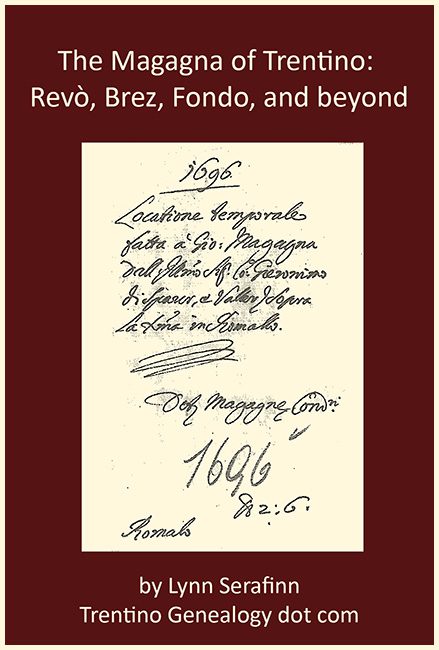

Origins, events, and migration of the many MAGAGNA lines of Trentino, from Revò in the early 1400s, to Brez, Fondo, Castelfondo, Segonzano. By genealogist Lynn Serafinn from Trentino Genealogy.

Want to keep this article to read offline? You can purchase it as a 28-page printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, appendix, maps, footnotes and resource list. (The appendix contains a long list of parchments that contain too much information for the online version).

Price: $3.25 USD.

Available in LETTER size or A4 size.

| Buy LETTER-size PDF: | |

| Buy A4-size PDF: |

OR, CLICK HERE to find this and other genealogy articles in the ‘Digital Shop’.

INTRODUCTION

Origins of the Surname ‘Magagna’

Surnames are beautiful things. They are not just labels of convenience, but linguistic windows into our ancestral past. They aren’t really all that old, in the span of history. In Trentino, for example, we don’t really find them being used amongst ‘commoners’ until after the Black Death (1347-1353). And even then, they were often still very much in a state of flux, which many variant spellings, for the next few centuries.

On the Italian peninsula, including Trentino, there are four primary types of surnames:

- Patronymic – which are derived from the PERSONAL NAME of a patriarch.

- Toponymic – which are derived from the PLACE where the family lived, sometimes their place of origin. This place is always the name of a town, valley, etc. Often, it can refer to a homestead, a town square, or even just a hill or a big rock.

- Occupational – which are derived from the OCCUPATION of a patriarch, and is sometimes the family occupation throughout the generations.

- Supranominal – which are derived from NICKNAMES, either for a specific person, or a ‘soprannome’ used by the whole family. Please note that I am not even sure ‘supranominal’ is an actual word; but if it’s not, I’m ‘inventing’ it here.

There are other surnames that are derived from names of plants, flowers, animals, etc., but these are less common than the four above.

Of the four main types of surnames, patronymic surnames are by far the most common in Trentino, possibly comprising about two-thirds of all its surnames. These are easy to spot, as they often just have a man’s name followed by the letter ‘i’, which is a genitive case ending in Latin, roughly meaning ‘of’ or ‘belonging to’ so-and-so. My own family surname ‘Serafini’ (from the male personal name ‘Serafino’) is one of thousands of examples.

Less common in number are those surnames in Trentino are those in the ‘supranominal’ category. The word ‘soprannome’ literally means ‘above/on top of the name’, i.e., something that is added to a person’s name for a specific reason. Most of you who are familiar with Trentino genealogy will be familiar with this word, when it is used as a ‘nickname’ (although I don’t particularly like this term) for a specific branch of a family, to distinguish it from others who share the same surname. If you are unfamiliar with this term, I recommend that you read an earlier article I wrote called ‘Not Just a Nickname: Understanding Your Family Soprannome’.

Sometimes a family will adopt the soprannome of their family as the primary surname over time. The Tosi of Balbido in Val Giudicarie (who were originally a branch of the Crosina family there) are one of several examples I could give. In the case of the Magagna, one branch of the family actually DID have a soprannome, which was often seen recorded in older documents instead of the surname, but they never actually gave up their surname ‘Magagna’ or permanently replace it with the soprannome. I’ll come back to this subject later in this report.

But sometimes, the ‘nickname’ belonged to a specific person, not necessarily an entire family. It would have been something that other people had called that person, and not a name he (as it’s always a ‘he’ in patrilineal societies) had been given at birth. Sometimes, these nicknames were some sort of physical characteristic of the patriarch or patriarch’s family. The surname ‘Rossi’ (which is actually one of the most commonly found surnames in all of the Italian peninsula, including Trentino) is a perfect example. It comes from the word ‘red’ and would have been used as a nickname for a man or a family who had either a ruddy complexion, or reddish hair. ‘Rizzi’ is another example, referring to a person/family with curly hair.

But other nicknames were given to a person – sometimes in teasing, or possibly even a judgemental way – to describe some personality trait, behaviour, or even a misfortune. This appears to be the case for the Magagna.

In modern Italian, the word ‘magagna’ means a flaw or a problem of some kind. Linguistic historian Aldo Bertoluzza, thus, says the surname Magagna would originally have come from a soprannomi given to someone who had some sort of defect, ailment, or misfortune.[i] Author Enzo Leonardi offers a possible alternative etymology, saying it could have come from the word for a hand-thrown projectile of some kind.[ii] In either case, it is apparently a surname derived from a nickname, and not from a personal name or occupation.

Of course, there is no way to know exactly what this ‘defect, ailment, or misfortune’ could have been, or whether it was physical, personal, or economic. While not a particularly common surname (there are an estimated 612 families with this surname living in Italy today),[iii] it is found not only in Trentino but also in other parts of Italy. It appears mostly in the north, with the highest number appearing in the provinces of Padova and Verona in the region of Veneto. In fact, there are far more Magagna in those places than in Trentino.

So, if the surname is indeed derived from a nickname given to some unfortunate person or family in the past, we have to be open to the possibility (if not the likelihood) that there could have been more than one such unfortunate person who was given this ‘label’. Bertoluzza, for example, cites a document from 1292 where this soprannome appears in Valsugana,[iv] but as surnames were not even in common practice in that era (and given the fact that the Magagna of Trentino had no known historic connection with Valsugana) that particular person may have no connection whatsoever to the Magagna families of later centuries. Nor is it necessarily the case that the Magagna of Trentino came from the Magagna of another province (or vice versa).

As an entity, the Magagna of Trentino date back at least to the first few generations after the Black Death. Who knows? Perhaps the Black Death even had something to do with the ‘misfortune’ that is inferred within the surname itself. For now, we can only speculate about the (possibly) sad beginnings of this family. Whatever misfortune they might have had in the past, they have been tenacious throughout the centuries, still flourishing in the province today.

And Magagna is also one of the most commonly shared surnames among my many genealogy clients.

The Magagna of Trentino: Overview

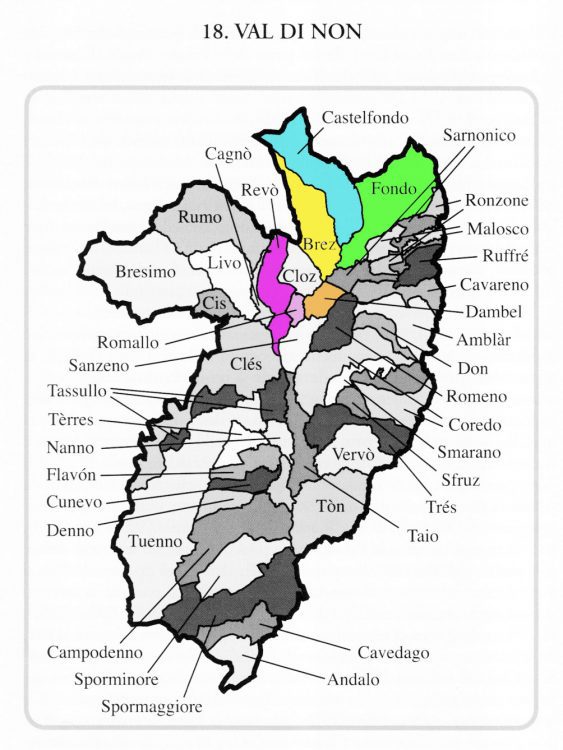

In Trentino, Magagna is historically most closely associated with the parish of Revò in Val di Non (including its frazione of Romallo), with later branches expanding from Revò into Brez and Fondo. All three of these lines continue to this day.

There were also lines in Castelfondo and Dambel, both of which went extinct in the 18th century.

Later, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, we also find two very short-lived ‘twigs’ in Mestriago di Commezzadura in Val di Sole as well as in Segonzano in Val di Cembra (not shown in the map above).

In every case, all these Magagna lines in Trentino can ultimately trace their roots back to the Magagna of Revò. Thus, everyone who has (Trentino) Magagna in their line of ancestors are related to each other. While most will be able to identify a connection within the past 500 years (as most will be within the range of documentation), even the more distantly related would eventually find a connection within the past 600-650 years.

In this article, we will explore the lives of the early families from each of these branches, roughly in chronological order of their appearance, with some historical highlights that I hope will bring them to life.

PART 1: The Magagna of Revò (late 1300s to present day)

The Earliest Recorded Magagna

We know the Magagna were living in Revò at least by the late 1300s.

The earliest document I have found for them is dated 19 July 1472, where a Giovanni Domenico Magagna of Revò, son of the late Giuliano, sells a plot of arable land to the sindaco (mayor) of the parish of Preghena.[v] As Giovanni Domenico would have been a legal adult at that time (i.e., at least 25 years of age), he would have been born no later than 1440 or so, and that his late father Giuliano was perhaps born about 30 years earlier (so, roughly around 1410).

Then, in 1516, we find a ‘Paolo, son of the late Pietro, son of the late Giovanni Magagna of Revò settling a debt owed to Count Antonio Thun. Using the same logic, this places the deceased Giovanni in roughly the same generation as the above-mentioned Giuliano.[vi]

Timewise, then, it is feasible Giuliano and Giovanni were brothers or first cousins, but of course we can only theorise this, given the scarcity of documentation in this era. In any case, knowing that people back then were very particular about recording one’s native village in documents, and we find no mention of the Magagna having been from anyplace other than Revò, we can safely presume that their father(s) was/were born in Revò the late 1300s. But without more data, I wouldn’t venture to guess how many Magagna family groups were living in Revò at that time, nor whether the surname was indigenous to Revò.

The Decima of Cloz

For a time during the 1500s, the Magagna of Revò owned the rights to the decima of Cloz. A decima was a mandatory tax to be paid annually to the local Counts, who, in this case, were the noble Thun family. The word decima means ‘one tenth’; hence the tax was usually 10% of one’s annual assets unless a household was destitute or otherwise exempt. This decima was typically paid in goods, such as grains, livestock, etc., rather than money.

As the territory over which the Counts had dominion were often quite vast, they frequently appointed agents to do the ‘legwork’ of collecting the decima on their behalf in each comune (municipality). In exchange for his work, an agent would be entitled to a share in the takings. Thus, obtaining the rights to collect the decima of a thriving comune could be quite lucrative for the agent, and the rights themselves were also a tradeable commodity.

In awarding someone the rights to a decima, the Count would have to have considered the person to be trustworthy, as well as someone with whom he could work well at a personal and professional level. We already know from the 1516 document that the Magagna were at least acquainted with the Lords of Thun.

While I haven’t found any reference for when the Magagna were granted this decima, we do know they relinquished it on 14 February 1574, when Giacomo, son of the late Giovanni Magagna of Revò, ceded his rights to a Sigismondo Torresani of Romeno, for the purpose of paying off a debit owed to him.[vii] Although I cannot be certain, in terms of timing (and the fact that we know the family apparently had some sort of professional relationship with the Thun), I would theorise that this Giovanni might have been a grandson of the one whose name appeared in the 1516 document.

Deputy of Health During the Plague of 1575

Moving ahead to 1576, we meet a ‘ser’ Bartolomeo Magagna of Revò (whom I estimate was born in the 1540s), who was one of three men who had been assigned as deputies of health for Val di Rumo during the plague epidemic of 1575.[viii] The document shows the residents of Rumo reaching an agreement with them on a fair payment for their services.

Just a few years later, we find this same Bartolomeo transferring from Revò to Brez; we’ll look at his story in detail later in this article.

Two Separate Lines

By the time of the 1624 Revò census,[ix] we find a total of eight Magagna households living in Revò (albeit two of them are older couples). However, half of these households were not entered under the surname ‘Magagna’, but under the family soprannome ‘MINA’ (frequently written ‘della Mina’, ‘del Min’ or ‘del Mino’). Although ‘Mina’ and its variants ceases to be used as a replacement for the surname by the 1700s, I have found it used as a soprannome alongside the surname in records as late as 1798.

For lack of a better system, I will refer to the line who used this soprannome as the ‘Mina’ line, and to the line who used the surname ‘Magagna’ with no soprannome (at least none that I have found) as the ‘main’ Magagna line. This is not to infer that the ‘main’ line was better or bigger; indeed it is the Mina line that continues to the present day.

The very fact that this soprannome existed in 1624 is very informative. The high number of family groups, plus the fact that a soprannome was needed to differentiate the various lines, both reinforce what we already know about the Magagna – that the surname had already been present in the parish of Revò for many generations by the early 1600s.

I believe we can speculate as to the origin of the soprannome. ‘Mino’ is a diminutive form of several different male personal names, including ‘Giacomino’, a common nickname for GIACOMO. I am fairly certain the ‘Mina’ line was descended from a Giacomo, but he would have been an earlier Giacomo from the one who relinquished the decima in Cloz in 1574. Perhaps he was his grandfather, or even an earlier generation. My reasoning is twofold. First, the Giacomo in the 1574 document had a contemporary named Giovanni, whose descendants also used this soprannome, so therefore this Giacomo cannot be the patriarch from whom the soprannome was derived. Also, there were at least eight males named Giacomo born in these Mina lines between the mid-1500s and the mid-1600s. To me, all of this points to the existence of an earlier Giacomo, who would have been born in the mid-1400s or earlier.

The separation between the ‘Mina’ line and the ‘main’ Magagna is made even more distinct by their choice of personal names into the early 1600s. For the ‘Mina’, the most frequently recurring male personal names are Giacomo, Tommaso, and Stefano, whereas in the ‘main’ line, their most frequently recurring male names are Giuliano (or Giulio), Federico, and Giovanni. In the ‘main’ line, for example, there were at least two Magagna priests named Giuliano or Giulio in the 1600s. The elder was a Jesuit priest born about 1590,[x] and the younger was his grand-nephew Giulio Floriano Magagna born in 1654.[xi] We find the name Federico (frequently ‘Giovanni Federico’) recurring in the main line well into the 19th century.

While the ‘Mina’ and the ‘main’ Magagna lines were surely descended from the same ancient ancestor in the 1300s, once they identified themselves as two different lines, their respective trajectories became quite different.

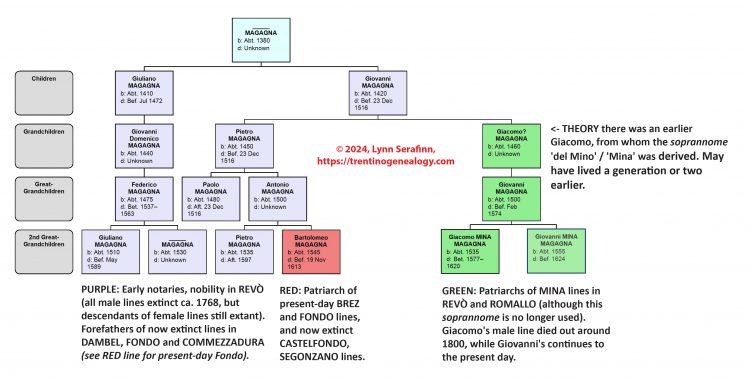

THEORY: Overview of Early Magagna

Before moving forward in time, I would like to offer this hypothetical construct of the early Magagna in Revò, and how they ‘feed’ into the later generations to come.[xii]

CAVEAT: This chart is HIGHLY speculative, very general, and probably contains many inaccuracies. Thus, I urge you to look at it only as a rough guide to how the two lines progressed from the 1500s forward, rather than a definitive ancestral chart of earlier generations. And, of course, it contains only the names of the men, partially because they are the ones who carry the surname, and partially because women’s names are largely absent in early documents.

I have tried as much as possible to construct this chart using references in legal parchments. When I did not know the name of a man’s father, I placed him in what I felt was the most likely position, based mostly on naming patterns of his children. For example, I really have no idea who Bartolomeo’s father was, but I presume he was a descendant of Pietro, partially because the names Pietro, Giovanni, and Antonio appear in the names of his children, and also because he is never referred to as ‘Mina’ in any record.

As already discussed, I presume there was a ‘Giacomo’ no later than the mid-1400s, who was the patriarch of the ‘Mina’ line. However, he could have been born a generation (or two) earlier than where he is in this chart, which would push the date of separation of the two lines back further in time. It is even possible they were already ‘split’ by the end of the 1300s. Also, I am not sure that the Giovanni born circa 1555 was the brother of Giacomo (he was definitely not his son); he may have been a cousin. Either way, they both would have been descendants of the original ‘Giacomo’ (or Giacomino) from whom the soprannome was derived.

Using Family Tree Maker software, I colour-coded the descendants of all of these early patriarchs (more colours than what is shown in the above chart), which enabled me to identify which lines are still in existence, and which have gone extinct. Please remember that when I say ‘extinct’, I am only referring to the male lines, as those are the lines that would carry the surname. I know for sure that some of these ‘extinct’ lines still have living descendants (some of my clients are among them) under other surnames, via their female descendants.

Despite its probable errors, if we use this chart as a very ‘liberal’ point of reference, it can help us get a clearer picture of the evolution and expansion of the Magagna family throughout the centuries, not just in the parish of Revò, but also in the various places to which they migrated in coming generations.

The Magagna Notaries of Revò

From the mid-1500s through the latter half of the 1600s, we find no fewer than six Magagna notaries – all from Revò. Five of these six were from the ‘main’ Magagna line. These were:

- GIULIANO – Son of Federico; born around 1510. Active in his profession at least between 1537–1563.[xiii], [xiv] He appears in the ‘purple’ line in the chart in the previous section.

- PIETRO – Possibly a 1st cousin of Giuliano, born around 1535. Active in his profession at least between 1561–1597.[xv], [xvi] Again, he is in the ‘purple’ line in the chart in the previous section.

- FEDERICO – son of the above-mentioned Giuliano; born around 1560. I have found him in only one document from 1613.[xvii] He is alive at the time of the 1620 tax census, when there are said to be 6 people living in his household.[xviii] In the 1624 census for Revò, he is cited as deceased, and called ‘egregio’, which is an honourific used with notaries.[xix]

- GIROLAMO – grandson of the above-mentioned Federico, born 8 Feb 1630.[xx] An important person in the timeline, I will discuss him in more detail in the next section.

- FRANCESCO CRISTOFORO – son of the above-mentioned Girolamo, born 25 July 1667.[xxi] Although I have not found any pergamene with his signature, he was surely practicing his profession by 1693, as we find him called ‘spectabilis’ in many parish records, including the baptismal records of his children,[xxii] and his death record (8 September 1712).[xxiii]

The only notary I have found from the ‘Mina’ line was MICHELE, born 8 December 1627 (son of Giacomo and Clara),[xxiv] who is cited as a notary in the baptismal records of several of his children between 1653-1675, and is also called ‘spectabilis’ in his death record (1 July 1676),[xxv] which is another honourific used only for notaries. I have not found any pergamene drafted by him on the Archivi Storici del Trentino database.

The Noble Girolamo, notary, and Descendants

Born in Revò on 8 February 1630,[xxvi] Girolamo Magagna came from the ‘main’ Magagna line. Following in the footsteps of his grandfather (Federico) and great-grandfather (Giuliano), he worked as a notary from at least 1655–1679.[xxvii] By all accounts, Girolamo appears to have been one of the most active Nonesi notaries of his generation. What is most noticeable when you read through his documents, is that nearly all of the pergamene he drafted are land purchases made by Count Cristoforo Riccardo Thun, son of the late Ercole Thun.

In the baptismal record of his eldest son Pietro in 1652, Girolamo is referred to as ‘DD’, i.e. ‘Doctor Divinitatis’ or ‘Doctor of Divinity’.[xxviii] While in some countries this was a high-ranking academic degree, during this era it could also have been an honorary degree awarded by the bishop.[xxix] In Trentino, the bishop was actually the Prince-Bishop of Trento, who was then Carlo Emanuele Madruzzo (reigned 1629-1658). It is possible this was the case, as I haven’t found him among the graduates of either the University of Bologna or Padova, whereas his elder brother Federico received his degree in Padova in 1650.[xxx] In any case, Girolamo was surely very young to receive such a title.

Girolamo and his wife Maria[xxxi] had at least 10 children together between the years 1652-1675. While he is frequently referred to as spectabilis (signifying he was a notary), the first time we see the word ‘noble’ is in the baptismal record of their last child, a son named Felice, born 31 May 1675.[xxxii] Girolamo is also called ‘noble spectabilis’ in his death record on 2 August 1682.[xxxiii]

From this date onward, we see the word ‘noble’ appearing in many records for their descendants. Their son Giulio Floriano,[xxxiv] a Catholic priest, is called ‘noble’ in his death record on 12 November 1686.[xxxv] Later (1695-1705), nobility is mentioned in the baptismal records for at least three of the children of their son, the notary Francesco Cristoforo.[xxxvi]

Enigmatically, I cannot find any information about the stemma or the diploma of nobility for this Magagna family. I would expect to find them listed in my (many) sources on nobility if their title had been imperial (i.e. awarded by the Emperor).[xxxvii] If, on the other hand, their title was episcopal rather than imperial, it would have been granted by Prince-Bishop Giovanni Michele Spaur (reigned 1696-1725). It that was the case, there may be some record of it in the Archivio di Stato in Trento (something for my ‘to do list’ in the future). Sadly, this line died out very quickly, with the death of Francesco Cristoforo in 1712.[xxxviii] Perhaps the brevity of this noble family explains why they seem to be missing in the history books. Had they lived on, future generations would have surely obtained confirmation/renewal of the title at some point, and we would know more about the original award.

The Decima of in Romallo

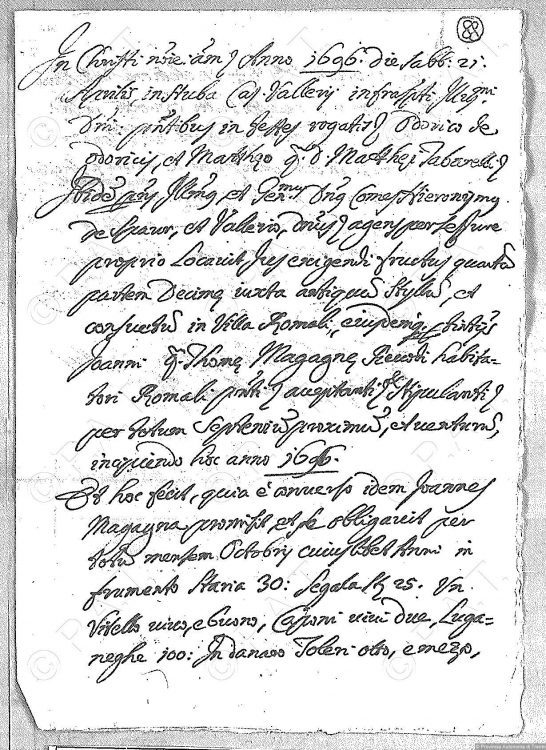

By the end of the 1600s, we find various branches of the Magagna living in the village of Romallo, which historically was part of the parish of Revò for many centuries. We see, for example, Giovanni, son of Tommaso ‘del Min’ Magagna, shifted from Revò to Romallo after he married Margherita Pancheri of that village in 1679, [xxxix] where the couple had at least eight children.

The move was apparently a lucrative one for Giovanni as, in 1696, Count Girolamo Spaur leased him the rights to one-quarter of the decima collected in Romallo for a period of seven years. In exchange, Giovanni would pay the Count an agreed amount of wheat, rye, and farm animals.[xl] On the Archivi Storici del Trento website, we find this digital image of a photocopy of the original document. About halfway down, you can see the Latin words ‘Joanni q(uondam) Thomas Magagna Revodii habitatori Romalli’ (Giovanni, son of the late Tommaso Magagna of Revò, living in Romallo.

Although this was the first Magagna family to have lived in Romallo, their descendants apparently shifted back to Revò in the mid-18th century. However, a later Magagna family, again from the Mina line, again moved from Revò to Romallo a century later, when a Filippo Giovanni Battista Magagna married another Pancheri woman of Romallo in 1833.[xli] From what I can tell, these are the ancestors of the Magagna who were living in Romallo in the first half of the 20th century (and possibly to the current day). Of course, other Magagna family groups may have moved there since that time.

PART 2: Magagna of Brez (1579 – present day)

Revò –> Brez

Earlier I mentioned a ‘ser’ Bartolomeo Magagna of Revò (from the ‘main’ Magagna line), who had been one of the deputies of health during the plague of 1575. In 1579, just three years after he received payment for his services as health deputy, we find this same Bartolomeo acquiring the rights to manage a mill in Brez. Located on the Novella river, this mill was called ‘Molino de Bon’, apparently named after its previous manager, Bono Clauser of Romallo.[xlii]

IMAGE: Present-day view of the Molini de Bon (Mills of Bon) on the Novella river in Brez[xliii]

After acquiring the rights to the mill, Bartolomeo moved to Brez to take up his new profession. Sometime before 1582, he married a woman named Libera. I have found baptismal records for six children born to Bartolomeo and Libera between 1582-1595, and there were also two elder sons (as per references in various parchments) whose births pre-date the beginning of the parish register.[xliv]

Altogether, Bartolomeo had 5 sons (I cannot be certain that Libera was the mother of the two elder sons, or if they were the sons of an earlier wife). His son Giovanni became a priest, but the other four all married and had their own families, fathering at least 24 children among them.

A Dynasty of Millers – the Descendants of Bartolomeo

These four sons – Pietro, Giorgio, Stefano, and Giovanni Antonio – all continued their father’s profession as millers. This profession was nearly as enduring as their surname, as I have found nearly 30 Magagna men who worked as millers from the late 1500s to the late 1800s, and there were probably others I haven’t yet identified.

‘Double’ Magagna – Two Pedigree Collapses

While all of the existing Magagna lines of Brez are ultimately descended from the four sons of Bartolomeo and Libera, some Magagna in Brez inherited the surname via Magagna men who married one of their female descendants.

For example, we find a ‘double’ Magagna line n Brez, which started when Giovanni ‘Tommaso’ Magagna of the ‘Mina’ branch of Romallo marries Anna Maria Magagna of Brez on 28 November 1710.[xlv] The couple were 4th cousins, a relationship that did not require a church dispensation. Technically, this started a NEW branch of Magagna in Brez, as the surname was inherited via a line not descended from Bartolomeo. This means (if my configuration of the early Magagna is correct) that descendants of this couple have Magagna ancestors from BOTH the ‘main’ Magagna line and the ‘Mina’ line.

We find another ‘double Magagna’ marriage in the very next generation, when Giovanni Magagna of Brez (son of the above couple)[xlvi] married Maria Anna Magagna of Brez[xlvii] on 17 November 1739.[xlviii] Again, this couple were 4th cousins.

I have traced these lines into the early 20th century, and many of the present-day Magagna appear to be descended from one or both of these pedigree collapses.

Ruffini tells us that more than 30 Magagna emigrated from Brez between the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[xlix]

PART 3: Magagna of Castelfondo (1629-1783)

Revò –> Brez –> Castelfondo

In 1619, Giovanni Antonio Magagna of Brez – the youngest son of Bartolomeo Magagna of Brez and his wife Libera – married Flora Genetti of nearby Castelfondo.[l] In their marriage record, we learn that Flora’s father, Giovanni Genetti, was also a miller. I believe this professional connection between the two families may have played a role in the establishment of a new Magagna line that sprang up in Castelfondo in their children’s generation.

The short-lived Castelfondo line was started by two sons of Giovanni Antonio Magagna and Flora Genetti: Bartolomeo and Stefano.

Born in Brez on 14 February 1629, Bartolomeo was the elder of the brothers.[li] At the age of 20, he married a Margherita Piechenstein of Castelfondo,[lii] after which the couple settled in Margherita’s home parish rather than in Brez. In the baptismal record of their first child, Flora, in 1651, we learn that the young Bartolomeo was a miller – but in Castelfondo rather than in Brez.[liii] While this is just my personal speculation, as we know from various references that Bartolomeo’s maternal grandfather, Giovanni Genetti, was already deceased by this time,[liv] it seems feasible that the rights to the use of the mill in Castelfondo may have been passed on to the (Magagna) sons of Flora Genetti. I would be interested to know if there is any documentation to that effect.

Although Bartolomeo and Margherita had several children in Castelfondo, their only surviving son, Giovanni Battista (who worked as a miller after his father’s death in 1671),[lv] did grow up to marry, but he died at the relatively young age of 41,[lvi] apparently leaving no children.[lvii]

At this point, the Magagna would have died out in Castelfondo had it not been for Bartolomeo’s brother Stefano. It was Stefano whose descendants would continue in Castelfondo until the second half of the next century. Their struggle for survival, however, appears to have been a difficult one.

Stefano was a challenging person to identify, for a variety of reasons. First, there does not seem to be a baptismal record for him. Nor have I been able to find a marriage record for him and his wife, Anna Maria. Also, in one of his children’s baptismal records, he is said to have come from Revò, not Brez. However, in a baptismal record dated 24 April 1662, we find a ‘Stefano of Brez, called Magagna,’ cited as the godfather of the above-mentioned Giovanni Battista Magagna (son of Bartolomeo and Margherita).[lviii] This, along with the fact that Stefano’s first daughter was called Flora (named after his mother, Flora Genetti), surely confirms that he was the (younger) brother of Bartolomeo. His death record in 1672 says he was ‘about 35’,[lix] which would put his birth date around 1637, but I believe he may have been born around 1633, where there is a 4-year gap between the births of his siblings. The early 1630s are often patchy in parish registers, as there was a major outbreak of plague in the province in 1630.

Living in Castelfondo, Stefano and his wife Anna Maria had six children, only one of whom was a son, namely Giacomo Antonio, born in Castelfondo on 17 Jun 1667.[lx] Although I have found no mention of Stefano’s occupation, Giacomo Antonio Magagna cited as being a miller in several documents, including his marriage and death records. Like his father, Giacomo Antonio died at a very young age – just one day before his 34th birthday.[lxi]

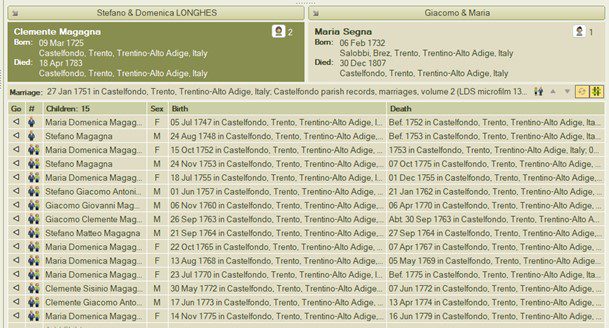

Despite the brevity of his lifespan, Giacomo Antonio Magagna and his wife Margherita Turra[lxii] had one child – a son named Stefano, named after Giacomo Antonio’s father. This younger Stefano, who continued to work at the mill in Castelfondo, had many children with his wife Domenica ‘Longhes’ Genetti of Dovena (a frazione of Castelfondo),[lxiii] but apparently only their eldest son, Clemente Magagna,[lxiv] reached adulthood and had children. Again, like his forefathers, Clemente worked as a miller.

But here is where the story becomes so tragic, it is almost impossible to imagine.

Clemente was married twice: first to (another) Margherita Turra of Castelfondo, and then to Maria Segna of Salobbi (parish of Brez). Not quite 20 years old when she married Clemente,[lxv] Margherita born him two children – a son and a daughter – both of whom died in infancy.[lxvi] Then, about a year after the birth of their second child, Margherita herself died at age 23. [lxvii]

A bit more than a year later, Clemente remarried the not quite 18-year-old Maria Segna of Salobbi.[lxviii] Maria bore him an astonishing 13 children over a 23-year span (1752-1775). But just as astonishingly – and heartbreakingly – every single one of their children died in infancy or childhood, with the exception of their son Stefano, who managed to make it to age 21 before he also died, unmarried, and leaving no children behind.[lxix]

Clemente himself died at age 58, leaving behind a widow who would go on to live another 24 years without him, ultimately passing away at the age of 75, with no children or grandchildren to comfort her, despite all her endurance, suffering, and loss.[lxx] Frankly, I cannot begin to fathom how Maria Segna must have felt, or how she even managed to live to the age she did. She must have been a remarkably strong woman.

And thus, the Magagna of Castelfondo went extinct. I have seen many a line ‘die out’ in my research over the years, but this is one of the most intensely painful extinction I’ve seen that hasn’t been linked to an epidemic. Frustratingly, the priests were not in the habit of recording cause of death in this era (except in the case of accidents), which means we can only guess at what could possibly have caused fifteen children in the same household to die one after the other.

PART 4: Magagna of Fondo (1625 – 1746; 1722 – present day)

Revò –> Fondo

Revò –> Brez –> Fondo

By the early 1600s, the Magagna surname starts to appear in the parish of Fondo. There were at least two separate lines that settled there, both with their roots in Revò.

The patriarch of the earlier line was Gervasio Magagna of Revò, who was already living in Fondo before the Revò census of 1624. From the ‘main’ (non-Mina) Magagna line of Revò, it is my theory that he may have been the son of Giovanni Magagna (born ca. 1569) and his wife Cattarina (born ca. 1574), who are both in their 50s with no children living at home with them at the time of the Revò census in 1624.[lxxi] My further theory is that this Giovanni many have been the son of the afore-mentioned notary Giuliano Magagna (born ca. 1510).

Gervasio’s line of male descendants seems to have died out by 1746,[lxxii] but by that time, another Magagna line had already sprung up in Fondo. This time, they came not directly from Revò but via Brez, when an Adamo Sigismondo Magagna of Brez married Domenica Bertagnolli of Fondo on 11 August 1722.[lxxiii]

Born in Brez on 21 December 1695, Adamo was the son of Giacomo Magagna of Brez and his second wife Domenica Canestrini of Cloz.[lxxiv] Like his predecessors, Giacomo worked as a miller. Adamo Sigismondo was to be his father’s last child, as Giacomo died in 1697, at the age of 41.[lxxv]

Identifying Adamo was a challenge. We find him in Fondo, but his father’s name is not mentioned in his marriage record, nor in his death record. Nor does his father’s name appear in any of his children’s baptismal records, or in any of the eight instances where he is cited as a godfather. Moreover, not one of Fondo records says he came from Brez.

However, there isn’t a single Adamo of any surname born in Fondo between 1670-1705, and the ONLY Adamo Magagna born anywhere within the correct timeframe is Adamo Sigismondo of Brez. Also, the naming pattern of his children is consistent with his parents’ names. As his father would have been deceased since he was an infant, it is certainly feasible his decision to shift locations was influenced by a need to find financial stability, possibly through his wife’s family. I thought perhaps Adamo’s widowed mother (Cattarina Canestrini of Cloz) might have remarried, but I have looked up to 1710 in Brez, Fondo and Cloz, but found no second marriage for her. I have also looked up to 1740 for a death record for her in Brez and 1720 in Fondo, but this search was also unsuccessful.

Adamo died at the relatively young age of 47,[lxxvi] but not before he fathered at least nine children with his wife Domenica Bertagnolli. I have entered all of the Magagna births in Fondo through 1923, and (with the exception of a Magagna or two who were just ‘passing through’ Fondo) all of them are descended from this couple. Barring any families who might have moved there later in the 20th century, I presume all the Magagna in present-day Fondo are also descended from the same couple.

PART 5: Magagna of Dambel (1628 – 1731)

Revò –> Dambel

While the Dambel baptismal registers date back to 1621, the marriage records there do not start until 1641, and the deaths not until 1664. Thus, when researching early 17th century families in Dambel, we have no choice but to do a bit of interpretation based on what evidence we do have.

A short-lived line in Dambel line was founded by a Giuliano Magagna of Revò, who came from the ‘main’ Magagna line. My theory is that he was the brother of Gervasio (whom we discussed in the previous section on Fondo), and he was thus the grandson of the notary Giuliano Magagna (born ca. 1510). We can estimate this Giuliano was born sometime around 1598, give or take a few years.

We know that Giuliano was from Revò via a reference in the baptismal record of his youngest child, his son Andrea, born 11 April 1652.[lxxvii] Although the first child we have for him was his daughter Cattarina on 24 January 1628,[lxxviii] we can Giuliano was possibly already living in Dambel before 1620, and definitely before 1624, as his name does not appear in the 1624 census for Revò, and the tax register of 1620 says there were only three people living in the household of the Giovanni and Cattarina, whom I believe may have been his parents.

Apparently, Giuliano married three times. His first wife, Maria Giacoma, was the mother of the above-mentioned daughter Cattarina. Sometime between September 1631 and early 1633,[lxxix] Maria Giacoma died, as we find the widowed Giuliano remarrying Margherita Gentilini of Romallo on 4 May 1633.[lxxx] Although there do not appear to be any children from this marriage, I did find Margherita listed as a godmother a few months after she and Guliano married.[lxxxi]

We can presume Margherita died sometime before mid-1635, as we begin to find baptismal records for Giuliano’s children with his third wife, Libra, in May 1636.[lxxxii] As mentioned, there are no surviving marriage records for Dambel before 1641, and I have found no marriage record for them in Revò.

Giuliano’s death record is not in the Dambel register. However, as he is said to be deceased when his wife Libra dies on 20 August 1669 (and in references in later records), we know he would have died sometime between the birth of his last child in April 1652 and November 1664, which is when the death records for Dambel begin.

The Dambel line continues for a few generations via Giuliano and Libra’s sons Lorenzo (1636) and Giorgio (1642),[lxxxiii] but the male line dies out before the middle of the 18th century. The last Magagna birth I have found in Dambel is for Giuliano’s great-granddaughter Maria Magagna, born 26 Aug 1719, daughter of Romedio Magagna and Anna Cattarina Pellegrini.[lxxxiv] The last recorded death for a male Magagna in Dambel is for the above-mentioned Romedio, who died 13 March 1731, at the age of 57.[lxxxv]

PART 6: Magagna of Mestriago di Commezzadura (1772 – 1866)

Revò –> Mestriago di Commezzadura

In the late 18th century, Another short-lived Magagna line started in the frazione of Mestriago in the comune of Commezzadura in Val di Sole. The patriarch of this line was Giovanni Battista Magagna, who was born in Revò on 5 September 1747, son of Giovanni Federico Magagna (of the ‘main’ Magagna line) and Orsola Negherbon of Cagnò.

Giovanni Battista married Cattarina Claser of Commezzadura in 1772, settling in Mestriago in his wife’s parish. The couple had had eleven children, although several died in infancy.[lxxxvi]

Of their sons, we know that Giovanni Federico (1781-1854) and Giovanni Giacomo (1789-1828) grew up to have families of their own.[lxxxvii]

Stefano Simone Magagna (born 16 Jun 1822), son of Giovanni Federico and his wife Maria Ramponi, grew up to become a Catholic priest. He passed away at the age of 43.[lxxxviii] [lxxxix]

In 1811, Giovanni Federico ‘and his brothers’ built a house called ‘Casa Magagna’ in Mestriago in 1811. The date of construction is shown on the keystone of the granite jamb of the right door on the ground floor. By 1859, the house was registered in the name of ‘the Magagna brothers (or siblings) and their heirs’.[xc]

The male line died out in Mestriago before the end of the 19th century, as by 1901, the house was the property of Rosalia Maria Cazzuffi (1862-1950), daughter Giovanni Federico’s daughter Rosa Magagna (1826-1867) and her husband Dionisio Cazzuffi of Cogolo.[xci]

In 2003, the house was acquired by the local cooperative society, who then restructured it entirely, splitting it into several apartments.[xcii]

PART 7: Magagna of Segonzano (1818-1836)

Revò –> Fondo –> Segonzano

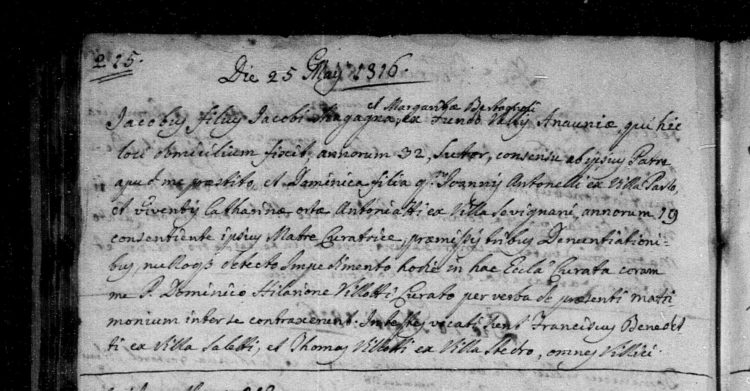

The most short-lived ‘twig’ of the Magagna I have found was in the parish of Segonzano at the beginning of the 19th century. This line started when a tailor named Giacomo Antonio Magagna of Fondo (born 18 November 1782) moved to the parish of Segonzano sometime before 1816. There, he married Domenica Antonelli of the frazione of Parlo in that parish.[xciii]

MY PARTIAL TRANSLATION: 25 May 1816. Giacomo, son of Giacomo Magagna and Margherita Bertagnolli of Fondo in Val di Non, now living here (in Segonzano), age 32 years, tailor, married Domenica, daughter of the late Giovanni Antonelli of the village of Parlo and the living Cattarina Antoniazzi of the village of Sevignano.

The couple had eight children together, three of whom were sons, but as there is no sign of their sons carrying on the surname in later records, I presume they all died young or moved away. Thus, this family never really established itself as a new Magagna line.

CONCLUSION

In my own experience with genealogical research, whenever families migrate from one place to another, the underlying impetus always boils down to one of these two factors:

Misfortune or Opportunity

Or, in some cases, it could be both.

Misfortune – such as wars, plagues, political oppression, and widespread economic hardship – will always trigger migration. Most of our Trentino ancestors who emigrated to the Americas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries left their homeland for one or more of these reasons. Even in our modern world, we see examples of such misfortunes causing mass exoduses around the globe, pretty much on a daily basis.

Opportunity – such as available land, new job openings, or profitable marriage offers – can sometimes come when ‘progress’ opens up new doors of possibility, but they will also (frequently) come as a result of someone else’s misfortune. If a plague or a war wipes out a high percentage of the population in one village, for example, it will cause a ‘vacuum’ where unclaimed lands, unmanned jobs and services, or a lack of available marriage partners puts the survival of that village in a precarious position. The only way to fill those voids and restore social balance is for industrious (and hopefully skilled) ‘outsiders’ to move there from other places.

As we look specifically at the Magagna of Trentino, an interesting irony comes to mind. On the one hand, their very name ‘Magagna’ indicates there had been some kind of ancient misfortune – the kind of misfortune severe enough for the family or patriarch to have been labelled as ‘unfortunate, flawed, or lacking’. But the irony is, that these very same Magagna were actually really good at finding opportunity, sometimes via migration:

- We find them as landowners as far back as the early 1500s.

- While (with one exception) they were not nobility, we find them as the partial owners of at least two decima – one in Cloz, and the other in Romallo.

- In the early 1600s, at least two of them had doctorates.

- We find a fair number of them as notaries in the 16th and 17th centuries, often wheeling and dealing with the Counts of Thun. Indeed, I have found numerous references to various members of the Thun family standing as godparents for Magagna children.

- They were also dedicated (and seemingly successful) business owners, as evidenced by their centuries-long enterprise in the milling industry in Brez and Castelfondo.

In fact, it is only in the post-Napoleonic era at the beginning of 19th century that I found some of the Magagna specifically referred to as contadini (subsistence farmers) in the Revò parish records.

So, if the surname ‘Magagna’ indeed started with misfortune, those who chose to keep this as their surname certainly rose high above whatever those misfortunes might have been. And, while some lines have gone extinct, the overall bloodline is very strong, with descendants still living in various parts of Trentino, and in many other countries.

As mentioned earlier, despite being a relatively uncommon surname, Magagna is actually one of the most commonly shared surnames among my genealogy clients, appearing in nearly 40% of my clients’ family trees. And all of these clients – and indeed all who have Magagna ancestors – are ultimately cousins, mutually connected to that ancient, ‘unfortunate’ patriarch in Revò.

I hope you found this article to be both interesting and informative. if you would like to KEEP it to read offline, you can purchase it as a 28-page printable PDF (27 pages in A4 size) complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, appendix, maps, footnotes and resource list. (The appendix contains a long list of parchments that contain too much information for the online version).

Price: $3.25 USD.

Available in LETTER size or A4 size.

| Buy LETTER-size PDF: | |

| Buy A4-size PDF: |

OR, CLICK HERE to find this and other genealogy articles in the ‘Digital Shop’.

If you have any comments or questions, or if you are seeking help researching your Trentino family, please feel free to contact me at https://trentinogenealogy.com/contact.

Until next time!

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

8 April 2024

P.S. I am currently taking client bookings for June 2024 and beyond. If you would like to book a time to discuss having me do research for you, I invite you to read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, we can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry

(please note that the online version is VERY out of date, as I have been working on it offline for the past 6 years):

https://trentinogenealogy.com/my-tree/

NOTES

[i] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino. Trento: Società Iniziative Editoriali (S.R.L.), page 205.

[ii] LEONARDI, Enzo. 1985. Anaunia: Storia della Valle di Non. Trento: TEMI Editrice, page 392.

[iii] COGNOMIX. ‘Diffusione del cognome Magagna’. From ‘Mappa dei Cognomi’. https://www.cognomix.it/mappe-dei-cognomi-italiani/MAGAGNA. Accessed 13 March 2024.

[iv] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino. Trento: Società Iniziative Editoriali (S.R.L.), page 205.

[v] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Compravendita’. 19 July 1472, Preghena. Giovanni Domenico, son of the late Giuliano Magagna of Revò sells a plot of arable land near Preghena to the sindaco of the church of Ss. Antonio e Leonardo in Preghena. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1015010. Accessed 12 March 2024.

[vi] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Costituzione di censo ed estinzione di debito’. 23 December 1516, Rocca di Samoclevo. Paolo, son of the late Pietro, son of the late Giovanni Magagna of Revò settling a debt owed to Count Antonio Thun. Notary: Baldassare, son of ‘ser’ Sigismondo Visintainer of Terzolas, living in Malé. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/49622. Accessed 6 December 2023.

[vii] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Cessione di diritti’. 14 February 1574, Revò. Giacomo, son of the late Giovanni Magagna of Revò, cedes his rights of the decima in Cloz to Sigismondo Torresani (son of the late Tommaso) of Romeno, for the purpose of paying off a debit. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/3567594. Accessed 12 March 2024.

[viii] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Transazione’. 14 May 1576, Cagnò. ‘Ser’ Bartolomeo Magagna of Revò, along with two others, reach an agreement (after a dispute) for the amount of payment they should receive for work they did as deputies of health during the time of the plague in Val di Rumo. Note: there was a major plague in Trentino in 1575. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1008555. Accessed 12 March 2024.

[ix] Revò parish archives, anagraphs, pages 66, 70, 80, 81, 83. The census for these households was recorded between 25-28 July 1624. The soprannome ‘del Min’ died out within the first couple of generations after the census was taken.

[x] Revò parish archives, anagraphs, page 83-84 (Revò, 31 July 1624).

[xi] Giulio Floriano was born 19 September 1654. Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 314-315. We will look at him again when we discuss nobility.

[xii] This chart was made using Family Tree Maker software (2019 version).

[xiii] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Inventario’. 15 July 1537, Cloz. Inventory of the church of San Stefano of Cloz drafted in abbreviated form by notary Giorgio Rovina, with the final draft made later by Giuliano, son of Federico Magagna of Revò, notary. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/2196657. Accessed 12 March 2024.

[xiv] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Estinzione di debito e costituzione di censo.’ 2 November 1563, Rivo (Brez). Debt dissolution and land lease agreement drafted by notary Giuliano, son of the late Federico Magagna, of Revò. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/957167. Accessed 12 March 2024.

[xv] See APPENDIX for list of pergamene that bear his notary seal.

[xvi] STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 216.

[xvii] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Compravendita’. 3 September 1613, Revò. Before Ferdinando Ferrari of Revò, delegated by Francesco Benassuti, assessor of Valli di Non and Sole, donna Rosa, wife of Giorgio Magagna, in the presence of her husband, sells to don Vigilio Manincor of Revò, pievano of (Vigo) Lomaso, part of the living room of the house of the said Giorgio, for a price of 22 ragnesi. Drafted by notary Federico Magagna of Revò, with countersignature of notary Giacomo Aliprandini of Livo. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1015312 . Accessed 12 March 2024.

[xviii] ARCHIVIO DI STATO DI TRENTO, APV Sezione Latina. Capsa 9, 169 1620 Tax Census, Revò, page 3. Recorded 30 September 1620.

[xix] Revò parish archives, anagraphs, page 83-84 (Revò, 31 July 1624).

[xx] Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 82-83.

[xxi] Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 56-57.

[xxii] The earliest record where I have found him called ‘spectabilis’ is the baptismal record of his eldest son Giovanni Girolamo on 22 Aug 1693 (Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 366-367).

[xxiii] Revò parish records, deaths, volume 2, no page number.

[xxiv] Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 66-67.

[xxv] Revò parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number.

[xxvi] Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 82-83.

[xxvii] See APPENDIX for a list of several of the pergamene he drafted within that timeframe.

[xxviii] Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 298-299. Pietro was born 20 December 1652.

[xxix] WIKIPEDIA. ‘Doctor of Divinity’. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doctor_of_Divinity . Accessed 29 March 2024.

[xxx] SEGARIZZI, Arnaldo (Dott). 1909. ‘Professori e scolari trentini nello studio di Padova’ (continuazione). Archivio Trentino, Anno XXIV (1909), Fasc. III (Vol 3), page 247.

[xxxi] She is sometimes referred to as Anna Maria. The marriage record is not in Revò parish records. She died 3 April 1715 (Revò parish records, deaths, volume 2, no page number), more than 30 years after her husband passed away.

[xxxii] Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 156-157.

[xxxiii] Revò parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number.

[xxxiv] Giulio Floriano was born 19 September 1654 (Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 314-315).

[xxxv] Revò parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number.

[xxxvi] Giuseppe Andrea (born 1 December 1695), Girolamo (born 22 August 1700), and Maria Cristina (born 8 March 1705). Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 394-395; page 448-449; page 496-497.

[xxxvii] I did find a noble Magagna listed on website for the Tiroler Landesmuseen, but it says they were from Rovereto, and I cannot find any connection between them and this noble line of Revò. My guess is that this Rovereto line might actually have been from the region of Veneto, where the surname is fairly prominent, and where there was apparently a noble line (although their city of origin seems to be disputed amongst scholars for that region). TIROLER LANDESMUSEEN. ‘Magagna’. Tyrolean Coats of Arms. Accessed 16 March 2024. https://wappen.tiroler-landesmuseen.at/index34a.php?id=&do=&wappen_id=19247&sb=magagna&sw=&st=&so=&str=&tr=99.

[xxxviii] He died 08 September 1712 (Revò parish records, deaths, volume 2, no page number). I did find a peripheral reference to a noble Giacomo, son of Giovanni, in 1768, but I have found no children for that Giacomo, nor have I been able to identify who his father was.

[xxxix] The couple married in the church of San Vitale in Romallo on 4 June 1679 (Revò parish records, marriages, volume 1, no page number).

[xl] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Locazione di decima’. 21 April 1696, Castel Valer (Tassullo). Count Girolamo Spaur gives one-quarter of the rights to the decima of Romallo to Giovanni Magagna, son of the late Tommaso Magagna of Revò, living in Romallo, for a period of 7 years, for an annual rent of agreed quantities of wheat, ray, and farm animals. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/991177. Contains multimedia (photocopy of original document). Accessed 12 March 2024. Identical entry also at https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/991172.

[xli] Filippo Giovanni Battista Magagna (born 26 March 1804, Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 5, page 420-421) married the much younger Maria Domenica Illuminata Pancheri (born 28 November 1813, Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 6, page53) on 20 March 1833 (Revò parish records, marriages, volume 3, page 123-124).

[xlii] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez. Fondo: Litotipo Anaune, page 247.

[xliii] Photo from RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez. Fondo: Litotipo Anaune, page 129.

[xliv] Parchments cited in RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez. Fondo: Litotipo Anaune, page 247. He mentions their son Pietro in a document dated 9 Feb 1599, and son named Giovanni who became a priest, mentioned in a document dated 2 January 1626.

[xlv] Arsio e Brez parish records, marriages, volume 2, page 98-99.

[xlvi] Giovanni was born in Brez on 20 April 1714. Arsio e Brez parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 442-443.

[xlvii] Maria Anna was born 8 February 1716. Arsio e Brez parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 460-461.

[xlviii] Arsio e Brez parish records, marriages, volume 2, no page number.

[xlix] RUFFINI, Bruno. 2005. L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez. Fondo: Litotipo Anaune, page 247.

[l] The couple married in Castelfondo on 1 February 1619 (Castelfondo parish records, marriages, volume 1, no page number). Giovanni Antonio was born in Brez on 05 March 1591 (Arsio e Brez parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 19).

[li] Arsio e Brez parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 89.

[lii] The couple married on 21 December 1649 (Castelfondo parish records, marriages, volume 2, no page number).

[liii] Flora Magagna was born in Castelfondo on 02 October 1651 (Castelfondo parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 23-24). She would have died in infancy, as another daughter of the same name was born on 30 May 1657 (Castelfondo parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 39-40).

[liv] Giovanni Genetti, miller, was deceased before his wife Maria died on 30 March 1648 (Castelfondo parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number), and his death record does not appear in the register that begins in 1641.

[lv] Bartolomeo died 23 April 1671 (Castelfondo parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number).

[lvi] Giovanni Battista was born 24 April 1662 (Castelfondo parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 51-52), and died 13 January 1704 (Castelfondo parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number). His death record says he was a miller.

[lvii] Giovanni Battista married Lucia ‘Lanza’ Genetti of Castelfondo on 20 Jan 1693 (Castelfondo parish records, marriages, volume 2, page 31).

[lviii] Castelfondo parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 51-52.

[lix] Stefano died in Castelfondo on 19 January 1672

[lx] Castelfondo parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 71-72.

[lxi] Giacomo Antonio Magagna of Castelfondo, ‘age 34’, a miller, died on 16 June 1701. Castelfondo parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number.

[lxii] Giacomo Antonio Magagna and Margherita Turra (daughter of Nicolò) married 11 September 1696 (Castelfondo parish records, marriages, volume 2, page 35).

[lxiii] Stefano Magagna and Domenica Genetti married in Castelfondo on 24 November 1717 (Castelfondo parish records, marriages, volume 2, page 50).

[lxiv] Clemente Magagna was born 9 March 1725 (Castelfondo parish records, baptisms, volume 3, page 8-9).

[lxv] Clemente Magagna and Margherita Turra (daughter of Francesco) married 23 November 1745 (Castelfondo parish records, marriages, volume 2, page 72). Margherita was born one of twin girls on 31 December 1725 (Castelfondo parish records, baptisms, volume 3, page 12-13).

[lxvi] We infer they died, as Clemente had children with the same names born later. However, there are very few death records for infants in the parish records for Castelfondo in this era.

[lxvii] Margherita Turra died in November 1749 (Castelfondo parish records, deaths, volume1, no page number). The precise date is not recorded.

[lxviii] The couple married in Castelfondo on 27 January 1751 (Castelfondo parish records, marriages, volume 2, page 77).

[lxix] Stefano’s death record actually says he was 26, but this is surely an error, as the earlier Stefano (born in 1748) would certainly have died before he was born. Castelfondo parish records, deaths, volume 2, page 46-47.

[lxx] Maria Segna, widow of Clemente Magagna, died in Castelfondo on 30 December 1807 (Castelfondo parish records, deaths, volume 2, page 168-169. The death record says she was about 80 years old, but she was younger.

[lxxi] Revò parish archives, anagraphs, page 79-80 (Revò, 28 July 1624).

[lxxii] The last Magagna male from this line was Gervasio’s great-great-grandson Nicolò, who died at the age of 12 on 04 September 1746 (Fondo parish records, deaths, volume 2, no page number).

[lxxiii] Fondo parish records, marriages, volume 1, no page number.

[lxxiv] Arsio e Brez parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 318-319.

[lxxv] Giacomo Magagna of Brez died 3 Dec 1697. Arsio e Brez parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number.

[lxxvi] Adamo Magagna died in Fondo on 20 April 1743. Fondo parish records, deaths, volume 2, no page number.

[lxxvii] Dambel parish records, baptisms, volume 1, no page number.

[lxxviii] Dambel parish records, baptisms, volume 1, no page number.

[lxxix] Maria Giacoma, wife of Giuliano Magagna, is cited as a godmother on 20 September 1631 (Dambel parish records, baptism, volume 1, no page number).

[lxxx] Giuliano Magagna and Margherita Gentilini married 04 May 1633 (Revò parish records, marriages, volume 1, no page number). His father’s name is not mentioned in the record, but he is said to be a widower. Margherita’s father’s name is not in the record, but the only Margherita Gentilini in the 1624 Romallo census is the daughter of Federico, who was said to be 14 years old at the time of the census (Revò parish archives, anagraphs, page 91-92 (Romallo, 4 August 1624)). Thus we can estimate she was born around 1610, and that she was about 23 years old when she married.

[lxxxi] Margherita, wife of Giuliano Magagna, cited as godmother of Domenica Bettini on 23 December 1633. Dambel parish records, baptisms, volume 1, no page number.

[lxxxii] Her name may actually have been ‘Libera’, but she appears as ‘Libra’ in the majority of records.

[lxxxiii] Lorenzo was born 28 May 1636, and Giorgio on 12 August 1642 (Dambel parish records, baptisms, volume 1, no page number).

[lxxxiv] Dambel parish records, baptisms, volume 1, no page number.

[lxxxv] Dambel parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number.

[lxxxvi] FANTELLI, Udalrico; PODETTI, Pietro; FERRARI, Salvatore. 2008. Commezzadura: Storia, Comunità, Arte. Comune di Commezzadura, page 189-190.

[lxxxvii] The two men were more commonly known as ‘Federico’ and ‘Giacomo’, respectively.

[lxxxviii] FANTELLI, Udalrico; PODETTI, Pietro; FERRARI, Salvatore. 2008. Commezzadura: Storia, Comunità, Arte. Comune di Commezzadura, page 189-190.

[lxxxix] STENICO, P. Remo. 2000. Sacerdoti della Diocesi di Trento dalla sua Esistenza Fino all’Anno 2000. Indice Onomastico, page 255.

[xc] FANTELLI, Udalrico; PODETTI, Pietro; FERRARI, Salvatore. 2008. Commezzadura: Storia, Comunità, Arte. Comune di Commezzadura, page 251.

[xci] FANTELLI, Udalrico; PODETTI, Pietro; FERRARI, Salvatore. 2008. Commezzadura: Storia, Comunità, Arte. Comune di Commezzadura, page 251.

[xcii] FANTELLI, Udalrico; PODETTI, Pietro; FERRARI, Salvatore. 2008. Commezzadura: Storia, Comunità, Arte. Comune di Commezzadura, page 251.

[xciii] Segonzano parish records, marriages, volume (?), page 215.