Genealogist Lynn Serafinn shares a story from her own Trentino family history, and proposes we shed a different light on what it means to be a ‘hero’.

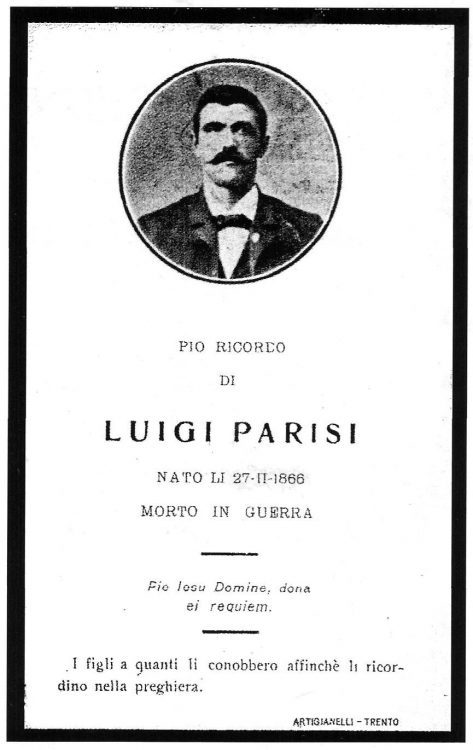

In honour of Memorial Day in the US, I wanted to share some photos and the story of a member of my family who fell during World War I: LUIGI GIUSEPPE PARISI (1866-1917), the beloved younger brother of my great-grandmother Europa Parisi (she was the mother of my grandfather, Luigi Pietro Serafini).

But here’s the catch: Luigi Giuseppe died while fighting with the Austro-Hungarian army – the proclaimed ‘enemy’ of the US during that war. And Luigi’s story is even more complicated than that, as you’ll see as you read this article.

Luigi the Trailblazer

Luigi Parisi was born on 27 February 1866 in Duvredo, a small frazione (hamlet) in the rural parish of Santa Croce del Bleggio in Val Giudicarie in Trentino. My father was born in the same frazione. Although he was not my ancestor, I feel a strong debt to Luigi, as he played a huge role in the destiny of our family, as well as the Trentini community.

He was the first in our family to travel to America in search of a better life, after devastatingly hard economic times had fallen on his ancestral homelands, leaving his life as an Alpine farmer to work in the coal mines of Brockwayville (now Brockway) and Brandy Camp Pennsylvania. Regarding Brandy Camp, on page 231 of the book A Courageous People from the Dolomites (1981), author Father Bonifacio Bolognani says:

‘The first settler in Brandy Camp as a Parisi from Santa Croce del Bleggio. He is also the father of the present pastor of Santa Croce, Father Leone Parisi.’

Although he does not give the first name of said ‘Parisi’, the author is referring to Luigi, whose son Leone served as pastor of Santa Croce del Bleggio for many years. The presence of the Bleggiani in Brandy Camp had a permanent affect on the local culture. The clearest example is in the choice to call their local church ‘Holy Cross’ (which is what ‘Santa Croce’ means), to honour the memory of their home parish.

Families Separated By An Ocean

Many people mistakenly assume our ancestors never went back once they had left the ‘old country’, but many (if not most) of the early Trentini immigrants had no intention of staying permanently in the US. Luigi was no exception to this. Gleaning what I can from immigration records, Luigi seems to have gone back and forth to America four times, crossing the ocean eight times between 1890 and 1911. (His young nephew Emmanuele Giuseppe would eventually make the trip 12 times before he ‘retired’ with his Trentino family at the age of 51).

During those years, Luigi managed to father 10 children (only six of whom survived to adulthood), with two wives in between his stays in the US. The mother of his first five children was Emma Bleggi, who died in 1898 at the young age of 34 from tuberculosis – a disease that claimed the lives of so many young adults in their 20s and 30s. After Emma passed away, Luigi married Emma’s younger sister, Ottavia. He and Ottavia called their first daughter ‘Emma’ to honour the memory of their late wife/sister. Aside from Emma, they had four other children, one of whom died in infancy.

Mentor and Guardian of the Next Generation

In 1906, my grandfather, Luigi Pietro Serafini, who was then 18 years old, followed in his uncle’s footsteps and joined him to work in the mines. Later, his younger brother Angelo Serafini would join them, along with an equally young cousin named Emmanuele Giuseppe Serafini. Their uncle Luigi was both their mentor and their guardian as they adapted to this strange new land and dangerous new occupation.

Around 1910, leaving my grandfather in charge of the younger boys, Luigi made a short trip back home to Duvredo. He made his fourth (and what would be his final) trip to the US in November 1911, a few months after the birth of his last child.

According to Aldo, the 98-year-old son of my grandfather’s brother Angelo, my grandfather and the other younger men were enjoying the ‘freedom’ of their young bachelor lives in Pennsylvania. But Luigi was no longer a young man, and was surely tiring of his trans-Atlantic journeys and harsh existence in the mines. He also felt a sense of responsibility for the younger men. So, early in 1914, Luigi, who was now nearing 50 years old, told his nephews that he missed his wife and children and wanted to return to Trentino.

He also advised that it was about time my grandfather, now 26 years old, went home to find a bride.

The young men did as their uncle bid, and returned with him to Trentino, albeit half-heartedly. That April of 1914, my grandfather did indeed get married to my grandmother Maria Onorati. His brother Angelo and cousin Emmanuele Giuseppe, being a several years younger, decided to wait a few years before settling down.

The Great War Arrives

But as we all know, later in 1914, the world was shaken up when the Great War – which we now call World War 1 – began that summer. In those days, Trentino was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; for many centuries before it fell under the banner of the Holy Roman Empire, which was essentially by Germanic/Austrian. However, most Trentini (including most of my own family) had Italian names and spoke Italianate dialects.

When the war first broke out, Italy wanted to remain neutral. But later, they joined the Allies in 1915. One of their main reasons for doing so was because the Allies promised to give Italy the Austrian ruled provinces of Trentino and Alto-Adige if they won the war.

The Great Political Divide

All of these factors meant that there were many varying loyalties in the region: many Trentini wanted to become part of Italy, while many others wanted to remain part of Austria. Sometimes divided loyalties could even be found within the same family. For example, my great-uncle Luigi Parisi is reported to have been pro-Italy, while both of my grandparents were very much pro-Austria.

While none of us can possibly know what he truly felt, Luigi’s purported political leanings are mentioned on page 100 of the book Ricordando by Luigi Bailo, who says Luigi Parisi was reputed to be a friend and political sympathiser of the priest don Giovanni Battisti Lenzi.

Don Lenzi was labelled an ‘irridentista’ (an advocate for the unification of Italy) by the Austrian government and was exiled from Trentino by the Austrian government during the war. So, if Bailo is correct and Luigi Parisi was also pro-unification, does it mean his being drafted into the Austro-Hungarian army compelled him to fight on ‘the wrong side’ from his perspective?

Sadly, although pardoned in 1917, don Lenzi died in Innsbruck before he could return to his homeland. His remains were later returned to Santa Croce, where there is a memorial to him outside the parish church.

Trentini Soldiers in Russia

Because Trentino was so split in loyalty, the Austrian government feared that if they sent Trentini soldiers to fight on the Western front, they would ‘turn coat’ and defect to the Italian army. So, instead, most of the Trentini men – including my grandfather, his brother Angelo and his uncle Luigi Parisi – were sent to the Eastern front to fight in Russia. The battles there were notoriously brutal, as was the bitter weather and harsh living conditions.

My grandfather and his brother spent a significant period of time in Siberia as prisoners of war (1915-1917), along with an astonishing 2.3 million other Austro-Hungarian troops, most of whom were captured after the battle of Galicia. The majority of those who managed to survive ended up WALKING home across Europe, after the Russian revolution caused their entire infrastructure to collapse, resulting in the release of the POWs.

Luigi Parisi: ‘Missing in Russia’

But their uncle Luigi Parisi was still fighting on the Eastern front in 1917. Then, one day he and his regiment were crossing a river under fire. When they took roll call on the other side, Luigi never replied.

At age 51, Luigi Parisi had vanished and was never seen again. His military record says ‘disperso in Russia’ (missing in Russia). He is listed in the Tyrolean ‘honour roll’ in Innsbruck as having fallen in battle, as he was presumed dead.

A photo of his memorial card appears on page 100 of Ricordando:

The Family Left Behind

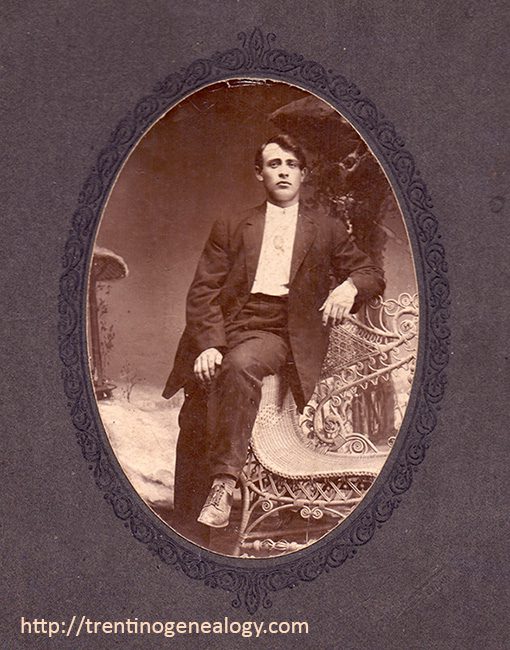

As mentioned earlier, one of Luigi Parisi’s six children, a boy named Leone (who was only 7 years old when his father fell in the war), grew up to become the parish priest of Santa Croce, known to all as ‘don Leone’.

Until his death in 1986, don Leone was highly influential and widely loved in the community and played a role in the lives of many people in the parish. Below is a photo of don Leone as a young priest, with many members of his extended Parisi-Bleggi family. His mother, the widowed Ottavia Bleggio, is the elderly lady seated behind and to his right.

After the war, my grandfather and his brother returned to America. A few years later, they were followed by their wives and children, including my late father Romeo Fedele Serafini (Ralph Raymond Serafinn). Between them, these two brothers went on to have 8 children and dozens of grandchildren (and now a new generation of great-grandchildren), who all grew up in America.

I truly doubt these young men and their families could have settled as quickly and successfully as they did had they not been mentored by their late uncle Luigi before the war. I doubt I would even be alive had he not blazed the trail for the rest of us back in the late 19th Century.

What Do We Mean By ‘Hero’?

While his country has dubbed him ‘hero’ because he fell in battle, I see my great-grand uncle Luigi Parisi through a different lens.

Politics do not define him to me. It doesn’t matter to me that he fought for the ‘enemy’ of the US, or that he might have secretly been ‘an enemy’ of the Austrian empire, or that he might have been ‘pro’ Italy. None of that matters to me.

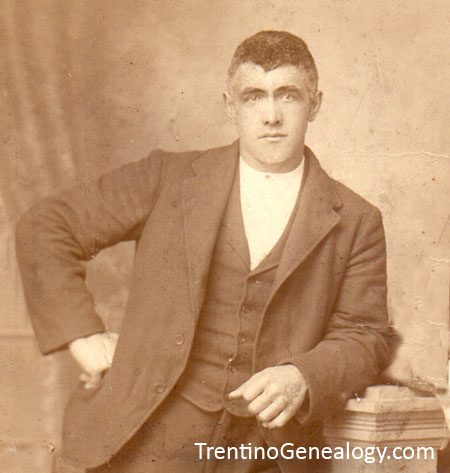

To me, he is a hero because he was a guiding light for his family and his community – on BOTH side of the Atlantic. His story and photos reveal an intensity of character that was demonstrated by his actions throughout life. I know I owe my life to him, although I never met him.

My personal belief is:

If everyone could embrace their ancestors and family members from the past as ‘heroes’ in this way – without any prejudice or political bias – the world will become a much more loving and forgiving place.

I encourage and invite you to remember and celebrate all of your family heroes, whatever ‘side’ they might have been on. We owe so much to all of them.

Please feel free to share your own ‘family hero stories’ in the comments box below.

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

27 May 2019

P.S. My next trip to Trento is coming up from June 29th to July 27th 2019. My client roster is currently FULL for that trip. But if you would like to ask me to do some research for you on one of my future trips, please first read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

P.P.S.: I am still working on the edits for the PDF eBook on DNA tests, which I will be offering for FREE to my blog subscribers. I will send you a link to download it when it is done. Please be patient, as it will take a month or so to edit the articles and put them into the eBook format. If you are not yet subscribed, you can do so using the subscription form at the top-right of your screen

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Subscribe to receive all upcoming articles from

Trentino Genealogy!

Desktop viewers can subscribe using the form

at the right side at the top of your screen.

If you are viewing on a mobile device and cannot see the form,

you can subscribe by sending a blank email to trentinogenealogy@getresponse.net.

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

References

BAILO, Luigi. 2000. Ricordando… Dedicato ai Caduti della Prima Guerra Mondiale dell Giudicarie Esteriore.

NOTE: Ricordando is also out of print, but you can sometimes find it in Italian bookshops. The book is about all the soldiers from Val Giudicarie who perished in World War 1. While a goldmine on some levels, I have found many errors in it. Men frequently had the wrong birth date or the wrong age at time of death listed. In at least one case, the author had listed the grandparents of the man, instead of the parents. I ended up noting all the errors I found and writing to the archdiocese to double check whether the error was in the book or with my own data. In every case it was an error in the book. Unfortunately, the author is now deceased and an updated printing of the book is almost surely never to happen. Still, even with the errors, the anecdotal information he had gathered via postcards and letters he had gathered from the families made it a rich and invaluable resource.

BOLOGNANI, Bonifacio. 1981. A Courageous People from the Dolomites: The Immigrants from Trentino on U.S.A. Trails.

NOTE: This book is out of print and is VERY expensive when you find it used. There are a few sites that offer a downloadable PDF version of the book for free, but you do have to give them your email address. One such site can be found at: https://www.e-bookdownload.net/search/a-courageous-people-from-the-dolomites . I cannot vouch for its quality, as I haven’t downloaded it myself from them.