Genealogist Lynn Serafinn tackles DNA test ethnicity estimates, showing how and why they might contradict each other and genealogical research. Article 4 of 4.

Today’s article is actually the only one I had planned to write when I first decided to tackle the subject of DNA tests. My original intention was to look at my own ethnicity reports from various companies and show you how their ethnicity estimates stacked up against my own genealogical research.

But as I began writing earlier this year, I realised there were so many underlying factors that needed to be explained before my original ideas would make any sense. Thus, I decided to turn this into a 4-part series, this being the final segment.

If you haven’t yet read articles 1-3 (or you wish to refresh your memory on any of the topics), you can find them at these links:

- ARTICLE 1: In which we examined (TOPIC 1) the different kinds of DNA tests and (TOPIC 2) some basics about autosomal DNA.

- ARTICLE 2: In which we discussed (TOPIC 3) how DNA tests can often point us in a direction, but (usually) cannot give us specific answers about our ancestry or blood relations.

- ARTICLE 3: In which we discussed (TOPIC 4) cultural identity and how it shapes who we believe ourselves to be and (TOPIC 5) what history can tell us about northern Italian ethnicity.

About Today’s Article

In this final article of the series, we’ll at last come to TOPIC 6, which is all about ‘ethnicity reports’ or ‘ethnicity estimates’, i.e. what DNA testing companies like AncestryDNA, 23AndMe, etc. say you ‘are’ in terms of ethnic makeup, primarily based on autosomal DNA testing (if you don’t know what this means, I explain it in Article 1).

It is my observation that DNA ethnicity reports are often a source of confusion – and even emotional upset – for many users, as they are often at odds at what they know or have been told about their own ethnicity. It is my hope this article can help explain why your ethnicity report might contain information that makes no sense to you and share my own thoughts on how we can try to improve the ‘system’ to make these reports more accurate in the future.

TIP: I will be compiling all four articles from this series (editing out the repetition) into a PDF eBook, which I will be offering for FREE to my blog subscribers. If you would like to receive this free eBook, simply subscribe to this blog using the form at the top of this page. If you are reading this on a mobile phone, you can subscribe by sending a blank email to trentinogenealogy@getresponse.net.

Advertising and the Truth About ‘Reference Panels’

I believe there are two primary causes for the confusion many people experience when they get their ethnicity estimate back from their DNA testing company.

One, which I’ve mentioned earlier in this series, is misleading advertising wherein companies explicitly say these tests will tell you who you ARE. As I have previously expressed, people who are descended from immigrant families are especially desirous to know ‘who they are’ because they have been cut off from their ancestral past and feel a strong desire to reconnect.

But misleading advertising gets compounded by a second cause for confusion: a general lack of understanding on the part of consumers about how DNA testing companies create their ethnicity estimates. The truth is:

Ethnicity reports from DNA testing companies do not – and CANNOT – tell you ‘who you ARE’, but only who you are most similar to in COMPARISON to other test takers in their system.

To generate your ethnicity report, DNA testing companies compare your DNA to data gathered from ‘test groups’ of living people (Ancestry calls them a ‘reference panel’) who have known, documented ethnicities. The members of these reference panels are grouped according to ‘ethnicity’ or, in 23AndMe jargon, ‘populations’.

These reference sets provide DNA testing companies with the comparative foundation for their data. And this is the crucial detail that many people don’t seem to understand. The ethnicity reports you receive from DNA tests are not based on some ‘ethnic gene’ sitting in a vault with the name of an ethnic group neatly labelled on it. The reports you receive are COMPARATIVE, not ‘absolute’.

Journalist Ruth Padawer, in her revealingly entitled article in the New York Times, ‘Sigrid Johnson Was Black. A DNA Test Said She Wasn’t’, commented on this topic, saying:

‘Each testing company builds its own reference data set, drawn primarily from its own customers, and each company also creates its own algorithm for assigning heritage. In other words, customers’ results are based on inferences and are merely an estimate, often a very rough one — something many test takers don’t realize and testing companies play down.’ (my emphasis added)

In the same article, Padawer adds:

[The DNA from the test group] ‘becomes the company’s reference data set for that geographic area. When a segment of your DNA closely matches the data for that location, the company assigns you that ancestry. The more segments on your genome that match that genetic pattern, the larger your estimated percentage will be for that ancestry….’

In other words, the DNA companies are comparing your DNA to the information they have in their ‘pool’. Theoretically, the bigger and more ethnically diverse the group, the more accurate the results would be. The smaller the pool, and the fewer ethnic groups represented, the less accurate the results would be.

However, while larger numbers in the sample group ‘theoretically’ mean a better change at accuracy and precision, in practice, it isn’t exactly that simple.

Competition and Lack of Uniformity Between DNA Testing Companies

One reason for this lack of simplicity is the inconsistency with which DNA testing companies label their ethnic populations. The crucial thing to remember is that, despite how they are marketing themselves to us, DNA testing companies are NOT scientific organisations, but commercial competitors. Some of the implications of this are:

- No two companies have the same test people in their reference panels.

- No two companies have the same number of ‘populations’/ethic groups.

- No two companies label their ‘populations’ with the same names.

- No two companies define these populations with the same geographic boundaries.

Thus, the accuracy of your ethnicity report depends COMPLETELY upon who the test company is comparing you to. This means:

Because ethnicity reports are comparative, the results you will receive from one DNA testing company is likely to be different (sometimes radically) from what you receive from another.

Ethnic Populations Represented in DNA Test Groups

In their 2018 white paper on ethnicity estimates, AncestryDNA explained how they chose the people who formulated their DNA reference panels, which (in 2018) contained 16,638 samples, broken into 43 overlapping global regions – a big leap up from their previous DNA test group, which had 3,000 samples, and represented only 26 global regions.

While they say they drew upon samples from the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) and the 1000 Genomes Project, they clarified, ‘it was not possible to confirm family trees’ for people from these groups. I take this to mean the ethnic groupings were not based on ‘documented’ (i.e. genealogical) evidence.

They then explained that they ‘examined samples from a proprietary AncestryDNA reference collection as well as AncestryDNA samples from customers’, most of whom were selected because their online trees ‘confirmed that they had a long family history in a particular region or within a particular group.’ They said their aim was to use only ‘single-origin individuals’ for their reference panel, i.e. people who are known to be ‘100% of a single ethnicity’, based upon documentation (again, genealogical evidence).

As a genealogist, this in itself is interesting to me, as I believe many people have the mistaken impression that DNA exists as a science independent of genealogy (something I discussed in Article 2). These statements by AncestryDNA confirm they can only work when used hand-in-hand.

How Far Back in Time Do Ethnicity Reports Reflect?

But what exactly do AncestryDNA mean by ‘long family history’?

In that same white paper, AncestryDNA express the challenges of finding suitable candidates with well-documented ancestry. They explain:

‘When asked to trace familial origins, most people can only reliably go back one to five generations, making it difficult to find individuals with knowledge about more distant ancestry. This is because as we go back in time, historical records become sparse, and the number of ancestors we have to follow doubles with each generation.’

‘Five generations back’ is great-great-great-grandparents (3X GGP). My 3X GGPs were born in the late 1700s, less than 250 years ago.

Well, I don’t know who they mean by ‘most people’, but most people I know who are serious about genealogy can trace their roots back further than that. A span of five generations isn’t exactly what I would call ‘deep history’.

But, alarmingly (to me, anyway), they go on to say:

‘Ideally, we’d use people with all of their grandparents from the same country, but due to low numbers for some countries we sometimes use parents or even the customer’s birth location.’ (my emphasis added)

Seriously? These are their criteria for their reference groups?

I myself have traced my own Trentino ancestry back to the early 1400s (and some lines beyond that, via additional historical references), and my Cimbri/Veneto ancestry to the mid-1600s. Moreover, I’ve traced the lineages of many of my Trentino clients back to the 1500s, as we Trentini are fortunate enough to have access to our parish records in digital format at the Diocesan Archives of Trento, plus a wealth of other archives throughout the province.

Given the disparity between the genealogical evidence and what Ancestry DNA (and presumably other companies) are currently using as criteria for comparison, how could their ethnicity estimates possibly represent an accurate ethnic profile of anyone who has traced his/her ancestry back several hundred years?

Again, the facts hardly reflect the promises made in their marketing campaigns.

Under-Represented Ethnicity Groups

AncestryDNA admit that some ethnic groups are less well represented in the database, and that these can cause anomalies in their reporting. They say:

‘For example, individuals from Spain might get some assignments to France and Portugal, while individuals from Norway and Sweden might get some level of assignment to each other.’

I might add to this that a large number of people whose ancestors came from Trentino and other parts of northern Italy are now being labelled ‘French’ (as we’ll look at in a few minutes).

But apart from under-represented ethnic groups, the BIG issue for me is that geography on its own – and especially the name of a COUNTRY – does not define ethnicity. ‘Nations’ have little to do with ethnicity. The Americas and Australia surely give testament to that. And the fluctuating boundaries throughout the history of the Italian peninsula – including Trentino – also demonstrate this. Any given geographic region can also contain a rich blend of ethnic groups. For example, the Cimbri people (who are of Germanic descent) have lived in many communities in northern Italy for hundreds of years. But what are the chances someone of Cimbri descent will be labelled as such in a DNA test?

Until such ethnic groups are adequately represented in DNA test groups, the answer is ‘virtually nil’.

Sadly…

Ethnicity reports from autosomal DNA tests will frequently CONTRADICT what you know about your own ancestry via genealogical research – especially if your ethnic population is not represented (or under-represented) in their reference panels.

If an ‘ethnic population’ is absent, under-represented, or defined too broadly within a given reference panel, it is unlikely that DNA test will identify these groups with precision (if at all).

In fairness to Ancestry, on page 33 of their white paper, they add some notes about what they call their ‘Ethnicity Improvement Cycle’:

‘Currently, we are working to further expand our global reference panel for future ethnicity updates. We have already begun genotyping and analyzing samples for a future update which we expect will provide even better estimates. We have also begun a new diversity initiative to gather DNA samples from underrepresented regions around the world in order to expand the number of regions we can report back to customers.’

CASE STUDY: My Ethnicity Reports

So how does someone like me show up in commercial DNA ethnicity reports? First, I need to explain what I KNOW about my own ancestry, so you can see the reports in context:

- My mother was (to the best of my knowledge) of 100% Irish background, with ancestors primarily from County Cork and Kerry. I have documented evidence for most of her family only back to the early 1800s, as many records for their towns/parishes are missing.

- My father and both of his parents came from Trentino, and I have traced nearly all his ancestry there (hundreds of ancestral lines) back to the 1400s.

- HOWEVER, my father’s mother’s mother (one of my great-grandmothers) came from Badia Calavena near Verona in Veneto, known to be an ancient Cimbri community. I have traced nearly all her ancestry there back the early 1600s.

Knowing this about me, you would EXPECT my ethnicity report to look something like this:

- 50% Irish

- 50% Northern Italian OR some other combination of ethnicities (central and northern Europe, for example), depending on how they divide and label things.

Let’s see how the DNA reports reflect the genealogical data (or not).

EXAMPLE 1: AncestryDNA

As AncestryDNA recently undated their algorithm, I’d like to show a ‘before and after’ comparing their old report to their revised one.

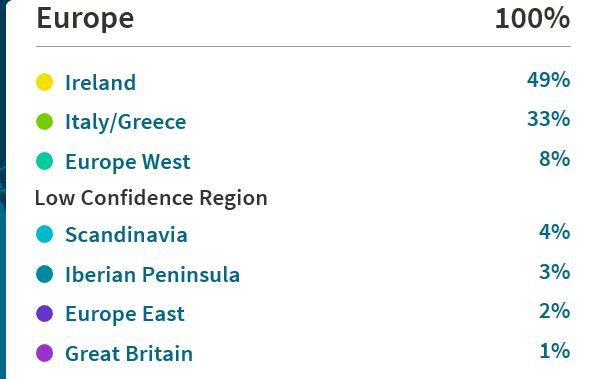

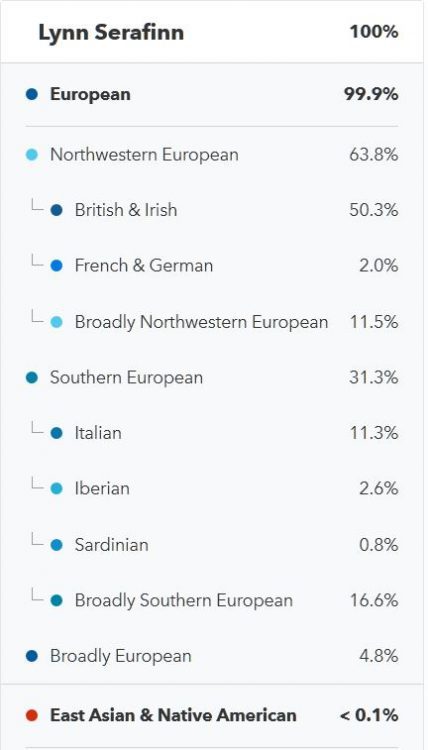

AncestryDNA’s OLD Ethnicity Report

Here is a snapshot of my estimated overall ethnicity, taken from the ethnicity report I received from AncestryDNA a few years ago:

This report shows 49% Irish, which is close enough to the 50% I would have expected for my mother’s side. I assumed the 1% Great Britain probably made up the remainder.

So, if that was the case, it meant the other mishmash of ethnicities represented my dad. Back then, I tried to make sense of these baffling figures.

Let’s look at the reference to Scandinavia, for example. If I actually DID have 4% Scandinavian ancestry, and that percentage referred to a single ancestor, it would have to mean that ancestor was no further back than one of my 3X GGPs. This is because, unlike mitochondrial or Y-DNA, autosomal DNA gets cut by AT LEAST half with each generation. I say ‘by at least half’ because, while we inherit 50% of our DNA from each of our parents, the percentage of DNA we inherit from earlier ancestors becomes less mathematically predictable with every passing generation.

But the thing is, I happen to know my Trentino-born father’s ancestry, and I have traced ALL of his lines hundreds of years past the point of 3X GGPs. In fact, I have been transcribing ALL the parish records for my father’s parish of origin and connected all the families onto one tree. After tracing over 23,000 people so far, every single one of these people WITHOUT EXCEPTION came from Trentino or adjacent regions/provinces like Veneto, Verona, Lombardia or Alto-Adige/Bolzano – for the past five to eight centuries.

Nope. Not a Viking in sight.

So, Am I Really Scandinavian?

So, if I knew for SURE I don’t have any (recent) Scandinavian ancestors, the question was still how that figure of 4% Swedish got into my ethnicity report.

I started hypothesising that it might reflect very ANCIENT Scandinavian ancestry via the LONGOBARDS (whom I discuss in Article 3), whom I knew inhabited my father’s homeland of Val Giudicarie in the Middle Ages.

My hypothesis expanded as I started to study how autosomal DNA is transmitted throughout the centuries. While our inherited autosomal DNA from each individual ancestor decreases by half every generation, something peculiar – and quite interesting – can happen to our autosomal DNA over long periods of time.

Back in Article 1, I talked about ‘pedigree collapses’ and ‘endogamy’, wherein one ancestor (or a pair of ancestors) is related to us via more than one line. Just as this phenomenon can create ‘false positives’ for close living DNA matches, it can ALSO show up as a possibly misleading finding in our ethnicity report. Why? Because the further back you go in time, there is an ever-increasing chance that EVERYONE (especially those living within a given radius) is your ancestor, and probably in multiple ways. This means that, when you get to, say, 1,200 years or more, that probability of being related to ANYONE alive at the time increases to pretty much 100% certainty.

TIP: This idea is more fully explained in an excellent article called: ‘Autosomal DNA, Ancient Ancestors, Ethnicity and the Dandelion’, which you can find at https://dna-explained.com/2013/08/05/autosomal-dna-ancient-ancestors-ethnicity-and-the-dandelion/.

With enthusiasm, I spent a lot of time and energy developing this ‘hypothesis’ of my ancient Longobard ancestry. But then, it all came to a crashing halt in September 2018.

Bye Bye Scandinavia

Well, apparently, all my theories about ancient Longobard roots were simply a waste of time because, when AncestryDNA revealed their new ethnicity reports late last year, and every drop of my Scandinavian ancestry vanished without explanation.

‘Word on the street’ was that Ancestry had realised they had gotten it just plain wrong. In fact, after their new algorithm was announced, I did a bit of digging and found more than one blog article from 2012-13 in which AncestryDNA was criticised for the fact that almost everyone’s DNA results showed Scandinavian heritage!

OK, admittedly they did say that part of the report was ‘low confidence’, but surely this quirk was downplayed to their customers.

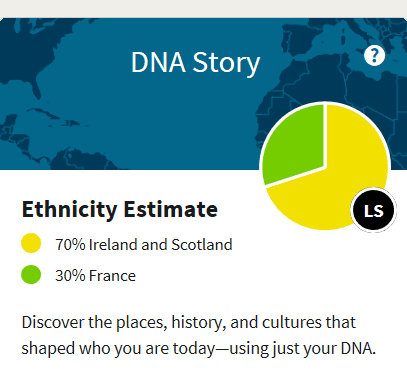

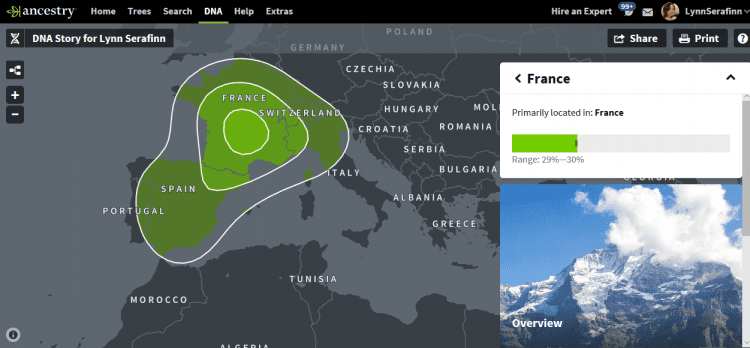

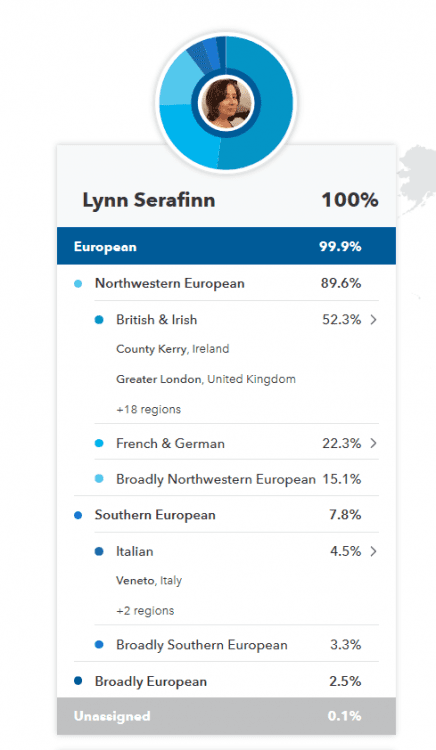

AncestryDNA’s NEW Ethnicity Report

So, aside from my vanishing Vikings, what is different in my new, ‘improved’ ethnicity report? Below is a screenshot of what currently greets me on my AncestryDNA landing page. Imagine my bewilderment when I first saw this:

70% Irish? How is that even possible? That would attribute at least 20% of my paternal ancestry to Ireland – meaning my dad was about half Irish, which 500+ years of documented evidence demonstrates he was certainly NOT.

And 30% FRENCH? That would mean my father was more than half French (and the other half presumably Irish).

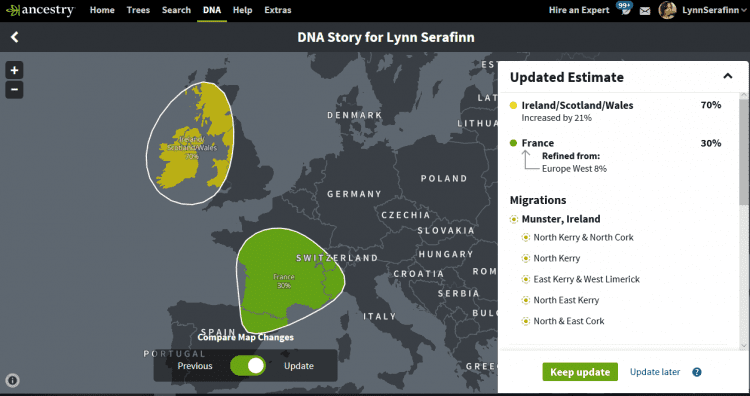

I took a closer look at the ‘updated estimate’ and saw this map of their ethnicity regions:

Ironically, the detailed breakdown for Ireland, is much MORE accurate and detailed than my earlier report, showing my Irish ancestors were primarily from Munster (which is indeed correct).

But 70% Irish and 30% French? Seriously?

Frankly, when I saw this, I found myself pretty riled. I couldn’t understand how any company could advertise so aggressively, make so many promises (and so much money) and deliver product that was just so…ODD.

What Does Ancestry DNA Mean By ‘French’?

Trying to make sense of their new ‘labels’, I wanted to understand just what Ancestry meant by ‘French’. So, I expanded their report to see this more detailed map:

We can see that Ancestry’s ‘French’ designation actually encompasses many other countries, including Spain, parts of Portugal, Switzerland, Belgium, Austria – and northern Italy.

That’s a lot of different countries, and only two of them (apart from France itself) even speak French. Moreover, if you read it carefully, it indicates the actual country of ‘France’, comprises less than 1/3 of the total area of the region being labelled as ‘France’.

So, I’ve got to ask: whose bright idea was it to label all these DIVERSE ethnicities as ‘French’?

The ‘French’ (DNA) Revolution

AncestryDNA might see ‘French’ as an arbitrary designation to label the place (not the people) where THEY have found the highest concentration of this genetic data, but the fact is, this label is anything but arbitrary to their customers.

The public reaction to these new labels became abundantly clear when I visited some of my genealogy groups on Facebook, and read dozens (if not hundreds) of impassioned comments. In fact, people are STILL commenting about them. Here are a few representative highlights:

- READER 1: I just realized that I received 37% French in the new update, where none existed before. This would account for 2/3 of my mother’s admix, a first-generation northern Italian American, genetic makeup. Even if there was a previously unknown French ancestor in the mix and the paper trail indicates none, for my mother to be 75% French is ridiculous. (My father is of 100% German heritage, a mix of regions, which is accounted for). #BonjourNo

- READER 2: Something is definitely not right. My dad is half northern Italian and half Polish, yet the “updated results” show that he’s 93% Eastern European/Russian and 7% Western European. That cannot be right especially when my updated results show 2% Sardinian and my mother’s side is all German.

- READER 3: I just updated! I’m French??? My mother’s family is from Filecchio near Barga near Lucca. My cousin traced them back to 1400-1500. This is northern Italy, not France. If anything, it is more Celtic. My father was 1/2 Irish, 1/2 English (OK, maybe some Scot) My Irish increased, English vastly increased, and Greece popped in the picture. Italy was down (Ancestry assume “Italy” means SOUTHERN Italy). No longer Middle Eastern or other traces. Sure, I took French in high school and I like France, but I know my Italian heritage, and it is not French. Makes me doubt the whole Ancestry DNA analysis…

Clearly, AncestryDNA are upsetting many of their customers. By using a ‘blanket label’ of ‘French’ for northern Italians and other European ethnic groups (even when they have a map explaining what they mean by it):

AncestryDNA are challenging (if not invalidating) the cultural identities of many of their users.

When ‘The French Revolution’ hit the Facebook groups, many people who have purchased these tests in good faith seemed to want to find a reason to believe the new label, despite the fact it went against the grain of what they believed (or KNEW) about their own ethnic origins. Seemingly desperate to make sense of it all, some even suggested our ‘Frenchness’ may have been due to the Napoleonic era. To such musings, I pointed out that, as Napoleon was around only 200 years ago, for 18th century France to change our ethnic identity to such a degree, every one of our Trentino female ancestors would have to have been impregnated by a French soldier roughly between 1805-1815 (which I assure you didn’t happen). This is how much people wanted to trust Ancestry, and to give them the benefit of the doubt.

And when people TRUST you that much, you have an immense MORAL RESPONSIBILTY. But, from my angle, AncestryDNA’s new labelling seems is definitely insensitive, and verging on morally irresponsible.

I do not believe AncestryDNA truly understand the EMOTIONAL impact of their decision, nor the underlying desires of their users. I would be willing to bet a high percentage of their customers are American descendants of European immigrants, who are trying to reconnect to a lost part of themselves. And, as I expressed in Article 3, ‘Ethnicity Vs. Cultural Identity. Trentino, Tyrolean, Italian?’, many such people are ALREADY unsure – and often confused – about their own ethnic identity. For them, labels are far from arbitrary; they are VERY important.

Perhaps had AncestryDNA called this group something like ‘Alpine European’, it would probably have been more emotionally acceptable (and respectful) to all those who fall into this category.

Perhaps they’ll read this and reflect on what they’ve actually taken upon themselves.

EXAMPLE 2: 23AndMe Ethnicity Report

Looking at 23AndMe, here is what they told me back when I first bought their test in 2015:

Once again, the Irish side of my ethnicity is pretty accurate, and my dad’s ancestry is a hotchpotch of ethnicities, including a rather intriguing ‘low confidence’ referent to what they said was Yakut in Siberia (‘East Asian’ in chart above).

Their new 2019 stats are interesting, as they SEEM to be trying to ‘fine tune’ different regions at a more granular level:

As you see, they’ve assigned subregions for their ‘British & Irish’ and ‘Italian’ categories. They haven’t yet defined the regions include under ‘French & German’ (they say they’re working on it), and the ‘Broadly’ northwestern and southern European are indeed ‘broad’ designations.

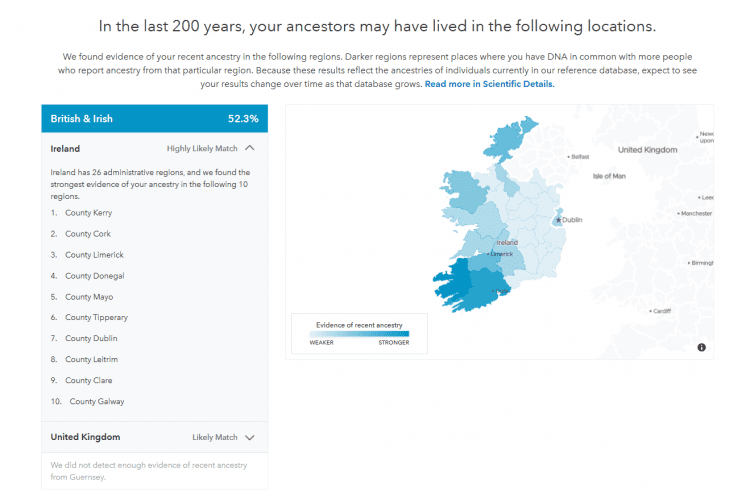

Here’s a look at the Irish subregions, reflecting my mom’s Irish ancestry:

The darker areas (especially Kerry, Cork and Limerick), they say, are those which my ancestors ‘may have lived’ in the last 200 years. In this case, their estimate CONFIRMS what I already know about my mother’s family.

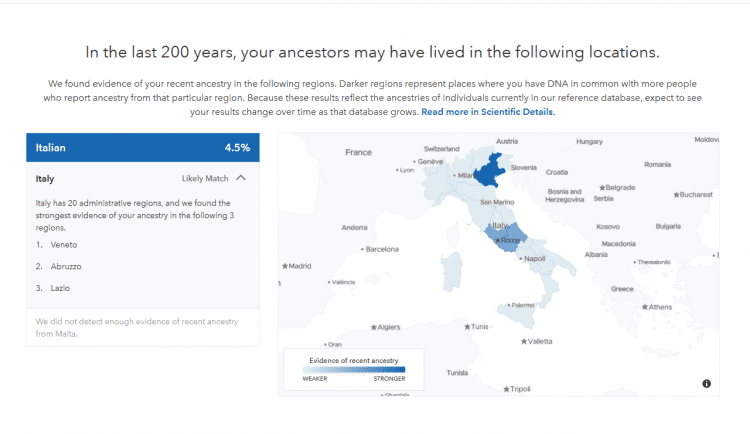

Now, here’s the map of the regions they’ve mapped out for my ‘Italian’ ancestry, which, they say, comprises 4.5% of my DNA:

What is interesting is it shows the strongest ‘likelihood’ of my ancestors coming from Veneto. This, I would ASSUME comes via my great-grandmother, who came from Verona area, and whose ancestry I have traced back about 400 years in that area. My own genealogical research has shown me that Abruzzo and Lazio are definitely not in the picture (at least not in the last 500 years). While a great-grandparent can contribute as much as 12.5% of your total DNA, it isn’t necessarily going to show up that high, so it’s not completely contrary to my genealogical research to see a lower percentage. Besides, I know her family came from a Cimbri community, which means some of her DNA could get flagged up as ‘German’ rather than ‘Italian’.

But if we accept this ‘Italian’ percentage as belonging to my Veronese great-grandmother, and the Irish as belonging to my Irish mother, what about my dad’s Trentino ancestry? What’s THAT mess about?

According to their estimates, 43.2% of ‘me’ is so broad a to be practically useless, except to say I am some sort of ‘European’.

What can I possibly learn from such ambiguity?

I’ll tell you what it tells me. It tells me they have a LOT of people of Irish descent in the 23AndMe database. That’s why the information about my mother’s side is getting more accurate.

It also tells me they have a growing pool of Italians in their database, but possibly NOBODY from Trentino. That is why the ethnicity reports for my father’s side is still a long way from showing anything useful.

So, for now, I can only take from 23AndMe what it gives me, rather than trying to make sense of what it cannot. I feel encouraged by they increased ‘granularity’, and hope to see more detail in the future. And, for now, I’m not going to speculate what their ‘French & German’ category means, as they say they are still expanding it.

EXAMPLE 3: MyHeritageDNA

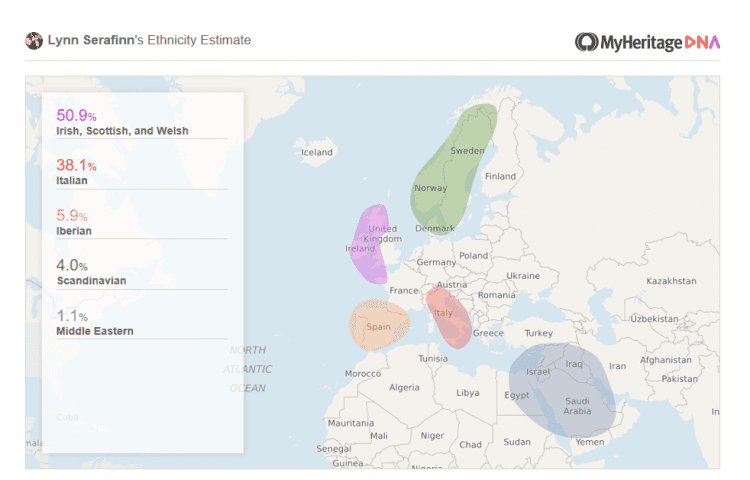

I haven’t taken a DNA test directly from MyHeritage; rather, I uploaded my ‘raw’ DNA from 23AndMe to their website, when they offered this as a free option a few years ago. Here is their ethnicity breakdown:

As you can see, my mom’s DNA is still showing up as 50% Irish (this time lumped in with Scottish and Welsh), and my dad’s side shows yet another odd potpourri of ethnicities, albeit this time with more emphasis on ‘Italy’.

I won’t say more about this particular report, but I thought you might find it interesting to compare it to the others.

EXAMPLE 4: CRI Genetics

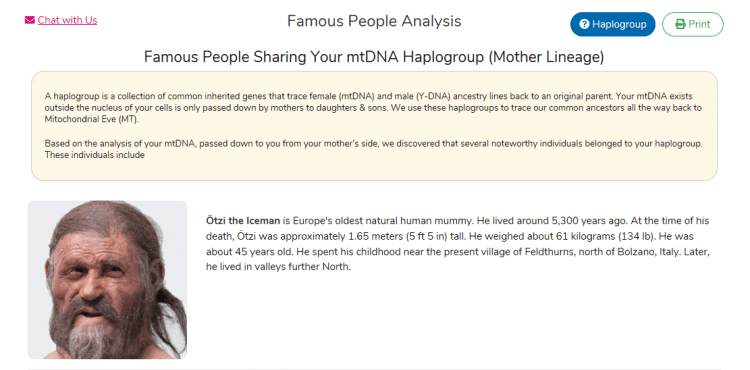

And finally, here are the results of my tests from a company called CRI Genetics, who tout themselves as being ‘genetic scientists’ rather than big business. I ordered both an autosomal AND mitochondrial DNA test from them, with high hopes these ‘scientists’ would reveal more accurate results than their competitors. On a lark, I also bought their ‘Famous People Analysis’, which allegedly identifies some famous people who share your DNA.

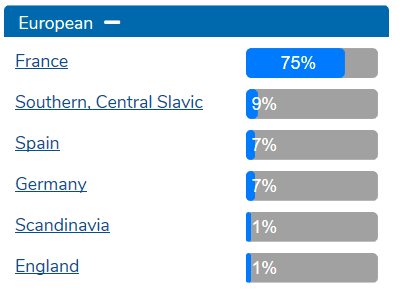

But then I got the results. And let me tell you, I think they are the most bizarre I’ve received to date. Here are the results from their autosomal test:

According to them, not only is my father ‘French’, but so is my Irish mother! In fact, according to them, I’m 75% French.

Their mitochondrial test (for which I paid an additional fee) was certifiably underwhelming. If fact, it was less informative than what was included in 23AndMe’s autosomal test, where they identified my maternal haplogroup.

And their ‘Famous People Analysis’? A complete joke. While claiming I am related to modern-day people like actors Meryl Streep and Jake and Maggie Gyllenhaal, they also claim I am related to the 5000-year-old mummy knowns as ‘Ötzi the Iceman’ via my mother’s mtDNA:

There’s just ONE teensy problem with this:

Ötzi’s maternal haplogroup is currently believed to have DIED OUT a long time ago. His mitochondrial DNA does not fit into any known subclades from modern Europe.

Now, the thing about Ötzi is that just about anyone of European descent IS most likely related to him (but not necessarily a descendant), by simple statistics. But actually saying I am related to him via mitochondrial DNA is just plan LYING.

To rub salt into an already festering DNA wound, CRI Genetics has something they call an ‘Advanced Ancestry Timeline’. According to them, one of my ancestors from around the year 1850 was from Sri Lanka, another from Peru around 1625, and yet another from Gujarat, India in 750 A.D.! Of these claims, they say ‘Statistically we determined this to be 99% accurate.’

Science? More like mythology. And definitely a huge rip-off.

How We Can Improve the Future of DNA Testing

I think you might have deduced by now, that I feel it is important NOT to put too much stock in – or get too hung up about – an ethnicity report from ANY company, including those I have not mentioned in this article. Always remember that the results you are getting are all COMPARATIVE based solely on the size of their database, and the picture they paint of your ethnicity is on an ever-expanding canvas.

But please don’t leave with the impression I am suggesting you should NOT do a DNA test, or that I have given up hope on ‘big’ companies like AncestryDNA. Actually, I believe those of us who are passionate about our family history can do much to help IMPROVE the accuracy and precision of ethnicity profiles in these larger companies.

How?

By providing DNA testing companies with more data from currently under-represented ethnic regions.

In other words, TAKE a DNA test, not so much to discover information, but to provide information that can (hopefully) improve the accuracy and precision of genetic science.

Surely Trentino is one such under-represented region, but I am sure many of you reading this can identify hundreds of others. As a genealogist, I would love to present a ‘Trentino contingency’ to both AncestryDNA and 23AndMe, so we are finally represented in their test groups.

Despite my extensive genealogical research into my own ancestry, I might not be the ideal test subject, due to having a ‘mixed’ ethnicity within recent generations. But those of you who are Trentino on both your paternal and maternal sides, and who have well documented family history, would be excellent candidates. If you fall into this category, I would love to hear from you.

Of course, if you are of Trentino descent but you have not yet researched your family very far, you might consider hiring me to help you in this regard (more information about this is below).

In either case, I invite you to connect with via the Contact form on this site.

Closing Thoughts

I hope this series on DNA testing has helped you better understand what DNA tests are, how genealogy works in tandem with DNA testing, and how ‘ethnicity estimates’ are generated.

Equally, I hope these articles have encouraged you to look more deeply into your own cultural identity, and increased your confidence as you try to make sense of your DNA test results — even when they seem to make NO sense at all.

Many thanks to all of you who have read this entire series, especially those who have left comments on this site. It is truly encouraging to me when I hear your feedback and learn from your experiences.

Now that the series is complete, I will be compiling the articles (editing out the repetition) into a PDF eBook, which I will be offering for FREE to my blog subscribers. If you would like to receive this free eBook, all you have to do is subscribe to this blog using the form at the top of this page. If you are reading this on a mobile phone, you can subscribe by sending a blank email to trentinogenealogy@getresponse.net.

Please be patient, as it will take a month or so to edit the articles and put them into the eBook format.

I look forward to your comments. Please feel free to share your own research discoveries in the comments box below.

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

P.S. My next trip to Trento is coming up from June 29th to July 27th 2019.

If are considering asking me to do some research for you while I am there, please first read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Subscribe to receive all upcoming articles from

Trentino Genealogy!

Desktop viewers can subscribe using the form

at the right side at the top of your screen.

If you are viewing on a mobile device and cannot see the form,

you can subscribe by sending a blank email to trentinogenealogy@getresponse.net.

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

References

AncestryDNA Science team. 2018. ‘Ethnicity Estimate 2018 White Paper’. Accessed 13 May 2019 from https://www.ancestrycdn.com/dna/static/pdf/whitepapers/WhitePaper_2018_1130_update.pdf

Estes, Roberta. 2013. ‘Ancient Ancestors, Ethnicity and the Dandelion’. Accessed 13 May 2019 from the DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy blog at https://dna-explained.com/2013/08/05/autosomal-dna-ancient-ancestors-ethnicity-and-the-dandelion/.

Genovate Laboraties. 2016. ‘Compare Your DNA to Ötzi the Iceman – a 5000-year-old mummy’. Accessed 13 May from https://www.dnainthenews.com/human-history/otzi-iceman/

Padawer, Ruth. 2018 (19 Nov). ‘Sigrid Johnson Was Black. A DNA Test Said She Wasn’t’. New York Times online. Accessed 13 May 2019 from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/19/magazine/dna-test-black-family.html

Wikipedia. 2019. Ötzi the Iceman. Accessed 13 May from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_haplogroups_of_historic_people#Ötzi_the_Iceman