Genealogist Lynn Serafinn talks about how our ancestors named their children, and gives tips for making sense of names in their often-confusing parish records.

Last time, we took a whirlwind tour around the many idiosyncrasies of the surnames of Trentino. I really just scratched the surface in that article, aiming simply to provide some rules of thumb when researching Trentini family names. Now, as promised at the end of that article, we’re now going to take a look at our ancestors’ FIRST and MIDDLE names. We’ll be looking at how our ancestors’ names changed when they migrated across the ocean, how and why parents chose names for their children, and crucial things to remember when working with old parish records (1500s – 1800s).

SIDENOTE: While I will be referring to my own research (with specific examples from Bleggio in Val Giudicarie), the basic principles I will share here are useful for ANYONE constructing their family history within countries that utilise parish records to record baptisms, marriages and deaths.

Name Changes After Migration

Most of you reading this probably have a family member who changed his/her first name after leaving Trentino for the Americas. If your grandfather was known as ‘Joe’ in America, chances are his birth name was the Italian equivalent, Giuseppe. Antonio would become Anthony or Tony, and Giovanni would become John. In my family, my grandfather was born Luigi, but he changed it to the English equivalent ‘Louis’ about ten years after he migrated (he also changed our surname from Serafini to Serafinn, as I discussed in the previous article).

While many first names were easily translatable into English, some names had no real English equivalent. When that was the case, people often changed their name to something that sounded like their Italian name, rather than a translation of it. That means your Uncle Ned and Auntie Mabel might actually have been Zio Nerino and Zia Amabile.

There are also cases where a person’s name bears hardly any resemblance to the original at all. For example, my father’s first name at birth was ‘Romeo’ – hardly a good name for an immigrant boy in early 20th century USA where ‘men were men’. So, he changed his name to something unquestionably masculine and ‘rugged’ – Ralph. Except for the first letter, it has nothing in common with his original name.

Some people changed their name simply because they didn’t LIKE their birth name. My great-aunt Rustica Fausta Onorati changed her name to ‘Lena’, solely because she hated the name Rustica! Unless you happened to know her birth name was actually Rustica (fortunately, I did), you would never find her in the parish records, as the two names bear no similarity to each other whatsoever.

TIP: I often come across family trees where a person is listed under their ‘adopted’ name rather than their birth name. Personally, I find this very confusing, and I think it can lead a researcher down many dark alleys. I believe it is always best practice to use the name a person was given at birth, and cite any aliases or name changes in your notes about that person. On Ancestry.com, for example, you can write these aliases in a field called ‘also known as’. You can also put them in the ‘person notes’ in software programmes like Family Tree Maker.

Naming Patterns: Keeping Names in the Family

These days, many parents go out of their way to find unusual names for their children. But most of our ancestors were named after elders – parents, grandparents and great-grandparents on both sides of the family.

Generally, naming patterns in Trentino were very regular in the past (especially pre-19th century):

- The first son was typically named after the paternal grandfather

- The first daughter was typically named after the paternal grandmother.

- The second son was was typically named after the maternal grandfather.

- The second daughter was typically named after the maternal grandmother.

Of course, you do find exceptions to the rule. Sometimes a later child will be given the name of one of his/her grandparents, because an elder sibling of the father or mother already had a child of that name.

Naming a Child After a Deceased Parent

Giving Children the Same Name as a Deceased Sibling

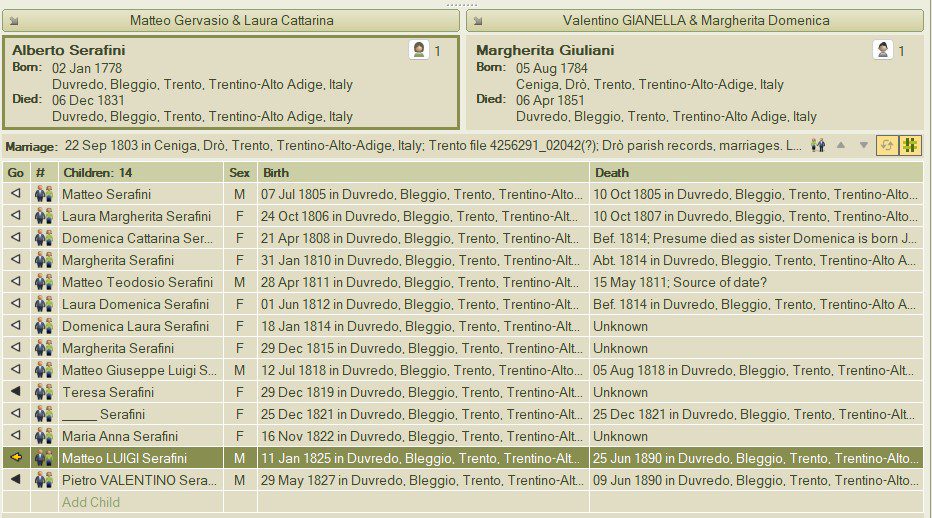

It is EXTEMELY common to see families with two or more children with the same name. Ninety-nine percent of the time (I have found a rare exception), this is an indication that the previous child with that name died in infancy.

For example, my 2x great-grandfather was the fourth Matteo in his family, having had three older brothers, all called Matteo, who died shortly after they were born. In fact, of their 14 children, no more than 6 (and possibly only 3) of them lived long enough to have children of their own.

The reason for this is because Matteo was the name of his paternal grandfather, and his father wanted to make sure he had a son with that name. Ironically, however, Matteo Luigi was known as LUIGI when he grew up!

(Click on image to see it larger)

This brings up another important tip: if you find a birth record with the right name and parents, don’t immediately assume it is your ancestor. Keep looking ahead to locate the births of all children of that family, to see if there is a later child with the same name.

Ordinal Names

Something you might find amusing is that you occasionally see names that indicate which number this child was in the family. For example, boys’ names like Primo, Secondo, Ottavio and Decimo would indicate they were the first, second, eight and tenth born, respectively. While you might find these names less than ‘inspired’, they can be great clues in your research.

Spelling? There’s NO Such Thing!

In the previous article on surnames, I already mentioned that the concept of standardized spelling did not exist in Trentino until relatively recently. While surnames are affected greatly by this, first names are even MORE variable. Here are a few common examples (but the list is almost endless):

- Bartolomeo, Bartholomeo, Bortholamio, Bortolo

- Margarita, Margherita, Margaretha, Malgarita

- Elisabetha, Elisabetta, Isabetta or Helisabeta

- Cattarina, Chatarina, Catherina, Chatalina

See the previous article on surnames for a few general rules of thumb on how spelling can vary.

IMPORTANT: Always remember that variations in spelling do NOT indicate different people. The same woman might appear as ‘Isabetta Rochi’ in her birth record, but as ‘Elisabetha Rocche’ in her marriage record.

Brush Up Your LATIN!

If you work with parish records, you will discover that nearly ALL first and middle names tended to appear in their Latin forms until the 19th century. What’s interesting is that many Latin names actually look like English. You’ll see Joseph (for Giuseppe), Anthony (for Antonio) and Jacob or Jacobi (for Giacomo). Some Latin first names resemble German names, such as Johannes or Johann (for Giovanni) or Joachim (for Gioacchino). You’ll also see some fabulous old names like Hieronymus (for Girolamo) and Aloysius (for Luigi).

When looking at 19th century records, you might start to see the shift from Latin to Italianised spelling. For example, I’ve seen many an ‘Aloisio’ in early 19th century baptismal records who was later listed as ‘Luigi’ on his marriage record. If you’re not aware that this could be the SAME name (and same person), you might miss the record altogether.

Middle Names Are VERY Important

Before the 18th century, middle names were not commonly used, except in the case of noble families (which were more common than you might imagine). Later, especially from the 19th century onwards, giving a child one or more middle names became a more widespread practice. While the shift towards using middle names was probably seen as a practical means of distinguishing one person from another, it’s my belief that it was also a reflection of the shift in worldview spreading throughout Europe from the end of the 18th century, when beliefs about the importance of the individual and personal expressiveness were becoming increasingly popular.

In our modern, English-speaking culture, middle names are often seen as ‘extra’ names. But for the Trentini genealogist, middle names are extremely important when constructing your family tree, because some people come to be known exclusively by one of his/her middle names. For example, everyone in my family knew my great-grandmother as Europa. If you look at her marriage record, she is called Europa. If you look at her children’s birth records, she is called Europa. But if you try to look up Europa Parisi in the birth records, you won’t find her. Why? Because her birth name was Domenica Filomena Europa Parisi. That’s a mouthful!

Sometimes, you might know the name of the parent of a child, but you cannot find the parent’s birth record anywhere. A few weeks ago, I spent four hours looking for a man named Pietro, who was the father of about 10 children. After trawling through every possible baptismal record, I concluded that his birth name was Giovanni Pietro.

I’ve also seen many instances where a child’s baptism was registered in more than one parish, and the first and middle names were recorded in a completely different order in each of them. When such a thing happens, how can you possibly know which one is THE name of the child? The truth is, you can’t. Sometimes the priest will give you a clue by UNDERLINING the name by which the child will be known. But unless he was insightful enough to do this, you’ll find yourself without a clue of how this child came to be known until you dig further down the line to find their descendants. Also, if you are using transcriptions for your research, instead of images of the original parish records, you will never even be aware the priest underlined the preferred name (unless the transcriber was very thorough).

BOTTOM LINE: Using a middle name as one’s primary name is extremely common in Trentino. So, if the father of one of your ancestors is supposedly Luigi, but you cannot find a Luigi in the birth records, try looking for someone with the middle name of Luigi. (Incidentally, the ‘Matteo Luigi Serafini’ in the family tree above, WAS known as ‘Luigi’ throughout life, not Matteo.)

ABBREVIATIONS are Everywhere!

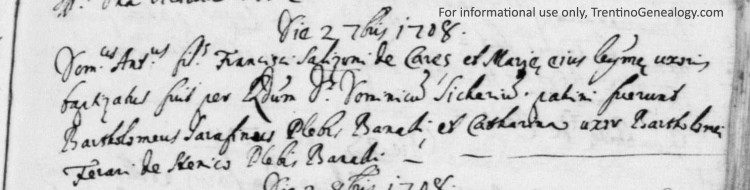

If you work with parish records, you will also encounter many abbreviations of first names. Sometimes these are just shortened versions of the name, such as Bortolo for Bortolomeo, or Gianbatta for Giovanni Battista. But other times, you will see actual abbreviations. You will frequently find Francesco and Domenico written as Fraco and Domco (‘co’ in superscript), and Francesca and Domenica as Fraca and Domca (‘ca’ in superscript). Similarly, Antonio will be abbreviated as Anto (superscript ‘o’) and Antonia as Anta (superscript ‘a’). Needless to say, you have to read very carefully to make sure you’re looking at the record for a male or a female.

One very common (but rather odd-looking) abbreviation is ‘Gua’, which stands for Giovanni. To make things even more confusing, you’ll see Latinized names abbreviated, such as Jo. Bapt for Giovanni Battista, or Domcus (‘cus’ in superscript) for ‘Domenicus’ instead of Domenico.

TIP: The words ‘figlio’ / ‘filius’ (meaning ‘son’) and ‘figlia’ / ‘filia’ (daughter) are almost always abbreviated as figo / figa, fils / fila or simply fo / fa.

Click on the image below to see it larger.

The Link Between Names and WHERE Your Ancestors Lived

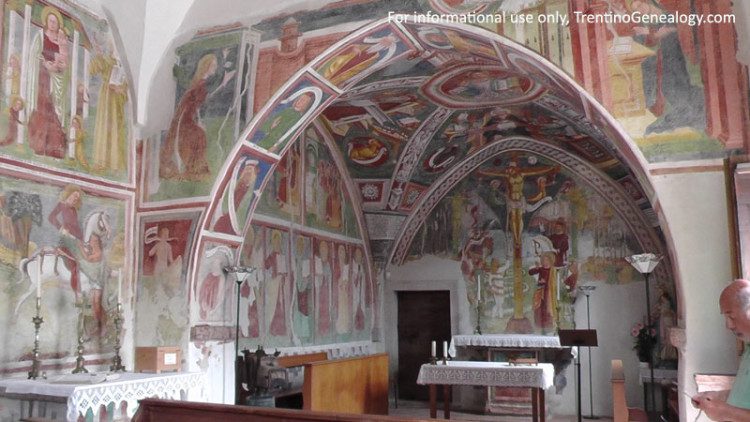

Being familiar with the names of the various frazioni (the tiny hamlets) in which your ancestors lived is also crucial to building your Trentini family tree. In a later article, I’ll talk more about frazioni and how they are tied to our ancestral roots. But for now, as we’re talking about first names, it’s relevant to mention that all parishes – and most frazioni – have their own church, and every church has its own patron saint.

It is not uncommon to see many people in a particular frazione or parish with the same first name because they are named after their local patron. For example, you’ll see a lot of boys named Felice in the frazione of Bono in Bleggio, where their patron is Saint Felice. Giustina is a common girls’ name in the frazione of Balbido (also in Bleggio), where Saint Giustina is the patron. On a parish-wide level, the boys’ name Eleuterio was extremely common in Bleggio during the 1500s, as St. Eleuterio was one of the patron saints of the parish at that time (the parish was not known as Santa Croce until after 1624). In the parish of Saone, I recently discovered a glut of boys named Brutius (Latin for Brizio), as their local patron is Saint Brizio.

Click on the image below to see it larger.

Proximity to Patron Saints’ Feast Days

Aside from village patrons, there are also patron saints for specific days. I came across a record for a Giorgio (George) who was born on April 23rd – the feast day of Saint George. I have seen more than one Giuseppe Maria (Joseph Mary) born during Christmas week. I also found a girl named Epifania born on the day of the Feast of the Epiphany (January 6th) and many baby girls named Pasqua around Easter time (Pasqua means Easter). Being aware of the various patron saints can help you understand why your ancestors may have been given their specific names.

Closing Thoughts

If you really want to find out who you are, it all starts with the names of your ancestors. Far more than simple designations, these names are drenched in meaning, culture and history. If you’re like me, sometimes you’ll find a particular name that draws you in and gets you really curious. Sometimes, you’ll find yourself loving this great-great-great-grandparent because of their wonderful name. These emotions are what give genealogy the power to connect us with our past and transport our ancestors into the present. If you haven’t yet started to trace your Trentini ancestry (and all the other ancestral roots you might have), I encourage you to make a start.

Coming Up Next Time…

Next time, I’ll be giving you tips on finding your FEMALE ancestors from Trentino. Finding your great-great-great-great-grandmother is not always as straight-forward as you might think! Drawing upon my own research for the ‘One Tree’ project, I’ll be sharing some of my very best ‘genealogical detective’ strategies for finding all the wonderful women who contributed to your DNA through the centuries.

I do hope you’ll subscribe to Trentino Genealogy blog (see the form on the top-right side of this page), to receive that and all future articles on this site.

Until then, I look forward to reading your comments or questions about this article below. And if you have any comments OR questions about Trentini genealogy, I cordially invite you to drop me a line via the contact form on this site.

I look forward to connecting.

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

Subscribe to receive all upcoming articles from Trentino Genealogy! Desktop viewers can subscribe using the form at the right side at the top of your screen. If you are viewing on a mobile device and cannot see the form, you can subscribe by sending a blank email to trentinogenealogy@getresponse.net.

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

View My Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

LYNN SERAFINN is a bestselling author and genealogist specialising in the families of Trentino. She is also the author of the regularly featured column ‘Genealogy Corner’ for Filò Magazine: A Journal for Tyrolean Americans.

In addition to her work for clients, her personal research project is to transcribe all the parish records for the parish of Santa Croce del Bleggio (where her father was born) from the 1400s to the current era, as well as to connect as many living people as she can who were either born in Bleggio or whose ancestors came from there. She hopes this tree, which already contains tens of thousands of people, will serve as a visual and spiritual reminder of how we are all fundamentally connected.

View the Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

CLICK HERE to view a searchable database of Trentini SURNAMES.