Genealogist Lynn Serafinn discusses the origins, history and expansion of the noble Borzaga of Cavareno, and famous Borzaga of the 20th century.

This article is also available as a 37-page downloadable, printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, charts, footnotes and resource list. Price: $3.75 USD.

Available in Letter size or A4 size.

CLICK HERE to buy this article in the ‘Digital Shop’, where you can also browse for other genealogy articles.

Introduction

Cavareno – An Overview

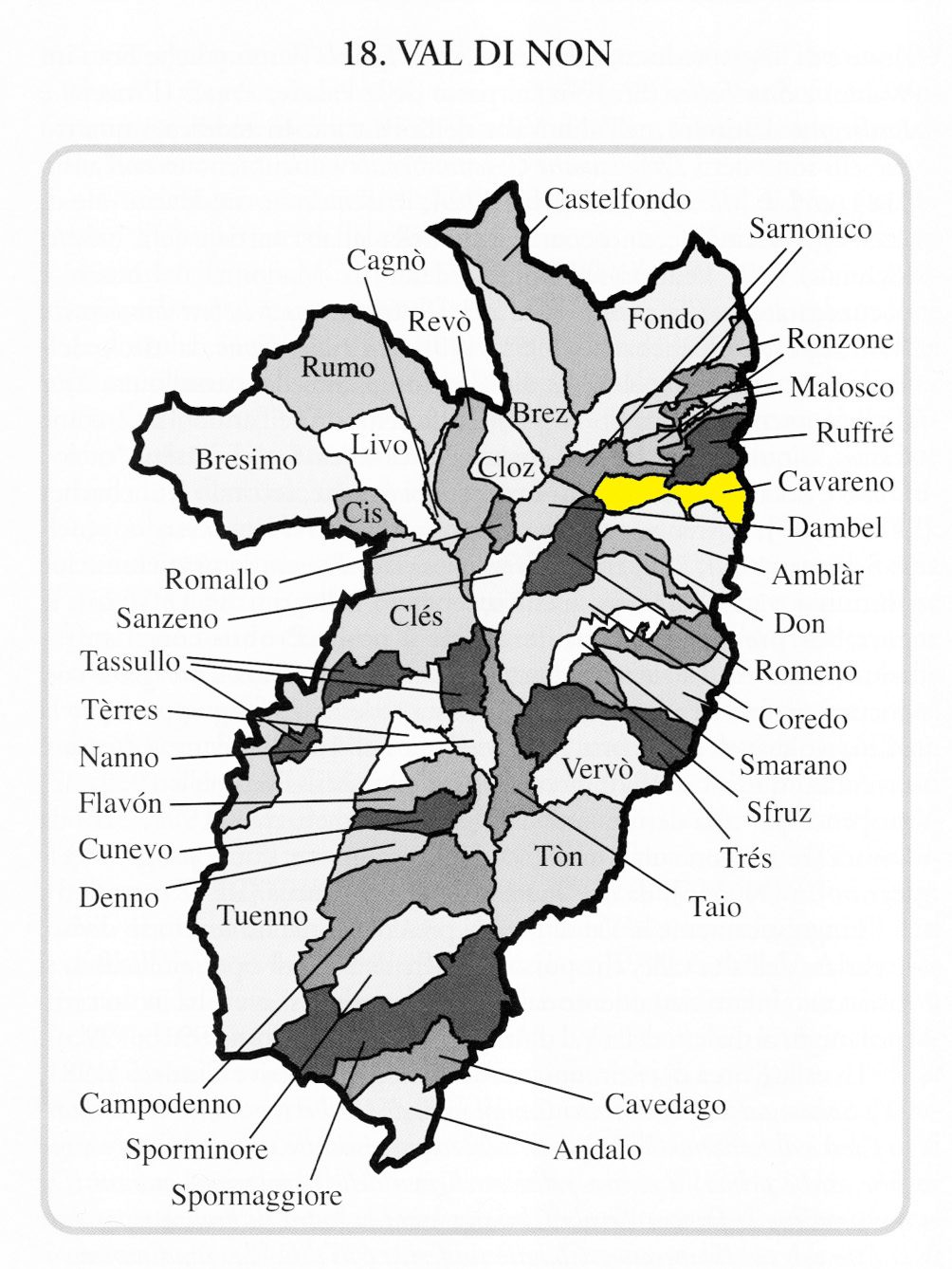

The charming village of Cavareno, highlighted in the map below,[i] lies in the north-eastern part of Val di Non in northern Trentino. Possibly already settled by the late Roman Empire, the dialect spoken in Cavareno is found only in a few other nearby villages, i.e., Sarnonico, Ronzone, Romeno (and its frazione Salter), Don, Amblar, and Malgolo.[ii] Perhaps this is part of the reason why we will often find marriages (and movement) between the families of Cavareno and these places.

This is the setting for the family we will be examining in this report: the BORZAGA.

Arriving in Cavareno in the early 1500s, the Borzaga would become one of three noble families associated with that village (the Campi and Zini being the other two).

In this report, we will explore their origins and early generation in Cavareno, their noble titles and their family occupation as notaries. Then, we will look at how some Borzaga lines settled in other parts of the province, all of whom can ultimately be traced back to the original settlers in Cavareno. Lastly, we will look at the lives of a few renowned personalities from more modern times, descended from this ancient family.

Sarnonico: The State of its Parish Records

To construct a genealogy for any family, it is first essential to get a good understanding of the state of surviving birth, marriage and death registers for that parish. Although an independent parish today, Cavareno (along with Malosco, Ruffré, Ronzone and Seio) was a curazia (‘daughter’ parish) of the larger parish of Sarnonico for many centuries. Hence, all baptismal records for Cavareno before 1855, as well as all marriages and deaths before the 20th century, will be found in the parish registers for SARNONICO.

Baptismal records

Although the baptismal records for the parish of Sarnonico begin in 1585, they do not flow in a continuous manner. The records stop abruptly and leap back and forth many times. To summarise what I have encountered:

- There is a GAP in the baptismal records from July 1609-January 1616.

- There are two random pages of baptisms from 1628-1629 mixed with the marriages in the 1620s. They are not duplicates, and do not appear in the baptismal register.

- I am convinced many baptismal records from the 1600s are missing, as I have often found evidence of people whose births ‘should’ be there, but they are not.

- Volumes 3 (1629-1650) and 4 (1650-1681) of baptismal records are organised in alphabetical order according to FIRST name. As such, they tend to leap around chronologically, and sometimes you will find things entered in the wrong place.

Marriage records

Similarly, although the Sarnonico marriage records begin in 1586, we again encounter many irregularities and gaps. Here is a summary of what you can expect:

- Volumes 1 and 2 of the marriage records contain indexes, but the priest who made the index for volume 1 has also noted that he was unable to read a great many of names, and hence about a quarter of the records are omitted from the index.

- Many of the pages referred to in the index are missing. Volume 1 of the marriages contains only pages 41-52 and 61-64 of the original register. Volume 2 starts on page 58; pages 63-64 are missing.

- Curiously, there is an index in Volume 2 that covers those missing pages, from which we can sometimes learn the surnames of some of the women, but nothing else.

- In Volume 1, there is ONE record from 1586, then it leaps to 1619, then back to 1587. After 1589, they stop and go to 1601 and forward (so there is about an 11-year gap here). Many records are extremely hard to read, as they tend to run into each other.

- The dates at the beginning of the volume 2 marriage records also leap around.

- SUMMARY OF GAPS IN SARNONICO MARRIAGE RECORDS: Dec 1589-Dec 1600; Nov 1612-Feb 1618; Dec 1619-March 1627; Aug 1638-Jan 1655.

Death records

Like most other Trentino parishes, the death records do not begin until the second half of the 1600s (in this case, 1664). The main issue is that the earlier registers do not appear to included infant/child deaths, which can make it more challenging to piece together families. While I have not yet found any significant gaps in the death records, I am convinced some records are missing, as I cannot find certain death records within the time frame they ‘should’ be found.

Origins

Linguistic Origins – Unsatisfactory Theories

Although several historians have offered theories on the linguistic origins of the surname Borzaga, I have not yet found any that are particularly convincing.

Linguistic historian Aldo Bertoluzza suggests that the surname Borzaga was derived from a place called ‘Borzago’ in Val Rendena.[iii] However, although there is a family named Borzaghini in Rendena who are undoubtedly connected to that village, I have found no historical connection between that family or village and the Borzaga of Val di Non.

As to the literal meaning of the surname, historian Ernesto Lorenzi says Borzaga (along with other surnames sharing the root ‘Borz’) may be derived from the antiquated male name ‘Burcio’, which is pronounced ‘Borz’ in Trentino dialect. Alternatively, he suggests it could also be a corruption of the German word/name ‘Swartz’ (having first been ‘Sborz’ and then ‘Borz’).[iv] But again, while these might apply to surnames such as Sborz, Borz, Borzi, etc., we find no such names among the family that start to be known as ‘Borzaga’ in the 1300s. Thus, I cannot accept these suggestions as likely explanations for the linguistic origins of the surname Borzaga.

Outliers – Pellizzano and Condino

For the sake of thoroughness, I should briefly mention that there were a few Borzaga ‘outliers’ appearing in the 1500s and 1600s, for which I currently have no explanation.

In a land sale agreement dated 24 August 1501, we find an Ognibene, son of the late Giacomo called ‘Borzaga’ of Pellizzano, in the southern part of Val di Sole.[v] I have checked the Pellizzano records that begin in 1626, but I have found no mentions of any Borzaga, and I cannot explain who this could have been.[vi]

Later, in a document dated 22 November 1595, we find a Nicolò, son of the late Angelo Borzaga da Condino, confirming he had received the dowry for his wife Flora Mazzola.[vii] Priest historian P. Remo Stenico also lists a priest named Nicolò Borzaga of Condino whose name appears in a record from 1693.[viii] Condino is in the Val del Chiese area of the Giudicarie Interiore, just north of Storo. Sadly, most of its archives were destroyed during World War 1,[ix] so I currently have no way to follow up this information.

For now, I will set aside these outliers as not being relevant to the topic of the current report, but it is possible that future research might reveal a connection between these and the Borzaga of Cavareno.

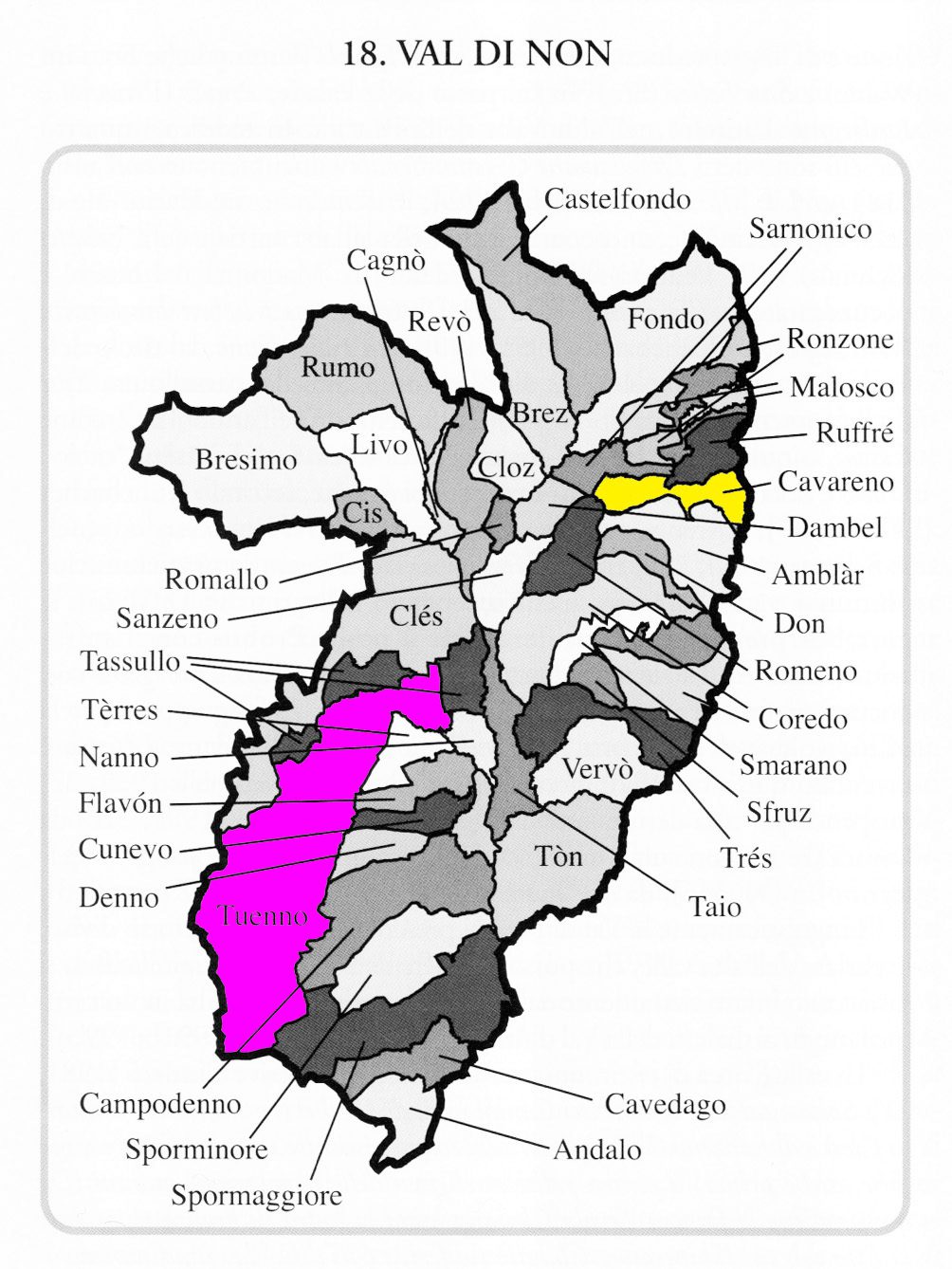

Geographic Origins of the Borzaga – Tuenno

There is much convincing evidence suggesting that the Borzaga of Cavareno were descended from the Lords of Tuenno in Val di Non.[x] [xi] [xii] Here, I have highlighted Tuenno on the map of Val di Non that I shared earlier, showing its position in relation to Cavareno. The distance on Google maps is roughly about 18 kilometres (about 11 miles) but bear in mind that this is all mountainous terrain.

In a work from 1955, Enrico Leonardi stated that the ultimate progenitor of the noble Borzaga family was ‘Giacomo de Borzaga’ of Tuenno, present at Castel Valer in 1211, who served as an attorney of Prince-Bishop Federico Vanga.[xiii] [xiv] Historian Paolo Odorizzi refers to this man only as ‘Giacomo of Tuenno’,[xv] as he was not truly a ‘Borzaga’, as the surname did not appear until about two centuries later.

Odorizzi explains that, while we have no documentation to definitively show us that Giacomo himself was a direct ancestor of the Borzaga, the Borzaga (along with the Concini and Cazuffo) were surely descended from Signore Bartolomeo I of Tuenno (ca. 1140-1210), as well as a later Bartolomeo II, who was certified as a notary in 1306.[xvi]

Thus, we see the foundations of what would eventually evolve into a legacy of notaries in the Borzaga family, which would endure for many centuries to follow.

First Appearance of the Surname

We first find the surname ‘Borzaga’ in the mid-1300s, in documents drafted by a Tuenno notary referred to as ‘Ser Bartolomeo, son of Benvenuto,[xvii] called Borzaga’. [xviii] [xix]

Paolo Odorizzi also tells us that this Bartolomeo (who was sometimes called ‘Tomeo’), was the grandson Sicherio of Tuenno, one of the Lords of Tuenno, who was also a notary.[xx]

We find Ser Bartolomeo in many high-ranking professional roles, such as the Vicario of Justice in Val Giudicarie (1360), Assessor of Stenico in Val Giudicarie (1375),[xxi] and the Assessor and Vicario of Val di Non and Val di Sole. He was also the notary who documented a truce between Valli di Non and Sole in 1371, [xxii] and was invested as a notary for Prince-Bishop George I von Liechtenstein at Castel Tuenno in 1400 and 1401.[xxiii] According to research by Odorizzi, Bartolomeo had two sons, Giovanni and Benvenuto Antonio (sometimes just called Antonio), who were also notaries.

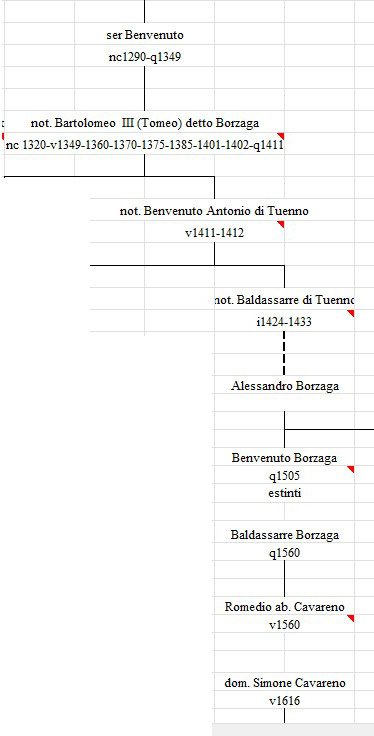

It is from this Benvenuto Antonio, he says, that the Borzaga of Cavareno are descended. Below, I have put a screenshot from a tree (in spreadsheet form) constructed by Odorizzi, showing the descending line from Ser Benvenuto to the early Borzaga in Cavareno. [xxiv]

Note, however, that there are several gaps in Odorizzi’s tree (which he indicates by dotted lines, or absence of vertical connecting lines), and this diagram does not show a continuous ancestral line, but rather a chronology of names for which we have evidence.

In fact, as we will examine shortly, there seem to have been multiple Borzaga lines in Cavareno in the late 1500s, which seems to infer more than one family group made the shift from Tuenno to Cavareno around the same time.

The Early Borzaga in Cavareno

Arrival of the Borzaga in Cavareno – When, Why and Who?

Writing in 1899, historian Carl Ausserer says the Borzaga left Tuenno for Cavareno by the year 1530. [xxv] [xxvi] Trusting Ausserer as a source, this date has been repeated in just about every other history I have read on Cavareno despite the fact that Ausserer gives no sources for this claim. He tells us only that the Tuenno notary (Alessandro) Compagnazzi, acting as the attorney for Borzaga family members who were still of minority age (i.e., not yet 25 years old), had arranged to have their Tuenno properties sold around this time.

The fact the attorney was acting on behalf of ‘minors’ seems to indicate their father was deceased. It is also important to bear in mind that the Guerra Rustica (Rustic War, or peasant revolt) had taken place just a few years earlier, in 1525. Perhaps both of these factors contributed to the family’s desire (or need) to make the shift to a new village.

Unfortunately, we do not seem to have any documents containing the names of the family members who made this move. We know there was a ROMEDIO Borzaga, son of the late BALDASSARE Borzaga, who was already living in Cavareno when he purchased some property there in 1560.[xxvii] But having carefully examined the very fragmented early parish registers for Sarnonico (which notionally begin in 1586), I feel fairly certain there had to have been more than one Borzaga household in Cavareno by this time, and that Romedio cannot have been the sole progenitor.

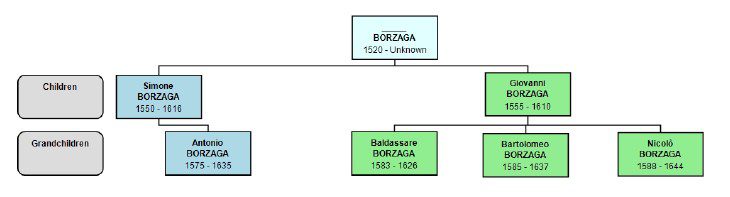

Early Patriarchs: Simone and Giovanni Borzaga

What we do know, via the surviving parish records for the Sarnonico, is that there were two Borzaga men – SIMONE and GIOVANNI – who were alive and having children in Cavareno during the last decades of the 1500s.

The male line of Borzaga descended from Simone (via his son Antonio) still exists today not only in Cavareno, but also in other parts of the province and beyond.

The male line descendants of Giovanni continued in Cavareno until the end of the 1700s, after which they appear to die out.[xxviii] There are still living descendants via some of the females in Giovanni’s line (some of my clients are descended from these female lines), but of course they do not carry the Borzaga surname.

None of the documents I have found record the name of Simone’s and Giovanni’s father(s). Although timing of the family in Cavareno would seem to suggest they would have been related to each other in some way (and also probably related to Romedio, son of Baldassare), I have found no documentation even suggestion what their relationship might have been.

My personal suspicion is that Simone and Giovanni were brothers, but this is based on an admittedly tenuous theory I have formed, as I will explain later in the section on nobility.

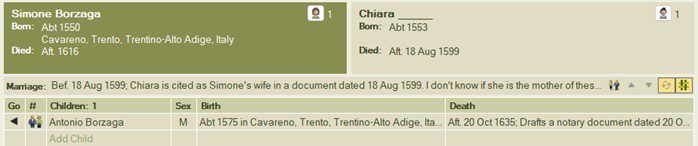

Patriarch 1: Simone Borzaga (Senior), Notary

Most likely born in Cavareno sometime around 1550, Simone followed in the footsteps of his Borzaga predecessors, and took on the profession of a notary.

We find the name ‘Simone Borzaga of Cavareno, imperial notary’ as the author of numerous legal documents between 1594-1603.[xxix] [xxx] Unfortunately, none of the documents I have not found includes name of Simone’s father, but as he is always referred to as ‘of Cavareno’, we can presume he was born there and not in Tuenno.

We know Simone had at least one son – ANTONIO Borzaga – who was also a notary, and who would be the recipient of many noble honours. We will discuss the activities of Antonio in some detail later.

We find the name of Simone’s wife, Chiara, in a document drafted in Cavareno on 18 August 1599. In that document, Simone and Chiara agree to give an annual payment of rye on a meadow which was part of Chiara’s dowry as payment to a Giovanni Giacomo Mazza; in exchange, Simone gives his wife a guarantee for the same value from his own properties.[xxxi] Looking at the timing of this document, I am fairly certain Chiara would have been Simone’s second wife, and not the mother of his son Antonio.

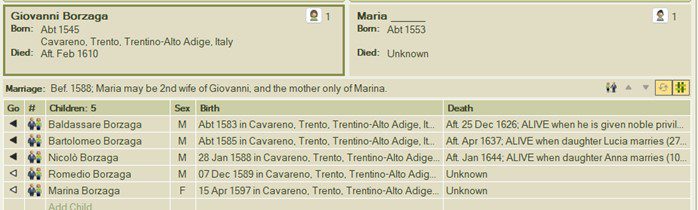

Patriarch 2: Giovanni Borzaga

The surviving parish registers contain baptismal records for two of Giovanni’s sons – NICOLÒ (1588) and ROMEDIO (1589). Neither of these records mentions the name of their mother. The baptismal record of a daughter named MARINA in 1597 gives her mother’s name as Maria, but the wide gap between her birth and that of Romedio suggests Maria was Giovanni’s second wife.

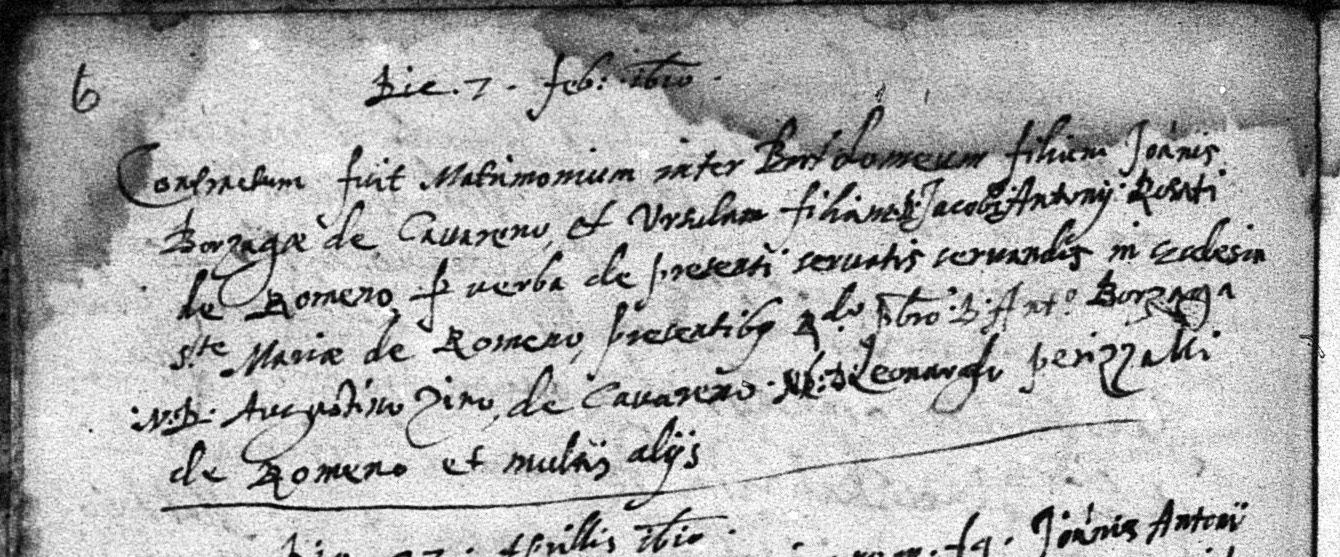

In addition to the three children whose births are recorded in the parish register, we also know Giovanni had a son named BARTOLOMEO (evidently born before the beginning of the records), who married an Orsola Rosati (daughter of Giacomo Antonio) of Romeno on 7 February 1610:[xxxii]

Later, when we discuss a diploma of nobility granted to the Borzaga in 1626, we will learn of a third brother named BALDASSARE, again born sometime before the beginning of the records.

Baldassare, Bartolomeo and Nicolò all grew up to have families of their own. I have no further information about Romedio or Marina.

More Outliers

Aside from Giovanni and Simone, we do find a few instances of the other Borzaga in Cavareno in the early 1600s, but none of these lines appear to have endured.

We find, for example, a MICHELE Borzaga, married to a Lucia, who had twin boys named Pietro and Giacomo on 15 May 1606.[xxxiii] Aside from this baptismal record, I have can find no further mention of Michele or his sons, and I have no idea if or how they are connected to Giovanni and Simone.

A bit later, we find a ‘NICOLÒ Bodessaroli called Borzaga’, married to a Maria, who had a daughter Cattarina (born 27 December 1624)[xxxiv] and a son Baldassare (born 8 May 1628).[xxxv] We find this same Nicolò named as the ‘son of the late Baldassare “Bodessaroli” of Cavareno’ in a payment agreement dated 25 April 1625 in Sarnonico. [xxxvi] In that document, it says a DIFFERENT Nicolò Borzaga of Cavareno was the curator (legal representative) for the other Nicolò ‘Bodessaroli’. After these citations, we see no further mention of the soprannome ‘Bodessaroli’, nor any further mention of Nicolò ‘Bodessaroli’ Borzaga or his children. Thus, we have to assume this line died out.

Still, the records regarding the short-lived ‘Bodessaroli’ may contain clues to the ancestry of the Borzaga lines that did survive:

- The simple fact that we see a soprannome in use makes it clear that there was more than one Borzaga line present in Cavareno in the early 1600s. We see this clearly in the 1625 document where there are two different men named Nicolò Borzaga – one with the soprannome, and one without. (I am reasonably certain the ‘non-soprannome’ Nicolò was the son of Giovanni).[xxxvii]

- As none of the descendants of Giovanni and Simone used the soprannome ‘Bodessaroli’, they were clearly NOT from the same branch as the ‘Bodessaroli’ Borzaga.

- The fact that ‘Nicolò Bodessaroli called Borzaga’ was the son of a Baldassare makes me wonder whether he was a brother of the afore-mentioned Romedio, whose father was also a Baldassare Borzaga (although the document we have for Romedio does not mention a soprannome).

- If this was the case, knowing that Giovanni and Simone were from a different line, we might then theorise that they were NOT the sons of Romedio, but from a different Borzaga whose name we do not yet know.

For now, we have to set these lines of inquiry aside, holding them in the back of our minds as possible clues that might reveal more information as more documentation comes to light.

The Noble Borzaga

Noble Title and Stemma – 1615

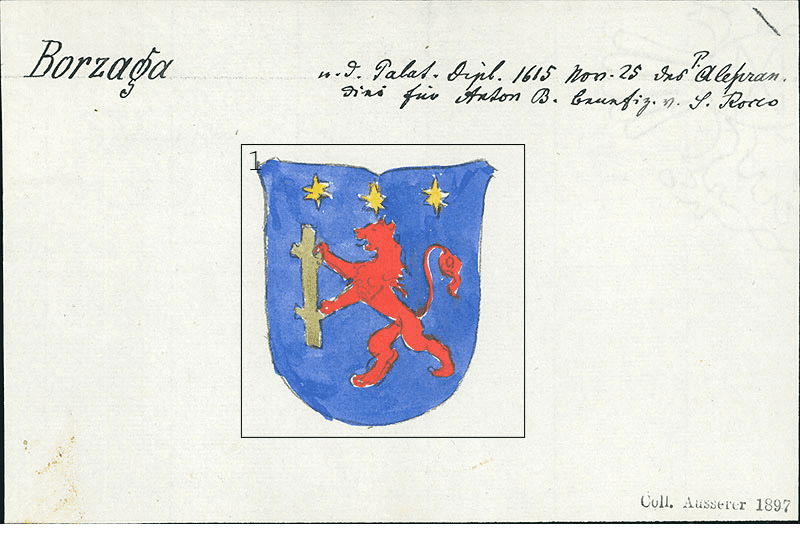

Although the Borzaga had already come from a noble lineage, they attained additional titles of nobility in the 17th century. In the ‘Ausserer Collection 1897’ preserved at the Tiroler Landesmuseen in Innsbruck, there is an illustration of a Borzaga family stemma (coat-of-arms), said to have been granted to one Antonio Borzaga in 1615. The inscription on the card says, ‘Palatine Diploma, 25 November 1615 (granted) by P. Alessandrini to Anton (i.e., Antonio) B (Borzaga):[xxxviii]

It is somewhat perplexing, however, why Carl Ausserer makes no mention of this award in his 1899 book. I wrote to the Landesmuseen in Innsbruck, and one of their archivists told me via email that they have no further reference to that diploma in their library other than this card. Moreover, neither Leonardi nor Tabarelli de Fatis and Borrelli mention this 1615 title in their books.

Nonetheless, despite the scanty information about this 1615 award, I am confident that the ‘Antonio Borzaga’ in question was Antonio Borzaga, notary, son of Simone (‘Patriarch 1’), as Antonio’s son Simone, and all of Simone’s descendants, are consistently referred to as ‘noble’.

Although Antonio was born before the beginning of the surviving parish registers, we can estimate from dates of the legal documents he drafted that he was most likely born sometime around 1575.

Variants on the Stemma

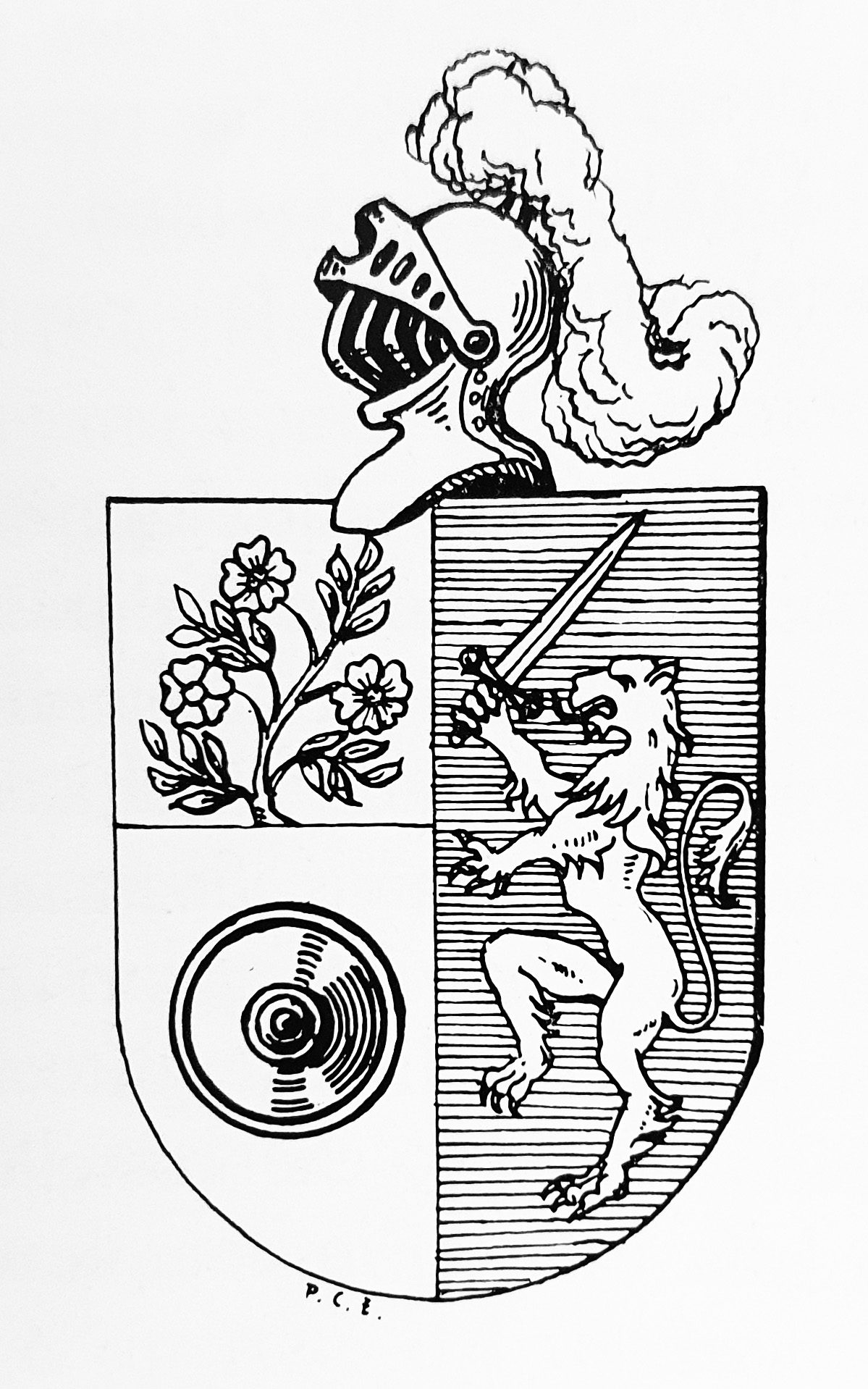

The main component of the 1615 stemma is a red lion standing upright, holding an uprooted tree, with three gold stars overhead. Tabarelli de Fatis and Borelli show a variant of this where the same lion is also in the crest atop the main shield:[xxxix]

Endrizzi shows us yet another variant, where the lion is holding a sword instead of a tree, with other elements now depicted on the left side of the shield:[xl]

Authentication and Extension of Title – 1626

After a noble title has been granted, the need would often arise for them to be ‘confirmed’ or ‘authenticated’ by a representative of the empire or the principality. Usually, such confirmations would become necessary if the original recipient of the title had passed away, and future generations required proof of their inheritance.

But sometimes, a confirmation would be needed if noble privileges were to be extended to ‘parallel’ members of the family (brothers, cousins, etc.) who had not been named in the original diploma, and who were not direct heirs (children, grandchildren, etc.) of the original recipient. This appears to have been the scenario for the Borzaga in 1626.

Leonardi tells us, ‘On 25 December 1626, the Prince-Bishop, having seen the caesarean privileges previously granted to the family, authenticates the privileges and grants the stemma.’[xli] Thus, he infers there was an earlier title (presumably the one from 1615), but he provides us with no details about it.

Tabarelli de Fatis and Borelli give us some additional information, saying that the stemma was granted on 25 December 1626 by Count Palatine P. Alessandrini de Neuenstein of Trento to Antonio, Baldassare, Bartolomeo and Nicolò Borzaga, brothers, of Cavareno.[xlii]

After assessing and comparing these descriptions alongside what we see in the parish records and notary documents, I believe none of these fragmented statements gives the complete picture. Moreover, I think some of the wording in the books is misleading, if not incorrect.

About the title

It is clear that P. Alessandrini de Neuenstein who awarded the title and stemma to the Borzaga was a ‘Count Palatine’. This title was once associated with one of the most illustrious positions of the early Middle Ages in the kingdoms of the Franks. The original job of the Palatine Count was to judge all the cases that had appealed to the sovereign’s tribunal, and then to bring to the King’s knowledge only those judgments that he considered most important. But over the centuries, the title lost its original importance, and by the early 1600s, it was often little more than a token granted by the emperor in exchange for loyalty (or money). Nonetheless, the title still carried a certain amount of social prestige.

By saying ‘caesarean privileges’ Leonardi seems to infer the Borzaga had been granted the title of ‘Count Palatine’, but this was not the case. Such a title would have been granted by the Holy Roman Emperor, not by another Count Palatine. Moreover, while the Borzaga were referred to as ‘noble’ in the parish registers, they are never referred to as ‘Conte Palatino’.

About the recipients

I also believe the reference to ‘Antonio, Baldassare, Bartolomeo and Nicolò Borzaga, brothers’ may be slightly incorrect. Based on what I have been able to ascertain, I am fairly confident that the term ‘brothers’ refers to the last three men, and NOT to the original Antonio:

- We know from a document from 1616 that the notary Antonio Borzaga was the son of the notary Simone (Patriarch 2).[xliii] However, I have found no evidence that Simone had any other sons, nor have I found evidence of a second Antonio.

- As discussed earlier, we know from parish records that Giovanni Borzaga (Patriarch 2) had two sons named Bartolomeo and Nicolò. The parish registers also show us a Baldassare Borzaga who had a son named Giovanni on 18 January 1616.[xliv] As this appears to be his only child, it seems logical to assume Baldassare was another son of Giovanni.

Thus, Antonio Borzaga CANNOT be a brother of Baldassare, Bartolomeo and Nicolò, as he was not the son of Giovanni.

Based on this information, I am inclined to re-interpret the wording by Tabarelli de Fatis and Borelli as: ‘the stemma was granted to Antonio (Borzaga) [and to] Baldassare, Bartolomeo and Nicolò Borzaga, brothers.’

My theory

My working theory is that the patriarchs Simone and Giovanni were brothers. This means Antonio the notary would have been the first cousin, not the brother, of the other three recipients (Baldassare, Bartolomeo and Nicolò).

One possible reason why this title may have been extended to Antonio’s cousins is the fact that he appears to have had no living siblings. Moreover, he himself had only one surviving son – Simone, born 29 November 1603.[xlv] Simone, who was still a minor when the awards were granted, would have automatically inherited his father’s title and stemma, and thus there was no need to include his name in these diplomas. But were this Simone to die young, the title would go extinct when Antonio died.

Although that didn’t actually end up happening (in fact, Simone’s descendants continue to this day), in 1626 it would have made perfect sense that the family wanted to ensure the continuation of their noble privileges by requesting they be extended to include Antonio’s cousins.

Below is a stripped-down diagram, showing this configuration. To make the chart easier to understand, I have removed the names of all wives and daughters, as they are not relevant to the issue of the noble title. I have also removed Giovanni’s son Romedio[xlvi], who was most likely deceased before 1626 as he was not included in the diploma of nobility.

Article continues below…

Six Generations of Borzaga Notaries

In his 1999 publication, P. Remo Stenico lists four Borzaga notaries from Cavareno; but in constructing a Borzaga genealogy using the parish register, I have identified others Stenico did not include in his study.[xlvii] In fact, when we work through the families methodically, we discover an unbroken chain of notaries from father to son for six generations, as well as another cousin in generation 6:

| GENERATION | RELATIONSHIP | NAME/DATES |

| 1 | PATRIARCH | Simone (b. about 1550) |

| 2 | Son | Antonio (b. about 1575) |

| 3 | Grandson | Simone (b. 29 Nov 1603) |

| 4 | Great-grandson | Antonio (b. 28 June 1627; d. 24 May 1704) |

| 5 | 2X great-grandson | Giovanni Battista (b. 22 June 1682) |

| 6a | 3X great-grandson | Carlo Antonio Martino (b. 13 November 1709; d. 4 December 1764) |

| 6b | 3X great-grandson | Pietro Antonio (b. 14 December 1726; died 21 June 1803). NOTE: he was the 1st cousin (not the brother) of Carlo Antonio Martino. |

We have already looked briefly at Simone ‘Senior’, so let us now look at the professional careers of his notary descendants.

Generation 2: Antonio, son of Simone

Most likely born around 1575, Simone’s son Antonio is found actively practicing his profession as a notary at least between December 1602[xlviii] and October 1631[xlix]. As he typically signed his name simply as ‘Antonio Borzaga, notary of Cavareno’, we might never have known who his father was, if it were not the Carta di Regola (Charter of Rules) for the comune of Seio which he drafted on 3 March 1616, in which he signs his name as ‘Antonio, son of egregio domino Simone Borzaga of Cavareno, Val di Non, Diocese of Trento.’[l] While the honourific words ‘egregio domino’ can be loosely translated as ‘the esteemed gentleman,’ the term ‘egregio’ is nearly always an indication the man (in this case, his father) was a notary.

As already mentioned, this is surely the Antonio who had been granted the noble title and stemma in 1615 and again in 1626. We find his descendants referred to as ‘noble’ in the Sarnonico records, especially in the indices.

Generation 3: Simone, son of Antonio (grandson of Simone Senior)

Born 29 November 1603 to Antonio and his wife Margherita,[li] Simone is not listed in Stenico’s book of notaries. However, he is called ‘egregio’ in baptismal record of daughter Margherita (11 September 1630)[lii], and ‘spectabilis’ in marriage record of daughter Barbara (28 April 1667).[liii] These honourifics are used only when referring to notaries.

On the Archivi Storici website, we find several references to a Simone Borzaga, notary, during this era; however, some of the earlier documents (especially one dated 1627) may refer to his grandfather, as I am unsure as to when the elder Simone passed away.[liv] [lv] [lvi] [lvii]

Generation 4: Antonio, son of Simone (great-grandson of Simone Senior)

Born 28 June 1627, the next Borzaga notary was another Antonio, the eldest son of Simone (b. 1603) and his wife Maria.[lviii]

His first marriage took place on 27 November 1664, when he was already 36 years old. His bride was the noble Maria Sofia Zini, who was nearly 14 years his junior.[lix] Their marriage record contains some interesting details. First, we notice that Antonio is referred to as ‘Nobilis Magister Philosophia’, which literally means ‘Noble Master (or teacher) of Philosophy.’ While this could mean he was a teacher, it more likely refers to his educational degree. The record does not say he is a notary, but it does refer to his father Simone as ‘spectabilis’ (indicating he was a notary). We also learn that he and Maria Sofia, who is also referred to as nobility, were granted a dispensation for 3rd grade consanguinity. This means they were 2nd cousins (i.e., they shared great-grandparents). Unfortunately, the records do not go back far enough to help us establish this connection, but it does tell us that there was already early intermarriage between these two noble families of Cavareno.

Soon after his marriage, we find him as the notary who drafted several level documents between the years 1660-1671.[lx] [lxi] [lxii] [lxiii] In the private collection of the noble Thun family (now held at the Archivio Provinciale di Trento), we also find six letters sent from Antonio to Count Cristoforo Riccardo Thun, written between the years of 1659-1667.[lxiv]

A few months after the birth of their fifth child, Maria Sofia passed away at the age of 35.[lxv] Soon after, Antonio remarried Veronica Rosina, with whom he father 6 more children. He died on 24 May 1704, just a month before his 77th birthday.[lxvi]

Generation 5: Giovanni Battista, son of Antonio (2X great-grandson of Simone Senior)

As we would have expected, Antonio and Maria Sofia did have a son named Simone, but he died when he was still in his teens, so he never lived to learn the family profession. Instead, it was Giovanni Battista Borzaga, the eldest son of Antonio and his second wife Veronica Rosina, who would carry on the tradition.

Born 22 June 1682[lxvii], we first find an indication of Giovanni Battista’s profession when he is referred to as ‘spectabilis’ in the baptismal record of his daughter Maddalena Veronica, who was born 4 May 1726.[lxviii] Stenico cites ‘Giovanni Battista Borzaga, son of Antonio’ as being active between the years 1731-1734,[lxix] but I have also found a document drafted by him in 1745.[lxx]

In 1732, Giovanni Battista held the office of general sindaco of Valli di Non and Sole together with the noble Giovanni Nicolò Bevilacqua and Giuseppe Maffei.[lxxi]

Although not specifically related to his practice as a notary, there is also a record held at the Municipal Library in Trento, in their Archivi di famiglie (Archives of families), dated 26 August 1721, which is an agreement stipulated between the prelate of the Provost of San Michele all’Adige and Giovanni Battista Borzaga, along with his two younger brothers, Tommaso (i.e., Tommaso Romedio) and Antonio. [lxxii]

Although not listed in Stenico’s book, we have some news of another brother, Pietro Antonio (born 19 October 1687)[lxxiii], who became a priest. Described as the ‘noble Rev. Pietro Antonio Borzaga’, he was the godfather of his niece Veronica Teresa Margherita Borzaga (eldest child of his youngest brother, Antonio) on 11 October 1716.[lxxiv]

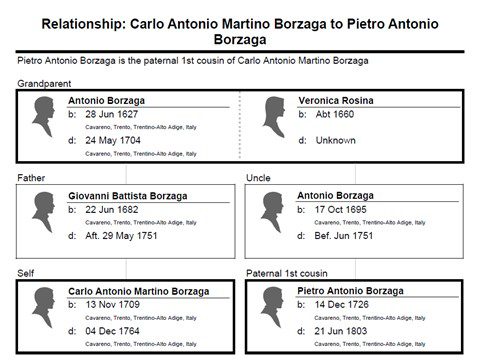

Generation 6: Carlo Antonio Martino and Pietro Antonio (3X great-grandsons of Simone Senior)

At this point, we now find two Borzaga notaries, both the 3X great-grandsons of Simone Senior.

Both grandsons of Antonio Borzaga and Veronica Rosina, the first of these – Carlo Antonio Martino Borzaga – was actually 17 years senior to first cousin and professional colleague, Pietro Antonio Borzaga.

Although baptised Carlo Antonio Martino on 13 November 1709,[lxxv] the elder cousin was generally known only as Carlo or Carlo Antonio. Stenico cites him as being active as a notary between the years 1740-1749,[lxxvi] but he is referred to as a notary in the baptismal records of his children as early as August 1731.[lxxvii] We also find him as the notary who recorded a criminal trial in Cles between the years 1750-1759.[lxxviii] He fathered at least eight children with his wife Lucrezia Cattarina, none of whom appear to have been notaries. He passed away on 4 December 1764.[lxxix]

Baptised 14 December 1726, Pietro Antonio (sometimes known simply as Pietro) was the son of Carlo Antonio’s paternal uncle Antonio.[lxxx] Sometime before 1751, he married the noble Maria Veronica Antonia Bartoli of Cornaiano in South Tyrol, with whom he fathered at least 11 children. Stenico cites his professional career as a notary as spanning nearly half a century, from 1749-1797.[lxxxi] He is consistently referred to as a notary in the baptismal records of his children, beginning in 1751.

As with Carlo Antonio, I can find no notaries amongst Pietro Antonio’s sons, and the impressive legacy of Borzaga notaries appears to end with his death at the age of 76, on 21 June 1803.[lxxxii]

Expansion: Beyond Cavareno

Over the centuries, some branches of the Borzaga would eventually expand and settle in other places, both near and far from their home in Cavareno.

With the exception of one case where records appear to be missing, I have managed to trace every one of these lines back to ‘Patriarch 1’, i.e., Simone Borzaga, Senior, notary. The descendants of ‘Patriarch 2’ (Giovanni Borzaga) appear to have stayed in Cavareno until they died out around the end of 1700s.

Below is an overview of each of these lines, including a look at their ‘founding parents’.

Borzaga in Ronzone

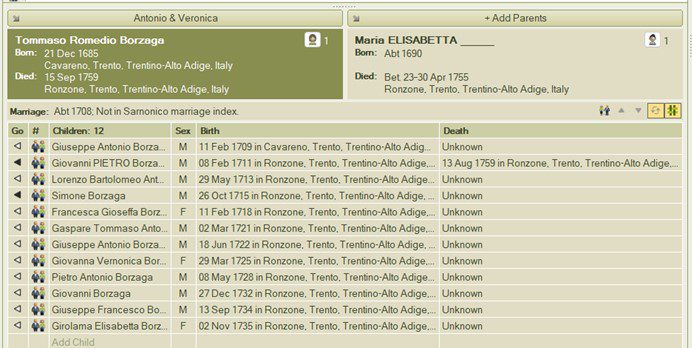

One of the most prominent sub-branches of the Borzaga are those in Ronzone, another curate of the parish of Sarnonico. This branch began when Tommaso Romedio Borzaga (born 21 December 1685)[lxxxiii] and his wife Maria Elisabetta moved from Cavareno to Ronzone sometime between 1709-1711.

Tommaso Romedio was the son of the notary Antonio Borzaga (1627-1704), and younger brother of the notary Giovanni Battista Borzaga (b. 1682). Thus, he was the 2X great-grandson of the notary Simone Borzaga ‘senior’.

I mentioned Tommaso earlier, in the section on his brother Giovanni Battista, when I referenced a document from the Trento Municipal Library.

Parents of at least 12 children (all but the first was born in Ronzone), they are the ancestral parents of the all the Borzaga of Ronzone, a line which continues to this day.

Borzaga in Brez

Situated just to the west of Sarnonico, the nearby parish of Brez was home to many Borzaga over the centuries.

The earliest Borzaga I have found in Brez was not a family, but the priest Antonio Borzaga from Cavareno, who served as the parroco (pastor) of the parish of San Floriano in Brez from 1634 until 1651.[lxxxiv] Unfortunately, I don’t know who his parents were, and he was either born before the beginning of the Sarnonico records, or his baptismal record is missing.

Later, Brez became the home of two different ‘waves’ of Borzaga families, arriving there at different periods of time, one from Cavareno, and the other from Ronzone.

Wave 1: Family of Andrea Borzaga and Maria Cattarina Bertoldi

The first ‘wave’ began when an Andrea Borzaga of Cavareno married a Maria Cattarina Bertoldi of Brez in 1695.[lxxxv] Sadly, Andrea’s father’s name is not mentioned in the marriage record, nor in the baptismal records of any of his children, nor in his 1745 death record, when he is said to be about 80 years old.[lxxxvi] I have also looked exhaustively in the Sarnonico records for an Andrea or Giovanni Andrea who would have been born around the right time, but I was unsuccessful. Although the couple had at least six children, only one son (Baldassare) grew up to have a family, while a younger son (Giovanni Andrea) became a priest.

Andrea and Maria Cattarina’s younger son Giovanni Andrea was born in Brez on 15 May 1706.[lxxxvii] Rather than marrying, Giovanni Andrea became a Catholic priest.[lxxxviii] At the age of 33, he became the curate (equivalent of a pastor) of Proves in South Tyrol, where he served for 27 years.[lxxxix] [xc] He died 25 Feb 1781, when he was nearly 75 years old.[xci] In addition to mentioning his former role as the curate of Proves, his death record also says he a beneficato for a member of the Ruffini family[xcii], and the founder of the ‘Benefici Borzaga’ apparently another legacy of funding for local priests.

Their elder son Baldassare was born in Brez on 24 December 1698.[xciii] He married Maria Maddalena Betta of Cagnò (parish of Revò) on 26 April 1729.[xciv] After suffering a massive stroke, he died at the age of 45 on 13 November 1744,[xcv] four months before the birth of his last child (who was named Baldassare in his memory).

The couple had at least 6 children together, including three sons. Of these, the only one who appears to have lived to adulthood is their son Giovanni Luigi, who was born 1 February 1736.[xcvi] Although he married twice, he does not appear to have had any children of his own, as the marriages were

Giovanni’s first wife, Domenica, who died 26 January 1791 at the age of 64, was apparently nearly a decade older than he was.[xcvii] I haven’t found a marriage record for them, but it is possible it took place when she was already widowed and beyond childbearing age. A few months later, on 29 April 1791, he married his second wife, Maria Antonia Zuech, widow of Romedio Gilli.[xcviii] Again, the marriage produced no children (she was already 38 and he was 56), but the couple lived out their days together.

With the death of Giovanni on 6 March 1809[xcix], this first ‘wave’ of the Borzaga in Brez died out.

Wave 2: Family of Tommaso Antonio Cirillo Borzaga and Maria Flor

A few years before the death of the last Borzaga from the ‘first wave’, another Borzaga line established itself in Brez, this time coming from the Ronzone line. The founding father of this second wave was Tommaso Antonio Cirillo Borzaga, who was born in Ronzone on 30 March 1778, the son of Tommaso Romedio Borzaga and Maria Domenica Gius.[c] He was the 5X great-grandson of the notary Simone Borzaga ‘senior’.

This younger Tommaso married Maria Flor of Brez on 25 September 1800,[ci] and opted to settle in his wife’s home village to raise their family. However, after his wife Maria Flor died Brez on 25 March 1848,[cii] Tommaso moved back to his native village of Ronzone, where he passed away from respiratory issues on 3 March 1853, just a few weeks before his 75th birthday.[ciii]

Of the couple’s nine children, three were sons; the youngest (Nicolò) died in infancy, but the other two sons (Baldassare and Giovanni), went on to have many children of their own, all born in Brez. Baldassare’s line does not seem to have endured, as five of his six sons died as children or young adults.[civ] Giovanni’s descendants continued well into the 20th century, and we find references to 10 of his great-grandchildren cited in the indices of the Brez register, who were born between 1935-1952, although all but one of the males died in their teens. [cv]

One other great-grandson and many great-granddaughters were still alive as of 1965; some of these may still be alive today, so I cannot share specific information about them, although the Cognomix website does not show any Borzaga families living in Brez today.[cvi] Writing in 2005, however, author Bruno Ruffini alludes to this Borzaga line in his book L’Onoranda Comunità di Brez, saying that they arrived in Brez the second half of the 1700s, and have since gone extinct.[cvii] If this is indeed the case, the Borzaga surname would have gone extinct in Brez sometime within the past generation.

Borzaga in Amblar

On the Nati in Trentino website, you will find a line of Borzaga living in Amblar beginning in 1858. As Amblar is a curate of the ‘mother’ parish of Romeno, you will find these births register in both Amblar and Romeno.

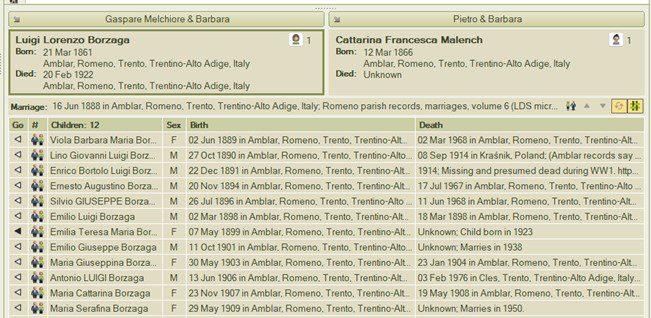

The founding parents of the Amblar line are Gaspare Melchiore Borzaga of Cavareno and Barbara Pellegrini of Amblar, who married on 24 January 1857[cviii]. Born in Cavareno on 15 January 1828, Gaspare was the 6X great-grandson of the notary Simone Borzaga ‘senior’.[cix]

Gaspare and Barbara had only 6 children, as Gaspare died from pulmonary tuberculosis at the age of 40.[cx] Although at least two of their four sons died in infancy, their son Luigi Lorenzo had at least 12 children with his wife, Cattarina Francesca Malench (also of Amblar).

Of their five daughters, two died in infancy (Maria Giuseppina and Maria Cattarina). The baptismal records of the other three daughters tell us they all married,[cxi] but of course they did not pass on the Borzaga surname.

Of their seven sons, one died in infancy, and two (Lino and Enrico) perished on the Eastern front during World War 1, when they were still young, unmarried men.[cxii] The baptismal records for three of the other sons (Ernesto Augustino, Silvio Giuseppe, Emilio Giuseppe) tell us they all married.[cxiii] The Cognomix website says there are presently for Borzaga families currently living in Amblar, and another in Don (also part of the parish of Romeno),[cxiv] so I presume these are the descendants of these sons.

Borzaga ‘On the Road’: Alta Garda, Rendena, Giudicarie, Trento

Towards the end of the 19th century, we find a Borzaga who not only appears to have had an interesting life travelling throughout the province, but he was also the father and grandfather of two widely renowned Trentino personalities. Here is a map showing all the ‘stops’ this family made over a 20-year period:

The man in question is BASILIO GIAMBATTISTA BORZAGA. Born in Ronzone on 29 November 1856, Basilio was the second son of Giovanni Battista Antonio Borzaga and Marcellina Maria Gius.[cxv] He never really knew his father, however, as Giovanni Battista died tragically from a serious fall when Basilio was only 3 years old.[cxvi]

Basilio married Cattarina Thaler of Bronzolo (South Tyrol) on 7 November 1883.[cxvii] Although the marriage took place in Ronzone, the record tells us that Basilio was then living in Arco, which is about 90 km to the south (56 miles) in Alta Garda, just above Lake Garda, in the southernmost part of the province of Trento (see map above).

Cattarina was obviously pregnant at the time, as only three months later, she gave birth to their first child, Augusto Basilio Borzaga, who was born in Arco on 3 February 1884.[cxviii] Augusto, who was better known as GUSTAVO BORZAGA grew up to become a famous painter. We will look at his life and work a bit later in this report.

The following year, we find the family has travelled north to Strembo, in Val Rendena in the northern part of Val Giudicarie Interiore, where their daughter Giuseppina Marcellina is born.[cxix] The record also has a margin note telling us she died on 29 August 1940, but it does not give a place of death or whether she had been married.

At first, I was unsure whether Giuseppina Marcellina was the daughter of Basilio or his brother Giuseppe Giambattista, because the record says the child’s father was ‘Giambattista Borzaga, son of the late Giambattista and the living Marcella’. It also says the mother’s name is Cattarina Furletti (which is similar to Cattarina Toller’s mother’s surname of Furtarelli). It specifies that the family came from ‘Ronzone in Val di Non’. Although Furletti is a surname in nearby Preore, my colleague James Caola, who has done extensive research with the Rendena parish records, has found no such marriage between a Borzaga and a Furletti either in Preore or in the Rendena parishes. Additionally, the record says the godparents were Giuseppe Borzaga and Marcellina Borzaga, ‘uncle and aunt of the child’. Surely the ‘uncle’ godfather must be Giuseppe Giambattista Borzaga, the elder brother of Basilio, which confirms to me the parents must be Basilio Borzaga and Cattarina Toller. Moreover, the ‘aunt’ named Marcella is surely referring to the child’s grandmother, as we know she was still alive (I will explain more about this shortly).[cxx] Thus, I presume the record is simply full of errors due to the priest being unfamiliar with this family, as they apparently were there only for a brief time.

A year and a half later, we find the family in Carisolo, also in Val Rendena, a bit north of Strembo and not far from Pinzolo. There, another son was born, Urbano Cornelio Pietro, on 25 February 1887. [cxxi] Known alternatively as Urbano Cornelio and Cornelio, he served in the Austro-Hungarian Army during World War 1.[cxxii] His baptismal record tells us that married a Carlotta Bertotti at the Duomo of San Vigilio in the city of Trento on 13 Jul 1914. The Nati in Trentino database tells us the couple had two children, both born in Trento, in 1914 and 1920, respectively. He passed away at the age of 77 on 30 September 1964.

After the birth of Urbano, Basilio and Cattarina moved again. This time, they went south to Preore in Val Giudicarie, where two more two daughters were born – Marcellina Pierina Maria Elisabetta (30 June 1888) and Elvira Daria Maria (29 December 1889). In the baptismal record for Marcellina, we see the godmother is ‘Teresa Borzaga, aunt’.[cxxiii] This surely refers to Basilio’s younger sister, Domenica Teresa Borzaga, who was born in Ronzone on 18 June 1859, and was apparently still unmarried although in her late 20s. The following year, in Elvira’s baptismal record, we see her godmother is ‘Marcellina Borzaga’, again surely referring to Basilio’s widowed mother.[cxxiv]

After Preore, the family makes one more shift to Tione di Trento, which is only a short distance from Preore, still in Giudicarie Interiore. Here, Basilio and Cattarina had four more children: two daughters and two sons. The only one of these for whom I currently have any information is their son and youngest child, Eduino Borzaga. Born in Tione on 29 August 1899, Eduino became a Trento-based lawyer, who was active in his profession at least through the end of 1958.[cxxv] Eduino’s daughter was the prolific author and poetess GIOVANNA BORZAGA (1931-1998). Again, we will look at her life and achievements in the next section of this report.

To sum up the movements of Basilio and Cattarina’s family, here is a screenshot showing the births of their children in the various villages, as well as their death dates/estimates, where known:

We know the family stayed in Tione at least until 1902, because this is where we are told Basilio’s widowed mother Marcellina passed away on 26 May 1902.[cxxvi] When I first saw this notation in her records, I was bewildered as to why she would have died in Tione, but it now is clear that Marcellina and her other two (adult) children accompanied Basilio and his family throughout their travels.

Sometime after his mother’s death, Basilio returned to his native village of Ronzone, where he passed away on 12 September 1915. Only from his death record do learn he was a retired travelling schoolteacher.[cxxvii] Thus, we finally have an explanation for Basilio’s interesting and unconventional lifestyle.

I feel it also gives us some insight as to how so many skilled and educated children and grandchildren came from one family, and why at least three children from this family left rural life forever, settling in the city of Trento.

Five Distinguished Borzaga from the 20th Century

Gustavo Borzaga – Painter

Born in Arco on 3 February 1884,[cxxviii] the renowned painter GUSTAVO BORZAGA (born Augusto Basilio Borzaga) was the eldest son of Basilio Borzaga and Cattarina Thaler.

Although Gustavo’s family left Arco when he was only a few months old, he was nonetheless hailed as being a ‘native’ of that comune in an exhibition held in 2004 at the Palazzo dei Panni, the seventeenth-century residence of Count Emanuele d’Arco.[cxxix] In the promotional material for that exhibit, we are told that Gustavo’s talent was discovered when he was a mere 14 years old, when the artist Angelo Comolli, a professor at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera in Milano, came to Tione in 1898 to paint some frescoes at the church there. Comolli took the young Gustavo back to Milano with him as his student. By the time Gustavo was 22, we find him living in the city of Trento, working on numerous commissioned frescoes in many palazzi and public buildings.

His major projects in the city of Trento included Fozzer house in Via Cervara, the frescoes of the Brunner house in Via Grazioli (now disappeared), the friezes that adorn the Palazzo delle Scuole Civiche on via Verdi, now the seat of the University of Sociology. In 1910 he decorated the walls of the art deco Eden cinema, located in Piazza Silvio Pellico, which has since been demolished. [cxxx] [cxxxi]

His activities during World War I appear to have been recorded incorrectly in some sources. Although Nicoletti and Weber both say he was drafted in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I, I believe this is an error, as his name does not appear in the online database of men enlisted in the military.[cxxxii] Moreover, Nicoletti tells us that he was held at Katzenau (near Linz) in 1915,[cxxxiii] which was not a POW camp but, rather, an internment camp for civilians suspected as ‘irredentists’ (i.e., pro-Italy), and thus considered enemies of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[cxxxiv] During his internment, Gustavo decorated the church at the camp.[cxxxv] Later, from 1916-1918, he was moved to Benešov (today part of Czechia), and was held at the Company of Political Suspects, [cxxxvi] where he again kept himself busy by painting the meeting room for officers.

With the defeat of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, Gustavo was no longer a political prisoner. He returned to the city of Trento, where he continued to work on commissioned projects. During this period, he painted a Madonna on the door of Casa Cappelleti on Via Grazioli, and frescoes at the halls of the regional governor on Via Grazioli.

On 12 July 1920, he passed away in Trento at the young age of 36. He had never married.

Giovanna Borzaga – Storyteller and Poetess

Born in Trento in 1931, we meet the prolific author, storyteller and poetess Giovanna Borzaga.[cxxxvii]

From the beginning, Giovanna was immersed in an environment full of educated, articulate, and artistic people. Her father was the Trento-based lawyer, Eduino Borzaga, the youngest brother of painter Gustavo Borzaga. Her mother, Francesca Zanini, was the elder sister of the renowned painter and architect, Gigiotti Zanini (1949-1967).[cxxxviii] Giovanna even wrote a biography of her uncle Gigiotti’s life.[cxxxix]

About her life and work, we read this on the back cover of a republication of her 1971 book Leggende del Trentino:

‘Giovanna Borzaga (1931-1998), journalist, collaborator at RAI [Radiotelevisione italiana], poetess, author of books for children and adults, as well as theatrical texts, passionate scholar of local culture and traditions, represented for years the ‘critical conscience and regret’ of a Trentino which exists no more, but remained in the consciousness and memory of many.’[cxl]

Her passion for a ‘Trentino which exists no more’ refers to her commitment to the preservation and retelling of Trentino folk tales and legends, drawn from the rich ‘pagan’ culture of rural Trentino[cxli], in which the natural world and the mystical are inextricably intertwined. Alongside ‘fairy tale’ characters like kings, princesses and knights, these tales contain ‘magical characters of the valleys and forests,’ including dragons, witches, wood elves and gnomes. Her writing also illustrates her clearly defined ecological perspective. Her book 3-volume series Clausilia e Moscardino is even subtitled fiaba ecologica (an ecological fable).

Below is a partial bibliography of her published works:

- Leggende del Trentino. Magici personaggi di valli e boschi

- Come vivevamo noi trentini

- Leggende dei castelli del Trentino

- Clausilia e Moscardino: fiaba ecologica (3 volumes)

- La civiltà dei minatori tirolesi

- Nel bosco verde

- Nano Pen

- Nella valle di Genova: romanzo

- I teschi d’avorio ed altri racconti trentini

- Noi Fantasmi

- La ferrovia della Valsugana: da spazzacamini ad Eisenbahner

In addition to writing of fables, Giovanna was one of a handful of poets and playwrights who published works in vernacular (i.e., local dialect), as seen her Sta nossa tera: dramma in tre atti in dialetto Trentino, as well as El Filò: Terza Raccolta Di Poesie Dialettali Trentine, and other works in which she was a contributing author.

Giovanna passed away in Trento in 1998, at the age of 67.

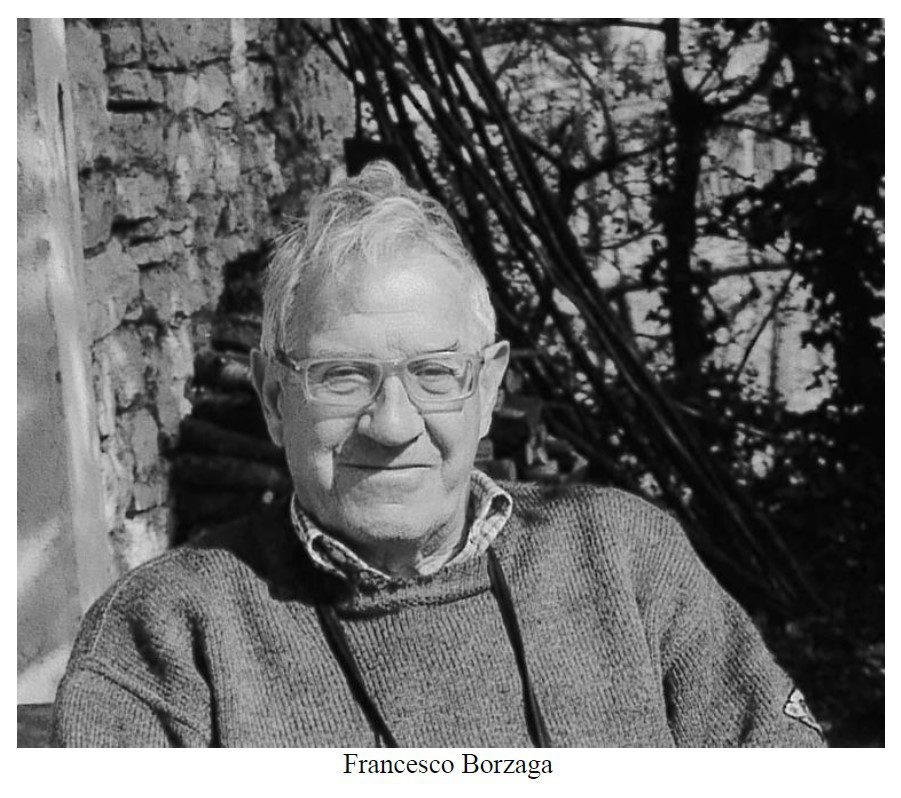

Francesco Borzaga – Environmentalist

Born in the city of Trento on 15 September 1934 (and still alive as of this writing), Francesco Borzaga is the younger brother of author Giovanna Borzaga, whom we just discussed. Like his sister, Francesco also developed a profound respect for the natural world at an early age. But where his sister used the medium of fiction to express this respect, Francesco became one of Trentino’s most distinguished environmentalists.

After graduating in Law in Bologna in 1958, Francesco working briefly at his father Eduino’s law firm, but soon found himself entering public debates on the issues of the protection of nature, and the heritage of Trentino’s historical-artistic-landscape.[cxlii] Soon, the young Francesco choose to shift his direction so he could devote his energy to the protection of the natural environment – a service which has continued to embrace for more than 60 years.[cxliii]

Early in his career, he collaborated with the Movimento Italiano Protezione della Natura (Italian Nature Protection Movement), and with the Pro Cultura and Italia Nostra association, where he served as Secretary of the Trento section until 1970. In 1968 he founded the Trentino-Alto Adige Delegation of the WWF-World Nature Fund – with the main purpose of supporting bear protection initiatives– where he served as President until 2010. [cxliv]

In 1968, he met environmental activist Donatella Lenzi, whom he would later marry in 1977. Throughout the decades, Donatella has participated in and supported her husband’s environmental activities. Since retiring, she has also become a painter. [cxlv]

In 2018, his extensive collection of writings on environmentalism and urban planning, spanning six decades from the 1950s to the present era, along with hundreds of letters, press releases and press reviews, were compiled into an archive for the benefit, education and inspiration of future environmentalists. A full inventory of the archives can be found online in the publication Francesco Borzaga. Inventario dell’archivio (1942 – 2017).[cxlvi]

Fr. Mario Borzaga – Martyr of Laos

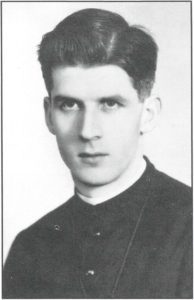

Born in the suburbs of the city of Trento on 27 August 1932, Mario Borzaga was the third of four children of Costante Borzaga of Cavareno and Ida Conci (I believe she was from Cogolo, Trento).

Drawn to the priesthood from an early age, he began his studies at the seminar in 1948.[cxlvii] Responding to a powerful an inner calling to become a missionary, he departed his homeland become a member of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate on 7 November 1952.[cxlviii] [cxlix] He was ordained on the 24 February 1957, performing his first Mass as a priest the following day.[cl] On 28 April 1957 he celebrated High Mass in at the Duomo di San Vigilio in Trento, while contemplating what his next mission should be. Soon after, he volunteered to be sent to Laos, where he felt he could be a better missionary ‘to the nations.’[cli] He departed for Laos in the autumn of that year with five other Oblates.[clii]

In the autumn of 1956 Fr. Mario began a diary, which he entitled Diario di un Uomo Felice (Diary of a Happy Man). The part of this diary that dealt primarily with his missionary experiences in Laos was published under that title (in Italian) in 1985. Other sections, which covered his seminary years and his decision to become a missionary priest, were later published under the title Verso la Felicità (Towards Happiness) in 1986.[cliii]

In his diary, Fr. Mario writes of his difficulties with learning basic survival skills, like fishing, recognising the sounds and tracks of animals, working with wood, fixing engines.[cliv] The threat of serious and unfamiliar illnesses was also every-present.[clv] But perhaps the most persistent challenges he writes about is feelings of loneliness and isolation due his difficulty in learning the language well enough to communicate well with the local people. It seems his fluency did improve over time, however, as he eventually became brave enough to try to learn Hmong as well as Laotian.[clvi]

In 1992, his younger sister Lucia, herself a member of the Secular Institute of Oblate Missionaries of Mary Immaculate, published a personal and emotive biography (in English) of her brother’s life, in which she sharers her own observations about her brother’s memoires:

His diary was written closely, without correction or afterthought, in the certainty that no-one would ever read it. He wrote rapidly, about what happened during the day. Between the lines there emerges his whole personality. The shyness disappears and what bursts through the quickness of his pen is his romantic soul, ecstatic before the beauty of creation, without hiding his aversion for manual labour, his pain and suffering, his moods, his preferences. And, intimately part of the community as he was, he sculpts in a few words the figure of his companions and friends, of the professors and superiors, without ever permitting himself superfluous observations and rash judgements.[clvii]

Biographer Gianpiero Petteti adds:

The days of the mission [in Laos] are meticulously recounted in his “Diary of a Happy Man”, which expresses in the title all his joy of being where he believes the Lord has called him, but between the lines he hides all the fatigue of his immersion in the new culture, of learning its language and customs, of adapting to the climate, of doing everything for everyone.

But all of these challenges were far less of a threat to his survival than the intense political turmoil that was shaking the entire nation of Laos during this period. In 1959, North Vietnam communists had occupied areas of eastern Laos. They found sympathetic supporters in the form of the Pathet Lao (AKA Lao People’s Liberation Army), which was a communist organisation in Laos, which would ultimately assume political power of the country in 1975.[clviii]

In the years that Fr. Mario was in Laos, ‘there was the ever-present threat of the Pathet-Lao; the danger of ambush lay in every mountain track.’[clix] Outbreaks of massacres to Christians and spiralling guerrilla warfare would frequently force him to go into hiding.[clx]

The details of his death is subject to some uncertainty, if not a bit of local legend.

We do know that, on 25 April 1960, Fr. Mario set out on a missionary visit to the village of Pha Xoua, accompanied by a 19-year-old catechist Thoj Xyooj Paj Lug (who also used the Christianised name Paolo Thao Shiong). The journey took them near the border of China. Sworn testimonies say the two were ambushed by guerrillas of Pathet Lao.[clxi] Some say this happened because they had lost their way to their destination, but Fr. Mario’s sister says the pair had reached their destination, administered the sick and ministered the sacraments, and then vanished on their return journey. [clxii]

Accounts by locals say the attack was initially aimed a Fr. Mario only, as he was a priest and a foreigner, and that his young Laotian companion was offered the chance to flee. However, Thoj Xyooj Paj Lug reportedly replied, ‘If you kill him, you kill me too. If he dies, I will die’ and he was indeed killed along with his mentor. [clxiii] [clxiv] Some sources say their remains were tossed into a pit, but they were never officially identified.

Fr. Mario Borzaga and Thoj Xyooj Paj Lug are among 17 priests and laymen venerated as the ‘Martyrs of Laos’, all of whom were killed between 1954-1970 during a time of anti-Christian sentiment. In 2015, Pope Francis officially approved their ‘beatification’, [clxv]with their beatification ceremony taking place on 11 December 2016. [clxvi]

Mario Borzaga was only 27 years old.

Frank Borzage – Hollywood Film Director

At a global level, perhaps the most famous Borzaga was Hollywood film director Frank Borzage (at some point after immigration, the family changed the spelling of their surname).

Frank was one of at least 10 children of Francesco Luigi Borzaga (but known as ‘Luigi’) of Ronzone and Maria Ruegg (or possibly Ruigg) of Switzerland.[clxvii] According to one biographer, Luigi Borzaga met his future wife when he was working as a stonemason in Switzerland. Like many other Trentini men, he emigrated to Hazleton, Pennsylvania in the early 1880s to work in the coal mines; Maria joined him later and the couple married in Hazelton sometime between 1882-1883.[clxviii] [clxix] After the birth of their first child, Henry Domenico, in 1885, the family moved to Salt Lake City, Utah, where all their subsequent children were born.

Frank was born in Salt Lake City on 23 April 1894.[clxx] In 1912, when he was still in his teens, he started working in Hollywood as a silent film actor. But his true passion for directing emerged quickly, and he made his directorial debut in 1915 with the film, The Pitch o’ Chance.[clxxi] His directing career continued for nearly 50 years, starting in the silent film era, and continuing until the year before his death in 1962. Wikipedia has attributed a whopping 113 film titles to him (although a few of the earlier ones were actually films he acted in, not directed), of which about 45 were sound pictures.[clxxii]

Having already made a breakthrough success with his silent film Humoresque in 1920,[clxxiii] Frank gained widespread critical acclaim with his 1927 film 7th Heaven (again, a silent film), for which he won the first ever Academy Award for best director of a dramatic film.[clxxiv] Shifting then into the new technology of ‘talkies’, his next major success was the Bad Girl (1931), for which he again won the Oscar for best director.[clxxv]

The following year, in 1932, he made what is probably his most famous film, A Farewell to Arms, based on the novel by Ernest Hemingway. Despite powerful performances from box office favourites Gary Cooper and Helen Hayes, it is said that Hemingway was ‘grandly contemptuous’[clxxvi] of Borzage’s treatment of his work when the film came out, and the New York Times critic panned it brutally. And although it was nominated for four Academy Awards – including Best Picture and Best Art Direction (but NOT Best Director) – it won only for its cinematography and sound recording.

Happily, later generations have seen the film through more receptive and appreciative eyes. Dan Callahan of Slant Magazine (2006) says, ‘time has been kind to the film’ adding that it ‘launders out’ Hemingway’s dry pessimism, and replaces it with ‘a testament to the eternal love between a couple.’[clxxvii] Writing in 2014, London critic Tom Huddleston calls it ‘remarkable film’, and adds (with typical British sarcasm):

‘Ernest Hemingway was scornful of this rich, romantic 1932 adaptation of his semi-autobiographical novel set in Italy during WWI.

Luckily, he was a better author than he was a movie critic.’[clxxviii]

It would be beyond the parameters of the present article to discuss more about Frank Borzage’s truly impressive catalogue of films. For those interested in reading more about his life and work, you might wish to check out the book Frank Borzage: The life and films of a Hollywood Romantic by Hervé Dumont.[clxxix]

At least three of Frank’s brothers were also active in the Hollywood film industry. His brother Lew[clxxx] worked as Frank’s assistant director for several years/ His brothers William[clxxxi] and Danny[clxxxii] were both actors. He married actress Lorena Rogers in 1916; after their divorce, he married stage manager and script writer Edna Stillwell in 1945.[clxxxiii] [clxxxiv]

Towards the end of his life, Frank received many awards in recognition of his prolific and significant contribution to the film industry. In 1955 and 1957, he received The George Eastman Award, for distinguished contribution to the art of film. On 8 February 1960, he was given motion pictures star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (located at 6300 Hollywood Blvd).[clxxxv] That same year, he was received the D. W. Griffith Award.[clxxxvi]

Frank Borzage passed away in Los Angeles on 19 June 1962.[clxxxvii]

He was the 8X great-grandson of patriarch Simone Borzaga ‘senior’, notary of Cavareno.

Conclusion

In this report, we discussed the Tuenno origins of the Borzaga family, and their arrival in Cavareno. We looked at the early generations, with specific detail given to the two patriarchs, Giovanni and Simone. We looked at the many generations of Borzaga notaries and their noble titles. We looked at how the Borzaga spread to other parts of Trentino, and how all of these lines could ultimately be traced back to the patriarch Simone Borzaga ‘senior’, sixteenth century notary of Cavareno. And, finally, we looked at the lives and contributions of five distinguished Borzaga of the 20th century.

The Borzaga continue to flourish in the province of Trento today, with the majority still living in and around Cavareno (including Ronzone and Sarnonico), with the next highest numbers in Trento and the Romeno area (Amblar, Don), respectively. Aside from these, we also find a few families in Ton, Roverè della Luna, Baselga di Pinè, Fondo and Rovereto.[clxxxviii] While I have not researched these last few families, it seems probably that they, like the others, are descended from patriarch Simone Borzaga ‘senior’, the Cavareno notary from the late 1500s.

On that same website, we also find there are a dozen Borzaga families currently living in the province of Bolzano (South Tyrol), with the largest numbers appearing in Merano and the city of Bolzano. Cognomix also shows five Borzaga families currently living in in other regions of Italy: two in Vicenza in Veneto, one in Como in Lombardia, one in Siena in Toscana, and one in Rome in Lazio.[clxxxix] It would certainly be interesting to discover if and how all of these non-Trentino families are connected to the Borzaga of Cavareno.

I hope you found this report to be interesting and informative, especially if you have Borzaga ancestors. In researching this family, I have constructed a ‘Borzaga Master Tree’ with nearly 800 people whose births span nearly 500 years, from 1485 to 1952.[cxc]

If you are seeking help researching your Borzaga family, or if you have any additional information about the Borzaga that would make a good addition to my Borzaga Master Tree, please do not hesitate to contact me at https://trentinogenealogy.com/contact.

If you enjoyed this article, you can help support my research by purchasing it as a 37-page downloadable, printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, charts, footnotes and resource list. Price: $3.75 USD.

CLICK HERE to buy this article in the ‘Digital Shop’, where you can also browse for other genealogy articles.

This article and others on this blog are ‘working drafts’ of research for my ‘in progress’ books entitled The Birth of Your Surname: The Origins, Evolution and Genealogy of 15 Ancient Trentino Families (although it might end up being more like 20 families), as well as a multi-volume set covering many hundreds of surnames called ‘Guide to Trentino Surnames for Genealogists and Family Historians. It will take me a few more years to complete these book projects, but I am offering these PDF eBooks while they are still in progress.

Until next time!

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

8 August 2022

P.S. I am currently taking client bookings for November 2022 and beyond. If you would like to book a time to discuss having me do research for you, I invite you to read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, we can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://trentinogenealogy.com/my-tree/

ENDNOTES

[i] ANZILOTTI, Giulia Mastrelli. 2003. Toponomastica Trentina: i nomi delle località abitate. Trento: Provincia autonomia di Trento, Servizio Benni librari e archistici, page 321. The original image is greyscale; I have highlighted Cavareno in yellow using Photoshop.

[ii] ENDRIZZI, Cristoforo. 1967. Cavareno: spunti di paesaggio di storia e di vita, page 18.

[iii] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino. Trento: Società Iniziative Editoriali (S.R.L.), page 53.

[iv] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino. Trento: Società Iniziative Editoriali (S.R.L.), page 53.

[v] Provincia Autonoma di Trento. ‘Compravendita’, 24 August 1501, Pellizzano. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1008967. Accessed 10 July 2022.

[vi] The Pellizzano baptismal records start in 1626, marriages in 1653, and death records in 1664. As of this writing, I was only able to check the indexes for each.

[vii] Provincia Autonoma di Trento. ‘Consegna di dote e assicurazione di dote’, 22 November 1595, Condino. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1141567. Accessed 10 July 2022.

[viii] STENICO, P. Remo. 2000. Sacerdoti della Diocesi di Trento dalla sua Esistenza Fino all’Anno 2000. Indice Onomastico, page 69.

[ix]CASETTI, Albino (dottore). 1951. Guida Storico – Archivistica del Trento. Trento: Tipografia Editrice Temi (S.R.L.), page 249-254. Due to this damage, the registers for Condino begin in 1919, although archivist Albino Casetti says there are some copies of 19th century baptismal and marriage records.

[x] LEONARDI, Enrico. 1955. Tuenno nelle sue Memorie. Trento: Arti Grafiche Saturnia, page 39-40.

[xi] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 60.

[xii] ODORIZZI, Paolo. ‘Genealogia famiglie di Tuenno (e nobili di Tuenetto)’. Annotated spreadsheet at: http://www.dermulo.it/DermuloStory/PaoloOdorizzi/Genealogia%20famiglie%20di%20Tuenno%20(e%20nobili%20di%20Tuenetto).xlsx. Accessed 12 July 2022 from ‘Dermulo: Storia di un piccolo paese’. http://dermulo.it.

[xiii] LEONARDI, Enrico. 1955. Tuenno nelle sue Memorie. Trento: Arti Grafiche Saturnia, page 39.

[xiv] ENDRIZZI, Cristoforo. 1967. Cavareno: spunti di paesaggio di storia e di vita, page 26.

[xv] ODORIZZI, Paolo. ‘Genealogia famiglie di Tuenno (e nobili di Tuenetto)’.

[xvi] ODORIZZI, Paolo. 2018. La Val Di Non E I Suoi Misteri – Volume I, page 305. PDF version downloaded 20 February 2022 from https://www.academia.edu/38068122/1_LA_VAL_DI_NON_E_I_SUOI_MISTERI_VOLUME_I_Aggiornamento_dicembre_2018. Odorizzi discusses many aspects of the Borzaga genealogy throughout the book, but his chart on ‘Genealogia famiglie di Tuenno (e nobili di Tuenetto)’ provides an easy visual summary of his conclusions.

[xvii] ODORIZZI, Paolo. ‘Genealogia famiglie di Tuenno (e nobili di Tuenetto)’.

[xviii] STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 76. Stenico only lists him as ‘Bartolomeo Borzaga of Tuenno’ but he does not say he was the son of Benvenuto. On the same page, he also mentions lists Baldassare Borzaga of Tuenno as the son of Antonio.

[xix] ODORIZZI, Paolo. 2018. La Val Di Non E I Suoi Misteri, Volume I. PDF version downloaded 20 February 2022 from https://www.academia.edu/38068122/1_LA_VAL_DI_NON_E_I_SUOI_MISTERI_VOLUME_I_Aggiornamento_dicembre_2018, page 295.

[xx] ODORIZZI, Paolo. 2018. La Val Di Non E I Suoi Misteri, Volume I, pages 295, 305 and others.

[xxi] ODORIZZI, Paolo. ‘Genealogia famiglie di Tuenno (e nobili di Tuenetto)’.

[xxii] LEONARDI, Enrico. 1955. Tuenno nelle sue Memorie. Trento: Arti Grafiche Saturnia, page 39.

[xxiii] ODORIZZI, Paolo. ‘Genealogia famiglie di Tuenno (e nobili di Tuenetto)’.

[xxiv] ODORIZZI, Paolo. ‘Genealogia famiglie di Tuenno (e nobili di Tuenetto)’.

[xxv] AUSSERER, Carl. 1985. Le Famiglie Nobili Nelle Valli del Noce: Rapporti con i Vescovi e con i Principi Castelli, rocche e residenze nobili Organizzazione, privilegi, diritti; I Nobili rurali. Translated by Giulia Anzilotti Mastrelli from the original German work Der Adel des Nonsberges, published in 1899. Malé: Centro Studi per la Val di Sole, pages 112 and 172.

[xxvi] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 60.

[xxvii] Archivio Arsio, n. 155. 18 December 1560, in Cavareno, Giovanni, son of the late Simone Chanarz (?) sells to Romedio, son of the late Baldassare Borzaga, a plot of land in Cavareno and Campaz. This is cited by Odorizzi in his online tree.

[xxviii] The last Borzaga descendant of Giovanni I have found was Giovanni Luigi, born in Cavareno on 16 June 1778. Sarnonico parish records, baptisms, volume 7, page 74-75.

[xxix] Provincia Autonoma di Trento. ‘Locazione temporale di decima’, 27 February 1594, Sarnonico. Drafted by Simone Borzaga of Cavareno, notary by imperial authority. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1104675. Accessed 10 July 2022.

[xxx] Provincia Autonoma di Trento. ‘Costituzione di censo’, 11 May 1603, Cavareno. Drafted by notary Simone Borzaga of Cavareno. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/3568069. Accessed 10 July 2022. There are many other documents for him; I have only included the earliest and the latest I have found..

[xxxi] Provincia Autonoma di Trento. ‘Costituzione di censo con dichiarazione di obbligo’, 18 August 1599, Cavareno. Cites the name of Simone Borzaga’s wife, Chiara. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1085107. Accessed 10 July 2022.

[xxxii] Romeno parish records, marriages, volume 1, page 6-7.

[xxxiii] Sarnonico parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 180-181.

[xxxiv] Sarnonico parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 80-81.

[xxxv] Sarnonico parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 118-119.

[xxxvi] Provincia Autonoma di Trento. ‘Costituzione di censo’, 25 April 1625, Sarnonico. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1089297. Accessed 10 July 2022.

[xxxvii] Nicolò Borzaga, son of Giovanni, was born 28 January 1588. Sarnonico parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 26-27. No mother’s name is mentioned in the record.

[xxxviii] TIROLER LANDESMUSEEN. Tyrolean Coats of Arms. Landing page: http://wappen.tiroler-landesmuseen.at/login.php. Borzaga stemma accessed 10 July 2022 from http://wappen.tiroler-landesmuseen.at/index34a.php?id=&do=&wappen_id=4062&sb=borzaga&sw=&st=&so=&str=&tr=99.

[xxxix] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine, page 331.

[xl] ENDRIZZI, Cristoforo. 1967. Cavareno: spunti di paesaggio di storia e di vita, page 26.

[xli] LEONARDI, Enrico. 1955. Tuenno nelle sue Memorie. Trento: Arti Grafiche Saturnia, page 40.

[xlii] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine, page 60. They specifically say the for men were brothers. They also say it was Count Alessandrini who awarded the stemma in 1626, but Enrico Leonardi (Tuenno nelle sue Memorie, page 40) says it was the Prince-Bishop, who was confirming the earlier award.

[xliii] GIACOMONI, Fabio. 1991. Carte di Regola e Statuti delle Comunità Rurali Trentine. 3 volume set. Milano: Edizioni Universitarie Jaca, volume 2, page 532; 549.

[xliv] Sarnonico parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 2-3.

[xlv] Sarnonico parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 156-157. Antonio also had at least one daughter, but while females could INHERIT their father’s noble titles and privileges, they could not pass these privileges onto their children.

[xlvi] Romedio was born 7 December 1589. Sarnonico parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 38-39.

[xlvii] STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 76. One of these four is an Antonio Borzaga, but I am positive Stenico has combined citations from two different Antonios, one who was the grandfather of the other.

[xlviii] Provincia Autonoma di Trento. ‘Costituzione di censo’, 19 December 1602, Castelfondo. Drafted by notary Antonio Borzaga of Cavareno. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/3568044. Accessed 10 July 2022.

[xlix] Provincia Autonoma di Trento. ‘Compravendita’, 20 October 1635, Sarnonico. Land sale agreement drafted by notary Antonio Borzaga of Cavareno. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/1089455. Accessed 10 July 2022. Again, there are numerous surviving documents written by him in between these dates; I have cited only the earliest and the latest of those on the Provincia Autonoma di Trento website.

[l] GIACOMONI, Fabio. 1991. Carte di Regola e Statuti delle Comunità Rurali Trentine. 3 volume set. Milano: Edizioni Universitarie Jaca, volume 2, page 532; 549.

[li] Sarnonico parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 156-157.

[lii] Sarnonico parish records, baptisms, volume 3, page 120-121.

[liii] Sarnonico parish records, marriages, volume 2, page 165-166. 28 April 1667. Adamo, son of the late Michele Zogmaister of Ruffré’ married Barbara Borzaga, daughter of ‘spectabilis’ Simone Borzaga (of Cavareno).

[liv] Provincia Autonoma di Trento. ‘Costituzione di censo’, 24 May 1627, Seio. Drafted by notary Simone Borzaga of Cavareno. Archivi Storici del Trentino, https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/51172. Accessed 10 July 2022.