study law. There, don Albertini was known to have associated with his Val di Non compatriot the noble Carlo Antonio Martini de Wasserperg of Revò, then a Professor and Director at the University of Vienna, who had recently been elevated to the rank of Knight of the Holy Roman Empire.[40] His senior by 16 years, Carlo Antonio, who was already deeply devoted to progressive reform in the legal system (and would later be a major contributor to educational reform with Empress Maria Theresa), would surely have been a major influence on Giovanni Battista, both intellectually and professionally.

In 1774, at age 32, he was made a Professor at the University of Innsbruck. His father Romedio would not have lived to see his son attain this achievement, however, as he had passed away the previous year.[41] A few years later, in 1778, Giovanni Battista became Rector of the university; the following year the titles of president and professor of Logic, Metaphysics and Moral Philosophy were added to his role. Altogether, he would hold these prestigious academic positions at the University until its dissolution in 1783.[42]

During his years at the University of Innsbruck, Albertini became renowned (if not infamous) for his progressive thought and philosophical research, which he shared in some of his most important treatises, including:[43]

- Dissertatio de conscientia dubia (1775)

- Dissertatio de rerum interna possibilitate (1776)

- Dissertatio de natura animae humanae (1778)

- Dissertatio de miraculis (1779)

Notably, the noble Lord Carlo Antonio Martini is cited as his most benevolent patron on the frontispiece of the 1778 work, Dissertatio de natura animae humanae (Dissertation on the Nature of the Human Soul).

To understand this chapter of the life of Giovanni Battista Albertini, as well as to what would happen in the decades to follow, it is worth taking a moment to consider the ‘Zeit Geist’ of the times in late 18th century Europe.

In this era, advancements in the sciences and a shift towards scientific methodology had begun to filter into the realms of philosophy and logic. With this, we see new ideas emerging on economics and social structure. While there had been numerous ‘rebel uprisings’ throughout the centuries against the monarchy, the nobility, and/or the Pope, these had always been suppressed. But now, in the latter half of the 1700s, these kinds of ‘enlightened ideas’ were reaching a tipping point, evolving into an unstoppable wave that became, quite literally, social revolution.

In a culture where the institution of the Church had for so long been inseparable from the ruling body, we now find the radical idea of ‘separation of Church and state’. In a society where, for nearly 1,000 years, the socio-economic structure had been a rigid, hierarchal feudal system, the institution of the monarchy and the privilege of the noble classes were being challenged, with another radical idea called ‘democracy’ was being proposed as an alternative.

As one might imagine, the ideas arising from the scientific advancements and social philosophies of this ‘Age of Enlightenment’ would also influence the thinking of scholars within the Church itself, and many of the tenets of the Catholic faith became topics of heated debate. Two such tenets were the concept of the Immaculate Conception and the primacy of the Pope. Giovanni Battista Albertini was one such scholar to challenge these and other long-held beliefs. Undoubtedly influenced by the strong liberalism that was characteristic of secular intellectuals in Innsbruck at the time, his ideas were distinctly opposed to many of the traditional views of the Jesuits.[44] Ultimately, his outspoken liberalism made him a target of much criticism, if not professional sabotage, which were to reach a boiling point by the end of the 1780s.[45]

During those years, we also start to see a shift in society at large. What was once an era of inspired, ‘enlightened’ free-thinking, began to devolve into full-fledged revolutionary activity, marked by violence, wars, and massive social upheaval. In the last three decades of the century, we see both the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) and the French Revolution (1789-1799). By the end of the century, and into the early 1800s, we find Napoleon who, in my opinion, exploited the social philosophies of the previous generation as moral justification for his own, distinctly immoral, tyrannical behaviour.

Possibly equally opportunistically, we see this Zeit Geist appearing within Austria as well. In late 1783, as part of his desired reorganization of higher education within the Holy Roman Empire, Emperor Joseph (Habsburg) II, the University of Innsbruck was disbanded and replaced with a secular high school (Liceo), along with a general seminary, for the training of the clergy. Of the 25 professors at the University, only 12, including Albertini, were selected to remain as teachers in the newly restructured school,[46] and was assigned the role of Rector of the new seminary.[47]

At face value, this might all sound very positive, but the reality of the situation was complicated, if not utterly paradoxical. The members of the newly formed general seminary where required to swear an oath which said, “I believe everything that the true Church believes, and I swear obedience to his majesty the Emperor”.[48] Just what was ‘the true Church’ in this era, and just want did this true Church now believe? Moreover, as the Emperor was charging them with the mission of bringing the seminary into the ‘new era’ of thought, how could they possibly be obedient both to him and to the Church, simultaneously? Certainly, this oath would have been the source of many a personal moral conflict.

What made Albertini’s situation even more complex is the fact that he was not just a priest, but he was also a freemason. Surely driven by his own spirit of freedom of thought, speech, and writing, he joined the society of freemasons in Innsbruck 1779.[49] A powerful and influential social organisation, the Innsbruck freemasons shared a vision of the abolition of feudal class privileges and social injustices, and aspired to exemplify how democracy worked within its lodge. Interestingly, there were many other Trentini among its members.[50] Personally, I find this unsurprising as, although Trentino had been part of the feudal system for centuries, local Trentino communities had long been managed by a system of (loosely democratic) self-government, via their tradition of the Carta di Regola.

Between his own progressive beliefs, and the actions of the state, Albertini now found himself in a most difficult and stressful situation. In 1787-88, the bishops of Trento, Bressanone, Chur and Constance began a battle against Emperor’s establishment of a state institute for the training of the clergy.[51] In their quest to discredit the General Seminary, they aggressively accused the faculty of teaching false doctrines, tainted by political agenda and other ideas that were irreconcilable with the official doctrine of the church. Of course, as Rector of the seminary, Albertini was the primary target of these accusations.

Emperor Joseph II passed away on 20 February 1790, and his successor Leopold II did not particularly wish to inherit the ongoing battle with the Church over what was seen as interference in ecclesiastical affairs. And so, on 4 July 1790 Emperor Leopold decided to close the General Seminaries, with the excuse (possibly to save face) that they cost the state treasury too much to operate.[52] Now finding himself without employment, Giovanni Battista Albertini was officially retired via a court decree on 28 December 1790, and given an annual pension of 900 florins.[53]

He remained in Innsbruck another five years, and then moved to Klagenfurt (Austria), where he was ‘revered and loved by all’ and was ‘truly in philosophical repose’.[54] Remaining in Klagenfurt for 11 years, Albertini became increasingly withdrawn. Certainly exhausted by years of intense work and emotional conflict, and deeply affected by the extremism of the Jacobin revolutions and the Napoleonic conflicts at the end of the century, he became weakened both physically and mentally.

After briefly returning to Innsbruck in 1807, he was sent to the city of Trento by the Bavarian government, charging him with the task of organising the studies of theology and philosophy at the Liceo there.[55] But his former critics did not remain silent for long, and became increasingly hostile to him, calling him ‘that infamous Albertini, a well-known Freemason’, the ex-rector of the Seminary of Innsbruck, ‘where flawed professors held professorships, who taught erroneous doctrines contrary to the Church.’[56] Thus, his time there was short-lived.

Jobless once again, Albertini’s already difficult situation was to get worse. In 1810, in the aftermath of the Napoleonic invasions, the Tyrol had been divided between Bavarian and Italian authority, and would remain so until its reunification and return to Austria in 1814. During this period, the Italian regime refused to pay Albertini his 900-florin pension, effectively leaving him destitute.[57]

Now in his late 60s, Albertini returned to Brez, the parish of his birth. Another Brez-born priest named Vincenzo Avancini, a beneficiato of the Borzaga family,[58] welcomed him into his home and cared for him until Albertini’s death. The Countess of Arsio came to his financial aid, and the Vice Prefect ‘von Filos’ worked for two years to finally get his pension reinstated.[59]

But whether from the culmination of his stressful life, or simply natural causes, the ageing priest started showing signs of some form of dementia. Although he had occasional days of lucidity, much of the time he did not recognise anyone, with the exception Avancini, whom he is said to have ‘followed like a child’. He spoke very little, or sometimes spoke a ‘language’ nobody could understand. He alternated between days where he ate and drank normally, and other days where he would neither eat nor move, simply staying in bed.[60]

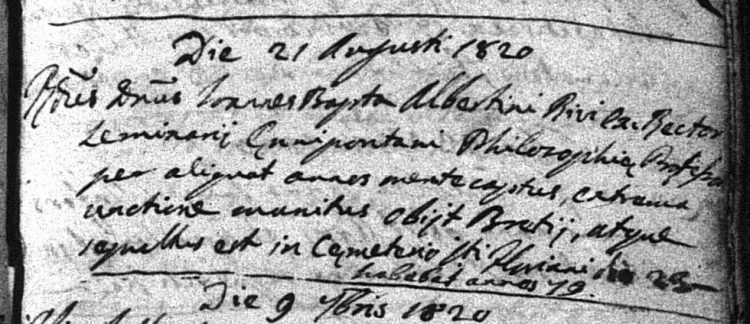

Eventually, he was released from his suffering, departing this world on 21 August 1820. His death record, recorded by the parroco of Brez (Giovanni Paolo Colò), reads:

21 August 1820.

The Reverend dominus Giovanni Battista Albertini of Rivo, former Rector of the Seminary in Innsbruck, Professor of Philosophy for many years, mentally disturbed, having been comforted by Extreme Unction (last rites), died in Brez, and was buried in the cemetery of (the church of) San Floriano on 23 (August). He was 79 years old.[61]

SIDENOTE: Albertini had not quite reached his 78th birthday when he died. Also, the recording priest has used the term ‘mentecaptus’, which some dictionaries translate as ‘crazy’. Both Farina and Ruffini use the word ‘pazzia’, which is generally translated as ‘madness’. I have opted to use the somewhat softer and less judgmental term ‘mentally disturbed’.

PART 3: Fisto, Spiazzo Rendena (Val Rendena)

Another ancient Albertini family is found in Val Rendena. Although most commonly found in the frazione of Fisto in the present-day comune of Spiazzo Rendena, the earliest mention of an Albertini in Rendena I have found is in a land sale agreement dated 9 February 1478 by a Giacomo Albertini (son of the late Tomeo) of Borzago (another frazione in Spiazzo).[62] A few years later, in 1484, we find a master tailor named Biagio Albertini (son of the late Giovanni) cited as one of the sindaci (mayors) of Caderzone, which is about 4 km north of Fisto.[63] From these references, we see there were already at least two Albertini lines living in Rendena at the time, and we can estimate that the late fathers of the two men were born sometime in the early decades of the 1400s.

From 1530s onwards, the majority the Albertini families in Rendena are cited as being from Fisto.[64] On 10 June 1532, for example, we find an Ognibene Albertini of Fisto active as a ‘public messenger’ for the curia of Tione, publishing a decree made by the Vicar of the valley regarding certain environmental regulations (cutting of trees, grazing on lands by non-residents, etc.).[65] We find this same Ognibene working in this same role as late as 1543.[66] [67]

The surname appears in the earliest records for the parish of Spiazzo, which start in 1562. Notably, soprannomi are already being recorded (e.g. Zapani), an indication that there were enough branches of Albertini there to warrant the need to distinguish one from another.[68] P. Remo Stenico lists four Albertini priests from Fisto and/or Rendena, the earliest being a Benedetto Albertini of Vigo Rendena whose name appears in records between 1601-1605.[69]

Towards the end of that century, we start to see notaries appearing among the Albertini of Fisto. There is, for example, Giacomo, son of the late Alberto ‘Dossi’ Albertini of Fisto in 1583.[70] Later, find an Antonio Ognibene Albertini of Fisto (son of the sindaco Cristoforo ‘del Fra’ Albertini, who was son of another Antonio)[71] [72] working as a notary in the early 1620s.[73] As the notary profession tends get passed down from father to son, the Albertini of Rendena might possibly be descended from a medieval notary known only as ‘Albertino of Fisto’, whose name appears in legal documents as early as 1305,[74] but of course this is highly speculative.

Twenty-two Albertini of Rendena were enlisted in the military during the First World War, one of whom died in battle (See APPENDIX 1 in PDF eBook for details).

An estimated 17 Albertini live in the Spiazzo/Pinzolo area today.[75]

PART 4: Sclemo and Premione (Val Giudicarie Esteriore)

No later than the end of the 1500s, the surname Albertini starts to appear in the village of Sclemo, a frazione in the present-day comune of Stenico in Val Giudicarie. We find, for example, a Pietro Albertini of Sclemo marrying a Margherita Castagnari, also of Sclemo, on 25 July 1621.[76] We also find an Antonio Albertini of Sclemo and his wife Domenica Tisi, having children in the 1630.[77] Curiously, these are both Rendena surnames. But as the wording in the documents say ‘of Sclemo’ rather than ‘living in Sclemo’, we can presume these Albertini were native to that village, rather than being recently arrived there.

At least by the beginning of the 1700s, the surname also starts to appear in Premione, another frazione in the comune of Stenico. On 29 January 1749, for example, we find a baptismal record of a Giovanni Albertini, whose living grandfather (also named Giovanni) is said to be a carpenter (fabri legnari) from Premione.[78] Again, the wording ‘of Premione’ rather than ‘living in Premione’ infers he was native to that place. Thus, we can estimate that this elder Giovanni may have been born in Premione sometime around the last decade of the 1600s.

Although I haven’t researched this yet, I would imagine the Premione line originally moved there from Sclemo, as the two villages are only about 2 kilometres away from each other, and they are also in the same parish of Tavodo. If so, this appears to have been a permanent shift for the last of the Sclemo Albertini, as we find no Albertini listed in the 1751 Carta di Regola for Sclemo,[79] and any Albertini I have found in this area in later years came from Premione.

Eight Albertini men from the comune of Stenico were enlisted in the military during the First World War (see APPENDIX 1 in PDF eBook for details).

An estimated 19 Albertini live in the comune of Stenico today.[80]

PART 5: Val di Rabbi (Val di Sole)

The last Albertini line we will look at are the Albertini of Val di Rabbi, which is often considered to be a sub-valley of Val di Sole. We know the Albertini were present in the parish of San Bernardo di Rabbi (a curate parish of Malé), at least by the late 1500s.[81] We find, for example, the baptismal record of twin girls Maria and Maria Margherita, daughter of Giovanni Albertini of Somrabbi, on 12 September 1580.[82] We find this same Giovanni deceased in a legal parchment drafted on 20 August 1594, with the mention of the ‘heirs of the late Gioannino (i.e. Giovanni) Albertini of Somrabbi’.[83]

P. Remo Stenico cites the names of three priests from Piazzola di Rabbi, but only from the late 18th century onwards.[84]

There were 171 Albertini born in Val di Rabbi between the years 1815-1923.[85] Fourteen Albertini of Rabbi were enlisted in the military during the First World War, two of whom died in battle (See APPENDIX 1 in PDF eBook for details).

Albertini Branches Originally from Rabbi

Malé

On 25 August 1612, we find the birth of a Cattarina Albertini born in the parish of Malé in Val di Sole, whose father Antonio is said to have come from Rabbi (although he apparently spent some time in Mantova before settling there).

In the 1644 Carta di Regola for Malé,[86] only one Albertini citizen is mentioned: an Andrea Albertini (who may be Antonio’s son, but I have not found a baptismal record for him). In that document, Andrea is cited as being a jurist and ‘saltaro’ (a type of local authority). The Malé parish register shows us that Andrea was married and head of a family during this era.[87]

The Albertini last child from this Malé branch was born in 1884, after which the line either died out or moved away.

San Giacomo

Also with their roots in Val di Rabbi, another Albertini line started in San Giacomo in the comune of Caldes (also n Val di Sole), when a Giacomo Antonio Albertini of Rabbi married a Lucia Peroceschi of San Giacomo in 1738. The couple had at least 7 children between the years 1738-1751.[88]

The Albertini last child from this San Giacomo branch was born in 1900, so they have also either died out or moved away. We also find no Albertini men from either Malé or San Giacomo listed as enrolled in the military during World War 1.

CONCLUSION: Questions about ORIGINS and Ancient Ancestral Connections

Having looked at these five ancient Albertini lines, the inevitable question we find ourselves asking is:

Are any of these lines related?

Do any of these lines share a common patriarchal ancestor? If so, his name was presumably Albertino, and he most likely lived sometime in 1300s, the century before surnames started to become common practice. Moreover, do all of these lines originate in Trentino, or might they have come from someplace else?

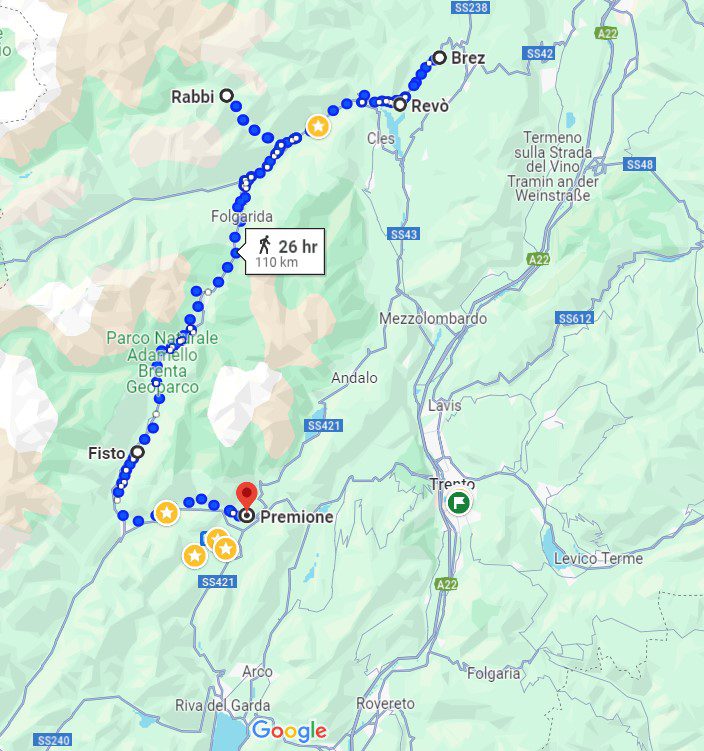

To formulate some theories about probable scenarios, it is worth looking at a map of the five key places we have discussed in this report (screenshot from Google maps):

Trentino is extremely mountainous, and it is difficult to grasp fully the ruggedness of the terrain from any map, especially if you have never been to these places. Essentially, the white and brown areas are the most mountainous, and often have to be driven around rather than across. The light green areas are the valleys, and the dark green areas are the higher elevation peaks, where you will often find woodlands, grazing areas, or malghe (mountain dairies). Generally, people live (and farm) in the valleys.

Revò and Brez

Revò and Brez are very close – only about 6 km (roughly 4 miles) – and are not separated by any particularly difficult natural barrier. As a result, the two parishes interacted quite a bit throughout the centuries, and it was not uncommon to see people from one parish marrying someone from the other, or for families from one parish to move to the other. Given their proximity and cultural history, it seems likely that the Albertini of Revò/Romallo and Brez are descended from a common patriarch. As we know that the surname was already well-established in both places by the mid-1400s, this would indicate that the family would have already split into two lines no later than the early 1400s, and their common ancestor would likely have been born in the early to mid-1300s.

Rendena and Premione, and Possible Lombardian Connections

To me, the other likely connection is between the Albertini of Val Rendena and of Premione. Rendena is actually a sub-valley of ‘Giudicarie Interiore’, while Premione is situated in ‘Giudicarie Esteriore’. The two halves of the Giudicarie are separated by a strip of low mountains, running north-south through much of valley. Thus, places that might seem to be close to each other on the map are not always easy to access, as you have to travel around the mountain to get there. That said, throughout history there have been many families who migrated from one side of the Giudicarie to the other (including to/from Rendena), by looping around the village of Tione. This same route is also used by coach that runs from Trento to Pinzolo today.

Looking at the map, Fisto is located near the southern part of that strip of mountains separating the two halves of the Giudicarie, and is about 22 km (about 14 miles) away from Sclemo, where the Albertini lived before settling in nearby Premione.

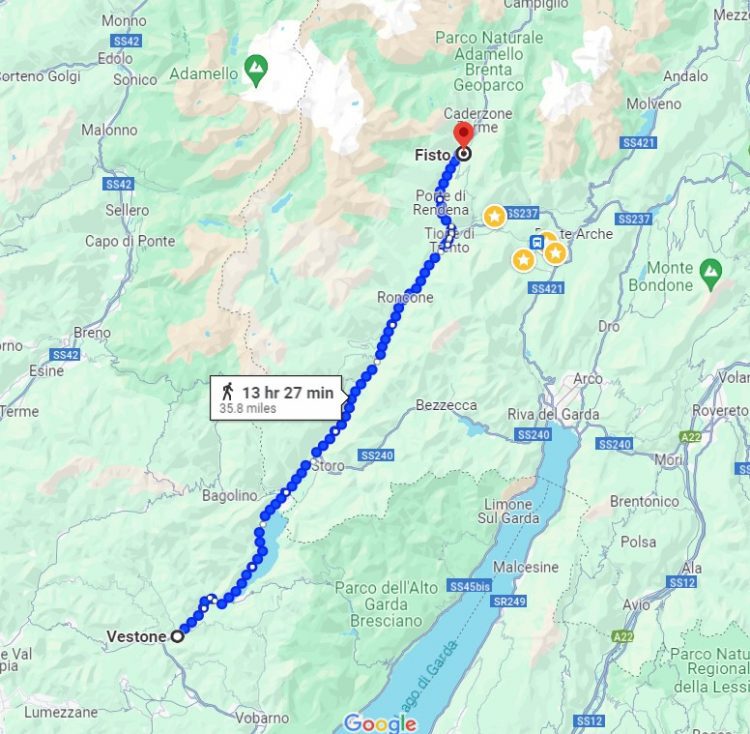

I also cannot help but wonder if this line of Albertini has their origins in Brescia in Lombardia, where there is a high concentration of Albertini families, and is easily accessible to Fisto. The village of Vestone, for example, has the highest number of Albertini families in that province after the city of Brescia itself. We know there was a lot of migration from Brescia into Trentino in the 14th and 15th centuries, especially among artisans and craftsmen seeking work. While I admit this is just my own musing, I feel it is certainly feasible.

Rabbi and Where?

As to the Albertini of Rabbi, I find it a bit more difficult to propose any theories as to connections or origins. Part of Val di Sole, Rabbi is much more rugged, and traditionally had less interaction with Val di Non and Val Giudicarie. They may have been a completely independently arising branch, or they may also have had their origins might be in Lombardia.

Possible Answers via Y-DNA Testing

Barring any future documented evidence that might emerge indicating either a connection between these lines, and/or their place(s) of origin, our best – if not only – resort is to turn to genetics.

A Y-DNA test traces a man’s paternal ancestry, i.e., his father’s father’s father’s father, and so on. In other words, it is the line that carries the surname (barring any ‘unexpected parental events’, such as when you encounter an illegitimate birth).

Only men can take this kind of test because only men have a Y-chromosome. It is not the same kind of test offered via AncestryDNA or 23andMe (those are called ‘autosomal DNA tests), although 23andMe does provide male testers with the name of their broad paternal haplogroup. If you are a female, you might still be able to obtain this information, if you get a male family member to take a Y-DNA test. For example, as my father is deceased and I have no brother, I obtained my father’s haplogroup via a 23andMe test for one of my paternal male cousins (son of my father’s brother).

One of my clients (who is also in our Trentino Genealogy Facebook group) has been coordinating a Y-DNA comparison/analysis chart of Trentini participants for a few years now. So far, we don’t have ANY Albertini testers included in the chart. It would be excellent if we could get at least one Albertini male descended from each of the 5 primary lines I have discussed in this article to take a Y-DNA test and share the paternal haplogroup information with us. You can either send us the haplogroup shown on your 23AndMe test, or from any Y-DNA test on Family Tree DNA (which gives more detail than 23AndMe). Those from branches of those five branches are also welcome to send us their results as well.

Even if your Albertini family came from a village not discussed in this report, your information is welcome.

And, of course, you are welcome to send us Y-DNA information of ANY Trentino male descendant of ANY surname, as long as he is descended via an unbroken male line (for example, if his father is not Trentino, and his Trentino ancestry is via his mother, he would not be able to provide us with the right information).

Please send this information via the contact form on the Trentino Genealogy website. Please be sure to include the following information when sending it:

- The SURNAME of his family (original Trentino form, if it has been changed after immigration)

- VILLAGE OR PARISH of origin of that family OR

- VALLEY of origin (if you don’t know the exact village/parish)

- The Y-DNA HAPLOGROUP

Your participation in this project can really help us more deeply understand the history of our own ancestors, and also to find ancient connections between families that do not have the same surname.

The primary aim of this report has been to examine the earliest generations of five Albertini lines of Trentino. We also examined how some of these lines migrated to other villages, and we briefly looked at the life of 18th-century philosopher and priest, Giovanni Battista Albertini. Finally, we considered possible ancestral connections between these five lines, and offered suggestions for how to take this research further.

I hope you found this article to be both interesting and informative. I look forward to being able to expand this information if/when Y-DNA information sheds new light on their more ancient connections

Want to keep this article to read offline? You can purchase it as a 24-page printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, appendices, maps, footnotes and resource list.

Price: $2.75 USD.

Available in Letter size or A4 size.

| Buy LETTER-size PDF: | |

| Buy A4-size PDF: |

OR, CLICK HERE to find this and other genealogy articles in the ‘Digital Shop’.

If you have any comments or questions, or if you are seeking help researching your Trentino family, please feel free to contact me at https://trentinogenealogy.com/contact.

Until next time!

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

19 February 2024

P.S. I am currently taking client bookings for May 2024 and beyond. (I am also hoping to plan a research trip to Trento sometime this year, but I haven’t set anything up yet). If you would like to book a time to discuss having me do research for you, I invite you to read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, we can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry

(please note that the online version is VERY out of date, as I have been working on it offline for the past 6 years):

https://trentinogenealogy.com/my-tree/

NOTES

[1] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino. Trento: Società Iniziative Editoriali (S.R.L.). See entry for ‘Alberti’ on page 13 and ‘Bert’ on page 39. He says that these personal names first became popular during the era of the Longobards (ca. 400-800 AD).

[2] COGNOMIX. Mappe dei cognomi italiani. ‘Albertini’. https://www.cognomix.it/mappe-dei-cognomi-italiani/ALBERTINI. Accessed 9 February 2024. The site says there are 866 Albertini families living in the region of Lombardia, 717 in Emilia-Romagna, and 691 in Veneto.

[3] I have not yet traced the origin of the Albertini in Trento, but I have found scattered evidence of them in the city back to the late 1700s.

[4] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Reintegrazione di possesso’. 16 March 1480 – 16 July 1480, Revò, Sanzenone. The Vicar General of Val di Non and Sole rules that dom. Giorgio of Castel Cles has the right of possession of assets seized from Albertino Albertini of Revò as a solution of a debt owed to him. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1607073. Accessed 8 February 2024.

[5] Revò parish archives, anagraphs, page 73-74 (Revò, 28 July 1624). Nicolò died 19 April 1668, approximately 68 years of age. His brother Lorenzo died on 14 April 1672, approximately 71 years of age. Revò parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number.

[6] Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 34-35.

[7] Revò parish archives, anagraphs, page 79-80 (Revò, 28 July 1624).

[8] Revò parish archives, anagraphs, page 93-94 (Romallo, 4 August 1624). The children’s parents’ names are not recorded in the census, but we can assume they were both deceased.

[9] Giovanni ‘Furlan’ Albertini married Cattarina Giosetta on 17 February 1637. Revò parish records, marriages, volume 1, no page number. In that record, she is said to be ‘living in this parish’, inferring her family came from elsewhere. Indeed this surname is puzzling. There is a couple with the surname ‘Jossetus’ in the census whom I presume are her parents, but she herself is not in the census.

[10] Stefano and Maria married 27 July 1670, and Giovanni and Domenica married 06 Jun 1678 (Revò parish records, marriages, volume 1, no page numbers). Giovanni and Domenica’s first child, Giovanni Battista, was born just two days later.

[11] Stefano was baptised Stefano Simone Albertini on 28 March 1763 (Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 4, page 110). I believe his wife was born Maria Agnese Teresa Martini, born in Revò on 12 January 1761 (Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 4, no page number). I have had to interpolate, as their marriage would have taken place during a gap in the Revò marriage records.

[12] Stefano Pasquale Albertini was born (Cloz parish records, baptisms, volume 3).

[13] He married Margherita Franch on 11 Jun 1842 (Cloz parish records, marriages, volume 4).

[14] Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 5, page 14-15.

[15] The couple married in Riva on 17 June 1826. Riva del Garda parish records, marriages, volume (?), page 84-85.

[16] We find them in Fondo in 1905, then Tione di Trento in 1911, and finally in the city of Trento in 1914. The baptismal record of their first son Alberto Giuseppe Albertini (17 May 1905), tells us Vicenzo’s profession. Fondo parish records, baptisms, volume 9, page 97.

[17] ITALIA.INDETTAGLIO.IT. I Comuni e le Frazioni d’Italia. Motore di ricerca sui cognomi in Trentino-Alto Adige. According to this website, there are about 10 Albertini currently living in Riva. https://italia.indettaglio.it/ita/cognomi/cognomi_trentinoaltoadige.html

[18] Giovanni Andrea was born in Romallo on 10 May 1810 (Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 6, page 31. He was the 4X great-grandson of Giovanni ‘Furlan’ Albertini and Cattarina Giosseta.

[19] Arco parish records, baptisms, volume 18 (page number is cut off in the digital image).

[20] ITALIA.INDETTAGLIO.IT. I Comuni e le Frazioni d’Italia. Motore di ricerca sui cognomi in Trentino-Alto Adige. According to this website, there are about 5 Albertini individuals currently living in Arco. https://italia.indettaglio.it/ita/cognomi/cognomi_trentinoaltoadige.html

[21] GIACOMONI, Fabio. 1991. Carte di Regola e Statuti delle Comunità Rurali Trentine. 3 volume set. Milano: Edizioni Universitarie Jaca, volume 1, page 262.

[22] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez. Fondo: Litotipo Anaune, page 241. 17 May 1492: Archivio Arsio, D3, Carta di Regola 1492: ‘Antonio Albertini Antoniol’.

[23] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Consacrazione e concessione di indulgenza’. 12 August 1500, Castelfondo. Francesco Della Chiesa, Vicar General of Udalrico Liechtenstein, Prince-Bishop of Trento, grants a special indulgence to worshippers who visit and pay alms to the chapel of San Michele on specific feast days. The indulgence agreement was later copied on 5 August 1514 in the presence of maestro calzolaio Nicola Albertini of Brez, rector of the said chapel. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/957147. Accessed 8 February 2024.

[24] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez, page 242. The wording of his citation is a bit confusing, and I am not sure whether this Carta was also for Brez, Castel Bragher or someplace else. The term regolano refers to a man who is on the panel of vicini who enforces local rules that have been laid out in the Carta di Regola.

[25] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez, page 242. 1 December 1548: Arsio Archives, I 18. My translations: Two Marias, daughters of the late Stefano Albertini of Brez. 16 August 1569, Archivio comunale of Brez (ACB), pergamena. Stefano Albertini, regolano of Arsio. 24 July 1580: Archive of Arsio, I 151: Stefano Albertini called ‘Craziberger’.

[26] Lucia, daughter of the last Nicolò Albertini of Brez is cited as the godmother of Antonia, daughter of Antonio Malis of Brez. Arsio e Brez parish records, baptisms, volume 1, no page number. Ruffini (page 242) incorrectly gives the date as 1 Dec 1555.

[27] Arsio e Brez parish records, marriages, volume 1, page 127.

[28] NATI IN TRENTINO. Provincia autonomia di Trento. Database of baptisms registered within the parishes of the Archdiocese of Trento between the years 1815-1923. https://www.natitrentino.mondotrentino.net/.

[29] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez, page 241.

[30] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez, page 241.

[31] Arsio e Brez parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 712-713. There was an older brother of the same name who died at 11 months. There were also three elder sisters. I found a marriage record for one of them (but no children for her), but the Brez records in this era are very erratic when it comes to recording infant/child deaths, I currently know nothing more about the other two besides their dates of birth.

[32] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez, page 234.

[33] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo: (Giovanni Battista Albertini, 1742-1820)’. Studi trentini di scienze storiche. Sezione prima. (ISSN: 0392-0690), 71/3 (1992), page 346.

[34] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo’, page 346.

[35] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez. Fondo: Litotipo Anaune, page 234-235.

[36] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo’, page 347.

[37] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez, page 234-235.

[38] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez, page 234-235.

[39] Maria Flor, wife of Romedio Albertini, died 14 February 1767. Arsio e Brez parish records, deaths, volume 3, no page number.

[40] For a biography of Carlo Antonio Martini de Wasserperg, see my 2022 article ‘The Martini Families of Trentino – Origins, Connections, Nobility, and Challenges of Research. https://trentinogenealogy.com/2022/01/martini-origins-nobility/

[41] His father Romedio died on 2 January 1773. Arsio e Brez parish records, deaths, volume 3, no page number. The record says he was living in the frazione of Traversara at the time.

[42] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez, page 234-235.

[43] See APPENDIX 2 at end of PDF eBook for full list of works as they appear on the University of Innsbruck website.

[44] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez, page 234-235.

[45] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo’, page 361-362.

[46] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo’, page 364.

[47] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez, page 234-235.

[48] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo’, page 367.

[49] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo’, page 377.

[50] Farina (page 377) lists these Trentini among the members of the Innsbruck freemasons at the time: Dr Federico Giuliani, Leopoldo Spaur, Don G.B. Albertini, Giuseppe Baron Ceschi, Giuseppe Conte Guarienti, Felice Baroni Cavalcabò, as well as Francesco de Gummer from Bolzano.

[51] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo’, page 369.

[52] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo’, page 373-374. Also, on page 383, the author says Albertini was granted an annual salary of 300 florins, added to his 900-florin pension.

[53] I’ve had difficulty finding a precise calculation for what this would equal today, but it seems this was near the lower level of the cost of living at the time.

[54] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo’, page 380.

[55] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez, page 234-235.

[56] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo’, page 381.

[57] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo’, page 383.

[58] A ‘beneficiato’ or ‘beneficio’ is a priest who was paid in money or land to celebrate a certain number of Masses. In other words, he was there to perform specific service for the benefit of the parish or a specific patron of that parish.

[59] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo’, page 383.

[60] FARINA, Marcello. 1992. ‘Un prete trentino nella temperie dell’Illuminismo’, page 383.

[61] Arsio e Brez parish records, deaths, volume 3, no page number. My translation.

[62] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Compravendita’. 9 February 1478, Borzago. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/2169610. Accessed 8 February 2024.

[63] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Concessione di vicinato’. 22 January 1484, Caderzone. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1217798. Accessed 8 February 2024.

[64] I did, however, find one Albertino Albertini, son of the late Giovanni, of Pelugo (between Spiazzo and Tione) in a document from 1570. PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Quientanza’. 31 January 1571, Strembo. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1223916. Accessed 8 February 2024.

[65] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Conferma di proclama’. 10 June 1532, Brevine (Tione). Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1223714. Accessed 8 February 2024.

[66] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Redazione di statuti e relativa conferma’. 8 January 1543 – 24 January 1543, Caderzone, Brevine (Tione). Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1217920. Accessed 8 February 2024.

[67] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Conferma di proclama e relativa pubblicazione’. 24 January 1543 – 28 January 1543, Brevine (Tione), Spiazzo. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1223780. Accessed 8 February 2024.

[68] COOPERATIVA ARCOOP (cura). 1989. Comune di Fisto. Inventario dell’archivio (1228-1928) e degli archivi aggregati (1774-1971). Provincia autonoma di Trento. Servizio beni librari e archivistici, page 19. ‘10 May 1563, Nicolò, son of the late Giovanni Albertini Zapani’.

[69] STENICO, P. Remo. 2000. Sacerdoti della Diocesi di Trento dalla sua Esistenza Fino all’Anno 2000. Indice Onomastico, page 9.

[70] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Costituzione d’affitto’. 29 October 1583, Mortaso. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/2129967. Accessed 8 February 2024.

[71] COOPERATIVA ARCOOP (cura). 1989. Comune di Fisto. Inventario dell’archivio (1228-1928) e degli archivi aggregati (1774-1971). Provincia autonoma di Trento. Servizio beni librari e archivistici, page 21. ‘2 August 1605, sindaco Cristoforo Albertini del Fra’.

[72] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Transazione e terminazione’. 2 August 1605, Santa Maria di Campiglio. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/2363126. Accessed 8 February 2024.

[73] I have found several documents written by him between 1621-1624. See ‘Pergamene’ in the RESOURCES at end of this article for details of these.

[74] STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 17.

[75] ITALIA.INDETTAGLIO.IT. I Comuni e le Frazioni d’Italia. Motore di ricerca sui cognomi in Trentino-Alto Adige. https://italia.indettaglio.it/ita/cognomi/cognomi_trentinoaltoadige.html

[76] Tavodo parish records, marriages, volume 2 (?), page 48-49.

[77] Their son Carlo was born 1 November 1635, and daughter Margherita was born 19 May 1640 (Tavodo parish records, baptisms, volume 3, page 116-117 and 198-199, respectively).

[78] Tavodo parish records, baptisms, volume 5, page 238-239.

[79] GIACOMONI, Fabio. 1991. Carte di Regola e Statuti delle Comunità Rurali Trentine. 3 volume set. Milano: Edizioni Universitarie Jaca, volume 3, page 364-375. The Carta is dated 22 May 1751.

[80] ITALIA.INDETTAGLIO.IT. I Comuni e le Frazioni d’Italia. Motore di ricerca sui cognomi in Trentino-Alto Adige. https://italia.indettaglio.it/ita/cognomi/cognomi_trentinoaltoadige.html

[81] Note that records for Piazzola di Rabbi were also kept in San Bernardo prior to 1784.

[82] San Bernardo di Rabbi parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 45-46. In the record itself, the surname is recorded as ‘Berto’, but this is clarified as being Albertini in the baptismal index.

[83] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Costituzione di censo e liberazione da censo’. 20 August 1594, Val di Rabbi. Land use agreement and payment received from the heirs of the late Gioannino Albertini of Somrabbi and others. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/769746. Accessed 8 February 2024.

[84] STENICO, P. Remo. 2000. Sacerdoti della Diocesi di Trento dalla sua Esistenza Fino all’Anno 2000. Indice Onomastico, page 9.

[85] NATI IN TRENTINO. Provincia autonomia di Trento. Database of baptisms registered within the parishes of the Archdiocese of Trento between the years 1815-1923. https://www.natitrentino.mondotrentino.net/.

[86] GIACOMONI, Fabio. 1991. Carte di Regola e Statuti delle Comunità Rurali Trentine. 3 volume set. Milano: Edizioni Universitarie Jaca, volume 2, page 680.

[87] For example, Anna Maria, daughter of Andrea Albertini of Malé and his wife Antonia, was born 30 January 1638. Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 3, page 20.

[88] Their first child, a daughter named Maria Cattarina, was born in San Giacomo on 25 November 1738. San Giacomo parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 85.