Lynn Serafinn explains the importance and challenges of including death information in your family tree, and discusses 10 causes of death in 19th century.

Lynn Serafinn explains the importance and challenges of including death information in your family tree, and discusses 10 causes of death in 19th century.

When I was a child, my Trentino-born father frequently used to say,

‘Never forget, Lynn: our ancestors were survivors. You come from a long line of survivors. We ARE survivors.’

He said this so often, and with such conviction that, now in my 60s, I can still hear his voice and see his face as he is saying it. The idea of our family surviving against all odds was a powerful, driving force for him – one that was fundamental to his identity. He saw his heritage as a part of the choreography of the ‘natural order’ of life, where only those who are strongest will survive and thrive. Certainly, his worldview played a role in shaping my own way of seeing the world – and myself – as I grew up.

While, I admit, there is something seductively romantic about the idea that I have inherited the strength of my ‘survivor’ ancestors, my work in genealogy has caused me to reformulate my ideas on what exactly ‘survival’ means. We might imagine it means being able to withstand disease, overcome hardships, raise lots of children, and live to a ripe old age amongst our grandchildren or even great-grandchildren. But the reality of ‘survival’ of our Trentini ancestors often meant that they made it to adulthood at all. While it’s natural to imagine our great-great-great-grandparents as being wise, elderly people, the truth is, I am probably older right now than 95% of my ancestors were when they died. In fact, many of them died when they were younger than my 33-year-old daughter.

How does this information reshape the way we see our ancestors – and ourselves? Moreover, what else can death and dying tell us about who we are, as a people? Those are some of the questions I hope to address in this article, where we’ll be taking a short tour of DEATH as part of LIFE in Trentino in the past.

We’ll look at:

- The importance of including death information in your family tree, and how it brings depth to our understanding.

- The challenges of using death records for information, and how to glean information from other sources if death records are unavailable or incomplete.

- Some common causes of death in 19th century parish records, and translations of some of the Italian terminology you might encounter.

The Importance of ‘Killing Off’ Your Ancestors

A couple of years ago, I was reading a book called Tracing Your Ancestors Through Death Records by Celia Heritage (http://amzn.to/2hb1HJm), when a particularly memorable quote leapt out from the page:

‘If you are serious about your family history, then ‘killing off’ your ancestors is mandatory.’

When we research our personal genealogy, it can be all too tempting (if not ‘addictive’) to go for quantity over quality. We love the feeling of discovering one more person to add to our tree. Perhaps we’ve finally found the marriage record revealing the name of our great-great-great-grandmother, or we’ve unexpectedly come face-to-face with our 12x great-grandfather in a 16th century land agreement. It’s exciting – even emotionally stirring – when we make such wonderful discoveries.

But Celia Heritage’s point is this: while birth and marriage information is certainly fundamental to our genealogical research, until we know something about our ancestors’ deaths, we cannot get a truly accurate picture of their lives. If we really want to know where we come from, it is crucial for us to get into the practice of ‘killing off’ our ancestors, by discovering as much as possible about when, where and (hopefully) how they died.

Learning about our ancestors’ deaths can often tell us more about them than anything else. After all, when we are born, we are simply a name and a hope for the future. But when we die, our lives have already happened. All that we have done and experienced precedes us. We have left an imprint upon our families and communities, and they upon us. We have formed relationships, and we have left people behind who are affected by our lives – and by our deaths.

I would also add that it is just as important to research the deaths of ALL the members of your ancestors’ families, not merely those of your direct ancestors. Every death – even that of a new-born infant – has a physical, emotional and sometimes financial impact on a family. A single death can be the trigger that causes people to marry, remarry or even move locations. I doubt, for example, my Serafini ancestors would have moved from the parish of Ragoli to Bleggio in 1658, had not the older brother of my 6x great-grandmother Pasqua died, leaving her the only child to inherit.

The Challenges of Researching Death Information

Many of us from America and Britain are accustomed to looking for death information amongst the civil records. But in Trentino, civil registration only began in 1820. Prior to that, the primary record-keepers were Catholic priests in the local parish churches.

As mentioned in a previous article on this site, while the keeping of parish records was first mandated by Catholic Church at the Council of Trento in 1563, it took a while for it to become regular practice throughout the Church. Moreover, the practice of recording deaths tended to show up significantly later than the keeping of records of births and marriages. In my father’s home parish, for example, birth and marriage records begin in 1565, but death records begin more than 80 years later, in 1638. Some Trentino parishes did not start keeping death records until the middle of the 18th century.

Even when death records are available for a specific parish, the system for recording information is often erratic, until the middle of the 19th century, when it becomes more codified. While some records will tell you the age of people when they died, and some details about their familial lineage (e.g. ‘Giovanni Malacarne, son of Antonio of Sesto’ or ‘Marianna, born Gusmerotti, widow of Valentino Martini’), others will simply list the name and date of death.

Moreover, before it became standard practice to include the deceased date of birth in the record, the cited age at the time of death is often just an estimate. Priests often rounded the number up or down to the nearest decade. Alternatively, a member of the family of the deceased may simply have guessed their loved one’s age when the priest asked them. When such vagaries arise in the absence of any other information, you might be able to go back to the birth or marriage records and confirm you’re matching the right record to the right person. But sometimes, you’re not so lucky, and the scanty and conflicting information on the death record will simply leave you scratching your head.

Gleaning Death Information from Baptismal and Marriage Records

If death records are missing altogether for the ancestor or period you are researching, there are other ways you can at least narrow down the range of dates before/ after/ between which your ancestors died. The best way to do this is to look for clues in baptismal and marriage records.

When a child is born, his parents (especially the father) are typically cited in the baptismal record by referring to the child as ‘Giovanni, son of Paolo’, or ‘Cattarina, daughter of Giuseppe and Maria’ or something along those lines. Thus, in many records prior to the mid-19th century, we will see at least the paternal grandfather’s name in addition to the father’s (and, hopefully, the mother’s). As we progress towards the second half of the 19th century, we will start to see not only both grandfathers, but both grandmothers as well. The same is true for marriage records.

To find clues about a person’s death, we reading any parish record, look carefully and take note of any of these notations before any of the parents’ names, as they are all indications that a person (or persons) is deceased:

- qm or f.q.

- gm or f.g.

- fu

- furono

The first two are Latin abbreviations. The first is shorthand for ‘figlio (or figlia) quondam’, which means son (or daughter) of the ‘once’ so-and-so (e.g. ‘Antonio, son of the once Giovanni who is no longer with us’). The second is shorthand for ‘figlio/figlia gigantum’, meaning ‘son/daughter of the deceased’ so-and-so. Occasionally you will also see words like obit or defuntus, but these are less common in birth records.

The last two are Italian, and appear more commonly from the 19th century onwards. Fu is the third-person, singular, past tense of the verb essere, which means ‘to be’. Thus, fu means ‘he/she was’ (in other words, this person’s ‘being’ is now in the past). Furono is from the same verb, but in plural form; in other words, it indicates the record referring to more than one deceased person. For example:

- Giovanni di Antonio e fu Domenica, would mean Giovanni’s father Antonio was still alive, but his mother Domenica had passed away.

- Giovanni di fu Antonio e Domenica (or ‘vivente Domenica’), would mean his father was deceased, but his mother was still alive.

- Giovanni di furono Antonio e Domenica, would mean that both of Giovanni’s parents were deceased.

TIP: When reading baptismal and marriage records, don’t forget to check the godparents and witnesses, as these will also often have references to deceased fathers and husbands. If you look diligently enough, you will probably find some unexpected clues about an ancestor’s death date.

The Importance of Keeping Track of Estimated Deaths

I believe it’s important to keep a log of ANY clues you might discover for a person’s death, even if you don’t know precisely when it occurred. For example:

- If I am looking at a marriage dated 5 May 1742, and the husband is cited as ‘Giovanni di fu Antonio’, I will go to the death date for Antonio, and enter the words ‘Before 5 May 1742’.

- Then, in the description field or notes for his death (I use Family Tree Maker for this), I put something like: ‘Cited as deceased in the marriage record of his son Giovanni on 5 May 1742’.

- Finally, I cite the SOURCE of the record. For example: ‘Santa Croce parish records, marriages. LDS film 1448051, part 9, page 108’. As I get many of my digital images directly from the Archdiocese of Trento, I also enter the number of the file in the Trento system.

- Suppose, a few months later, I happen to stumble across a baptismal record dated 10 April 1737, where Antonio is cited as being the godfather of one of his neighbour’s children. This new information gives me a lower boundary for Antonio’s death (i.e., he had to have died after 10 April 1737). Now, I can go back to my record for him, and alter the estimated death date to ‘Between 10 April 1737 and 5 May 1742’, narrowing it to a 6-year window.

Keeping a careful log of all the clues you stumble upon in your research helps make finding death records easier later, and helps fill in the gaps if the original death records happen to be missing.

The Case of the Posthumous Father

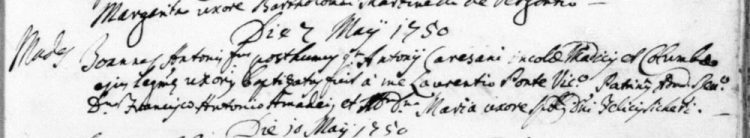

Sometimes, a man will have died shortly before the birth of one of his children. In this case, his name is often prefixed by the word ‘posthumous’ rather than fu in his child’s baptismal record. Here is the birth record (7 May 1750) for my 4x great-grandfather, Giovanni Antonio Caresani, whose father Antonio Felice is cited as ‘posthumous’:

(Click the image to see it larger)

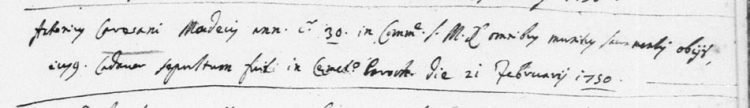

Knowing Antonio had to have died no more than 9 months prior to the birth of his son Giovanni Antonio, I could now narrow down his date of death to somewhere between September 1749 and May 1750. This enabled me locate his death record within a few minutes when I was in Trento. The actual date was 21 Feb 1750:

(Click the image to see it larger)

Note the death record says Antonio Caresani died at the age of 30. In this case, I already had Antonio’s birth information, but if I hadn’t, this information could have helped me locate his baptismal record. As I mentioned earlier, however, the given age on death records is OFTEN imprecise. In this case, the priest is off by three years, as Antonio was actually 33 years old, not 30, when he passed away.

Sadly, as is often the case with pre-19th century records, the record provides us with no cause of death. We can only wonder why a young man in the prime of his life died, leaving behind a young wife and at least two living children, who would later become my direct ancestors.

Infant Mortality and Early Childhood Deaths

In an earlier article on this blog I wrote about using the Nati in Trentino website for genealogical research. That site contains a searchable database of Trentini births/baptismal by the Catholic church between the years of 1815 and 1923.

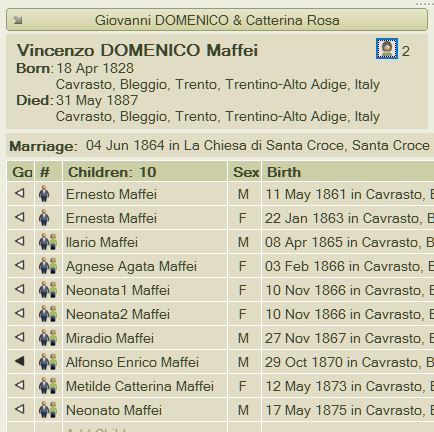

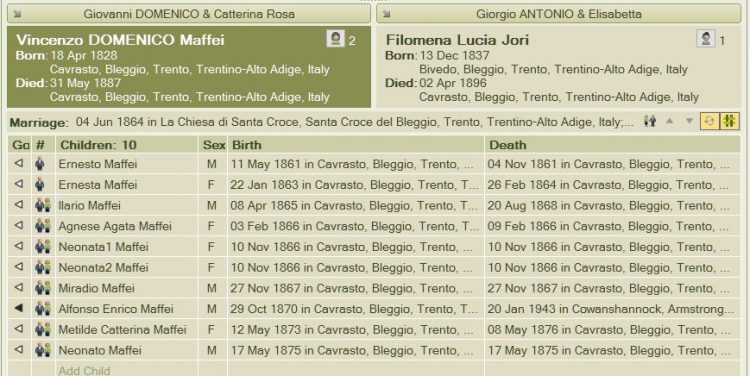

While it contains a wealth of information, Nati in Trentino has many significant limitations, as this next example will demonstrate. Here’s a snapshot of the birth dates as they appear on Nati in Trentino for the children of a man named Vincenzo Domenico Maffei, who goes by the name ‘Domenico’. For now, I only want to show you the left side of the screen (you’ll see why in a minute):

(Click the image to see it larger)

The first two children are via Domenico’s first wife, Angela, who died from tuberculosis in 1863, less than 3 months after the birth of her daughter, Ernesta. The other 8 children are via Domenico’s second wife, Filomena, whom you’ll meet in a minute.

Have a look at the twin girls Neonata1 and Neonata2 born in 1866, and the boy Neonato born in 1875. The terms neonato (for a boy) and neonata (for a girl) are NOT names; they simply mean ‘new-born’, and are used to indicate an unnamed, stillborn child, or one that died before it could be baptised (which was often on the same day). Another frequently appearing term in the parish records is innominato or innominata (‘unnamed male’ or ‘unnamed female’, respectively), which conveys the same meaning.

Based on Nati in Trentino’s information alone, we would be led to believe that three of Vincenzo’s 10 children died, and the other seven survived. But a direct examination of the baptismal records themselves will tell a different story altogether:

(Click the image to see it larger)

Have a look at the right-hand column underneath the word ‘death’. I obtained the death dates for ALL these children (except Alfonso’s) from their baptismal records. Many 19th century priests (at least in Santa Croce) would make notations about a persons’ death – and sometimes marriage – into that person’s baptismal record, even if it occurred years after the fact. Although death dates rarely appear in baptismal records before the 19th century, priests will often infer that a child died young, by putting a cross (+) next to the infant’s name in the record. While inconsistently used, you can find evidence of this practice even in very early records.

Shockingly, the notations in the baptismal records reveal that all but one of Domenico’s 10 children died under the age of 4. One little boy, Maradio born in 1867, managed to be baptised, but died later the same day. The only child to survive to adulthood is Alfonso, born 1870 – who ended up becoming the great-grandfather of one of my 9th cousins, who lives in the US.

The REAL story of this family is:

- Within a span of 14 years, Domenico saw the death of NINE children and a wife.

- Within the span of a decade Filomena gave birth to 8 children, only one of whom outlived her.

- Alfonso lost his father Domenico when he is 15 years old, leaving him to care for his widowed mother.

It simply boggles the mind, and changes our perspective of this family completely.

10 Causes of Death in 19th Century Italian Parish Records

Bearing in mind that it was not the standard practice to cite the cause of death until printed columns were introduced into the parish records around 1815, I’d like to round off this article by sharing some of the terminology you might see cited as ’cause of death’ in the mid-to-late 19th century.

I have two reasons for including this topic in this article:

- A few of my readers ASKED me to do it. 😉

- I believe seeing all these maladies lined up one after the other can really make the weight of our ancestors’ lives sink in. In fact, it kind of hits you like a brick.

It would be impossible to talk about all the possible causes of death in a single blog article. Really, it would take a book (and a LOT of research). So for now, I’m going to limit my discussion to 10 terms that might be more cryptic or less familiar to English speakers in the 21st century. The reason why they may be less familiar is partially because some of these diseases are not as common today as they were in the past, and partially because the terms themselves have changed over the past two centuries.

I’ve broken these 10 common causes into two categories: those that mostly affect infants and young children, and those that mostly affect adults, including the elderly.

I’ll warn you in advance, you may feel like crying.

Infants and Young Children

Tosse, pertosse, canine pertosse

These are all Italian terms for ‘pertussis’, more commonly known today as whooping cough. Whooping cough is a highly contagious, airborne, bacterial disease causing violent coughing fits, often leading to fatal complications. New-borns and babies under the age of one year are most at risk. Although doctors today use vaccines and antibiotics to prevent/treat the disease, it still claims the lives of many infants every year, even in ‘developed’ countries.

In one record, I also saw the term catarro soffocato. As ‘catarrh’ (catarro) refers to thick phlegm in the respiratory tract, this term means the baby suffocated on his/her own phlegm. My guess is that this might also indicate the child had whooping cough.

Grippe

This is the old Italian term for influenza or flu. The same term was used in English in the past, and the word grippe still means influenza in modern French. Historically, flu epidemics have claimed the lives of millions of people over the centuries, as the virus continually mutates as humans adapt to it. While adults often succumb to more virulent forms of influenza, babies and infants are often cited to have died from the more common winter strain of it throughout the 19th century.

For further reading, an interesting book on the so-called ‘Spanish Influenza’ of 1918 is Flu: The Story Of The Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus that Caused It by Gina Kolata (http://amzn.to/2haAUge). While not about Trentino, it gives terrific insight into the nature of epidemic diseases, and the challenges of protecting ourselves from them.

Disenteria

The literal translation is ‘dysentery’, which, technically, refers to an aggressive attack of parasites in the digestive track. Dysentery can cause high fever, diarrhoea and vomiting. In the case of infants (especially those still being breast-fed), I feel the term disenteria may more likely indicate they were suffering from chronic diarrhoea rather than actual parasites, eventually dying from dehydration.

Today, few of us think of diarrhoea as a lethal threat, but back then many babies and children died from it, all over the world.

Vermazione

Worms! I had never heard this term before working with the Trentini death records, but apparently, the term ‘vermination’ was also used in 19th century English medical texts. Vermination is any kind of worm infestation in the intestinal tract. In babies, vermination can also cause painful convulsions.

Believe it or not, I found a book from 1836 on Google Books with the somewhat catchy title of Medical commentaries on puerperal fever, vermination, and water in the head by a medical doctor named John Alexander. Dr. Alexander confesses that (at least at that time) doctors simply didn’t KNOW what causes babies to get worms.

Incompleto sviluppo

Literally ‘incomplete development’, this refers to a premature baby. Back then, if a baby was born prematurely, there was little hope for survival. We I first started working with death records, I was shocked to see how many infant deaths in the 19th century were actually due to premature births. My only guess for these high numbers is that perhaps a great many pregnancies failed to go full-term due to poor nutrition and lack of pre-natal care.

Adults and Elderly

Pellagra

Called the same in English, pellagra is an insidious lethal disease caused by a chronic deficiency of niacin (vitamin B6) in the diet. It is most commonly seen in populations where their diet consists mainly of corn (as in polenta), with few other sources of nutrition. This is because corn that has not been cured with lime can leech niacin from the body, unless there is ample supply of the nutrient from other food sources. During the 19th century, when many contadini in Trentino suffered economic hardship, diversity of diet was difficult. Although often fatal, pellagra is easily curable in all but the most advanced cases through dietary and nutritional changes. But unfortunately for many of our ancestors, niacin and its role in the disease was not discovered until the 1930s.

If you are interested in reading more about pellagra, I highly recommend the book A Plague Of Corn: A Social History Of Pellagra by Daphne Roe (http://amzn.to/2hk0HW9). Extremely well-written and insightful, she also includes one chapter where she talks about how the ‘polenta eaters’ in places like Trentino were impacted by this horrible disease.

Tisi, tisi polmonare; consunzione polmonare

These are all terms for pulmonary tuberculosis, commonly called ‘consumption’ in the 19th century. Tuberculosis was so endemic in Europe in the 19th century (and even to the early decades of the 20th century), that it forms the backdrop for many novels, plays and operas of those times. Attacking the lungs, it frequently struck down young adults in the prime of their lives. Some pages in the death records will have many tisi deaths, one after the other, all people in their 20s and 30s.

Tifo (tiffo)

Typhus, a bacterial disease often equated with wartime, it can be transmitted by lice, ticks, mites or fleas when people live in cramped quarters, and have insufficient hygienic facilities. Once it takes hold in a community, it can spread virulently. Thus, if you see one case of tifo, you’re bound to see many others within a short time span.

Apoplessia

The literal translation is ‘apoplexy’, an English which today refers to a stroke. However, in the past, the word apoplexy was used to refer to any kind of sudden death (often preceded by unconsciousness), including stroke, heart attack and aneurysms.

Marasma

Literally ‘decay’, this term was used to refer to dying of ‘old age’ rather than any specified disease or condition. You will only see it used with people of advanced age (usually 70 or older), and refers to the decline in bodily functions, muscle mass, bones, etc. Occasionally, you will see the term marasma senile, which is used where there is extreme wasting/weight-loss. Most of the sources I have read do not necessarily tie it to the word ‘senility’ or dementia, but it is possible these ailments would also fall under this ‘catch-all’ term.

Closing Thoughts

There is so much more we could discuss when it comes to talking about how our ancestors died. We could talk about ‘La Peste’ of 1630, which wiped entire villages off the map. We could talk about the world-wide cholera epidemic of 1855, which took its toll on Trentino. We could talk about the thousands of men and women who died between 1914 and 1918, during the First World War. Throughout history, the Trentini people have experienced it all – famines and floods, plagues and epidemics, war and economic hardships.

And while these things certainly took their toll on individuals and families, we – as a people – have survived. We identify with our culture; we recognise it as fundamental to who we are. Even those of us who are the children (or grandchildren) of those who emigrated to other lands, are still Trentini.

As my father said:

‘We are survivors.’

I hope this article has inspired you to become as curious about learning about your ancestors’ deaths, as you are about their births, marriages, and other life events. I also hope it has given you some useful tips and information to help you in your research. I would welcome any comments or questions on this, or any other topic to do with Trentino Genealogy. Please feel free to express yourself by leaving a comment in the box below, or drop me a line using the contact form on this site.

Until next time, enjoy the journey.

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

P.S.: I am going back to Trento to do research in January 2017. If you would like me to try to look for something while I am there, please first read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. I look forward to hearing from you!

Subscribe to receive all upcoming articles from Trentino Genealogy! Desktop viewers can subscribe using the form at the right side at the top of your screen. If you are viewing on a mobile device and cannot see the form, you can subscribe by sending a blank email to trentinogenealogy@getresponse.net.

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

View My Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

LYNN SERAFINN is a bestselling author and genealogist specialising in the families of Trentino. She is also the author of the regularly featured column ‘Genealogy Corner’ for Filò Magazine: A Journal for Tyrolean Americans.

In addition to her work for clients, her personal research project is to transcribe all the parish records for the parish of Santa Croce del Bleggio (where her father was born) from the 1400s to the current era, as well as to connect as many living people as she can who were either born in Bleggio or whose ancestors came from there. She hopes this tree, which already contains tens of thousands of people, will serve as a visual and spiritual reminder of how we are all fundamentally connected.

View the Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

CLICK HERE to view a searchable database of Trentini SURNAMES.