Genealogist Lynn Serafinn discusses the medieval origins of the Stanchina family, and how its branches in Livo, Terzolas and Carciato are ancestrally connected.

This article is also available as a 31-page downloadable, printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, charts, maps, footnotes and resource list. Price: $3.25 USD.

CLICK HERE to buy this article in the ‘Digital Shop’, where you can also browse for other genealogy articles.

I love researching the history and origins of our Trentino surnames. But sometimes, there is something about a surname that will make me curious to dig more deeply than I normally would. It doesn’t even have to be a surname from my own family tree. More often, it is a surname I stumbled upon when doing research for a client.

Perhaps I found the sound of the surname to be interesting, or perhaps its sound or linguistic origin is unique amongst others in the province. Or perhaps the surname is ‘imported’ either from outside the province, or from a different part of the province. In such cases, the obsessive genealogist in me will want to verify whether different families with that surname are ultimately descended from the same patriarch. I will want to discover the precise point of entry – the who, where and when of the first person who brought that surname to the province, or to that village.

Lastly, I am often drawn to study families who have been ennobled. This is not because I am attracted by noble titles, but because I know I will be more likely to find their names in legal documents that pre-date the beginning of the parish registers. Generally, I’m not so interested in the very highest-ranking nobles, such as the Counts of Tyrol. Firstly, many volumes have already been written about the Counts of Tyrol by other historians; secondly, while many of my clients have noble ancestors, I’ve yet to have a client descended from a Count (at least not ‘legitimately’).

The surname STANCHINA meets many of these criteria. It has an unusual sound, and it is not closely similar to most other Trentino surnames.[1] Although the surname appears to have originated within the province, many branches arose as a result of migration over the centuries, making it an intriguing genealogical puzzle to piece together. And finally, many lines were considered nobility, some attaining the rank of Knights of the Holy Roman Empire. Lastly, a few of my clients have ancestors with this surname, meaning I had the added motivation to share a history of their ancestors with them, and show them how they are all ‘cousins’, even if only distantly.

But doing such a study does not come without its challenges. Surnames as we know them did not really exist before around the beginning of the 1400s (and early surnames were often somewhat ‘fluid’), and parish records did not begin until the latter half of the 1500s. Thus, weaving your way back in time to find the precise origin of a particular surname is often difficult, and may not always yield the answers you seek.

The Aims of this Article, and the Sources Used

In this article, I will aim to identify the origins of the Stanchina lineage, and to illustrate how various branches of the family migrated and expanded over the centuries.

As the parish registers will only come into play from the late 1500s (and, in some cases, early 1600s), any information about their more ancient history has been gleaned mainly from surviving legal parchments, also called ‘pergamene’ (singular = ‘pergamena’). Most of the pergamene I have cited were taken from in the 3-volume work entitled Inventari e Regesti degli Archivi Parrocchiali della Val di Sole by Giovanni Ciccolini. Others were attained from other published inventories or from the Archivi Storici del Trento database. Most of the information about nobility has been gathered from published books that refer to diplomas and lists held in the State Archives in Trento or Innsbruck. You will find all endnotes and resources at the end of the article.

All genealogical charts in this article were made by me, drawn from a ‘Stanchina Master Tree’ I have constructed using Family Tree Maker software. This tree is a composite of all research I have done independently using the sources mentioned above, with some items drawn from writings of other published histories.

Geographic Origins and Expansion of the Stanchina

In most books published before 2010 or so, you will read that that Stanchina were originally from Terzolas in Val di Sole.[2] [3] [4] [5] However, more recent research has convincingly demonstrated that the family originally came from (or at least lived in) Tassullo in Val di Non, and then moved to Livo, which lies at the junction between Val di Non and Val di Sole. From Livo, a branch of the family relocated to settle in Terzolas.[6] [7] The most recent branch is that of Carciato (also in Val di Sole), which began when a member of the Terzolas line relocated there in the 18th century. Throughout this article, we will be examining all of these branches, with an aim of reconstructing a genealogical link between them.

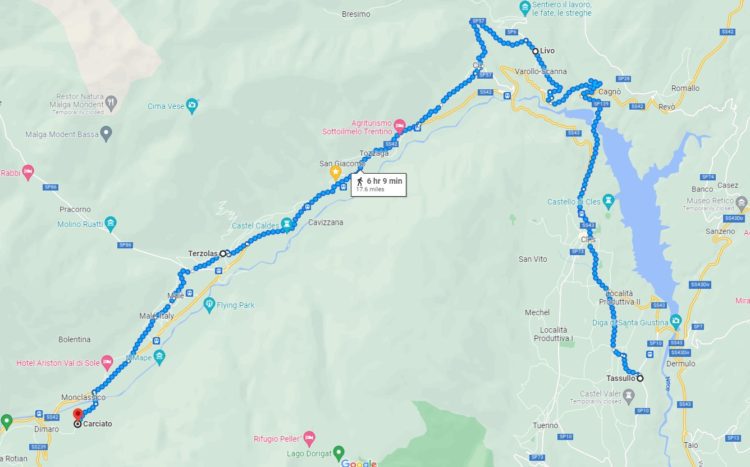

To get a feeling for what the migration pattern looked like, here is a street map starting in Tassullo to the southeast, then looping northward to Livo, then southwest towards Terzolas, and finally to Carciato:

IMAGE: Street map from Google Maps showing of journey (on foot) from Tassullo, to Livo, Terzolas, and Carciato. Click image to see it larger.

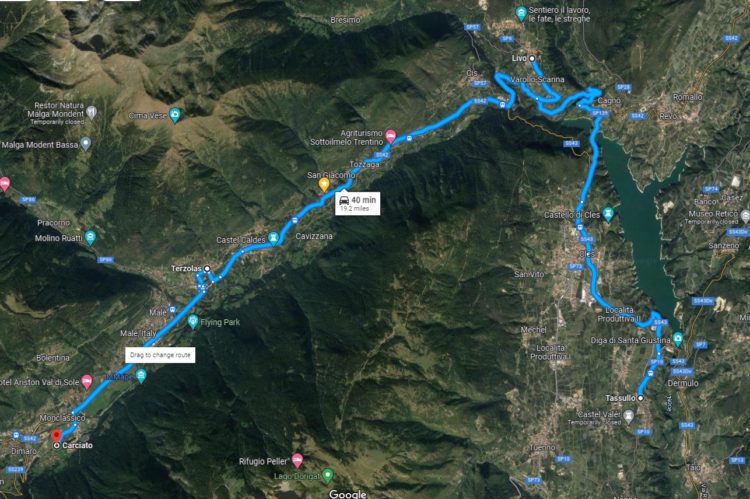

What this type of map does not show, however, is why this journey was shaped so peculiarly. When we look at the same journey on a map showing the terrain, we can see it ‘hugs’ the outline of mountainous, densely forested, and essentially uninhabitable area. Even if you were driving in a car today, you would still need to made this somewhat zig-zagged, inverted U-shaped journey:

IMAGE: Terrain map from Google Maps showing of journey (by car) from Tassullo, to Livo, Terzolas, and Carciato. Click image to see it larger.

Unconvincing Linguistic theories

Spelling variants: Stanckhini; Staigkin; Stanken; Staiken; Stanghin.

Nobility variants: Stanchina von Panienthurm um Leiffenburg; Stanchina Panianthurn zu Leiffenburg; Stanchina de Torre de Pegnana.

The linguistic origins of a surname can often tell us much about the history of the family. But in the case of the Stanchina, many of the published theories about its linguistic are unconvincing, if not altogether incorrect.

Bertoluzza[8] proposes the surname may be derived from the eastern European name ‘Stanislav’. Alternatively, both he and Leonardi[9] suggest it is a patronymic derived from the medieval personal name ‘Stancario’, which has been found in documents as early as 973. But these linguistic theories do not stand up against what we now know about the actual history of the Stanchina family in Trentino. If the surname were a patronymic, then you would find a patriarch with that personal name who lived just before the surname was adopted. As we will see shortly, there is no ‘Stancario’ to be found among the ancestors of the man we now know as the ‘first’ Stanchina in Tassullo.

Another possibility is that Stanchina is a toponymic surname, i.e., one derived from the name of a place associated with the founding family. Bertoluzza comments there once was a locality known as ‘Stanchini’, but he does not say where it was,[10] and none of my own investigations led me to information on a place with this name. Moreover, in none of the early documentation do we find the family mentioned in connection with a place with a name resembling Stanchina.

As the word does not resemble an occupation, the last possibility is that it was a soprannome, used as a nickname describing Nicolò’s personal attributes. In modern Italian, the word ‘stanca’ is the feminine form of and adjective meaning ‘tired’, and the diminutive ‘stanchina’ might be interpreted as ‘tired little girl’, which of course makes no sense at all. Leonardi says the word ‘stancario’ refers to a lance or a spear,[11] but connecting it to the surname seems a bit of a stretch to me.

Thus, for now, I feel the linguistic origins of the surname must remain a mystery. But happily, we know much more about the family’s activities in this late medieval era.

The First ‘Stanchina’ and His Possible Ancestry

According to Guelfi, early forms of the surname – Stankin, Stainken, Stangehin – appear in documents from the 1300s.[12] Ausserer says the same, but lists completely different variant spellings – Staubin, Staickin, Stangkin.[13] However, neither author cites his sources, or tell us where the family lived, or whether these examples are from the early, middle or latter part of the century. So, without more information, I cannot comment or assess their relevance.

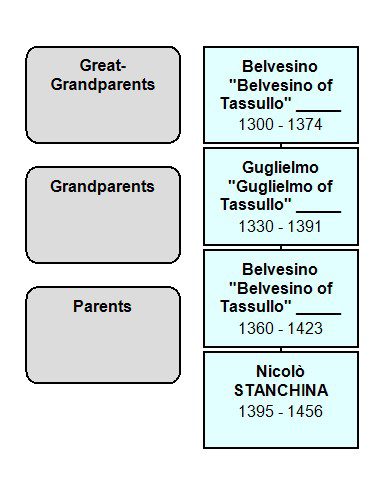

We do have some concrete documentary evidence of the surname appearing in the early 1400s, however. In a legal agreement dated 28 April 1423, held in the Thun Archives in Castelfondo, we find amongst the witnesses to the transaction a ‘Nicolò called “Stanchina”, son of Ser Belvesino di Tassullo, now living in Livo’.[14] [15] This is, to the best of my knowledge, the earliest surviving document containing the surname (or at least the designation) ‘Stanchina’. As we find out more about this Nicolò and his descendants, it become apparent that he was the patriarch of all the Stanchina branches that would eventually flourish in Livo, Terzolas and Carciato, and other places in the province.

In his list of Trentino notaries, P. Remo Stenico mentions a as ‘Belvesino (‘Belvesinus’), son of the late Guglielmo of Tassullo’, who appears in a document dated 1391.[16] Historian Paolo Odorizzi believes this to be the previously-mentioned Belvesino of Tassullo, who was the father of Nicolò Stanchina.[17] As the surname was not yet in use, this is admittedly somewhat speculative, but I am inclined to agree with Odorizzi that Belvesino, the father of Nicolò, and Belvesino, son of Guglielmo, are one and the same person. If that is true, then it takes us back one more generation, to Guglielmo of Tassullo. From this point, Odorizzi tells us of a ‘Ser Guglielmo, notary, son of Ser Belvesino of Tassullo’, who is named as a witness in a notary document dated 11 March 1374.[18]

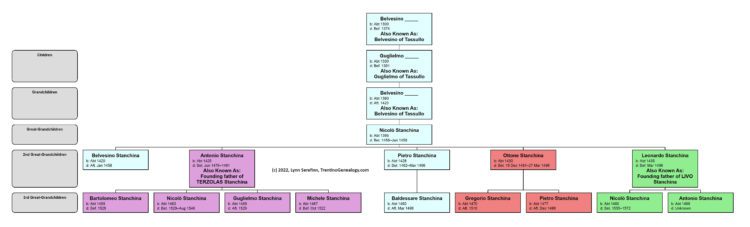

Based on these documents (and others cited by Odorizzi), we can construct a 4-generation tree, outlining the paternal lineage of Nicolò Stanchina of Tassullo back to around the year 1300:

Possible Links to the Thun Family?

To readers who may be familiar with the history of medieval Trentino, the name ‘Belvesino’ may have already caught your attention. Castel Thun, the formidable and majestic residence of the noble Counts of Thun (which, today, is just as formidable a museum), was originally called ‘Castel Belvesino’. In the High Middle Ages, before surnames were commonly in use, many people (including nobility) would be referred to by the name of their place of residence. Thus, as ‘Belvesino’ is such an uncommon name, and one directly associated with the Counts of Thun, it would not be too far-fetched to imagine he had some familial connection to the Thun family. Moreover, it is significant that we see the title ‘Ser’ recurring in this line, which is an honourific generally reserved for nobility.

This is precisely the theory by Paolo Odorizzi in his book Val di Non e i Suoi Misteri, wherein he proposes that Belvesino (the elder) was a son of an illegitimate son (Corrado, called ‘Buscacio’) in the noble family of Castel Belvesino, who would later be known as ‘Thun’. As his argument is very complex, and as I have not personally reviewed the documents from which has sourced the information, I refer the reader to pages 461-484 of that book for further consideration.[19]

Investiture at Mostizzolo

We return now to Nicolò Stanchina and move forward in time to see how the family evolved over the coming centuries.

In 1435, the Prince-Bishop of Trento Alessandro di Mazovia (reigned 1423-1444), invested Nicolò Stanchina with the Office of Massaro in the fief (‘feudo’) of Mostizzolo.[20] This fief intitled Nicolò to the use of all the fields, pastures, vineyards, etc., in that property, and also to a portion of the taxes collected from the same. Nicolò’s role as debt collector is evident from a parchment in the Stanchina family archives in Livo dated 13 June 1442, in which Cardinal Alessandro tasks Nicolò with the job of obtaining long overdue payments in the area.[21]

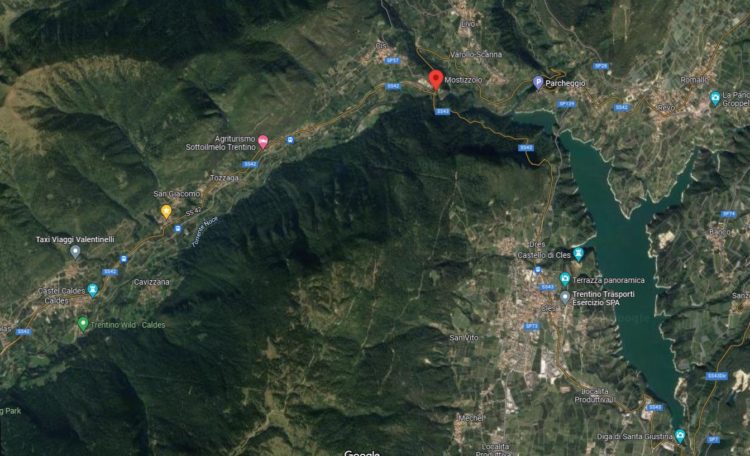

Aside from the income made from working the lands, and the profits the Stanchina were permitted to draw from taxes, the investiture at Mostizzolo had other assets that can only be understood by looking at where it is located:

IMAGE: Terrain map from Google Maps showing location of Mostizzolo. Click on image to see it larger.

The location of Mostizzolo was highly desirable, as it is positioned at the ‘apex’ of that inverted U-shaped journey we saw in the earlier maps, precisely at the junction between Val di Sole (running to the southwest) and Val di Non (to the south and east, on both sides of Lago di Santa Giustina). This made Mostizzolo an important crossing point for trade between the two valleys. Its geographical position also made it an important military stronghold; in fact, it was the site of a fortress, which had stood there since the 1100s. Thus, being granted this investiture was no small stroke of fortune for the Stanchina.

The Stanchinas’ feudal privileges at Mostizzolo were unfortunately short-lived, however, as the next Prince-Bishop (Giorgio de Hack) transferred the fief of Mostizzolo to Vigilio of the Counts of Thun in 1447. The Thun, who had been keen to possess this valuable military and economic strategic point for themselves, retained control over Mostizzolo until the Napoleonic invasions in 1789.[22]

Article continues below…

The Five Sons of Ser Nicolò of Livo

In 1456, Ser Nicolò (who had by now acquired citizenship of Livo), purchased two houses in Pedergnana (Val di Rabbi), but was deceased by January 1458, leaving behind 5 sons: Antonio, Belvesino, Leonardo, Ottone and Pietro, who were all still living in their paternal home in Livo.[23]

Of these, Belvesino may have died soon after, as we have no further information about him.

Pietro Stanchina, who stayed in Livo, practiced the profession of a notary at least between the years of 1458-1462,[24] but absence of other records indicates he may have died relatively young (under 40), leaving behind at least one son (Baldassare), whom we find alive in 1496. None of the sources I have consulted mention whether Baldassare had sons who carried on the family name.

Leonardo, who also remained in his ancestral home of Livo, is the founding father of the Stanchina family of LIVO, as all of those lines can be traced back to him.

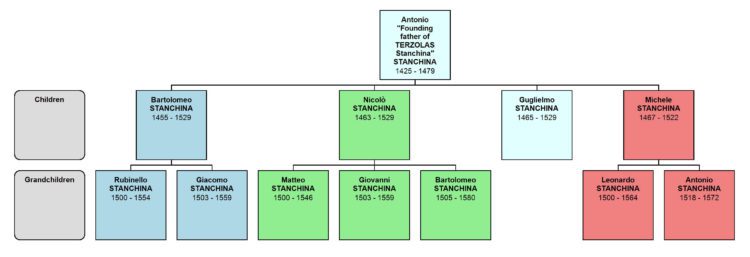

Antonio left Livo to establish his residence in Terzolas and became the founding father of the Stanchina line of TERZOLAS. Again, all the Stanchina of Terzolas can be traced back to him. In the early 1700s, a branch from this line established itself in Carciato, making him the ancestral patriarch for that line as well.

Finally, we look at Ottone Stanchina, who appears to have been the longest lived of the five brothers. By 1470, he had transferred to the parish of Malé, which then included the areas of Samoclevo and Terzolas.[25] HIs aristocratic career was long and illustrious. In a land sale agreement, in Terzolas, dated 23 March 1491, we learn that ‘Ser’ Ottone, son of ‘Ser’ Nicolò Stanchina of Livo was Captain of Castel Rocca in Samoclevo, under the authority of the noble Giacomo Thun.[26] We see him performing a similar transaction on behalf of Antonio Thun on 3 December 1493.[27]

Sometime before 27 March 1496, Ottone passed away, as the noble Pangrazio Spaur then passes the investiture of Castel Rocca to Bartolomeo Stanchina, son of Ottone’s late brother Antonio. [28] This document stays Ottone had been granted the investiture on 15 December 1491, although we know from the other documents already cited that he was already Captain of Castel Rocca by March 1491 (so I can only presume the document from December 1491 was some kind of update on his previous investiture).

This 1496 investiture is particularly rich in genealogical information. It tells us that, in 1491, Ottone had obtained the investiture in 1491 not only for himself, but also on behalf of his nephews – the sons of his deceased brothers, Pietro and Leonardo. While we are told that Pietro’s son was named Baldassare, the names of Leonardo’s sons are not mentioned (although it says ‘brothers’, indicating there was more than one), possibly because they were still children.[29] The document further tells us that now, in 1496, Bartolomeo Stanchina is appealing for the investiture on his own behalf, as well on the behalf of the same Baldassare (son of the late Pietro) and ‘the Stanchina brothers’ (sons of the late Leonardo) granted the investiture in 1491, as well as Pietro, son of the late Ottone.[30] This is the only mention of Ottone’s son Pietro I have found in any record, and I have no further information about it.

The late Ottone’s name appears in a later document from 1510, which mentioned his ‘biological’ son, Gregorio, who was living in Caldes.[31] The terms ‘biological son’ infers Gregorio may have been illegitimate; indeed, the fact that he was not represented by Bartolomeo Stanchina in the 1496 investiture document also seems to indicate he was not considered to be a legitimate heir.

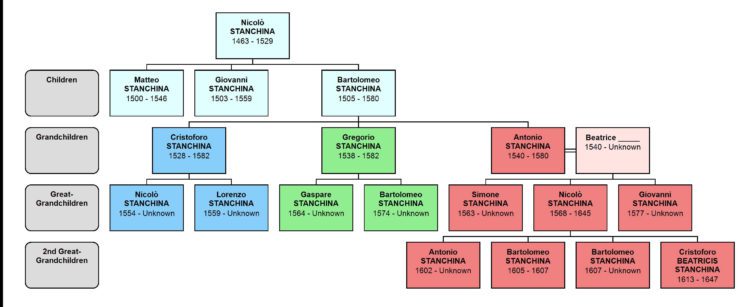

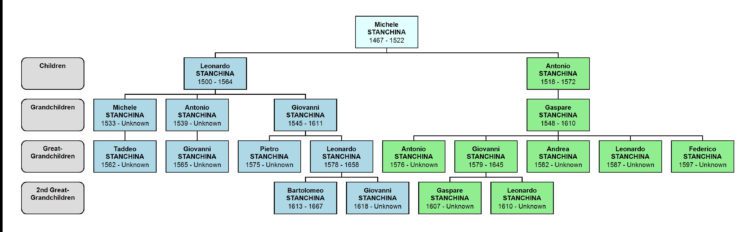

Overview of Early Stanchina Generations

To summarise what we’ve just discussed, and before moving on to look at the development of the Stanchina lines in Livo, Terzolas and Carciato, here is a genealogical chart showing the first five generations of Stanchina men known to be descended from Belvesino of Tassullo:

Click on the image to see it larger.

I made this chart after constructing a tree in Family Tree Maker, inserting estimated dates of births, marriages and deaths, using the compiled information I have gathered so far.

In green, I have highlighted Leonardo, the ‘Founding Father of the Livo Stanchina’, and his sons.

In purple, I have highlighted Antonio, the ‘Founding Father of the Terzolas Stanchina’, and his sons, who is also the patriarch of the Carciato line.

Stanchina of Livo (1510-1600)

We start our discussion on the specific branches of the Stanchina by looking at the family that remained in Livo, descended from Leonardo (son of ‘Ser Nicolò), the ‘founding father’ of the Livo line.

As the baptismal and marriage records for Livo do not begin until the 1570s, we must again draw upon notary parchments for our information about the earlier generations of this family. We already learned from the investiture documents of 1491 and 1496 that ‘Ser Leonardo’, then deceased, had more than one son. My research has uncovered only two – Nicolò and Antonio – who were alive after those dates.

Nicolò and Antonio, Sons of Leonardo

Nicolò’s name is especially prominent in the pergamene, as he had a long career as a notary at least between the years 1510–1555,[32] and his signature appears in numerous legal documents. While many of his signatures say he was ‘son of the late Ser Leonardo Stanchina’, some also specify that he was also the grandson of ‘Ser Nicolò’.[33] [34] As we can assume he was a legal adult (25 years or older) when he began his practice, we can estimate he was born no later than 1485, and that he was probably in his 70s when he passed away (Livo death records do not begin until 1658).

The earliest document in which I have found a reference to Antonio is a land sale agreement drafted on 2 January 1513, where ‘Antonio Stanchina, son of the late ser Leonardo Stanchina’ is cited as witness.[35] Being a legal witness most likely means he was then of majority age (25 years or older), thus born no later than 1487.

We can conclude from this that both Nicolò and Antonio were the ‘brothers’ referred to in the investiture document of 1491, although there may have been other siblings for whom we have no evidence.

Rural Nobility (1529)

After the so-called ‘Guerra Rustica’ (Rustic War) of 1525, many families in Val di Non and Vale di Sole who remained loyal to the Prince-Bishop, who was then Cardinal Bernardo Cles, were granted a title of ‘rural nobility’ in 1529. We are fortunate to know many (if not most) of these names, as the notary Giuseppe Sandris of Nanno[36] compiled them into a Catalogue of Rural Nobility of Valli di Non and Sole in 1529 (albeit many entries are somewhat vague). Under the listing for rural nobility in Livo, as transcribed by Guelfi, we find both brothers:

The word ‘notaio’ means ‘notary’; although Nicolò is not mentioned by name, he is the only Stanchina notary living in Livo in this era, and it definitely refers to him.

The Descendants of Giovanni, son of Nicolò

I have found no evidence of descendants for Antonio. We know, however, that the notary Nicolò had at least one son, namely Giovanni, who is cited as the ‘son of the late Nicolò Stanchina di Livo’ when he is a witness at the drafting of a land sale agreement recorded on 31 March 1572.[39]

Giovanni had at least three sons (Nicolò, Antonio and Matteo) and a daughter (Anna), who were all born before the beginning of the Livo parish records, but whose names and connection to their father are documented in pergamene, and in later baptismal or marriage records for their children. His sons Antonio and Matteo were especially prolific, both having no fewer than 10 children each between about 1577 and 1609 (albeit many died in infancy/childhood). [40]

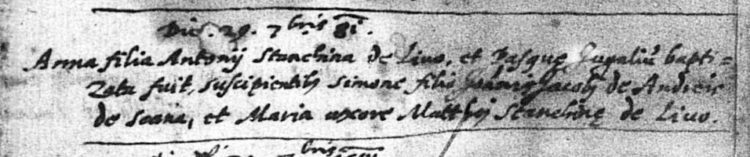

Although we know Antonio had a son named Nicolò who was born before the parish records begin in 1579, the first recorded child for him and his wife Pasqua (or for any Stanchina in Livo, for that fact) is dated 29 Sept 1581, for a daughter named Anna.[41] Note also that Anna’s godmother was Maria, the wife of Antonio’s brother, Matteo:

Click on image to see it larger.

As Antonio was already married before the beginning of the parish records, we do not know the surname of his wife, Pasqua. But we do know that on 19 January 1579, Matteo married Maria Aliprandini, a young daughter of the notary Aliprando Aliprandini of Preghena.[42] Based in Preghena, the Aliprandini were another affluent, noble family, renowned for producing dozens of notaries throughout the centuries.[43] The closeness of these two families is evidenced by a document dated 28 July 1583, in which ‘Matteo, son of the late Giovanni Stanchina, and the heirs of Aliprando Aliprandini of Preghena’ are jointly invested with the use of several fields and pasturelands.[44] There are similar examples connecting these two families in later generations.

Here we begin to see how, through intermarriage, the Stanchina would ultimately establish a strong network of family (and business) connections not just with the Aliprandini, but also with other many influential and aristocratic families, in the centuries to come.[45]

Following tradition, Matteo and Maria named their first son after Matteo’s father, Giovanni, and their second son after Maria’s father, Aliprando. After that Aliprando apparently died in infancy, they had another son named Aliprando in 1598.[46] This is the first time we find a Stanchina with the name Aliprando, but from this point forward, we will find this name recurring numerous times amongst Aliprando’s descendants, at least into the mid-1700s, an enduring reminder of their connection to the Aliprandini family in the past.

Knighthood – The Stanchina de Leiffenburg (1624-1661)

We know from many sources that, in 1624, the Stanchina of Livo were elevated to the grade of Knights of the Holy Roman Empire (Cavalieri del S.R.I.), granting them the right to use the predicate ‘de Leiffenburg’ (sometimes ‘von’ is used instead of ‘de’), which is German for ‘Castel Livo’. [47] [48] [49] [50]

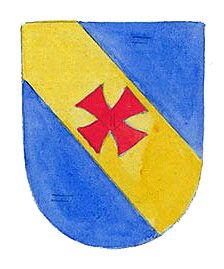

The original stemma (coat-of-arms) awarded to the Stanchina in 1624 was a blue shield with a vertical band of gold.[51] [52] Many variations of this original stemma appear in books, the primary difference being the contents of the crest adorning the shied. One key element that appears in all versions of the crest is the pair of blue and gold buffalo horns in the middle. Rauzi comments that the Stanchina ‘boasted’ that they had essentially the same stemma as that of the Counts of Thun, the only difference being the additional elements in the crest.[53] Whether this is merely coincidence or intentional, I cannot say. If intentional, it could possibly indicating an ancestral connection between the two families, as suggested by Odorizzi; alternatively, it could simply have been an expression of a desire to be associated with the Lords of Thun. For comparison, here are two depictions of the Stanchina stemma from 1624, followed by one version of the stemma for the Thun von Hohenstein. The similarity is certainly evident.

ABOVE: 1624 stemma of the Stanchina de Leiffenburg, as depicted by Tabarelli de Fatis and Borrelli. [54]

ABOVE: A more ornate version of the 1624 stemma of the Stanchina de Leiffenburg, as depicted by Rauzi

. [55]

ABOVE: Stemma of Thun von Hohenstein, as depicted by Tabarelli de Fatis and Borrelli

. [56]

This article is also available as a 31-page downloadable, printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, charts, maps, footnotes and resource list. Price: $3.25 USD.

CLICK HERE to buy this article in the ‘Digital Shop’, where you can also browse for other genealogy articles.

Who Exactly Was Knighted?

One thing I find curious (and slightly frustrating) is that none of the sources I have consulted specify the name of the man or men upon whom the title was granted. Unfortunately, the Livo death records do not begin until 1658, so the only way we can determine who was still alive in 1624 is by cross-referencing the parish registers and the scattered parchments. Having done this, I can attest that there were very few adult Stanchina men who were (or may have been) alive in 1624.

One is the afore-mentioned Aliprando Stanchina. We know he died sometime between September 1639 and May 1640, because he is cited as deceased in the baptismal record of his daughter Marina on 24 May 1640.[57] He would have been 26 years old and already a head of a household in 1624. Given these facts, alone with the apparent social advancement and additional noble titles we see later amongst his descendants, he was certainly one recipient of this imperial title.

We know that all the Stanchina men from the generations before his were already deceased (except perhaps his father Matteo[58]), and we know at least three of Aliprando’s first cousins (sons of his uncle Nicolò) were alive in 1624, but they all would have been minors at the time. His nephew Antonio (son of his brother Bernardino) was also still alive, as we see his name in a later document when he is a young man.

To make an educated guess on who exactly had been granted this the diploma of knighthood, let us consider the information from a parchment dated 19 April 1661 in the Stanchina Archives in Livo.[59] This document tells us that on 12 January of the previous year (1660), four Stanchina men had been granted the use of (and profit from) a house and many feudal lands by the Count Prospero Francesco of Spaur, who had since passed away. In this document, his successor Count Giovanni Antonio of Spaur is renewing the investiture, upon which the same four Stanchina men swear an oath of loyalty to their new ‘Lord’.

What makes this document so informative is that is gives the name and paternity of each of these Stanchina men, namely:

- Ser Antonio, son of the late Bernardino Stanchina

- Brothers Matteo and Antonio, sons of the late Aliprando Stanchina

- Nicolò, son of the late Leonardo Stanchina

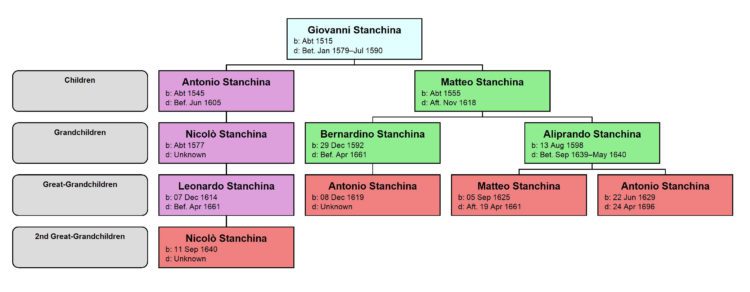

I made this chart to illustrate how all of these men were related:

Click on chart to see it larger.

To make the chart easy to read, I have removed all the mothers and siblings, leaving only the direct male lineage of the four men who were granted the investiture. I have highlighted these four men in orange, with their paternal lines in purple and green, respectively. As per the usual protocol, the four men are listed in the document in order of descending age, starting with the eldest Antonio, son of Bernardino, who was born in 1619.

We already know from the document that Matteo and the younger Antonio (born 1629) were brothers, and sons of the late Aliprando. But here we can clearly see that the elder Antonio was their first cousin, as he was the son of their father’s brother.

The youngest of the four men was Nicolò, son of Leonardo, born in 1640. We can see from this chart that Nicolò’s father Leonardo was the 2nd cousin of the other three men, as they were all great-grandsons of Giovanni Stanchina. This means Nicolò was the 2nd cousin 1X removed of the other three men, as he was born in the subsequent generation.

In my view, I cannot imagine such a significant investiture would have been granted to so many members of this extended family if they were not ALL considered to be of high noble rank. For this reason, I suspect the 1624 Knighthood had been granted either to the ‘heirs of Giovanni Stanchina’, or perhaps (as they would have been more recent in people’s memory) to ‘the heirs of brothers Antonio and Matteo Stanchina’.

Stanchina de Turri de Pegnana (1723)

On 20 April 1723, Prince-Bishop Gian Michele Spaur granted episcopal nobility to Matteo Alessandro Stanchina, granting him the right to use the predicate ‘de Turri de Pegnana’, also see written ‘Torre Pegnana’. [60] [61] The word ‘torre’ means ‘tower’ and ‘Pegnana’ may be a contraction of the place name ‘Pedergnana’ in Val di Rabbi[62], where the Stanchina had owned property since the mid-1400s.

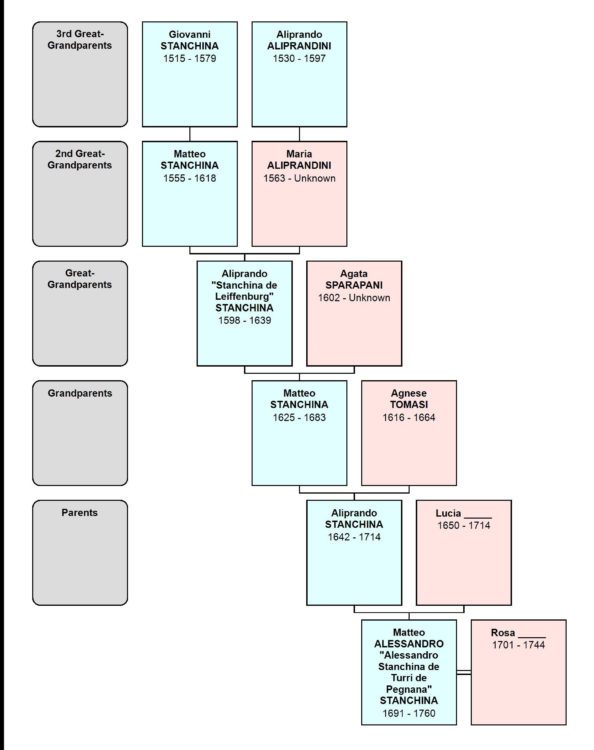

Born in Livo on 11 April 1691, Matteo Alessandro was the son of the noble dominus Aliprando Stanchina of Livo, and his wife Lucia.[63] He was his parents’ eighth child, but their only son, having been born after seven elder sisters.

Click on image to see it larger.

Matteo Alessandro’s Paternal Ancestry

Perhaps, seeing the name ‘Aliprando’ for Matteo Alessandro’s father, you may have already suspected that he was descended from the Aliprando Stanchina de Leiffenburg (grandson of Aliprando Aliprandini), who was knighted in 1624. If so, you would be correct. Below is a chart showing Matteo Alessandro’s paternal ancestral line, with the addition of his 3X great-grandfather Aliprando Aliprandini at the top.[64] Notice how the names ‘Matteo’ and ‘Aliprando’ recur in alternating generations:

Click on image to see it larger.

Due to an unfortunate 80-year gap in the Livo marriage records (1650-1730), I do not currently know anything about Matteo Alessandro’s mother or wife other than their first names.

We do see that his great-grandmother was Agata Sparapani, from the renowned Sparapani family of Preghena who, much like the Stanchina, produced many notaries and had various noble titles throughout centuries.

We ‘met’ his grandfather Matteo earlier, as he was one of the four men who had be granted the investitures of 1660 and 1661. While I know little more about the family of Matteo’s wife Agnese Tomasi (other than her parents’ names), what struck me as most unusual about this couple is that Matteo Stanchina was not quite 15 years old[65] when he married Agnese Tomasi on 26 August 1640.[66] Moreover, Agnese was nearly 9 years his senior, which makes this even more unusual.[67] I have quadruple checked the records and this is no error.

We note, however, that their first child, Aliprando (who would later become the father of Matteo Alessandro), was not born until 21 November 1642, when Matteo would have just turned 18 years old. This does make me suspect that the marriage may have been arranged to create some sort of profitable alliance between the two families, but that the actual consummation of the marriage had been delayed until Matteo was closer to a more ‘acceptable’ marriage age. I have seen other examples of this kind of arrangement, but they usually involve a very young bride (but no younger than 15), rather than a very young groom. The gaps in their ages could also explain why there were no children born after 1656, when Agnese was nearly 40 years old, despite the fact both of them died well after that date.[68] [69]

Another Knighthood. Another Predicate (1764)

According to don Luigi Conter, the Stanchina families continued to increase in both wealth and status throughout the 1700s, while the affluence of several other ancient Livo families – such as the Aliprandini and Anselmi – was steadily declining. [70]

One testament to their increasing influence was the award of yet another knighthood. On 16 January 1764, the three eldest sons Matteo Alessandro – namely Aliprando Michele (born 1724), Giovanni Andrea (born 1726) and Lorenzo Nicolò (born 1728) – were themselves elevated to the rank of Knight, this time being granted the predicate ‘von Panianthurn zu Leiffenburg’, which means ‘of Torre Pegnana e Castel Livo,’[71] thus combining the previous predicates into one. Again, there are many variant spellings for this predicate, depending on whether you are reading German or Italian sources; moreover, Italian sources will always say ‘de’ instead of ‘von’, ‘zu’ or ‘um’). Tabarelli de Fatis and Borelli express that the Stanchina surname in these documents ‘suffered’ many variant spellings (including Staigkin, Stanken, Staiken and Stanghin), undoubtedly due to the language difference between the Stanchina and their German-speaking superiors.[72]

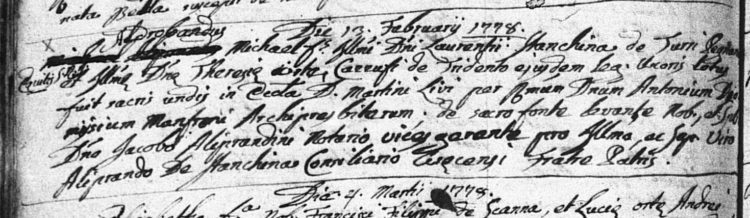

Tabarelli de Fatis and Borelli also tell us that Aliprando Michele was a lawyer in Graz (Austria), and Giovanni Andrea was a Controller of the War Office in Milan. [73] The fact that their occupations took them outside the province is surely why there appear to be no children born to these two men in Livo. Although these same authors say nothing more about Lorenzo Nicolò, my own research has shown that he married the noble lady Teresa Cazzuffi of Trento sometime before 1769, and the couple had at least five children, all born in Livo. Below is this baptismal record for one of their sons, Aldobrando Michele, born 13 February 1778. Two godfathers are listed for the child, the second of whom is Lorenzo Nicolò’s brother Aliprando Michele, who is described as ‘Consiliario Graecansi’, which means ‘Advisor of Graz’.[74]

Click on image to see it larger.

It is likely the child Aldobrando Michele was named after his uncle/godfather, as it appears Aliprando was known as Aldobrando when he lived in Austria, as it is the equivalent name in German.

Eighteenth-century historian and Franciscan priest Giangrisostomo Tovazzi cites a very interesting and somewhat revealing letter, dated June 1775, addressed to ‘the most illustrious Signor Aldobrando Stanchina de Turri Pegnana zu Leiffendorff’ (i.e., Aliprando Michele), who is referred to as ‘Imperial Judge (Giudice Cesareo Regio) and President (or Dean) of the Provincial Civil Court of Trieste’. [75]

Tovazzi tells us this letter was written by Stanchina’s nephew, a young Franciscan monk Lorenzo Zini of Cavareno. Lorenzo (whom Tovazzi refers to as ‘our brother’ as they were from the same religious order), would have been the son of his sister Anna Claudia, who marriage the noble Giovanni Battista Zini in 1747.[76] As Tovazzi would have been Lorenzo Zini’s contemporary, I presume he was allowed to see the letter before it was sent.

Perhaps to honour his Brother Lorenzo’s privacy, Tovazzi does not transcribe the letter the contents of the letter; rather, he inserts his own rather scathing opinion:

(Aldobrando) Stanchina is a native of Livo, whose father was a very wealthy man, though not very civil, whose name was Alessandro. For his eulogy at his funeral, the Archpriest Manfroni of Cles [sic] proposed the theme: ‘The rich man is dead, and he was buried in hell.’[77]

Clearly, neither Father Manfroni nor Tovazzi had a very high opinion of Lorenzo Zini’s grandfather, the noble Matteo Alessandro Stanchina!

Just to clarify, Tovazzi actually says Archpriest Manfroni was from Cles. He was, rather, Archpriest Antonio Dionisio Manfroni from Caldes (born 12 January 1702).[78] He served as the parroco of Livo for 35 years, so he must have known the Stanchina very well. He died at the age of 77, on 12 September 1778, a few years after this letter was written.[79]

Tovazzi closes his comments by telling us that in the year 1788, Aldobrando Stanchina is said to have offered 127 thousand florins to obtain the jurisdiction of Königsberg (which he spells ‘Chinigspergensi’), which included the villages of Lavis, Pressano, Nave, San Michele and Faedo, Giovo, Lisignago, Cembra, Faver and Valda, and constituted a district for the administration of criminal and civil justice. [80]

Changes to the Family Stemma

With the new knighthood granted in 1764, the family stemma went through several changes. The first was the addition of a red cross, set at an angle, placed on the centre of the gold banner:

ABOVE: 1764 stemma of the Stanchina von Panianthurn zu Leiffenburg, Tiroler Landesmuseen, Innbruck. [81] [82]

The crest above the shield was also embellished. Before 1764, it had been comprised of two blue buffalo horns in the centre, with black birdwings to either side, and a gold bar and band on the outer border. After 1764, towers were added in front of the bird wings, and a raised arm holding a silver sword was placed at the top between the buffalo horns:

ABOVE: 1764 stemma of the Stanchina ‘von Panienthurm um Leiffenburg’, as depicted by Leonardi.[83]

Marriages With Other Noble Families

One thing that is striking as we watch the Livo Stanchina throughout the centuries is how they married members of many other noble families – often high-ranking ones – from various parts of the province. Some of those families include:

ALIPRANDINI. You may recall this surname we looked at the descendants of Matteo Stanchina of Livo and Maria Aliprandini (daughter of Aliprando) of Preghena, who married on 19 January 1579.[84] The Aliprandini are a very old and influential noble family from Preghena, who produced many notaries and many priests. Like the Stanchina, a branch would be granted knighthood in the 1700s.

CAPOLINI. About 1807, Matteo Alessandro Stanchina (born 22 December 1764, grandson of the knighted Matteo Alessandro), married the noble Teresa Capolini of Riva del Garda. [85] Teresa’s father was Filippo Capolini de Varonenbach um Brionberg, who had been elevated to the rank of Count of the Holy Roman Empire on 25 August 1790.[86]

MAFFEI. On 25 November 1767, Giovanni Antonio Stanchina (born in Livo 9 December 1721)[87] married the noble Anna ‘Isabella’ Maffei of Romallo.[88] Isabella’s mother was also high nobility, namely Teresa Elisabetta Clara Wielandt from Castelfondo.

SPARAPANI. On 7 February 1622, Aliprando Stanchina (bone 13 August 1598) married Agata Sparapani.[89] I suspect (but am not certain) that Agata came from one of the many ennobled lines in the Sparapani family. We do know that the Sparapani in general were socially affluent family, producing many notaries, with one branch being knighted in 1740.

TORRESANI. While I have not been able to find a marriage record for this couple, all the baptismal records of the children for Antonio Stanchina (born 8 December 1619)[90] and his wife Cattarina Torresani state that she herself is nobility.

ZINI. On 7 Feb 1747, Anna Claudia Stanchina (born 4 August 1730, daughter of Matteo Alessandro) married the noble Giovanni Battista Zini of Cavareno. [91]

I am certain we would see many more such ‘alliances’ in the Stanchina lineage if there were not an unfortunate 80-year gap in the marriage records for Livo. Even so, this gives us an idea of how noble families over the centuries sought to strengthen their wealth and power by forming close ties with other families of similar social influence.

Article continues below…

Stanchina of Terzolas (1478-1529)

In their book Memorie di Terzolas, authors Tiziani Ciccolini and Udalrico Fantelli comment that information about the Stanchina of Terzolas is mainly to be in the ‘occasional notes in the matricular registry of the parish archives of Terzolas’, as well as ‘in the margin notes of curate don Pietro Silvestri,’ a renowned expert in the history of his homeland. They tell us also that don Pietro constructed a family tree the early Stanchina, but they also warn us that this tree contains ‘serious gaps’ and inaccuracies during the period prior to the beginning of the parish registers (which, for Malé, where the Terzolas records were kept at that time, was 1553 for baptisms, and considerably later for marriages and death records). [92]

Thus, without drawing up those notes of don Pietro (which I don’t have at my disposal anyway), let us return to the available pergamene and other references, with an aim of piecing together an early history of the Stanchina in the village of Terzolas.

Recalling our earlier discussion on the five sons of Ser Nicolò Stanchina of Livo, we learned that his son Antonio Stanchina became the founding father of the Terzolas line. Born in Livo (most likely sometime around 1425), we have documentation placing him and his family in Terzolas by 1478.[93] [94]

We also know Antonio had at least four sons – Bartolomeo, Nicolò, Guglielmo and Michele. As all of these sons would have been born well before 1478, I cannot say with certainty whether they were born in Livo or Terzolas. However, as all the records I have found refer to his sons as being ‘of Terzolas’ rather than ‘living in Terzolas’, it is certainly possible Antonio settled in Terzolas around the time he married and started his family, and that his sons were born there.

- We briefly ‘met’ Bartolomeo earlier in this discussion, when he was awarded the investiture of Castel Rocca in Samoclevo in 1496, after his uncle Ottone had passed away. [95]

- We first find Nicolò in a land sale agreement in 1491, wherein he is referred to as ‘son of the late Antonio Stanchina of Terzolas’, [96] thus telling us patriarch Antonio Stanchina was now deceased.

- We know little about Guglielmo, other than the fact he was one of the recipients of rural nobility in 1529, as we will discuss shortly.

- Antonio’s son Michele, who is said to appear in a document from 1501[97], passed away by 1522, when we find various documents referring to ‘the heirs of the late Michele Stanchina of Terzolas’. [98] [99]

Rural Nobility (1529)

As we saw with the Stanchina in Livo, many members of the Stanchina family in Terzolas also were granted the rank of ‘rural nobility’ after the Guerra Rustica of 1525. Again, we refer to Guelfi’s transcription of the list from 1529, wherein the Stanchina of Terzolas who were ennobled are said to be:

Ser Nicolò Stanchina; Guglielmo Stanchina;

Robonello; his brother Giacomo; other, Leonardo.[100]

‘Ser Nicolò and Guglielmo’ at the top of the list are surely the sons of the late Antonio.

We know from the afore-mentioned parchments that Antonio’s son Michele was already deceased by 1522, and the absence of Bartolomeo’s name would surely indicate that he had also passed away before 1529. Thus, by process of elimination, the other Stanchina mentioned must be the sons of either Bartolomeo or Michele, as there simply were no other Stanchina families in Terzolas in this era.

Ciccolini and Fantelli state that we know with certainty that Antonio’s sons Nicolò and Michele had descendants, but they are uncertain about their other two sons.[101] Numerous sources confirm that Nicolò had at least three sons (Matteo, Giovanni, and Bartolomeo), whom we will ‘meet’ a bit later. Regarding the heirs of Michele, I have a couple of theories, which I will discuss below. Regarding the last two brothers – Bartolomeo and Guglielmo – after identifying all the early Stanchina births (and Stanchina as godparents) in the first volume of the Malé baptismal register, and cross-referencing these with legal parchments, I am fairly certain his son Bartolomeo had at least two sons. I also think his son Guglielmo might also have had a son, although I am not yet certain about this.

I believe Giacomo (brother of Robonello) mentioned on list of rural nobility, was the son of the late Bartolomeo. I say this because we know Giacomo had a son named Bartolomeo (most likely born around 1530) [102] who, in turn, named his first son Giacomo (born 18 Oct 1559)[103], as well as a later son (born 13 September 1575), after the first child had died. [104]

Thus, if Robonello (more commonly spelled ‘Rubinello’) was Giacomo’s brother, then he would also be a son of Bartolomeo. The name Rubinello is certainly unusual, but the parish registers do show us a Rubinello Stanchina married with at least three children appearing a generation later in 1560s.[105] I presume this is not the same Rubinello listed in the catalogue of rural nobility, but that he was more likely his son or nephew[106].

Regarding Leonardo, the way his name is recorded by Guelfi (or perhaps in the original document) is slightly problematic. After a semicolon (which indicates a new person), it says ‘altro, Leonardo’, which literally means ‘other, Leonardo’. While I feel safe in interpreting ‘altro’ to mean ‘un’altro’ (i.e., another), we have to query whether this mean ‘another brother of Rubinello (and Giacomo)’ or ‘another Stanchina’?

After comparing many documents and constructing these lines as best I can, I suspect it means ‘another Stanchina’, and that Leonardo, may have been the son of the late Michele, I am hypothesising this SOLELY based on the fact that Leonardo had a son named Michele.[107]

Given the fact we know Michele had ‘heirs’ when he passed away, we would expect to find at least two living children after 1522. With that in mind, I am also theorising that an Antonio Stanchina (who had numerous descendants through his son Gaspare) may also have been a son of Michele, but he would surely have still been a child at the time of the award of nobility. Again, I have no solid evidence other than the fact Michele’s father’s name was Antonio, and I would presume had named one of his sons after his father. We will come back to this Antonio when we visit the Stanchina branch that settled in Carciato.

I should stress that there are several other Stanchina males whose names appear in the early records for Malé, but owing to a lack of early marriage records in that parish, I have yet been able to identify their parentage.[108]

Overview of First Two Generations

Based on what we have observed so far, we can construct a rough chart of the male descendants of Terzolas ‘Founding Father’ Antonio Stanchina born the first two decades of the 1500s. I should point out, however, that while we know Michele had ‘heirs’, I am speculating that Leonardo and Antonio below were his sons. I have omitted my theory about a possible son of Guglielmo for now.

Click on image to see it larger.

Stanchina of Terzolas (1530 to early 1600s)

Working through the pergamene for Malé and the Thun of Castelfondo, we learn that Ser Nicolò who had been granted rural nobility in 1529 was already deceased by August 1546.[109] [110] From these documents, we find he had at least three sons – Matteo, Giovanni and Bartolomeo. However, of these, it seems Bartolomeo was the only son who had sons of his own: Cristoforo, Gregorio and Antonio.

Apparently, in his Will, Ser Nicolò had left a ‘perpetual legacy’, wherein every year 6 bushels of rye would be harvested and baked into bread, which would then be distributed to the people of the community of Terzolas. The legacy specified that this grain was to be harvested from a plot of land they owned in Terzolas called ‘in sum pra’ (‘pra’ is short for ‘prato’ which means a meadow or pastureland). Evidently, Ser Nicolò’s son Bartolomeo honoured his late father’s wishes and kept up this legacy throughout his long lifetime. But on 21 July 1580, around the time when Bartolomeo’s death seemed imminent (he was probably in his mid to late 70s), Bartolomeo’s son Cristoforo was named the administrator of his father’s assets – his ‘power of attorney’, so to speak – and appealed to the citizens of Terzolas to be released from this obligation. [111]

As a result of the meeting on 21 July, various exchanges were made, and the very next day (22 July 1580), we find Cristoforo Stanchina at Castel Caldes selling that very same plot of land to Count Sigismondo Thun. This time, the document says Bartolomeo was acting on behalf of his father, as well as his brothers Gregorio and Antonio.[112] The fact the Cristoforo is the designated legal representative infers he was the eldest of the three brothers, which, based on the birth dates of their children, does seem to have been the case.

The elderly Bartolomeo died sometime within the next two years or so, as we find another document drafted at Castel Caldes dated 14 October 1582 in which ‘Cristoforo and Gregorio, sons of the late Bartolomeo Stanchina of Terzolas’ are negotiating a solution to their debts to the Lords of Thun by giving them yet another plot of arable land in Terzolas, in a place called ‘in Lidrama’.[113]

Economic decline, but increasing numbers

It seems the Stanchina of Terzolas (or, at least this particular line) were experiencing at least a temporary economic decline, in contrast to their Livo cousins who seemed to be continually increasing in power, wealth and influence.

This does not mean they were in declining in numbers. Far from it, in fact. By the early decades of the 1600s, so many branches of Stanchina started to appear in Terzolas that we begin to see the use of soprannomi to distinguish one line from another. One of the granddaughters of the younger Rubinello Stanchina cites the name ‘Rubinel’ as a soprannome in her baptismal record on 6 August 1613.[114] The very next day, with find the birth of a Cristoforo Stanchina with the soprannome ‘Beatricis’, drawn from the name of his paternal grandmother, Beatrice.[115]

Overview of Descendants through Early 1600s

Below is a chart summarising the first four generations of male descendants of Ser Nicolò, son of Antonio, although it really is more of a descendant chart for Nicolò’s son Bartolomeo, as I have not identified any children for his son Matteo, and his son Giovanni seems to have had only daughters. The blue, green and peach colours show the descendant lines of Bartolomeo’s sons Cristoforo, Gregorio, and Antonio, respectively. To make the chart easier to read, I have omitted all female children, and all male children who died in infancy. I have also omitted all the wives, except for Beatrice, to show how the soprannome arose in the line descended from Bartolomeo’s son, Antonio:

Click on image to see it larger.

Similarly, this chart summarises the first four generations of male descendants Michele, son of Antonio. I have filtered the information the same way as I did in the chart above. However, I must point out that, although we know Michele had heirs, I am not yet fully confident Leonardo and Antonio were actually Michele’s sons. The blue line shows the descendants of Leonardo, and the green line shows the line for Antonio. The one person I am not completely certain I have in the correct place is Giovanni, son of Leonardo, as I have found no reference of his father’s name in any of the sources I consulted. I am theorising he is the son of Leonardo as he had a son of that name.

Click on image to see it larger.

Antonio’s line becomes relevant as we move to the next stage of our discussion, as one of his descendants became the found of the Carciato Stanchina in the early 18th century.

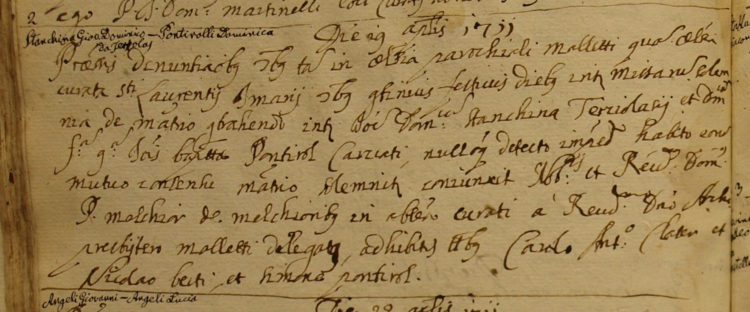

Stanchina of Carciato

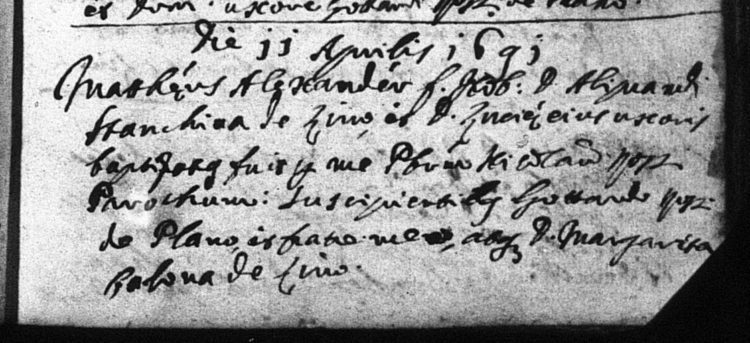

Among the notes by 19th-century priest historian don Pietro Silvestri in the parish archives of Terzolas, there is mention of a Giovanni Domenico Stanchina, said to have been a mason, who moved from Terzolas to Carciato (part of the parish and comune of Dimaro in southwest Val di Sole) after having married Domenica Pontirolli from that village on 19 April 1711. [116] [117] This couple thus became the ‘founding parents’ of the Stanchina in Carciato. Their marriage record, shown below, clearly states that Giovanni Domenico was from Terzolas, with no indication he was already living in Carciato, which infers he moved there only after his marriage.

Click on image to see it larger.

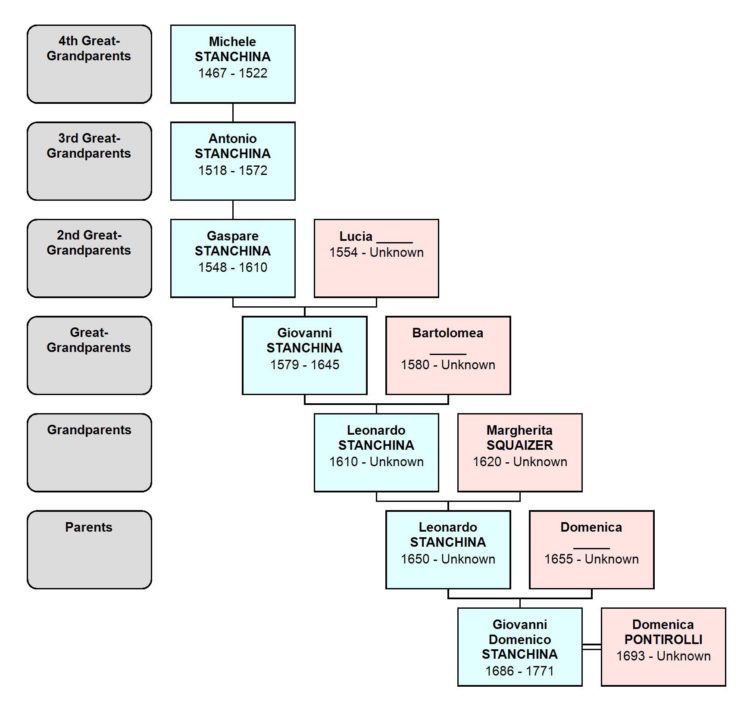

Ancestry of Giovanni Domenico, Founding father of Carciato Stanchina

The priest did not record the name of Giovanni Domenico’s father his 1711 marriage record, but this was not uncommon when a groom came from outside the parish, as the priest would not personally have known his family. However, there was only one Giovanni Domenico Stanchina born in Terzolas in the appropriate era. He was born on 10 December 1686[118], the son of Leonardo Stanchina and his wife Domenica (her surname is currently unknown, owing to a gap in the marriage record for Livo).

Below is a chart illustrating his paternal lineage back to Michele, son of Antonio, Founding Father of the Terzolas line. As mentioned at the end of the previous section, the one grey area for me is whether Giovanni Domenico’s 3X great-grandfather Antonio (ca. 1518-1572) was indeed the son of Michele, or of a different son of Antonio. But either way, we can see that the Carciato line has a direct link to the ancient Stanchina, as Giovanni Domenico was the 9th great-grandson of Belvesino of Tassullo from the early 1300s.

The Expansion of the Stanchina in Carciato

Historian Udalrico Fantelli tells us that the anagraph for the family of Giovanni Domenico and Domenica shows the couple had at least 12 sons and daughters in the parish records between the years 1712 and 1738.[119] I have not researched this family in detail, in my own research I have ‘met’ three of their sons – Giovanni Battista, Antonio and Pietro – all of whom had many descendants. Antonio and his wife Anna Domenica Mochen (married 16 Jul 1750)[120] are the 4X great-grandparents of one of my clients in the United States.

Fantelli tells us that, from this first nuclear family, the Stanchina expanded and spread out, until this family became one of the most solid and articulated ancestral lines of Carciato and, successively, in Dimaro.[121] That same author tells us that a Giovanni Domenico Stanchina, who, in his role as ‘regolano’, lead the important assembly of the citizens of Carciato that made the decision to build the new church in 1750.[122] Later, on 23 April 1764, we find a Giovanni Domenico Stanchina who was present as a witness at the drafting of an agreement in Mezzana.[123] I have yet to investigate whether these citing refer to the Giovanni Domenico who was head of the lineage or to one of his sons.

The Stanchina Today

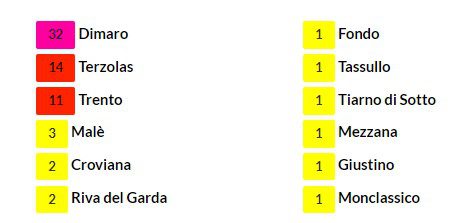

So many of the ancient families of Trentino have gone extinct over the centuries, the Stanchina continued to thrive in their three adopted villages (Livo, Terzolas, and Carciato) up through the early 20th century. A quick search on the Nati in Trentino website shows us that, between the years of 1815-1923, there were 634 children born with the surname Stanchina, and all but a handful of them were born in the three parishes we just discussed:

- 161 Stanchina children were born in the parish of LIVO.

- 255 Stanchina children were born in the parish of TERZOLAS.

- 201 Stanchina children were born in the parish of DIMARO (presumably from Carciato).

Of those from Livo, two were born in Preghena, a frazione of Livo. Twenty were recorded as ‘de Stanchina’ rather than ‘Stanchina’; these are all descendants of the noble Matteo Alessandro Stanchina. One child was baptised in the city of Trento, but as the family was from Livo (and were living there after that birth), I’ve included in in the Livo births.

This leaves only 17 additional Stanchina children born in scattered parts of the province over a period of more than a century. These usually appear with only one or two children showing up in each place, and do not appear to indicate any significant migration to these places prior to World War 1 and the years just after it.

Noticeably, the numbers in Livo are significantly lower than in the other two parishes. Perhaps that explains why, on the Cognomix website, no Stanchina families are listed for Livo at all, while there are still many families living in Dimaro and some in Terzolas/Malé.[124] Although I haven’t investigated this further, I feel we should not necessarily take this to mean they simply ‘died out’; rather, it is more likely they migrated elsewhere (including emigration to the Americas).

ABOVE: Chart from Cognomix website showing the number of Stanchina FAMILIES (not individuals) living in each comune.

Closing Thoughts

Before anything else, I would like to extend my sincere thanks to Robert Jusko for his patient proofreading of this article, and to Andrea Pojer for his deciphering a couple of strangely spelled place names I could not make out in some of the Latin documents. I do hope you found this article interesting, and that you feel I achieved my original goals, which was to show the origins of the Stanchina family, how they gained in power and influence, how they dispersed throughout the province, and how all the Stanchina of Trentino are ultimately related via a common ancestral patriarch. Speaking for myself, even though I do not have (to my knowledge) any Stanchina ancestors, I find their journey and the history of the times fascinating.

As some of you know, I have been working on a book entitled Guide to Trentino Surnames for Genealogists and Family Historians for some time now. That book, which currently has about 800 surnames (most in very rough form), is going to take me several more years to finish (plus I want to bring the total up to at least 1,000 surnames).

However, this week I decided to publish another book before the Guide is complete: a set of histories of selected Trentino families, which will be a composite of longer studies I have done on specific families, such as this article you have just read. That will still take me a couple of years to complete, but I already have a lot of material written for it. My aim will be to create a book of ‘case studies’ of origin and migration stories, which collectively can show us a bigger picture of the diversity of families who make up our beautiful ancestral province. I haven’t made up a working title for it yet, but I will surely let you know when I have.

In the meantime, if you enjoyed this article, or have comments or questions, I welcome you to share them in the comments field below. And, as always, if you wish to read more articles like this, I invite you to subscribe to this blog, using the form below.

This article is also available as a 31-page downloadable, printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, charts, maps, footnotes and resource list. Price: $3.25 USD.

CLICK HERE to buy this article in the ‘Digital Shop’, where you can also browse for other genealogy articles.

Until next time!

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

11 March 2022

P.S. I am currently taking client bookings for late May 2022 and beyond. If you would like to book a time to discuss having me do research for you, I invite you to read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, we can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://trentinogenealogy.com/my-tree/

NOTES

[1] The closest in sound is the surname Stancher, but it is not historically related (and probably not linguistically) to Stanchina.

[2] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 268.

[3] RAUZI, Gian Maria. Araldica Tridentina: stemmi e famiglie del Trentino. 1987. Trento: Grafiche Artigianelli, page 325.

[4] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino. Trento: Società Iniziative Editoriali (S.R.L.), page 337.

[5] GUELFI, Adriano Camaiani. 1964. Famiglie nobili del Trentino. Genova: Studio Araldico di Genova, page 117. Unlike the other references above, Guelfi does not specify Terzolas, but says merely ‘Val di Sole’.

[6] CICCOLINI, Tiziana; FANTELLI, Udalrico. 2013. Memorie di Terzolas. Cles: Centro Studi per la Val di Sole, page 181.

[7] ODORIZZI, Paolo. 2018. La Val Di Non e i Suoi Misteri – Volume I. On pages 461-484.

[8] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo, Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino, page 337. On this same page, he also offers the same linguistic origin for the surname ‘Stancher’ and its variants.

[9] LEONARDI, Enzo. 1985. Anaunia: Storia della Valle di Non. Trento: TEMI Editrice, page 385.

[10] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo, Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino, page 337.

[11] LEONARDI, Enzo. Anaunia: Storia della Valle di Non, page 385.

[12] GUELFI, Adriano Camaiani. Famiglie nobili del Trentino, page 117.

[13] AUSSERER, Carl. 1985. Le Famiglie Nobili Nelle Valli del Noce: Rapporti con i Vescovi e con i Principi Castelli, rocche e residenze nobili Organizzazione, privilegi, diritti; I Nobili rural. Translated by Giulia Anzilotti Mastrelli from the original German work Der Adel des Nonsberges, published in 1899. Malé: Centro Studi per la Val di Sole. Page 243.

[14] CICCOLINI, Tiziana; FANTELLI, Udalrico. Memorie di Terzolas, page 181. They reference a ‘Compravendita di diritto di decima’ dated 28 April 1423 in the Archives of the Thun family, Castelfondo line. This document is listed, but not fully transcribed, in the resource listed in the next footnote.

[15] VALENTI, Elena. 2006. Famiglia Thun, conti di Thun e Hohenstein, linea di Castelfondo. Regesti delle pergamene (1270-1691). Trento: Provincia autonoma di Trento. ‘Compravendita di diritto di decima’, 28 April 1423 (Cles), page 17, pergamena 14.

[16] STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 198.

[17] ODORIZZI, Paolo. 2018. La Val Di Non e i Suoi Misteri – Volume I, page 461-484. Also, via private correspondence, Odorizzi says this comes from Codice Clesiano, volume 2, page 210.

[18] This information was given to me directly by Paolo Odorizzi, who says he obtained this information from the APTn atti notaio Tomeo di Tuenno; but I have not seen the original document.

[19] ODORIZZI, Paolo. 2018. La Val Di Non e i Suoi Misteri – Volume I, page 461-484.

[20] CICCOLINI, Tiziana; FANTELLI, Udalrico, page 181.

[21] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1965 (reprint). Inventari e Regesti degli Archivi Parrocchiali della Val di Sole. Volume 3: La Pieve di Livo. Trento: Temi – Tipografia Editrice, page 301, pergamena 406.

[22] CICCOLINI, Tiziana; FANTELLI, Udalrico, page 181.

[23] CICCOLINI, Tiziana; FANTELLI, Udalrico. This as subsequent information about the sons of Nicolò appear on pages 181-182.

[24] STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 317.

[25] CICCOLINI, Tiziana; FANTELLI, Udalrico, page 181.

[26] VALENTI, Elena. 2006. Famiglia Thun, conti di Thun e Hohenstein, linea di Castelfondo. Regesti delle pergamene (1270-1691). Trento: Provincia autonoma di Trento, page 59, pergamena 111.

[27] VALENTI, Elena, page 60-61, pergamena 115.

[28] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. Inventari, Volume 3, La Pieve di Livo, page 301-303, pergamena 407.

[29] We know from other documents that Leonardo had at least two sons, namely Antonio and Nicolò.

[30] In this document, Bartolomeo refers to the other Stanchina as his ‘nephews’, but technically he was their first cousin. This same Bartolomeo is later found in Terzolas, where he is listed amongst the rural nobility in 1529.

[31] CICCOLINI, Tiziana; FANTELLI, Udalrico, page 182.

[32] STENICO, P. Remo, Notai, page 316-317. He is also cited in numerous documents in Ciccolini’s inventory for Livo.

[33] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. Inventari, Volume 3, La Pieve di Livo, page 159, pergamena 258. ‘Not. Nicolò Stanchina, son of the late ser Leonardo, son of the late ser Nicolò Stanchina di Livo’ signature in document dated 22 Jan 1553.

[34] CONTER, Luigi (don). 1982. Fatti Storici di Livo. Narrati ai suoi compatrioti da don Luigi Conter, parroco di Cloz. Trento: Stampalith. On page 67-68, he transcribes the Will, dated 18 April 1531, of a Melchiore Graziadei of Celledizzo, which was drafted by ‘Nicolò, son of Leonardo, son of Nicolò Stanchina of Livo, notary’.

[35] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. Inventari, Volume 3, La Pieve di Livo, page 145, pergamena 224.

[36] STENICO, P. Remo, Notai, page 302. Stenico says Giuseppe Sandris was active at least between the years 1519-1531. Guelfi and Stenico identify him as the author of the catalogue of rural nobility.

[37] GUELFI, Adriano Camaiani, page 160.

[38] CONTER, Luigi (don). Fatti Storici di Livo. On page 64, the author refers to a slightly different list, which he says was compiled by priest historian Giangrisostomo Tovazzi, in which ‘Ser Stanchina, notaio’ is further described as ‘de domo Aliprandina superveniente’, which means ‘from the following Aliprandini household’. This is surely an error (either by Conter or Tovazzi) and the words ‘de domo Aliprandina superveniente’ introduce the list of Aliprandini family members that follows, and have nothing to do with the Stanchina.

[39] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. Inventari, Volume 3, La Pieve di Livo, page 165, pergamena 276.

[40] This information is based on my own research, using the Livo parish records.

[41] Livo parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 28.

[42] Livo parish records, marriages, volume 1, page 6. As their last child was born in 1609, Maria had to have been very young (possibly about 16 years old) when they married in 1579. However, their first child was not born until January 1582, which may be an indication they did not consummate the marriage until she was closer to 18 years old. This was not an uncommon practice.

[43] STENICO, P. Remo, Notai, page 20-21. Stenico lists 24 Aliprandini notaries.

[44] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. Inventari, Volume 3, La Pieve di Livo, page 303, pergamena 408.

[45] Unfortunately, there is an 80-year gap in the Livo marriage records between 1650-1730, so we do not know all of these connections.

[46] Livo parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 64.

[47] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine, page 268.

[48] GUELFI, Adriano Camaiani, Famiglie nobili del Trentino, page 117. He says, however, that the predicate was ‘Leiffendorf, not Leiffenburg, a variant I have not seen in any other source.

[49] RAUZI, Gian Maria. Araldica Tridentina, page 325.

[50] Carl Ausserer (Le Famiglie Nobili Nelle Valli del Noce, page 243) incorrectly says this predicate was given to them in 1764, but he is surely confusing it with a later award where the predicate was embellished.

[51] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine, page 269. They say there was a red cross on the gold band, but the cross was actually added later, in 1764.

[52] RAUZI, Gian Maria. Araldica Tridentina, page 325.

[53] RAUZI, Gian Maria. Araldica Tridentina, page 325.

[54] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine, page 375.

[55] RAUZI, Gian Maria. Araldica Tridentina, page 325.

[56] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine, page 377.

[57] Livo parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 245-246.

[58] Matteo was alive when his son Bernardino married Marina Andreis on 28 Nov 1618 (Livo parish records, marriages, volume 1, no page number), but I do not know if he was still alive in 1624.

[59] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. Inventari, Volume 3, La Pieve di Livo, page 303-304, pergamena 409.

[60] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine, page 268. They refer to him simply as ‘Alessandro Stanchina’.

[61] GUELFI, Adriano Camaiani, Famiglie nobili del Trentino, page 117. He refers to him as ‘Mattia Alessandro’ Stanchina.

[62] My apologies: I did read this explanation in one of my sources, but at the moment, I cannot find the reference, so I am simply saying it ‘may’ be the case.

[63] Livo parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 174-175.

[64] This chart is from a tree I made using Family Tree Maker software, from information gathered during my research.

[65] Matteo Stanchina was born 5 September 1625. Livo parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 185-186.

[66] Livo parish records, marriages, volume 1, no page number.

[67] Agnese Tomasi was born 16 December 1616. Livo parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 117-118.

[68] ‘Agnese Stanchina’ died on 30 July 1664. Although it does not say ‘wife of Matteo Stanchina’, the only other Agnese Stanchina who was alive at this time was a young child, and the record is clearly for an adult.

[69] ‘Dominus Matteo Stanchina’ died on 30 March 1683. Livo parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number.

[70] CONTER, Luigi (don). Fatti Storici di Livo, page 94-95.

[71] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine, page 268.

[72] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine, page 268.

[73] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine, page 268. They refer to Aliprando Michele as ‘Aldobrando Michele’, but he was baptised Aliprando Michele in Trentino.

[74] Livo parish records, baptisms, volume 3, page 88-89. Many thanks to historian Andrea Pancheri for deciphering the word ‘Graecansi’ (of Graz), which I honestly could not make out in this document.

[75] TOVAZZI, P. Giangrisostomo. 1994. Varie Inscriptiones Tridentinae. Originally published in the late 1700s. 1994 version edited by P. Remo Stenico. Trento: Edizioni Biblioteca PP. Francescani, page 496, inscription 842. The exact words in Latin are ‘All’Illmo Signor Aldobrando Stanchina de Turri Pegnana zu Leiffendorff, Giudice Cesareo Regio e Preside del Civico Provincial Tribunale ec. in Trieste’.

[76] Using the parish records for Sarnonico, I have found five children for this couple, including three sons, but none is named Lorenzo. P. Remo Stenico (STENICO, P. Remo. 2000. Sacerdoti della Diocesi di Trento dalla sua Esistenza Fino all’Anno 2000, page 468) cites a Lorenzo Zini of Cavareno who died 16 May 1824 at the age of 76. This would mean he was born around 1748, which is when the couple’s eldest son Pietro Antonio Adamo Zini was born (2 February 1748). I can only assume that the letter was from this nephew, and that he adopted a different personal name when he took Holy Orders.

[77] TOVAZZI, P. Giangrisostomo. Varie Inscriptiones, page 496, inscription 842. The Latin exact words in Latin are ‘mortuus est dives, et sepultus est in inferno.’

[78] Caldes parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 329-330.

[79] Livo parish records, deaths, volume 2, page 62-63.

[80] CASETTI, Albino. 1981. Storia di Lavis. Giurisdizione di Königsberg-Montereale. Trento: Società di studi trentini di scienze storiche. Except accessed 6 March 2022 from ‘Castelo di Monreale (Königsberg)’ on the Piana Rotaliana website at https://www.pianarotaliana.it/territorio/luoghi-di-cultura/castelli/castello-di-monreale-koenigsberg

[81] This image, which I have cropped and enhanced, was downloaded from TIROLER LANDESMUSEEN. Tyrolean Coat of Arms; Fischnal coat of arms index. The writing on the card says the stemma is from 1764. Accessed 3 March 2022 from http://wappen.tiroler-landesmuseen.at/index34a.php?wappen_id=26296&drawer=&tr=1#next.

[82] GUELFI, Adriano Camaiani, Famiglie nobili del Trentino, page 153. He says the diploma is stored in volume 61, folio 270.

[83] LEONARDI, Enzo. 1985. Anaunia: Storia della Valle di Non. Trento: TEMI Editrice, page 446 (page number inferred).

[84] Livo parish records, marriages, volume 1, page 6.

[85] I don’t have the marriage record, but I have gleaned the information and estimated the marriage date from the birth records of their children.

[86] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine, page 74.

[87] Livo parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 300-301.

[88] Revò parish records, marriages, volume 2, page 117-118.

[89] Livo parish records, marriages, volume 1, no page number.

[90] Livo parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 137-138.

[91] Sarnonico parish records, marriages, volume 3, page 226-227.

[92] CICCOLINI, Tiziana; FANTELLI, Udalrico, page 182-183.

[93] CICCOLINI, Tiziana; FANTELLI, Udalrico, page 182. The authors reference Ausserer – Regesti di Castel Bragher, pergamena 593, dated 2 May 1478.

[94] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1939. Inventari e Regesti degli Archivi Parrocchiali della Val di Sole. Volume 2: La Pieve di Malé. Trento: Libreria Moderna Editrice A. Ardesi, page 138, pergamena 94. Bartolomeo, son of Antonio Stanchina of Terzolas is cited as a witness.

[95] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. Inventari, Volume 3, La Pieve di Livo, page 301-303, pergamena 407.

[96] CICCOLINI, Tiziana; FANTELLI, Udalrico, page 182.

[97] CICCOLINI, Tiziana; FANTELLI, Udalrico, page 182. On page 260, the cite a source from Ciccolini’s pergamene, but I have not been able to find the source they cite.

[98] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. Inventari, Volume 2, La Pieve di Malé, page 227, pergamena 269. The document, dated 14 October 1522, refers to ‘the heirs of the late Michele Stanchina’.

[99] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. Inventari, Volume 2, La Pieve di Malé, page 350, pergamena 354. The document, dated 7 October 1526, refers to ‘the heirs of the late Michele Stanchina’.

[100] GUELFI, Adriano Camaiani. Famiglie nobili del Trentino, page 161.

[101] CICCOLINI, Tiziana; FANTELLI, Udalrico, page 182.

[102] We know the younger Bartolomeo married Simona David, daughter of Giovanni David of Terzolas, as per the baptismal record of their son Giacomo, born 18 October 1559 (Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 48). We also know the couple were already married by 1 April 1558, as Simona is referred to as ‘the wife of Bartolomeo Stanchina’ when she is a godmother on that date (Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 33). This puts his most likely date of birth between 1530-1535, meaning he was most likely the eldest son of the elder Giacomo.

[103] Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 48. The baptismal record cites the names of both grandfathers, i.e., Giacomo Stanchina and Giovanni David.

[104] Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 139. The record cites the name of his paternal grandfather, Giacomo Stanchina.

[105] Leonardo (born 10 July 1560), Margherita (born 1 October 1562) and Domenica (born 5 June 1567), Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 53, 64, and 92, respectively.

[106] One anomaly is that the only son of this younger Rubinello was named Leonardo, which would normally make me suspect his father’s name was also Leonardo.

[107] Leonardo’s name is cited in the baptismal record of his granddaughter Maria Stanchina, born 31 October 1564, daughter of Michele Stanchina and his wife Flora. Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 78.

[108] There are a few Stanchina men, namely Antonio, Bernardo, Pietro and Simone, who were all most likely born between 1510-1525, whose parentage I have not yet been able to identify (although I suspect Antonio was a son of the late Michele). There are also a few other men in the next generation (born circa 1540-1552), whose fathers I have not yet identified.

[109] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. Inventari, Volume 2, La Pieve di Malé, page 353, pergamena 498. ‘Matteo, son of the late Nicolò Stanchina of Terzolas’ cited as a witness in a legal document dated 17 August 1546.

[110] VALENTI, Elena. Famiglia Thun (Castelfondo). Regesti delle pergamene, ‘Costituzione di censo’, 3 January 1551, Castel Caldes, page 151, pergamena 315. ‘Giovanni, son of the late Nicolò Stanchina of Terzolas…’

[111] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. Inventari, Volume 2, La Pieve di Malé, page 299-300, pergamena 465. The document also mentions another Bartolomeo, son of the late Giacomo Stanchina (Cristoforo’s 2nd cousin), as well as a Leonardo and a Nicolò Stanchina, but it does not identify their fathers.

[112] VALENTI, Elena. Famiglia Thun (Castelfondo). Regesti delle pergamene, page 204, pergamena 426.

[113] VALENTI, Elena. Famiglia Thun (Castelfondo). Regesti delle pergamene, page 212, pergamena 445.

[114] Maria, daughter of Leonardo ‘Rubinel’ Stanchina and his wife Agata, born 6 August 1613. Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 118. Leonardo was the son of the younger Rubinello.

[115] Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 119. Cristoforo (born 7 August 1613) was the son of Nicolò (born 19 September 1568), who was in turn the son of Antonio and Beatrice. Antonio was the son of the Bartolomeo

[116] CICCOLINI, Tiziana; FANTELLI, Udalrico. 2013. Memorie di Terzolas. Cles: Centro Studi per la Val di Sole, page 182-183.

[117] Dimaro parish records, marriages, volume 2(?), page 94-95.

[118] Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 3, page 244.

[119] FANTELLI, Udalrico. 1992. Carciato: il paese e la gente. Centro Studi per la Val di Sole, page 57.

[120] Dimaro parish records, marriages, volume 3(?), page 108. NOTE: The LDS church did not microfilm the records for Dimaro before 1770, but the Archivio Diocesano has made colour digital images of the early books that had been overlooked. Albino Casetti says there are 5 books of marriage records; I suspect this one is from volume 3, but I am unsure. The number of the digital file in Trento is P6150851.

[121] FANTELLI, Udalrico. Carciato, page 57.

[122] FANTELLI, Udalrico. Carciato, page 57.

[123] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1936. Inventari e Regesti degli Archivi Parrocchiali della Val di Sole. Volume 1: La Pieve di Ossana. Trento: Libreria Moderna Editrice A. Ardesi, page 182, C.n.575.