Genealogist Lynn Serafinn explains the role of the soprannome in Trentino and other parts of Italy and shows how to recognise them in genealogical records.

Sooner or later, anyone working with Italian genealogy will encounter something called a ‘soprannome’ (plural: soprannomi).

And if you’re working specifically on Trentino family history, you might also hear or read the word ‘scutum’, which is the Trentino dialect word for soprannome.

Despite the fact that EVERY family of Italian origin has a soprannome, many people researching their Trentino (or other Italian) ancestry either don’t know anything about them or fail to recognise them when they see them. And of those who DO know something about them, they often misunderstand the meaning and ‘behaviour’ of their family’s soprannome over time.

I’ve mentioned soprannomi within the context of other articles on this website but have never spoken about them in detail. As this subject is such an important part of Trentino genealogy, I thought it would be helpful to devote an entire article to the subject.

In this article, I will discuss:

- What soprannomi are and why they are used

- Why I think the word ‘nickname’ is not an appropriate term for them.

- The various ways soprannomi are recorded in parish registers

- How soprannomi are ‘born’, change, and what they might mean

- Why soprannomi can be both a blessing and a curse for genealogists

- How to record soprannomi in your family tree

Recording Data – The Computer as an Analogy

Think back to the days when you first started using a computer. Imagine you’ve just created your first Word document. You probably just saved it to the default ‘Documents’ folder without thinking about it. You might not even have given it a title, just calling it something like ‘Document 1.’

But over time, you made lots and lots of Word documents. Perhaps some were business letters. Perhaps others were letters to the family, stories you wrote or genealogy research notes. After a while, it became difficult to find the documents you had written in the past because they weren’t labelled clearly, and they were all in one big folder called ‘Documents’.

So, what did you do? Well, first of all, you probably started renaming the documents, so you knew what was what. But then, you might also have started creating folders inside the main ‘Documents’ folder. Perhaps one folder was called ‘Business Letters’, and another ‘My Research’, etc.

But soon, you created still MORE documents. For example, perhaps your research diversified, and now you wanted to separate your notes for different branches of the family. So, you started to create subfolders inside the folder called ‘My Research’.

By labelling your files clearly and creating a system of folders and subfolders, it became easier for you to identify and find the correct files when you needed them.

In simple terms, we can say that creating a structure is fundamental to being able to identify things and to distinguish one thing from another.

Name, Surname, Soprannome – An Increasing Need for Accuracy

If you think about it, names, surnames and soprannomi serve much the same purpose as the filing system on our computer:

- Our personal names are like the documents, in that each document is an individual entity.

- Our surnames are like the folders in which our documents are stored, in that they group many individuals into different categories.

- And, in the case of Trentino and other Italian ancestry, our soprannomi are like the subfolders within those folders, in that they create sub-groups within the group.

Just as your system for naming files was less complex when you started out using your computer, naming people was also less complex in the past, when the population was smaller, and most people were living in small, rural hamlets or homesteads.

Indeed, in the beginning, people were known mainly by their personal names along with their father’s name and/or their village of origin. Thus, in early records (and sometime even after surnames were already in use), you will see things like ‘Sebastiano of Sesto’, or ‘Nicolo’ son of Sebastiano of Sesto’.

But just like when you created folders because you had created so many documents you could no longer find what you were looking for, people started using surnames.

The Italian word for surname is ‘cognome’ (plural = cognomi):

Con = with

Nome = name

When the words are joined together, the ‘n’ in ‘con’ is changed to a ‘g’, which creates the sound ‘nya’ (like the ‘gn’ ‘lasagne’).

Thus, cognome means ‘with the name’, implying it is a kind of partner to the name.

While some surnames on the Italian peninsula appear in records as early as the 1200s or so, you don’t really see them becoming the norm until around the 1400s, and even then, they are often a bit ‘fluid’ and still in the state of change/clarification.

The ‘Black Death’ (1346-53) dealt a severe blow to the European population, wiping out an estimated 50% of the population. But gradually, and additional outbreaks of plague notwithstanding, the population not only restored itself, but eventually expanded by the 1600s.

Then, we see a situation where there was a limited number of cognomi within a small community, but lots of sons were being born, all naming their sons after their fathers. Just like your research documents, things started to get confusing. This is when soprannomi became necessary.

Like cognome, the word soprannome is also comprised of two Italian words:

‘Sopra’ = above or ‘on top of’

‘Nome’ = name

When the words are joined together, the ‘n’ is doubled.

Thus, together, the term means ‘on top of the name’.

What are Soprannomi and Why Are They Used?

As you might have already surmised:

A soprannome is an additional name used that is used to distinguish one branch of a family from others who share the same surname.

I think it is useful to think of a soprannome as a kind of ‘bolt on’ family surname, an idea that is also consistent with literal meaning of the word (‘on top of the name’).

Just as creating subfolders can be extremely helping in helping organise and identify individual files on our computer, soprannomi can be extremely useful in identifying the correct people – both during their own lifetimes, and in our family trees – especially when many people seem to have the same name and surname.

And, although I have NOT seen this mentioned in any of my research resources, I would assume that soprannomi might also have been considered useful (if not necessary) tools in helping ensure close bloodlines didn’t intermarry. As I mentioned in an earlier article (see link below), marriages between 3rd cousins or closer were only permitted via a special church dispensation.

Why I Think ‘Nickname’ is a Misleading Term

I have frequently seen the word soprannome translated into English as ‘nickname’. However, I believe this is a misleading term, and it doesn’t really reflect the true purpose and behaviour of a soprannome.

When we use the term ‘nickname’ in English, we usually mean:

- A shortening/adaptation of a person’s personal name (such as ‘Charly’ for ‘Charles’ or ‘Peggy’ for ‘Margaret’) OR

- An individual ‘pet name’ given to someone reflecting a personal trait or characteristic; alternatively, it may be associated with an achievement or event unique to them. Almost everyone will have had at least one ‘pet name’ in their lives, if not various ones from parents, schoolmates, spouse, friends, etc., according to their relationship with them.

While a soprannome might share some obvious similarities with one of these criteria, its historical origins might be so obscure that even the families who ‘inherited’ it may no longer know where it came from or what it means. Moreover, the original significance of the soprannome may have no relevance whatsoever to the family in the present day. This is quite different from what we associate with the term ‘nickname’, which is usually something intentionally given to someone to create a sense of intimacy and familiarity.

The function of a soprannome is also quite different from a nickname, as its purpose is to identify a specific lineage of people within a larger group, rather than one particular person. Perhaps the English word ‘clan’ might be a bit closer in meaning, but I don’t know enough about clans in other cultures to make a true comparison.

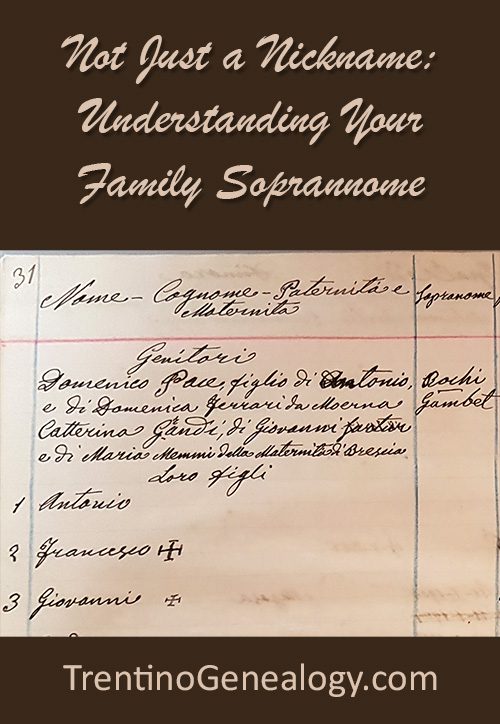

How Soprannomi Are Recorded in Parish Registers (or not!)

After analysing hundreds of thousands of Italian parish records from at least five different provinces, I can conclude:

There is NO consistently used system for recording soprannomi.

Soprannomi appear in all manner of ways in the records, depending on the era, the parish and the individual style of the priest. You can sometimes read decades worth of records in some parishes, and never stumble across a single soprannome. In fact, I have NEVER seen the soprannome for the branch of our Serafini family in any record, despite the fact it has most likely been around since the beginning of the 19th century. I only know the soprannome anecdotally, via my cousins in Trentino.

That said, there are some common practices for recording soprannomi, including:

‘Detto’ or ‘Dicti’

Perhaps the most commonly seen way of recording a soprannome is with the word ‘detto’ (if the record is in Italian, usually after 1800) or the word ‘dicti’ (if the record is in Latin, as is almost always the case before 1800). Without going into the grammar too much, these words are derived from the verb ‘to say’. You will often see them in documents with the meaning of ‘the aforesaid’, but in the context of surname/soprannome, they can loosely be translated as ‘called’ or ‘otherwise known as’.

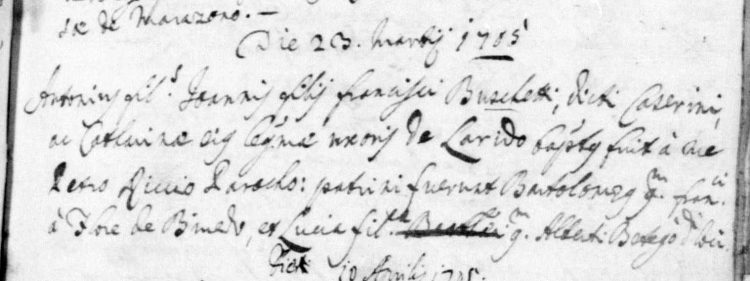

For example, consider this baptismal record from 1705:

Click on image to see it larger

Here we see the name of the baptised child is Antonio, and his father is referred to as ‘Giovanni, son of Francesco Buschetti, called (dicti) Caserini. In other words, the surname is Buschetti, and the soprannome for that branch of the family is Caserini.

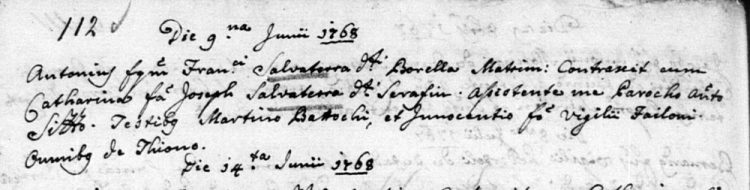

Be aware, however, that these words are FREQUENTLY abbreviated, e.g. ‘dto’ for detto, or ‘dti’ for dicti. Here’s one example from a 1768 marriage record from Tione di Trento:

Click on image to see it larger

Here, we see the groom is referred to as ‘Antonio son of the late Francesco Salvaterra called Borella’ (i.e. surname Salvaterra, soprannome Borella), and the bride is ‘Cattarina, daughter of Giuseppe Salvaterra called Serafin’ (i.e. the surname is again Salvaterra, and the soprannome is Serafin or Serafini). In both cases, the soprannome is indicated by the word dicti in its abbreviated from.

‘Vulgo’

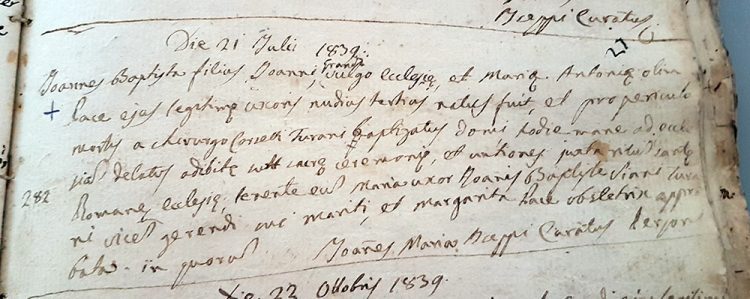

Recently when I did some research in Valvestino in the province of Brescia (Lombardia), I encountered another method of recording in soprannomi in Latin records, using the word ‘vulgo’. This word loosely means ‘commonly’, but in this context can be translated as ‘commonly known as’.

Consider this baptismal record from 1839 (during an era when I would have expected to see the record written in Italian):

Click on image to see it larger

Here, the child’s father is referred to as ‘Giovanni Grandi, vulgo Ecclesia’ (the priest had actually omitted the surname at first and inserted it above the line). Thus, the surname is Grandi, and the soprannome is ‘Ecclesia’. However, in this particular case, the family’s soprannome is actually Chiesa (which means ‘church’ in English), as the priest has used the Latin word for church (Ecclesia).

Surname Followed by Soprannome

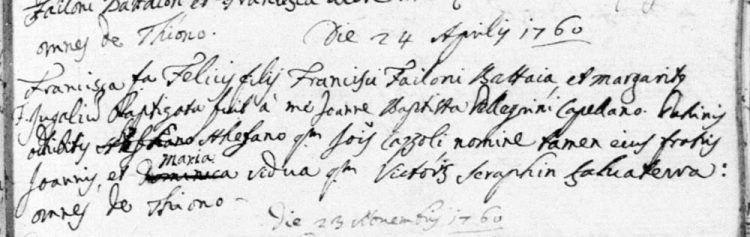

Some priests don’t bother to use an indicator such as detto, etc. for the soprannome, preferring simply to write the two names one after the other. Consider this baptismal record from 1760, again from the parish of Tione di Trento:

Click on image to see it larger

Here the priest refers to the father of the child as ‘Felice, son of Francesco Failoni Battaia’. It is understood from this context that the surname is Failoni, and the soprannome is Battaia – at least we HOPE that is what he means.

I say ‘hope’ because, in my experience, priests will occasionally REVERSE the surname and soprannome, making it difficult to know which is which. A perfect example is this same document, in the name of the godmother. She is described here as ‘Maria, widow of the late Vittorio Seraphin (Serafin or Serafini) Salvaterra’.

Having done a fair amount of research on the families of Tione, I am fairly certain the Vittorio’s surname was Salvaterra, and his soprannome was Serafin(i), not the other way around (in fact, we saw an example of this combination in a previous record in this article). I couldn’t say that this was definitely the case, however, without future research.

‘Equal’ sign

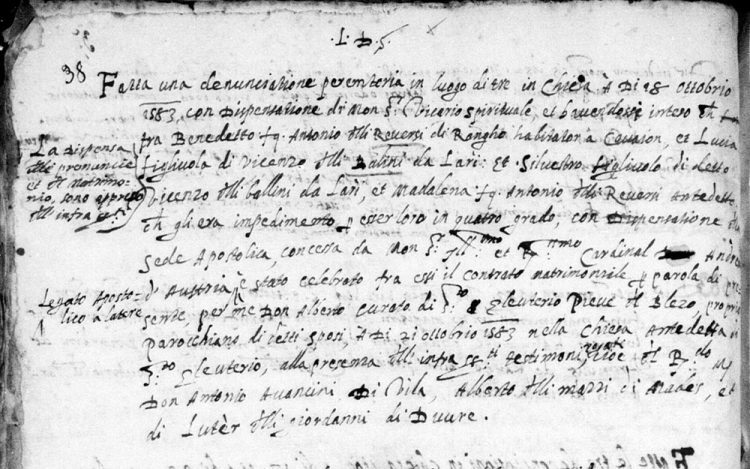

Sometimes soprannome is preceded by an ‘equal’ sign (=). I have seen this system used most frequently in 19th century records. Usually, this sign will be between the surname and the soprannome, but not always. Consider this 1838 death record from the parish of Cavedago in Val di Non:

Click on image to see it larger

Here, this 86-year-old deceased man is called ‘Tommaso Viola, son of the late Giovanni = Rodar’. In other words, his surname was Viola, and his soprannome was ‘Rodar’.

Article continues below…

Where Do Soprannomi Come From?

Much like Italian surnames, many (but not all) soprannomi may be derived from:

- The personal name of a patriarch or matriarch

- A place of origin of either a patriarch or matriarch

- An historic profession of the family

- A personal characteristic or attribute of a family or individual

Personal names

Some examples soprannomi I’ve encountered which mostly likely came from patriarchal personal names include: Stefani (from Stefano), Battianel (from Giovanni Battista), Vigiolot (from Vigilio), Gianon (from Giovanni), Tondon (probably from Antonio), and many others too numerous to count.

Sal Romano of the ‘Trentino Heritage’ blog told me that one of the soprannome for his Iob family was ‘Sicher’, which he theorises may have come from the personal name of a man named Sichero (Sicherius in Latin) in the 1670s.

Occasionally, you will see a soprannome that is derived from the name of a female ancestor, especially if the name is not so common. For example, one of my clients’ trees had the soprannome ‘Massenza’ because that was the name of one of the matriarchs for that line back in the 1700s.

Notice how I am expressing different levels of certainty here. That is because, of the above soprannomi, the only one for which I have definitely identified the origin is ‘Massenza’. The origins of the others are only hypothetical until research proves (or disproves) the theory.

Place of Origin

Some soprannomi indicate a connection with another place somewhere in the ancestral line. My friend and client Gene Pancheri, author of Pancheri: Our Story, told me that one of the Pancheri soprannomi is ‘Rumeri’, which means ‘a person from the village of Rumo’. He traced the origins of that soprannome to one of the female ancestors (who married a Pancheri of Romallo) who had come from Rumo.

Similarly, my own Serafini branch has the soprannome ‘Cenighi’ because my 4X great-grandmother, Margherita Giuliani (married to a Serafini in Santa Croce parish), came from the frazione of Ceniga in the parish of Drò (near Arco).

When making a tree for a client last year whose ancestors came from Tione di Trento, I noticed one of the soprannomi for the surname Salvaterra was ‘Ragol’. While I haven’t yet traced it back to its source, it is highly likely to have originated with female who came from the nearby village of Ragoli, which was often included within the parish of Tione in the past.

Notice how all of the examples above are linked to matriarchal lines. In my observation, most soprannomi that are linked to a place of origin tend to come from a female line. This is because women tended to move to the village/parish of their husbands (unless the woman was wealthy or had inherited property from her father).

There are exceptions, of course. On a list I recently received for Villa Banale in Val Giudicarie via Daniel Caliari at Giudicarie Storia, one of the soprannome for the surname Flaim was ‘Nonesi’, which means, ‘from Val di Non’. I found this interesting because Flaim is not indigenous to Villa Banale, and ALL the Flaim from that parish are descended from one man (named Bartolomeo Flaim) who came from Revò in Val di Non, who migrated there in the 1700s. Thus, all the Flaim there are technically ‘Nonesi’; it made me wonder how they figured out which branch got to ‘keep’ this soprannome as a memory of their origins.

Family Profession

Most soprannomi I have found that relate back to profession will refer to a ‘family’ profession rather than one for an individual. In this regard, the many variants on the word for ‘blacksmith’ spring to mind: Ferrari, Frerotti, Frieri, Fabro, Fabroferrari, etc. While most of these are also surnames in their own right, you will also see them crop up as soprannomi, telling you that, at least at some point in your family’s history, the blacksmithing was the family occupation.

Perhaps one of the most curious soprannomi I have ever encountered was when I was researching the Etro family of the Bassano del Grappa area of the province of Vicenza (Veneto), who migrated to the mountains of Madonna di Campiglio near Pinzolo in Trentino in the 1860s.

Their soprannome was ‘Rollo dei Mori’, which means ‘Rollo of the Moors’. In this era, the term ‘Moor’ referred to dark-skinned people from the Iberian Peninsula who were of north African descent, and usually Muslim.

It his book Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino, Aldo Bertoluzza stressed that the surnames/soprannomi derived from this word were most likely used to describe someone with black hair or very dark complexion, NOT someone who had Moorish background.

Bearing that in mind, there was something about the Etro family that MIGHT explain this curious soprannome: THEY WERE CHARCOAL MAKERS (carbonai).

Charcoal making was a ‘whole family’ operation, requiring the family to spend many months of the year in the woods, away from their main village. Children learned the skills of the profession from a young age, and sons often followed in their fathers’ footsteps, also becoming carbonai when they grew up.

In my mind, I imagine the family would often have been seen with blackened hands and faces as a result of their occupation. Perhaps ‘Rollo dei Mori’ was an affectionate or teasing term given to (or adopted by) the family because they were charcoal makers.

Of course, this is JUST my own theory.

SIDE NOTE: Interestingly, Moorish themes and motifs were very popular in Trentino, and indeed throughout Italy between the 17th and 19th centuries. Consider this amazing ‘Moorish’ chandelier in Castel Stenico in Val Giudicarie. I’ve seen many such artefacts in many places in the province. It also brings to mind the ‘Dance of the Moors’ in Verdi’s opera Aida.

Character or Attribute of Family or Individual

Recently I stumbled across the soprannome ‘Piccolo Vigiloti’, which suddenly cropped up after several generations of seeing ‘Vigilot’. This is an example of a patriarchal soprannome differentiating to reflect an attribute of either a branch of the family or an individual. We can safely assume that the ‘Vigiloti’ branch got too big for the soprannome to be useful, and rather than create a new soprannome, they called one of them ‘Piccolo’, meaning ‘small’. As this branch was not the main focus of my research at that time, I didn’t trace it back to its roots, but my guess would be it either means ‘the smaller branch of descendants of Vigilio’, or ‘the descendants of the YOUNGER Vigilio’ (which I think is more likely).

Another soprannome I encountered that might be connected to a personal attribute (although, again, I haven’t yet excluded other possibilities) is Papi, which I have seen in connection with the surname Rigotti in San Lorenzo in Banale in the 19th century. The word ‘papi’ is the plural of the word for ‘pope’ (papa), not to be confused with the word papà, which means ‘father’. Both Papa and Papi are surnames in other parts of the province, but the soprannome MIGHT have no connection with these. Rather, as Aldo Bertoluzza theorises in Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino, it might have been used as a nickname for a man (again, perhaps in an affectionate way) who was said to have the demeanour or ‘presence’ of a pope.

There are a lot of ‘mights’ here, of course, and I prefer NOT to speculate too much, lest it blind me to the truth later. I think soprannomi that are derived from attributes are often the most difficult to identify with confidence, as we have no way of knowing much, if anything, about the personality of the people or families in question.

Soprannomi Taken from the Surname of a Matriarch

I’ve put this topic under its own header because I didn’t want it to get lost amongst the other categories.

Some soprannomi are actually other SURNAMES. Some examples I’ve personally encountered include:

- Serafini/Serafin (a common surname in Ragoli and Santa Croce) was a soprannome for a branch of the Salvaterra in Tione in the 19th century (as we saw earlier).

- Armanini (a common surname in Premione) was a soprannome for a branch of the Scandolari in Tione in the 19th century.

- Conti (a surname in many parts of the province, but it also means ‘Counts’), was a soprannome for the Pancheri of Romallo in the 20th century.

- Bondi (a common surname in Saone, and later in Santa Croce) was is a soprannome for a branch of the Devilli of Cavrasto in the 1600-1700s.

- Bleggi (a common surname of Tignerone/Cilla’) was a soprannome for a branch of the Duchi in Sesto in the 1500-1600s.

Now, while I cannot say categorically this is true across the board, my ‘educated guess’ is that most of these surname-derived soprannomi are the surnames of a matriarch in the ancestral line.

In the case of the older lines, I probably will never be able to prove this theory, as the records won’t go back far enough to find the origins. Moreover, the further back you go in time, information about women in general becomes increasingly scant.

The fact that some soprannomi are identical to surnames can be a real bother – especially if a priest writes the soprannome before the surname in the record, as you have no way of knowing which is which without cross-referencing lots of other records.

Even worse is when a priest suddenly decides to use the soprannome INSTEAD of the surname, leaving the surname out altogether. That is definitely NOT fun.

When Soprannomi Become a Nightmare

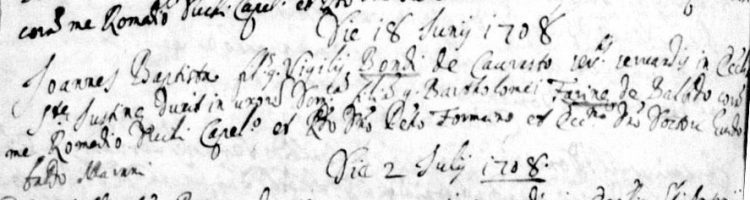

On that note, consider this 1708 marriage record, where the groom is clearly identified as Giovanni Battista, son of the late Vigilio Bondi:

Click on image to see it larger

As Giovanni Battista is also called Bondi in his 1690 baptismal record, I originally took this at face value, and assumed ‘Bondi’ was the family surname.

However, for the longest time I couldn’t figure out who this Bondi family were or how they connected to the rest of the tree. They just sort of ‘popped up’ out of nowhere, like time travellers.

Then, and only by a great stroke of fortune where the priest made a correction in the records, I saw another marriage record for the same Giovanni Battista (he had been widowed twice at this point), where the priest had ORIGINALLY written ‘Bondi’, and then crossed it out and wrote ‘Villi’ (one of many spelling variants for the surname ‘Devilli’) above it:

Click on image to see it larger

Only then did I realise that the ‘Bondi’ family and the ‘Devilli’ family were one and the same – which was really handy, as Giovanni Battista Devilli happened to be my 6X great-grandfather.

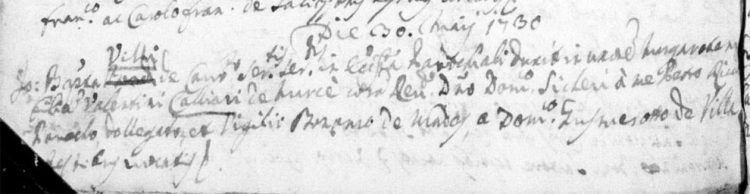

Now consider this record of a double marriage in 1583, in which two siblings married two other siblings:

Click on image to see it larger

Now, I know many of you will find this challenging to read, so let me just identify the key people:

- Benedetto REVERSI (son of the late Antonio) married Lucia BALLINA (daughter of Vincenzo)

- Silvestro BALLINA (son of Vincenzo, hence brother of Lucia) married and Maddalena REVERSI (daughter of the late Antonio, hence sister of Benedetto)

In this record, the priest (don Alberto Farina) has apparently recorded the surnames for the couples, without and mention of soprannome.

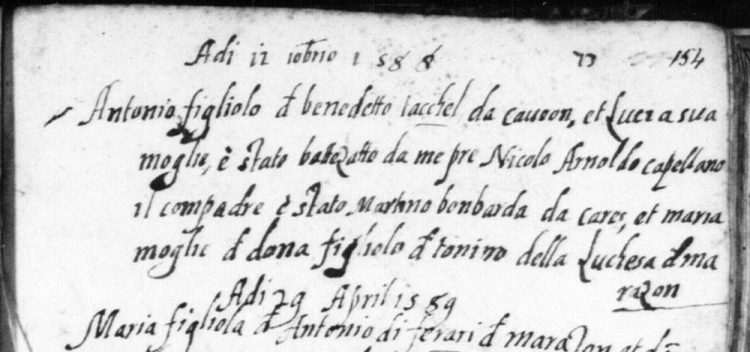

But now have a look at this baptismal record from 1588, written by a different priest (Nicolo’ Arnoldo) of the same parish:

Click on image to see it larger

The child’s first name is Antonio, and his surname (or so we assume) is underlined in the first sentence. It looks like ‘Tacchel’, but I have also seen it spelled ‘Tachelli’ in other records. I also found a record for Antonio’s elder sister, ‘Margherita Tacchel’, born in 1568.

Like the ‘Bondi’ family, this ‘Tacchel/Tachelli’ family were kind of floating in space on my tree for the longest time because I just couldn’t figure out who they were. But the answer was staring me right in the face (you can probably already guess it, as I’ve already shown you the document with the answer).

As you can see in Antonio’s baptismal record, his parents’ names are ‘Benedetto’ and Lucia’, and they lived in Cavaione. Now, remember we are talking about tiny hamlets, especially back in 1588. Only a handful of extended families would have been living in each frazione.

Add to that, the name ‘Benedetto’ is not a super common. But the combination of Benedetto AND Lucia in Cavaione in the 1580s? What are the chances of there being more than one such couple?

The answer is: none. There was indeed only one couple with those names in that village at that time.

As my tree is pretty large, I ran a few filters in my Family Tree Maker programme to find a ‘Benedetto’ living in Cavaione in this era and found Benedetto Reversi and Lucia Ballina, whose marriage I had already entered into the tree. What’s more, I knew that Benedetto’s father’s name was Antonio, and it was the usual practice back then to name the first son after the paternal grandfather.

All this made a very strong case for concluding that these were one and the same couple, and that ‘Tachel/Tachelli’ was a soprannome for this branch of the Reversi family (a surname that is still in use to this day in that parish).

MAIN ‘TAKEWAY’: If you see a surname that just sort of ‘appears’ in the records, and no mention is made that the family came from someplace else, consider the possibility that you are looking at a soprannome and that this family may already exist in your tree.

SIDE NOTE: The surname for the ‘Ballina’ family here eventually become ‘Fusari’. But I digress…

Article continues below…

The Ever-Changing Nature of Soprannomi

While the linguistic conventions for creating soprannomi might be similar to those for surnames, there is one BIG difference between them:

While surnames tend to stay the more or less the same for a long time (often for centuries), soprannomi will CHANGE whenever they need to, sometimes from one generation to the next.

Whenever a branch of a family gets very large, with lots of male descendants carrying the family surname, new soprannomi will suddenly spring up to differentiate these various male lines. This is why you might sometimes see a father with one soprannome, and his son with another.

So, if a relative tells you that your family’s soprannome is such-and-such, don’t just accept it something ‘cast in stone’. It might be so, but then again it might not. It’s essential to know WHEN they are talking about. If that person saw that soprannome in a book or in some parish records from the 1600s …well… it is highly unlikely this will be your family soprannome TODAY. Many soprannomi will be used only three or four generations (sometimes less) before they morph into something else.

Remember, it’s just like creating subfolders (and sub-subfolders) on your computer. There is no way to keep everything straight without continual, dynamic change to adapt to new situations and needs.

And sometimes, but less frequently, these adaptations may result in a more radical change, where a soprannome will replace the surname altogether. In my father’s parish of Santa Croce, for example, the family now known as ‘Martinelli’ used to be called ‘Giumenta’ before the 1630s, adopting their soprannome (apparently derived from a patriarch named Martino who was born around 1515) as their surname. Similarly, the present-day surname ‘Tosi’ in the same parish came from the soprannome of a branch of the noble Crosina family of Balbido.

Unless you are aware of these shifts from soprannome to surname, it can seem like your ancestral family has vanished into dust when you are trying to trace them backwards.

Tracing the Origins of Your Family’s Soprannomi

As you can see, origins and behaviour of soprannomi are highly varied, often unclear, and constantly changing. As such, tracing the origin and meaning of a soprannome can range from really obvious to doggedly elusive.

But if we are to have even the slightest chance of understanding them, and to using them as genealogical tools, we must make it a practice to keep a record our family soprannomi whenever we encounter them. They are not just colourful names, but important clues as to our ancestral lines, which can help us identify specific people, places and/or occupations of the past.

If you haven’t done so already, I highly recommend that you start keeping a list of soprannomi, taking care to record:

- The SURNAMES they are connected to

- The VILLAGES in which they appear

- The DATES (both the earliest AND the most recent) you have seen them in a record

I keep an ongoing list of soprannomi for my father’s parish, mostly from the 1500-1700s. I keep it as a ‘general task’ in my Family Tree Maker programme, and refer to it frequently. For me, those years are the most crucial to record, because (as already illustrated) there are so many instances of the priests using soprannomi instead of surnames. Without this ‘road map’ I could easily get lost.

Recording Soprannomi in Your Family Tree

I believe it is important to record soprannomi in your family tree, not only because they are an important part of your family history, but also because doing so will also help you keep track of your ancestral lines.

So, what is the ‘best’ way of doing this? I think it ultimately comes down to personal choice. I’ve used a variety of methods in different trees,all with their own advantages/disadvantages. Below are a few options you might consider.

TIP: Whichever method you choose, BE CONSISTENT. Try to use the same method throughout the same tree. My oldest tree (now around 26,000 people) has a patchwork of styles, which I am gradually trying to standardise.

OPTION 1: Soprannome as a MIDDLE NAME

Sometimes I put soprannomi in ALL CAPS as a middle name just before the surname.

This has the advantage of making things visible for me to find them quickly in the index when using a programme like Family Tree Maker or searching for that person on Ancestry.

However, it can also be confusing, as I also use the same method with middle names that are used as the primary name by which the person was known.

OPTION 2: Using ‘Also Known As’

Both Ancestry and Family Tree Maker have an option for ‘also known as’ (AKA).

This might seem like a good choice for a soprannome, but I feel that is better used for when someone is known by one of their middle names OR an actual NICKNAME as we think of it in English.

OPTION 3: The ‘Double-Barrelled’ Surname-Soprannome

In some parishes, the surnames are SO repetitive, and the priests CONSISTENTLY used soprannomi in just about every record, I have occasionally opted to HYPHENATED the surname with the soprannome. This was a method I used when making a tree for someone with family from the parish of Tione di Trento, as the soprannome in that parish are almost always see in conjunction with the surname.

The advantage of this method is it immediately organised everyone with the same surname-soprannome combination alphabetically in the person index for the tree, which is actually very useful.

The disadvantage is that, if you don’t know a person’s soprannome because it wasn’t recorded in the record, they might look like they are disconnected from their branch of the family.

OPTION 4: Create a Custom Fact or Event Called ‘Soprannome’

Although sites like Ancestry and programmes like Family Tree Maker don’t have a ‘soprannome’ in their default settings, it is possible to create a ‘custom fact’ (in Family Tree Maker) or ‘custom event’ (in Ancestry) and label it ‘soprannome’.

Personally, I believe this the BEST option, as it makes it absolutely CLEAR that this name is a soprannome and not something else. When using Family Tree Maker, it gives you the additional advantage of being able to create filtered lists or custom reports for specific soprannomi (which can be really informative). Equally important, you can also write NOTES about the soprannome ‘fact/event’, where you can discuss how it was derived, when it started, where it was recorded, or any other relevant information.

UNBREAKABLE RULE: Record WHERE You Found It

Regardless of which method you choose or devise to record your family’s soprannomi, there is one ‘unbreakable rule’ I strongly advise you include in your research practice:

After the soprannome, make a note of where you found it – preferably the earliest record.

For example, if a soprannome is in Giovanni’s baptismal record, put down ‘as per Giovanni’s baptismal record’ or something to that effect.

But what if it’s NOT in the baptismal record for Giovanni, but in the baptismal records of two of his children? Then, write ‘as per the baptismal records of his children, Antonio and Maria,’ etc. This helps you remember that the soprannome MIGHT have started with that generation, and not earlier. Later, if you find an earlier record, change the notation to reflect that.

Please trust me on this point. In the past, I neglected this important ‘rule’, which resulted in me not being able to identify where the soprannome first entered the tree, which can potentially create some confusion as you move backwards in time.

How NOT to Record Soprannomi (or Nicknames) in Your Tree

Two things you should NEVER (ever!) use in the name field for people in your tree are:

- Quotation marks (AKA inverted commas)

- Parentheses (AKA brackets)

I’ve seen these on so many trees on Ancestry, I’ve lost count. They are especially common in trees where people changed their names after immigration.

SIDE NOTE: While not on the subject of soprannomi, I really want to stress that married surnames should NEVER be part of a woman’s name – neither in the name field, and not in the ‘also known as. It is already understood that she would possibly have been known by her husband’s surname if she lived in the US or UK. Besides, when we are talking about Italian women, many, if not most, retain their maiden names throughout life.

So, let’s have a look at what a MESS all these variables can create. I’ll use my father’s eldest sister as an example (both she and my dad are deceased):

- My dad’s sister was born Pierina Luigina Serafini,

- She was known as Jean Serafinn in America.

- She was sometimes called ‘Gina’ in the family and ‘Jeannie’ by American friends.

- She was married to a man whose surname was Graiff who died young.

- Later she remarried a man with the surname Watson (he is also deceased).

- Oh, and just for the heck of it, let’s go ahead and throw in our family soprannome, ‘Cenighi’.

Using the ‘quotation mark’ and ‘parentheses’ methods, and inserting her married surnames, my poor aunt’s name might end up looking like this:

Pierina Luigia “Gina” (Jean Serafinn) “Jeannie” Serafini “Cenighi” Graiff Watson

Please DON’T do this!!

Not only is this only horribly confusing to as to what her name actually IS, but all those quotation marks and brackets can cause errors in software programmes.

The best policy is to record the person’s name AT BIRTH in the name field, and then put alternative names in the ‘also known as’ field. And, as mentioned, the husbands’ surnames stay with the husbands, not the wife.

Thus, here is how my aunt SHOULD be entered into the tree:

- NAME: Pierina Luigina Serafini

- ALSO KNOWN AS: Jean Serafinn

- SOPRANNOME: Cenighi (not in records, but via verbal info from Serafini cousins)

- HUSBAND 1: Albino Graiff

- HUSBAND 2: Gary Watson

If you really wanted, you could put additional ‘also known as’ to put her nicknames ‘Gina’ and ‘Jeannie’, but I think those are unnecessary, as we already know she was known as ‘Jean’.

Also, if you wanted (and if you knew enough information), you could write some notes about the historical origins of the soprannome in the notes for that fact in Family Tree Marker…. something I am again only just starting to integrate into my own trees. Here are some notes I’ve entered about the Cenighi soprannome:

The soprannome ‘Cenighi’ originates with Margherita Giuliani, who married Alberto Serafini in 1803, as she came from the frazione of Ceniga in the parish of Drò (near Arco). Their descendants are thus known as the ‘Cenighi Serafini’. I have not yet seen this soprannome in any records; rather, I was told the soprannome by Luigina Serafini (daughter of Luigi Paolo Serafini and Gemma Gasperini). Apparently, the family were unaware of the origin of the soprannome prior to my researching the family history.

Closing Thoughts

Thanks so much for taking time to read this article on soprannomi. I do hope you enjoyed it, and found it informative and useful to your research. It’s an article I’ve been wanting to write for some time now. It’s a complex topic – in many ways more complex that surnames.

I also hope I have presented a convincing argument AGAINST the word ‘nickname’ as a translation for the word soprannome. It really doesn’t do the term justice, nor does it reflect its important social function. Perhaps we can all agree to stick to using the original word – soprannome.

I would mean so much to me (and you would really help me know if these articles are explaining things clearly enough), if you could take a moment to leave a few comments below, sharing what you found most helpful or interesting about the article, or asking whatever questions I may not have answered.

Until next time!

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

6 Oct 2019

P.S. My next trip to Trento is coming up in November 2019. My client roster for that trip is already full, but if you would like to book a time to discuss having me do research for you on a future trip in 2020, I invite you to read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, we can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

P.P.S.: As I’ve had so many other projects lately, I have still not finished the edits for the PDF eBook on DNA tests, which I will be offering for FREE to my blog subscribers. I will send you a link to download it when it is done. Please be patient, as it will take a month or so to edit the articles and put them into the eBook format. If you are not yet subscribed, you can do so using the subscription form at the end of this article below.

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://trentinogenealogy.com/my-tree/