Genealogist Lynn Serafinn explains how and why to cite genealogy sources, and how good research habits can help you fill in the gaps when records do not exist.

Genealogist Lynn Serafinn explains how and why to cite genealogy sources, and how good research habits can help you fill in the gaps when records do not exist.

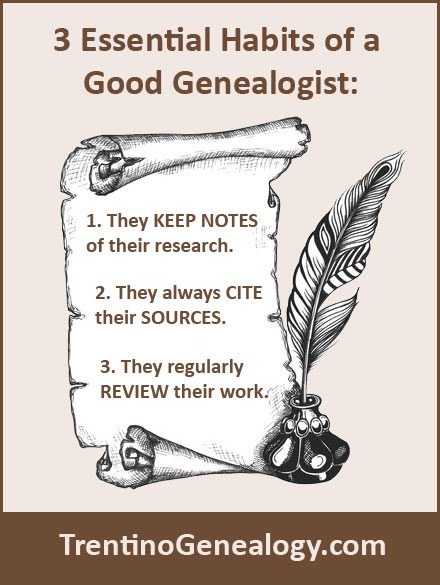

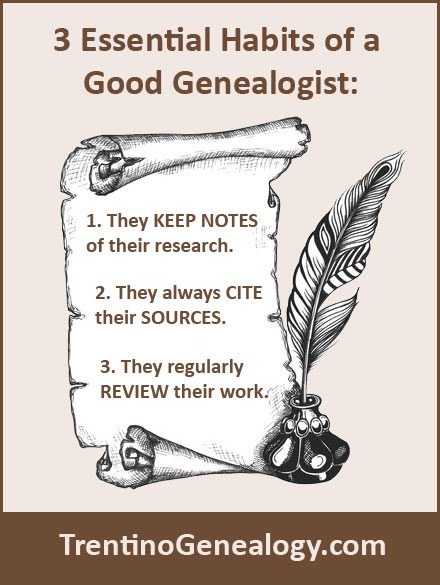

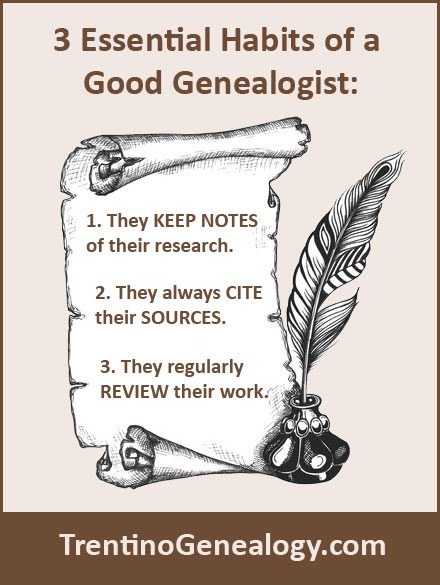

In my last article, I talked about the many ways we can make mistakes in genealogy and put the wrong information in our family tree. I also said the two most important habits of GOOD genealogists are:

- They always CITE their sources.

- They regularly REVIEW their work.

In writing today’s article, I realised I needed to add a third habit to the list:

- They KEEP NOTES of their research.

In fact, keeping good notes is so fundamental to research, I’m going to bump it up to #1 on the list of essential habits of a good genealogist:  Click on image to see it larger.

Click on image to see it larger.

Please SHARE this meme with your family history friends on social media.

Today, I want to talk about how these three habits work together in genealogy, and how they can help you create a trail of clues I like to call ‘genealogical breadcrumbs’, which can help lead you to the truth about your ancestors’ lives.

As always, while some elements of this article will be specific to Trentini genealogy, most of the concepts are equally applicable to ANY family history research, regardless of origin.

Keeping Notes of Your Research – Even When You’ve Found NOTHING

You might think ‘keeping notes’ means keeping track of what you discovered. However, I find it is just as important to keep a record of what I DID NOT find, and where/why I didn’t find it. For example, say you tried to find the marriage record of your great-great-grandparents in the parish records where your great-great-grandfather lived, but your search was unsuccessful. In such a case, you should write a NOTE in the description field for the marriage (Ancestry, Family Tree Maker, etc. will all have a description field) to the effect of:

‘I checked the marriage records for X parish between 1800 and 1820, but could not find it.’

I also find it useful to make a note of how thoroughly you’ve checked; after all, there is a big difference between doing a ‘quick check’ or scouring through the records three times. Make notes of ANYTHING of which you are uncertain, as well as any possible conflicts of information you might have found (e.g. two children for a couple appear to have been born too closely together).

What do you do if the original records for a parish/era no longer exist? Make a note saying something like:

‘There are no surviving marriage records for X parish between 1800 and 1820.’

Keeping such notes saves you time, as it helps ensure you don’t keep looking for the same records over and over (trust me, I’ve been there!).

What Are ‘Sources’?

A ‘source’ is a document (vital record, census, etc.), publication (book, website, blog article, etc.) or person (dictated verbally, in a letter, in an email, etc.) from which/whom you obtained your information. For example:

- If you find a birth date of your ancestor Giuseppe in an official birth certificate, the birth certificate is the source.

- If you find an estimated birth year for Giuseppe via a census record, the census record is the source.

- If your Aunt Matilda told you Giuseppe’s birth date, Aunt Matilda is the source.

- If you have obtained Giuseppe’s birth date from all three of the above, then ALL THREE are your sources – even if they give you conflicting information.

There are two types of sources:

- Primary sources are original documents of an event or person, such as a birth/baptismal record, marriage record, death record or military record.

- Secondary sources are quotes, opinions or other third-party accounts of an event or person, such as a book, article, letter or personal discussion.

In my opinion, certain records – such as census records – can be both primary and secondary sources. For example, it is a primary source for a person’s address on a specific date, but a secondary source of a person’s name or estimated year of birth (and they are often WRONG).

What Are ‘Source Citations’ and What Do You Put in Them?

A ‘source citation’ is a notation in your family tree of where you obtained your information. Most family tree programmes (Ancestry, Family Tree Maker, etc.) enable you to add and attach source citations to specific facts. A good source citation provides information about the source, such as the title, author, publisher, volume, year and page number of the source. If you are citing a parish record, for example, don’t just say ‘parish records’; rather, be sure to provide the name of the parish, the volume/book/part in which the record is located, and the page number (if there is one). It is also important to cite where/how the record was accessed, i.e. original record, digital image, microfilm, etc. Here’s an example of how I cite sources when working with digital images of the parish records at the Archives at the Archdiocese of Trento:

Santa Croce del Bleggio Parish Records (Santa Croce del Bleggio, Trento, Trentino-Alto Adige, Italy).

Repository: Archdiocese of Trento Archives

Trento file 4256260_00985; Santa Croce parish records, marriages, volume 1 (LDS film 1448051, part 5), no page number.

(After the citation, I typically transcribe/translate the document as well, but that’s a whole different topic.)

If that looks like a lot of writing, the first two lines are a template I set up in Family Tree Maker. I set one up for every parish I research. That way, I can pull down the template and insert the information about the specific reference, which you see on line 3. Even that is a ‘template’ I’ve made up, to enable me (or others) to locate the records where I obtained the information. In this case, ‘Trento file’ refers to the number of the digital image I obtained in Trento, and it really is only relevant to people who do research there, as these files are not available outside the archives.

The reference to the ‘LDS microfilm’ is so that people who might be doing research at their local Family History Centre can find the exact page where the record is located. Of course, the FHC are retiring their microfilm service at the end of August 2017, so this information will become less relevant as they move over to digital images in the next few years.

Even if your source is a word-of-mouth account, you can (and should) cite the person’s name, and possibly the year in which he/she provided the information. You might also wish to say whether they gave you the information from memory or if they had any documentation.

Don’t forget to cite YOURSELF as a source if providing information from first-hand knowledge, e.g. your own birth date, the birth dates of your immediate family members, etc.

There is no ‘set in stone’ method for citing sources, and yours don’t need to be as detailed as mine. But once you understand the reasons why it’s important to cite your genealogical sources (which we’ll look at next), you too might wish to be more thorough in your citations.

Why Are Source Citations Essential in Genealogy?

While citing sources might seem like the less exciting side of genealogy, most experienced genealogists will tell you that genealogy without proof, sources and/or documentation is simply MYTHOLOGY (just Google the words ‘genealogy sources and mythology’ and you’ll see how often this topic has been discussed). In ANY kind of research – but especially genealogy – source citations have a threefold purpose:

- CREDIBILITY. As I said in my earlier article, ‘The Science of Finding Your Female Ancestors from Trentino’, genealogy is all about formulating hypotheses and then finding evidence to support or dispute it. Without at least one reliable source, our ‘facts’ are meaningless. The more reliable sources you have to back up a claim, the more likely it is that our ‘facts’ are true. Generally, primary sources are considered more ‘reliable’ than secondary sources such as word-of-mouth, books or other people’s family trees (see my additional comments about this below*).

- ATTRIBUTION. There isn’t a researcher on the planet who hasn’t found information from someplace else. While sometimes that information is a primary source (like a parish record), other times it has come from someone else’s research. Regardless of whether you are using primary or secondary sources, you MUST give proper attribution. Otherwise, you are plagiarising someone else’s work and/or intellectual property. Proper attribution will also provide evidence of the reliability of the original source.

- CROSS-CHECKING. Genealogy is a continually unfolding process. In other words, you (and others) will continually unravel new mysteries, even after you have found evidence for a specific person. Sometimes, the information you have found for one person is crucial in helping solve the mystery of another. OR, sometimes the information you have put on the tree was entered incorrectly or was incomplete. Incorrect/incomplete information is especially common when you are just starting out and you don’t understand how to interpret the records properly. If you have carefully cited your sources, you can return to the original document, reassess it, and fix the incorrect or incomplete information. Citing your sources also enables OTHER researchers – either family members or people you may not even know yet – to cross-check and/or expand upon your information.

* SOMETHING IMPORTANT TO CONSIDER: Ancestry dot com gives you the ability to cite another person’s tree as a source. That’s all well and good, but if that person’s tree has no reliable (preferably primary) sources to back up their information, such a ‘source’ is no proof at all. I know it can be tempting to build your family tree as quickly as possible, but piecing together your ancestry using other people’s unsubstantiated information is likely to lead you WAY off track, and you will end up disappointed when you find out much of your family history is simply untrue.

Creating a Breadcrumb Trail – Recording and Citing ‘Implied’ Information

As suggested at the start of this article, good genealogical practice helps you create a trail of ‘genealogical breadcrumbs’, which can narrow down information, even when documentation for that information does not exist. When you work with original records or images of the same (such as microfilm or digital image libraries), you can find a great deal more information than you would in indexed records or (most) online databases. For example, priests often use the Italian word fu, or the Latin word quondam (often abbreviated as ‘q.’), to indicate someone is deceased. Typically, these designations will appear:

- IN MARRIAGE RECORDS: Before the name of a deceased father and/or grandfather of the bride or groom. In the latter part of the 19th century, you will also start to see it used to refer to a deceased mother of a bride/groom.

- IN BAPTISMAL RECORDS: Before the name of a deceased paternal grandfather.

- IN BAPTISMAL RECORDS: Before the name of a deceased father of an unmarried woman, or the deceased husband of a widowed woman, when she is the godmother of the child being baptised.

While such inferred information isn’t precise, it can help you create an estimated date of death for the person cited as deceased, as you know they died sometime before that event. Thus, you can enter an estimated date of death for that person, putting something like ‘Before March 1692’ in the date field on your tree. Less commonly, the word posthumous may appear before the name of the father in a baptismal record. This means the father died sometime between the date of conception and the birth of the child. This helps you narrow down the date of death to roughly a 9-month window. In this case, you can put something like ‘Between Jan – Aug 1709’ in your date field.

But here’s where good genealogical practice is especially important. When you estimate dates:

Be sure to cite the SOURCE(s) from which you INFERRED the estimate.

Why should you cite your sources when you’re just estimating a date? Two equally important reasons:

- Because you are likely to forget why you made that estimate in the first place. This could lead you to CHANGE the estimate to a date that is less precise or altogether incorrect.

- Because you may have made a mistake when you interpreted the record. Unless you know how to find your way back to the original record, you won’t be able to locate the source of the error. Without being able to check the original record, you might continue to conduct your research based on incorrect assumptions.

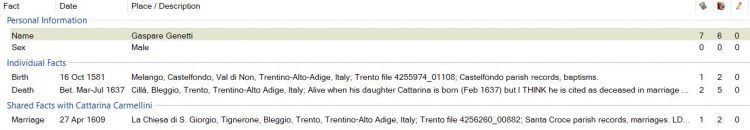

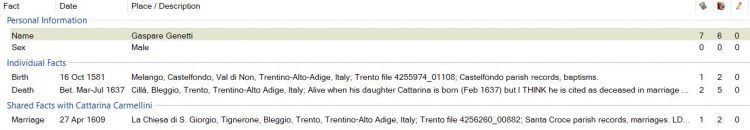

How do you cite a source when you are making an estimate? The SAME WAY you would cite your source for a baptism, marriage, etc. However, in this case, you would include NOTES about how you arrived at the estimate. For example, here is how I created a note for an ancestor of mine named Gaspare Genetti (later spelled Zanetti):

Click on image to see it larger.

The problem in finding the exact date of death for Gaspare is that, apart from a few death records for some of the parish priests, there are no death records for the parish of Bleggio before the mid-1660s. As I know Gaspare died before 1660, all I can do is formulate an estimate, based on available evidence. However, by carefully examining records of his family members, I managed to get a pretty good idea of when he died:

- In this case, I have estimated his death as, ‘Between March and July 1637.’

- Next, I explained how I deduced that estimate, saying that Gaspare was alive when his daughter Cattarina was born in February 1637, and that I ‘think’ he is cited as deceased in marriage record of his older daughter Margarita in July 1637. I say, ‘I think’ in this case, because I didn’t feel the handwriting on Margarita’s marriage record was 100% clear.

- I go on to say that I KNOW he was deceased by the time his other daughter Vittoria marries in 1657, as it is clearly written in that document.

- I then refer to five supporting source citations, which I linked to this estimated date. Each citation gives the Trento file, parish, page number, etc. as shown earlier.

- I also uploaded a couple of images for these sources, which helps the readers assess the evidence themselves. It also enables ME to go back and reread the documents, to see if I made any errors.

- Later, if I find other documents that give me an earlier or more precise date, I can change it, citing another source.

In this way – even if there are no existing records – it is often possible to formulate a narrow range of dates during which an event took place.

Creating estimates supported by source citations can also help speed up your searches through existing records. Let’s say you want to know the death date of your 5x great-grandfather, Giovanni. If you were to trawl through all the death records for his parish without having a rough idea of when he died, you’d probably end up searching aimlessly through hundreds of records, unsure whether ANY of them referred to your Giovanni. But if you have already formulated an estimate for his death, gleaned from information found in the marriage records of his children, or baptismal records of his grandchildren, you can limit the range of years in which you need to look. This will significantly decrease the amount of time you need to spend searching for a record, and increase the likelihood of finding the correct document.

The Importance of Reviewing Your Work

In genealogy, it is often all too tempting to go for quantity at the expense of quality. We want to go back one more generation, rather than dig more deeply, verify or refine the information already gathered. But I know from experience that, while it might seem like a dull proposition, going back to review your work can often breathe new life into your tree:

- A cryptic word on a record you looked at ten times in the past might suddenly leap out and you and make sense.

- Your language skills might have improved since the last time you studied a set of records.

- You may have become more skilled at deciphering messy handwriting.

- You might have recently discovered that your family used a soprannome during a certain period, which means you may have missed them in the records when you looked last time.

- You might look at your tree and suddenly realise two people are the SAME person.

- You might suddenly realise someone you thought was related only by marriage is actually the father of your 10x great-grandfather.

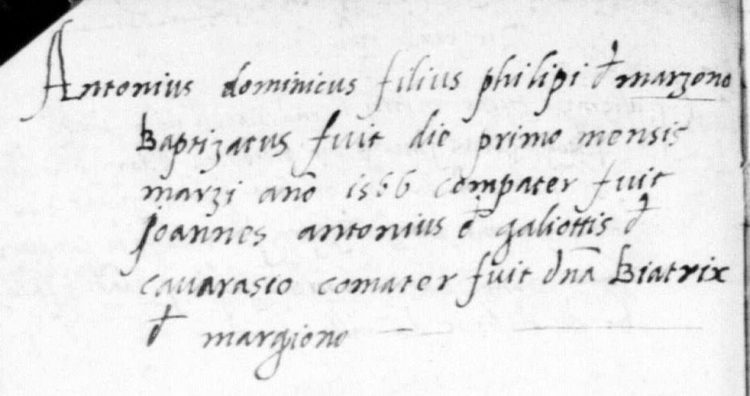

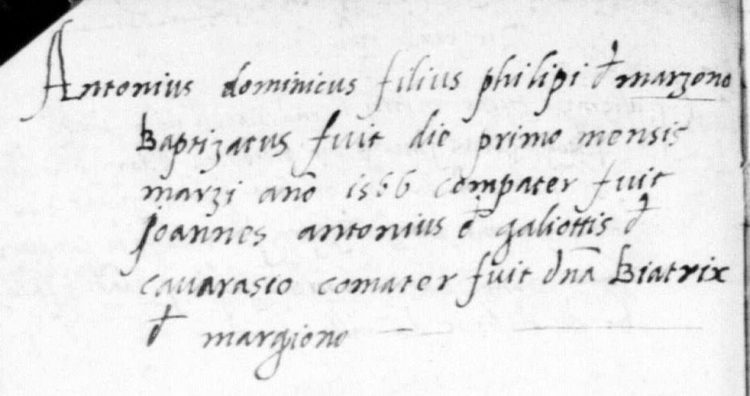

OR… You might realise an underlined word in a baptismal record is not the person’s surname (as it usually is), but their village. This happened to me JUST last night. I was reviewing some transcriptions made a few months ago, and noticed I had made a note that there was one record where I didn’t understand the surname. I took out the record and within a second I could see that the surname was missing from the record, and the priest had only given the first name and the frazione. Immediately, I realised I had found the 1566 baptismal record of one of my 9x great-grandfathers, Antonio Domenico Frieri (son of Filippo) of Marazzone. It seems so obvious to me now, but I must have looked at this record a dozen times before, without making the connection:

Click on image to see it larger.

There is no way ANY of us get it right – or complete – the first time around. Without regular review of our work, we may feel like we have hit a brick wall, while the information is staring us in the face and we simply haven’t yet noticed it.

Closing Thoughts

I hope you found this article useful and informative, and that it has inspired you to become a ‘master’ in our craft. Most of us who do genealogy are not only driven by a desire to find out about ourselves, but also by the wish to leave a valuable and lasting legacy for our children, grandchildren and extended family. To ensure that happens, we family historians must aspire to maintain the highest standards in every aspect of our research. As I said, while keeping notes, citing sources and reviewing one’s work might seem like the less ‘glamourous’ side of genealogy, they are the activities that will help your visions become reality.

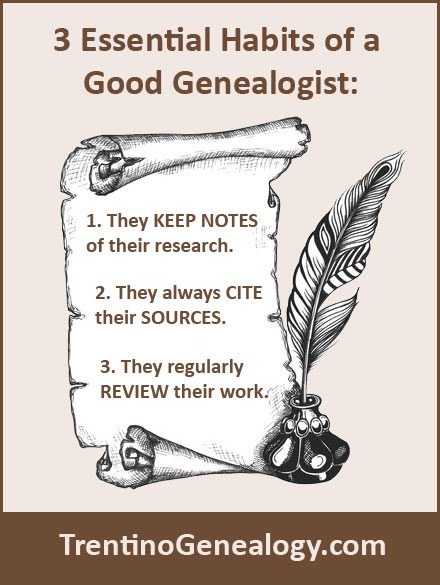

So, be sure to post this reminder over your desk:

Please SHARE this meme with your family history friends on social media.

I would welcome any comments or questions on this, or any other topic to do with Trentino Genealogy. Please feel free to express yourself by leaving a comment in the box below, or drop me a line using the contact form on this site.

Until next time, enjoy the journey.

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

P.S.: I am going back to Trento to do research on August 16th, 2017. If you would like me to try to look for something while I am there, please first read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. I look forward to hearing from you!

Subscribe to receive all upcoming articles from Trentino Genealogy!

Desktop viewers can subscribe using the form at the right side at the top of your screen.

If you are viewing on a mobile device and cannot see the form, you can subscribe by sending a blank email to trentinogenealogy@getresponse.net.

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

View My Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

LYNN SERAFINN is a bestselling author and genealogist specialising in the families of Trentino. She is also the author of the regularly featured column ‘Genealogy Corner’ for Filò Magazine: A Journal for Tyrolean Americans.

In addition to her work for clients, her personal research project is to transcribe all the parish records for the parish of Santa Croce del Bleggio (where her father was born) from the 1400s to the current era, as well as to connect as many living people as she can who were either born in Bleggio or whose ancestors came from there. She hopes this tree, which already contains tens of thousands of people, will serve as a visual and spiritual reminder of how we are all fundamentally connected.

View the Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

CLICK HERE to view a searchable database of Trentini SURNAMES.