Origins and history of the early Corradi of Val Giudicarie, including Daone and Stenico. By genealogist Lynn Serafinn from Trentino Genealogy.

Want to keep this article to read offline? You can purchase it as an 18-page printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, charts, footnotes and resource list.

Price: $1.99 USD.

Available in Letter size or A4 size.

Introduction

Variants: Coradi; Coraddi; Corraddi; de Corradi

Corradi is a patronymic surname is derived from the male personal name ‘Corrado’, which some linguists believe is a variant of the Germanic name ‘Conrad’, with the meaning ‘audacious in the assembly’[1] or ‘bold advisor’.[2]

Nearly 80% of the estimated 3623 Corradi families in present-day Italy live in the north, with the greatest presence by far Emilia-Romagna (about 34%).[3] Although fewer than 4% of all Corradi in present-day Italy are believed to be living in Trentino today, the surname has a long history in the province, dating back to at least the 1400s. We find, for example, a priest from Borgo Valsugana named Paolo Corradi, whose name appears in a document from 1486.[4] A bit later, we find a Corradi family who are in the list of Bishopric nobility of Livo in 1529.[5]

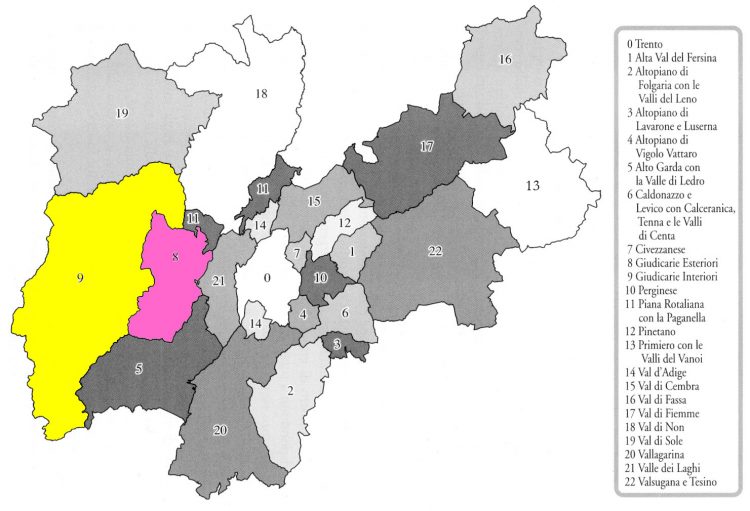

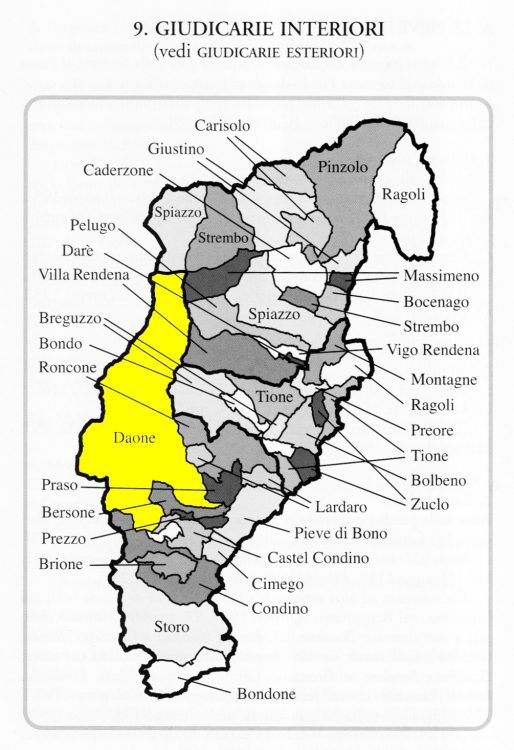

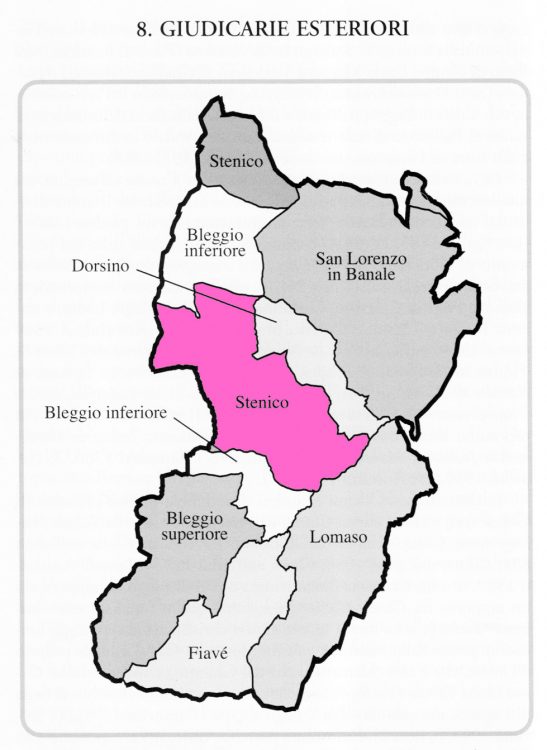

While, for many centuries, there have been significant numbers of Corradi in the southeastern part of the province (Lavarone, Pergine, Valsugana), the focus of this article will be the Corradi of Val Giudicarie, more specifically in Daone (Giudicarie Interiore, highlighted in yellow) and Stenico (Giudicarie Esteriore, highlight in pink).[6]

Corradi of Daone: The Challenges of Constructing a History

The curate parish of Daone in Val Giudicarie Interiore[7] dates back many centuries, but sadly all of its early parish registers were destroyed in World War I, rendering it impossible to do any genealogical research there. How fortunate I felt, therefore, to stumble upon an interesting article written by O. Cristoforetti nearly 100 years ago[8] about a Corradi of Daone, whose name has become part of their folkloric history. Unfortunately, later historians have pointed out many errors in Cristoforetti’s story, which cites no sources for its information, and is likely drawn solely from local legend.

Oral history everywhere is prone to historical inaccuracies (if not full-blown fiction). Nonetheless, traditional stories can give us insight into the values and perspectives of the society from which they came. For that reason, I would like to share Cristoforetti’s version of this local legend, after which I will attempt to separate the colourful fiction from the documented facts.

Folktale: Corradi and the Dowry for the Maidens of Daone

Writing in 1926, Cristoforetti tells us the story of a young man named Corradi (he does not tell us his first name) who lived in Daone sometime in the 1400s. This Corradi was an extremely poor man, but he was nonetheless very courageous and daring, with an insatiable desire to travel the world in search of adventure and fortune. He was also apparently very charming, as he seems to have been the heartthrob of the unmarried maidens of Daone. As the story goes, these young ladies were so fond of the young man, that wanted to do something to help him achieve his aspirations. Although very poor themselves, the maidens worked together to assemble a very modest ‘trousseau’ (corredo), containing sufficient supplies to make a long journey, and meet his primary needs along the way.

Equipped with his corredo, the young Corradi bid farewell to his generous benefactrices and started on his quest, his heart full of dreams, hope and gratitude. Travelling the mountain roads, he first ventured south, following the course of the River Chiese. Then, taking Passo Tonale through the glacial terrain around Mount Adamello, he arrived in Valcamonica in Lombardia. After wandered through the province of Brescia and Verona, he headed eastward to Veneto, ultimately arriving in the city of Venice. Here, he decided to stay, as it was surely the perfect place to make his fortune.

In Venice, Cristoforetti tells us, Corradi applied to become an apprentice for one of the famous glassmakers of Murano. Finding the young man to be both good-natured and intelligent, the Master glassmaker accepted him, which provided Corradi with both lodging and a steady income. The young apprentice quickly distinguished himself for his careful and delicate work, which earned him the esteem and trust of the Master glassmaker, who would assign him more and more paid commissions.

Eventually, Corradi’s enterprising skills and personal rapport with tradesmen, enabled him to rise from craftsman to merchant, selling goods that had come into the Serenissima (a nickname for medieval Venice) via the legendary ‘Silk Road’ of the East. And so, within a very short span of time, the once-impoverished Corradi became a very wealthy man.

But Corradi never forgot his difficult past, nor how the kind maidens of Daone – who were surely still living in poverty – had so selflessly come together to help him achieve his dreams. Full of gratitude, he fervently wanted to do something to repay them for their kindness.

So, Corradi entrusted a considerable fortune to the comune of Daone, for the purpose of providing dowries to 12 young women who were preparing to marry. This wasn’t a ‘one off’ gift, but a trust that was to be granted every year in perpetuity. The amount gifted to each bride, Cristoforetti tells us, was equivalent to 300 Italian lire when he was writing in 1926, which is roughly $327 USD (or £255 GBP) today). To qualify for this gift, the bride would need to be native to Daone and marrying in Daone, but it didn’t matter if her husband was from a different place, or if the couple decided to live somewhere else after marriage. If the number of brides in a given year exceeded 12, then the poorest of them were chosen to receive the dowry. If fewer than 12 marriages took place in a particular year (which was not uncommon),[9] the capital would accrue interest, and the funds for the dowries would continually increase.

Cristoforetti tells us that eight new brides in Daone had already received a gift dowry of 300 lire that year (1926), thanks to this Corradi who lived some 500 years before them. I don’t know if the trust is still in operation today, as the tradition of having a dowry has declined since the mid-20th century.

We are also told that Corradi’s generosity was not limited to his endowment for the maidens of Daone. Cristoforetti claims he also donated a grand silver chandelier to hang over the altar of the parish church, as wells as two ‘pale’ (oil paintings on wood rather than canvas), made by Palma the Younger (Palma ‘il Giovane’): one of San Bartolomeo, and one of San Lorenzo The larger and grander of the two was that of San Bartolomeo; as he was the patron saint of the church, this pala was placed behind the main altar. The other pala of San Lorenzo was placed by the side altar.

During World War I, the residents of Daone were evacuated to Braunau, because their village was in a dangerous warzone. The parroco of the church asked a friend of his, an Austrian official of Jewish origin, who was an art lover, to keep both of these artworks at his home until the war was over. Sadly, only the pala of San Lorenzo found its way back to the church. Cristoforetti doesn’t offer an opinion of what happened to the grand painting of San Bartolomeo.

Corradi in Venice: Fact Versus Fiction

Seventy years after Cristoforetti’s publication, author Sergio Giovannini wrote a substantial article on the history and art of the church of San Bartolomeo in Daone.[10] The author discusses the two paintings of that were attributed to Palma the Younger, telling us that the one (of San Bartolomeo) that had hung over the altar was stolen during the war.

He explains that the appearance of such a notable, valuable, and high-quality Venetian work in a little, out-of-the-way, mountain church in Valle de Chiese can only be understood when we consider the relations between Valle del Chiese and the city of Venice during the 1600s-1700s. For centuries, this part of the Giudicarie, which was at the extreme southwest of the Episcopal Principality of Trento, shared a border with the Republic of Venice, whose dominion extended into the lands of Lombardia, up to Brescia and Bergamo.

Thus, the people of the southern Giudicarie benefitted from direct commercial rapport with the Serenissima, and ‘not just a few’ of them found lucrative work opportunities in Venice in handicraft manufacturing (silk, glass, metalwork, etc.) and shipbuilding at Venice’s famed ‘Arsenal’. The more enterprising of these immigrants often expanded into commerce. Thus, Giovannini says, ‘from the city on the lagoon, there were not infrequent shipments of works of art – sometimes prestigious – to the southwestern Trentino churches,’ including paintings, statues, sculptures, and precious metalwork (silver and gold). ‘The conspicuous presence of Venetian works of art in the churches of southwestern Trentino,’ he says, ‘is therefore explained by the wealth, generosity, and religiosity of the emigrants (from Trentino) to Venice, who remembered their churches of origin, and frequently commissioned works of art to embellish them.’

Thus, the folktale about Corradi has some foundation in truth: we know that many men from southwestern Giudicarie found their fortune in Venice, and some of these men gifted precious Venetian artwork to their native parish churches.

But beyond that, the rest of Cristoforetti’s rendering of the story does not appear to hold up against historical evidence. Quoting art historian Ezio Chini, Giovannini tells us that the previously unnamed ‘Corradi’ was actually Corrado, son of Angelo Corradi, who migrated from Daone to Venice where he became a wine merchant.’ Apparently, this Corrado is mentioned several times in surviving archival documents, one of which is his Will, which is dated 12 August 1678 (although he died much later, on 22 June 1696).

So it appears our Corradi was not from the 1400s at all, but from the 1600s. Moreover, he was actually a wine merchant, not a glassmaker (unless that is how he started his career in Venice).

But more importantly, although Corradi left many gifts to the village of Daone and to its church in his Will, there is no known documentation for the donation of the two works of art by Palma the Younger. Even if we suppose the original papers were lost during the First World War, the chronology of events doesn’t quite add up. Palma the Younger died in 1628. As these were commissioned works, it seems improbable that Corrado Corradi (who died in 1696) would have been a wealthy merchant in Venice by the year 1628. He may not even have been born yet. Giovannini, thus, concludes that these paintings were probably donated by someone from an earlier generation, whose name has since been forgotten.

What Do We Really Know about the Early Corradi of Daone?

Sadly, the answer to this question is: not a lot.

In terms of genealogy, the greatest wartime loss in Daone are its parish registers. Piecing together what scant evidence that has managed to survive, we can at least say with certainty that the surname Corradi was already present in Daone by the mid-1600s.

Aside from this, we might speculate:

- As the Corrado Corradi was a merchant (possibly of humble beginnings), and is not described as nobility, it seems unlikely that the Corradi of Daone were related to the Corradi of Stenico (the subject of the next section), whose origins can be traced to the 1100s. If these two branches were related at some point, the Daone line has to have split away much earlier than the 1600s.

- I have already mentioned that the surname Corradi is also found in greater numbers in various provinces in northern Italy. The closest of these to Daone are the provinces of Brescia and Mantova, which share a border with the southwestern Giudicarie Interiore.[11] If the Daone line is not connected to the Corradi of Stenico, perhaps their origins lie somewhere in Lombardia, or in one of the other northern regions. While I have seen no suggestion of this, and this is entirely my own speculation, we do at least know from numerous sources that there was significant movement (and commerce) to/from southwestern Trentino and parts of Lombardia in the late medieval and renaissance era.

The Noble Corradi Stenico – Origins

In sharp contrast to the Corradi of Daone, we have a substantial amount of documentation for early the Corradi of Stenico (Val Giudicarie Interiore).[12]

The Corradi of Stenico are an ancient noble line, whom many believe descended from the original Lords of Stenico.[13] One author suggests they were specifically descended from Bozone di Stenico (who ordered the building of the tower and cistern of Castel Stenico in 1163, and was deceased by 1202), or at least someone in his immediate family.[14] A document drafted nearly 500 years later (1641) declared that the family were indeed descended from the ancient Lords of Stenico, but that the family had originally come from either Merano or Bolzano in South Tyrol.[15]

Early 20th century historian Carl Ausserer believed that the patriarch from whom the Corradi derived their surname was one Corrado of Stenico, son of the late Giovanni Todeschini. He tells us that we first find this Corrado in a document from 1375, where his name is spelled ‘Chunradus’ – again very similar to the Germanic name ‘Conrad’.[16] Some years later, we find him again when he acquires various fiefs and rights of the decime (tithes) for Stenico and the surrounding area in 1390.[17] [18]

However, drawing upon the genealogical research of the notary Giorgio Aliprando Zorzi of Stenico, present-day historian Ennio Lappi ‘respectfully corrects’ Dr Ausserer, by telling us that the likely patriarch of the Corradi was alive in Stenico nearly two centuries earlier. The name of this ‘Corrado da Stenico’ appears in documents in 1208 and 1218, along with the name of his son, Bacogolo (or Bochegnolo). A few years later, we find him mentioned as the mayor (sindaco) of Stenico, when he is present at a number of trials (1220-1222). After that, in 1250, we find another Corrado of Stenico (whom Lappi presumes is the grandson of the other Corrado) cited in a document along with his brother Pellegrino.[19]

Author Carlo Alberto Onorati says they were one of the Giudicarie families who already had the title of ‘rural nobility’ before the year 1500.[20]

The Lineage of Corradi Notaries

After these early documents, we find that many of Corrado’s male descendants were notaries, as evidenced by several surviving legal documents bearing their names, which have been preserved in various archives.[21]

P. Remo Stenico has cited the names of several Corradi notaries of Stenico, often with the names of their fathers, and with the years of documents on which their names and/or signatures appear.[22]

Additionally, we also find a notary named Aldrighetto Corradi, son of ‘Antoniollo’ Corradi, recorded in a document dated 25 March 1515, preserved at the archives of Vigo Lomaso (Val Giudicarie).[23]

Weaving together all of this information, we can construct a rough chronology of Corradi notaries whose fathers have been identified in various documents.[24] The dates indicate the years where we find their signatures in surviving legal documents (i.e., when they were active in their profession).

- 1447: Antonio Corradi of Stenico, also known as ‘Antoniollo’, son of Aldrighetto (Aldrighetto was deceased by 1497).

- 1494-1547. Ser Aldrighetto Corradi, son of Antoniollo. One record says he was living in Villa in the parish of Banale in 1494. Interestingly, in a notary document drafted in Storo on 28 April 1514, Aldrighetto is called the cousin of the notary Giovanni Antonio Endrici (son of Guglielmo) of Bono in the parish of Bleggio.[25] So, perhaps his father Antoniollo married an Endrici,[26] or Guglielmo Endrici married a Corradi. He died sometime before 1552.

- 1549-1553: Agostino, son of Aldrighetto Corradi of Stenico. We will discuss him in more detail shortly.

- 1525; 1531: don (priest) Antonio Corradi, was another son of the notary Aldrighetto. He was both a priest and a notary (although I cannot yet say in which order, or if the two occupations overlapped). He was the assistant pievano of the parish of Banale in 1525,[27] but we also see his name as a notary in 1526.[28]

- 1544-1554: Giovanni Giacomo, son of the Agostino, son of Aldrighetto. Stenico says he worked in the parish of Ossana. (We also know of a priest named Giovanni Giacomo Corradi, who served as the pievano of Tavodo at least between 1595 until his death in March 1602, who may have been a close relation).[29]

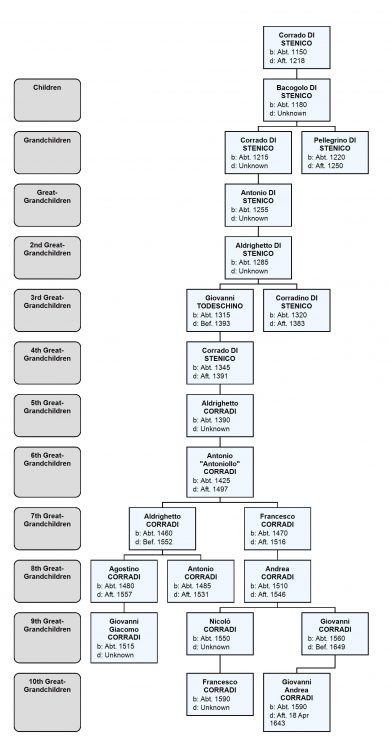

Later, we also find a notary named Giovanni Andrea (son of a Giovanni Corradi), who was active roughly between 1626-1649.[30] Note that his father was NOT the notary Giovanni Giacomo listed above. I haven’t had the opportunity to verify his ancestry yet, but 18th century notary named Giorgio Aliprando Zorzi[31] constructed a very rough (and slightly difficult to understand) family tree of the male lines of Corradi descendants up to the year 1732,[32] in which he identifies this Giovanni as a second cousin of Giovanni Giacomo. Splicing together all the documented evidence I have found with some of Zorzi’s research, we can construct a rough descendant chart from patriarch Corrado of Stenico down to some of his 10X great-grandsons, including notary Giovanni Andrea. All dates are GROSS approximations (and surely have many inaccuracies), and I have not included all of Zorzi’s entries (I would want to verify them first):

Agostino Corradi: Lieutenant of Castel Stenico

Agostino Corradi was the son of the notary Aldrighetto Corradi. Following in his father’s footsteps, he also served as a notary, and was also a jurist (giurisperito) of the curia of Stenico.[33] In 1512, he was appointed Assistant Captain (i.e., ‘Lieutenant’) of Castel Stenico, serving under Captain Giacomo of Cles, the brother of Prince-Bishop Cardinal Bernardo Cles.[34] He is also referred to as ‘Vicario’ of Stenico in a document from 1526.[35]

Ever loyal to the Prince-Bishop, he and his brother Antonio were part of the episcopal military during the rustic wars (Guerra Rustica) of 1525.[36] It is also said that Agostino was a skilled diplomat, who helped maintain calm in Stenico (and the Giudicarie in general) during the uprisings by acting as a mediator between wealthy landowners and contadini (peasant farmers).[37]

Agostino maintained his role as Lieutenant of Castel Stenico until 1541,[38] when he was elevated to the rank of Captain of both Castel Spine in Val Giudicarie and Castel Mechel in Val di Non.[39] [40]

Giovanni Andrea Corradi: Imperial Nobility

As mentioned, Giovanni Andrea Corradi (son of Giovanni) served as a notary roughly between 1626-1649. From various references, I know he and his wife Margherita had at least four children, but I have not researched them yet in detail.

In a document dated 28 September 1626, we learn that Giovanni Andrea Corradi was then serving as the Chancellor of Stenico.[41]

On 18 April 1643, Giovanni Andrea was awarded nobility of the Holy Roman Empire (S.R.I.) by Archduchess Claudia de’ Medici, who was then acting as Regent of the Austrian County of Tyrol in the name of her son Ferdinand Charles.[42]

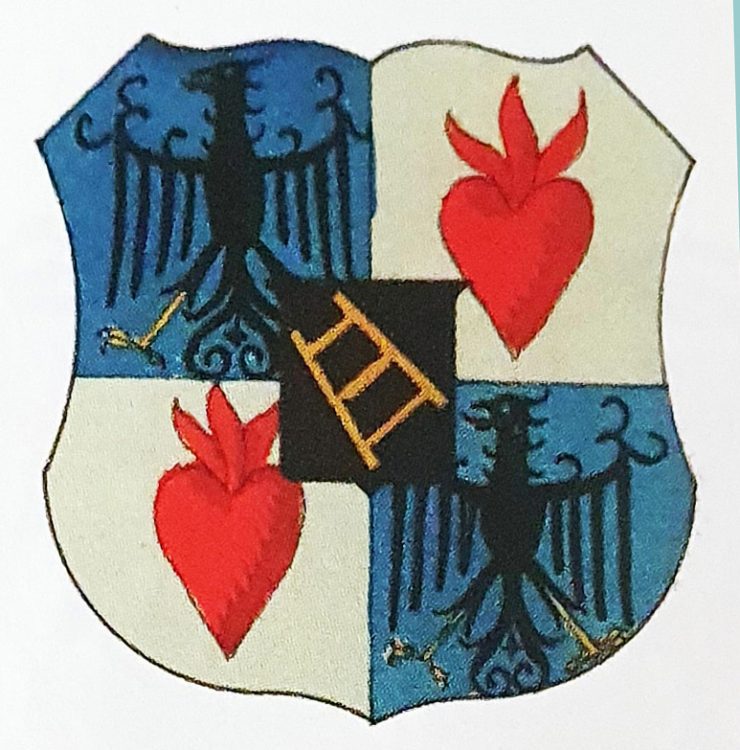

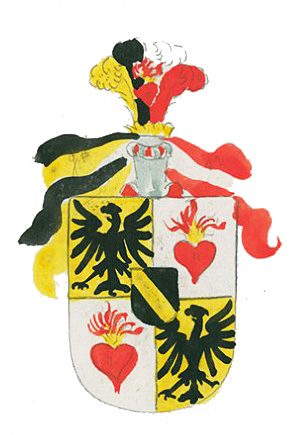

With this imperial honour, the ancient family stemma was expanded and embellished.[43] We’ll look at the evolution of the Corradi stemma next.

Evolution of the Corradi Stemma (Coats-of-Arms)

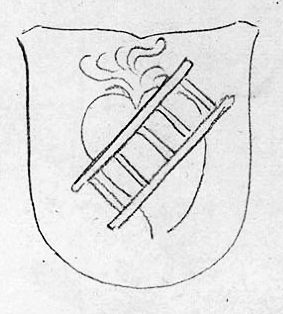

While there have been different versions of the stemma of the Corradi of Stenico over the centuries, all have been embellishments of their most ancient coat-of-arms, which depicted a golden ladder (usually drawn at an angle) against a black shield:[44]

A later version shows a red heart behind the ladder (the only image for this version I have found is in black and white). The flourish we see above the heart is supposed to be flames, symbolising fervent ardour and bravery: [45]

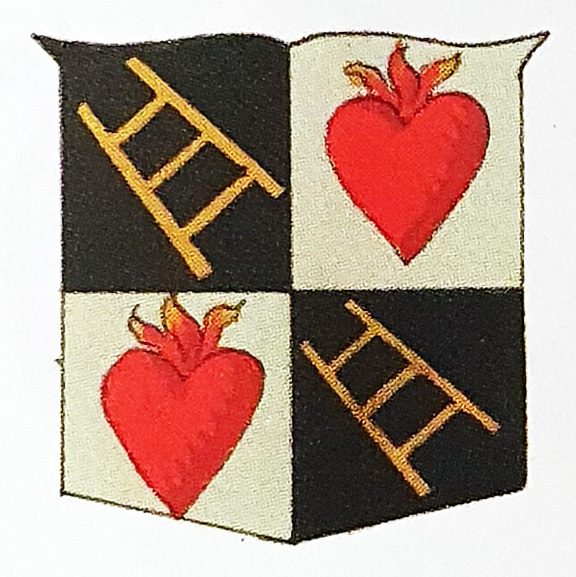

When Giovanni Andrea Corradi was granted imperial nobility in 1643, the stemma was changed once again. Now divided into four sections, we find the flaming heart in diagonally opposite quarters. I have found two variants, with different symbols in the other two quarters. The first has the ancient golden ladder:[46]

The other variant has an eagle (representing the Holy Roman Empire) in the other two quarters, with the original stemma superimposed in the middle, at the intersection of the four quadrants. Again, there is more than one variant of this layout; in this version, the eagles are drawn against a dark blue background:[47]

Later versions of this imperial stemma are more elaborate renditions of the same. Here is a drawing of one that is preserved at the Landes Museen in Innsbruck, where we see a crest above the shield, and with more intricately drawn flames coming out of the hearts. Additionally, the eagles are now on a background of gold:[48]

The Corradi of Stenico after 1650

In later centuries, we continue to find the Corradi of Stenico appearing in high-ranking positions in local government. Author Onorati[49] mentions:

- Giovanni Corradi, who was Vicario of Tione in 1686.

- Andrea Gennario Corradi, who was Lieutenant of Castel Stenico in 1721.

- Giovanni Andrea Corradi, who was Vicario of Tione from 1775-1779.

Onorati observes that, unlike many other Trentino nobility, the Corradi retained their noble rank after the Napoleonic invasions (ca. 1790-1805), and that we continue to find them listed in senior-ranking positions until the end of the 19th century.

The Corradi in Trentino from 1815 to the Present Day

Looking at the Nati in Trentino website,[50] we find over 1,013 Corradi births recorded in Trentino between the years 1815-1923, including 4 Corradi babies (presumably from Daone) in the camp of Braunau during World War 1. In addition, we find 105 births entered as ‘Coradi’, 26 as ‘Corraddi’, and 17 as ‘Coraddi’. Lastly, we find 10 births registered in Arco under the surname ‘de Corradi’, who were actually a branch of the Corradi of Stenico. Thus, altogether, at least 1,171 Corradi births were recorded in Trentino within that 109-year period.

Among these, 172 Corradi births were registered in Daone between 1875-1923, and I feel confident in saying that, had their parish registers not been destroyed, would surely find at least another 100 between 1815-1874. Towards the end of the 19th century, a pair of brothers (Bartolomeo and Angelo) moved from Daone to the parish of Santa Croce del Bleggio (still in Val Giudicarie), where it still survives today.

Although about 20% of all Corradi born in Trentino between 1815-1923 were from Stenico,[51] only a handful of Corradi live there today. Also, as mentioned above, one family group transferred from Stenico to Arco around the beginning of the twentieth century. After having sold all of the family’s ancient lands and houses in Stenico and the surrounding areas,[52] [53] some of these Arco families adopted the variant ‘de Corradi’, presumably a nod to their noble heritage. Today, only a few Corradi families remain in Arco.

Although not the focus of this report, we find the greatest numbers of Corradi in the southeastern part of the province, especially in Valsugana (Novaledo, Roncegno, Borgo), Pergine (and its related parishes), and – most prominently – in Lavarone.[54] While I have not personally researched these lines, the Corradi of Pergine are apparently descended from a Corradi man who moved there from Calceranica on Lago di Caldonazzo at the end of the 1700s.[55] It is interesting to note that the spelling variants mentioned above are used almost exclusively in the southeastern part of the province, and not among the Giudicarie families.

A trend towards urbanising can also be seen in the 19th century, as roughly 10% of Corradi born in Trentino between 1815-1923 lived in and around the city of Trento.

Closing Thoughts

The aim of this report was to discuss the origins and history of the Corradi families of Val Giudicarie, in the southwestern part of the province of Trentino.

Although we touched upon the Corradi of Daone, my greater focus has been on the Corradi of Stenico, as their well-documented lineage tack us back to the Lords of Stenico in the 12th century.

My intention was not to provide an exhaustive history, but rather to present an amalgamation of findings I have gleaned from a variety of Italian-language sources, with my own analysis of the same. In this way, to those who have Corradi ancestors, I hope I have helped to add some colour and depth to your family history.

As always, if you have well-documented information about the history these lines (or about the Corradi of south-eastern Trentino, whom I did not examine in this report), I welcome your comments and communication.

I hope you enjoyed this brief history of the Corradi of Val Giudicarie. If you would like to keep this article to read offline, you can purchase it as an 18-page printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, charts, footnotes and resource list.

Price: $1.99 USD.

Available in Letter size or A4 size.

If you have any comments or questions, or if you are seeking help researching your Trentino family, please feel free to contact me at https://trentinogenealogy.com/contact.

Until next time!

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

17 July 2023

P.S. I am currently taking client bookings for September 2023 and beyond. (I am also hoping to plan a research trip to Trento in the autumn, but I haven’t set anything up yet). If you would like to book a time to discuss having me do research for you, I invite you to read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, we can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry

(please note that the online version is VERY out of date, as I have been working on it offline for the past 5 years):

https://trentinogenealogy.com/my-tree/

NOTES

[1] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino. Trento: Società Iniziative Editoriali (S.R.L.), page 99.

[2] BEBER, Lino; ZAMPEDRI, Marzio. 2010. Le Genealogie Perginesi Rivisitate. Storia delle famiglie e documentazione fotografica. Pergine (TN): Parrocchia di Pergine Valsugana, Archivio decanale, page 246.

[3] COGNOMIX. ‘Mappe dei Cognomi Italiani: Corradi’. Accessed 22 June 2023 at https://www.cognomix.it/mappe-dei-cognomi-italiani/CORRADI/TRENTINO-ALTO-ADIGE/TRENTO

[4] STENICO, P. Remo. 2000. Sacerdoti della Diocesi di Trento dalla sua Esistenza Fino all’Anno 2000, page 114.

[5] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 99. The authors point out that the Livo family do not appear to be connected to the Corradi of Stenico.

[6] ANZILOTTI, Giulia Mastrelli. 2003. Toponomastica Trentina: i nomi delle località abitate. Trento: Provincia autonomia di Trento, Servizio Benni librari e archistici. Original map on page 10 is in greyscale; I have highlighted the relevant valleys in Photoshop.

[7] Map of Val Giudicarie Interiore from ANZILOTTI, Giulia Mastrelli. 2003. Toponomastica Trentina: i nomi delle località abitate. Trento: Provincia autonomia di Trento, Servizio Benni librari e archistici. Original map on page 187 is in greyscale; I have highlighted Daone in Photoshop.

[8] CRISTOFORETTI, O. 1926. ‘Archivio Folcloristico: La dote per le nubili di Daone’. Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, Anno VII (1926), Serie I, Fascicolo I, page 295-296. In the following paragraphs, I am paraphrasing Cristoforetti’s story based on my own translation from the original Italian.

[9] Daone is very tiny, it was not uncommon to have a year when fewer than 12 women married. Also, Cristoforetti says, during wartime, there were some years when no marriages took place at all.

[10] GIOVANNINI, Sergio. 1996. ‘La Chiesa di S. Bartolomeo a Daone’. Judicaria, n. 33 (December 1996), page 31-48. Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. All references I have made to this article appear on page 43. Again, the wording is my paraphrasing of my own translation from the original Italian.

[11] COGNOMIX. ‘Corradi’. Accessed 17 June 2023 from https://www.cognomix.it/mappe-dei-cognomi-italiani/CORRADI/LOMBARDIA

[12] Map of Val Giudicarie Interiore from ANZILOTTI, Giulia Mastrelli. 2003. Toponomastica Trentina: i nomi delle località abitate. Trento: Provincia autonomia di Trento, Servizio Benni librari e archistici. Original map on page 165 is in greyscale; I have highlighted Stenico in Photoshop.

[13] ONORATI, Carlo Alberto. 1993. ‘Le famiglie nobili e notabili delle Giudicarie Esteriori’. Judicaria, n. 22 (January-April 1993). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. Page 29-30.

[14] AUSSERER, Carl (Dr). 1911. Il Castello di Stenico nelle Giudicarie, coi suoi Signori e Capitani. Italian version translated (from the original German) by Giulia Mondini, widow of Martinelli. Trento: Scotoni e Vitti Ed. Originally published in supplement III of magazine Pro Cultura: Rivista bimestrale di studi trentini, page 12-13.

[15] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 99.

[16] AUSSERER, Carl (Dr). 1911. Il Castello di Stenico nelle Giudicarie, coi suoi Signori e Capitani. Italian version translated (from the original German) by Giulia Mondini, widow of Martinelli. Trento: Scotoni e Vitti Ed. Originally published in supplement III of magazine Pro Cultura: Rivista bimestrale di studi trentini, page 72-73.

[17] AUSSERER, Carl (Dr). 1911. Il Castello di Stenico nelle Giudicarie, coi suoi Signori e Capitani. Italian version translated (from the original German) by Giulia Mondini, widow of Martinelli. Trento: Scotoni e Vitti Ed. Originally published in supplement III of magazine Pro Cultura: Rivista bimestrale di studi trentini, page 72-73.

[18] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 99.

[19] LAPPI, Ennio. ‘I Corradi’. http://enniolappi.altervista.org/genealogia.html. Accessed 9 June 2023.

[20] ONORATI, Carlo Alberto. 1993. ‘Le famiglie nobili e notabili delle Giudicarie Esteriori’. Judicaria, n. 22 (January-April 1993). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. Page 16.

[21] ONORATI, Carlo Alberto. 1993. ‘Le famiglie nobili e notabili delle Giudicarie Esteriori’. Judicaria, n. 22 (January-April 1993). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. Page 29-30. The author says at least six of these are at the Archivio di Stato in Trento.

[22] STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 113-114.

[23] TOVAZZI, Giangrisostomo, OFM. 2004. L’Archivista Lomasino. Curated by Ennio Lappi and P. Remo Stenico (original text written in 1795). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. Page 82, document 40.

[24] There are a few others whose fathers are not identified in Stenico’s book. A hand-drawn tree made by 18th century notary Giorgio Aliprando Zorzi connects some of these men to specific lines, but the information in his tree would need verification.

[25] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Compromesso’. 28 April 1514, Storo. Notaio: Giovanni Antonio di Guglielmo Endrizzi da Bono (Bleggio) (SN), insieme al cugino Aldrighetto di Antoniollo di Aldrighetto Corradi da Stenico (SN). https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/5252489. Accessed 19 June 2023.

[26] The Endrici were another noble family, who were later known by the surname Cilladì.

[27] STENICO, P. Remo. 2000. Sacerdoti della Diocesi di Trento dalla sua Esistenza Fino all’Anno 2000, page 114.

[28] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Concessione’. 2 October 1526, Stenico. The document refers to Agostino as the Vicario (of Stenico) and Lieutenant of Castel Stenico. The original document was drafted in an abbreviated form by the Agostino’s father Aldrighetto Corradi of Stenico, and the full version was written by Agostino’s brother, Antonio. https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/2233613. Accessed 19 June 2023.

[29] STENICO, P. Remo. 2000. Sacerdoti della Diocesi di Trento dalla sua Esistenza Fino all’Anno 2000, page 114.

[30] STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 114. His father Giovanni was deceased by 1649.

[31] STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 352. The author cites documents drafted by Zorzi between 1695-1741.

[32] You can see Zorzi’s hand-drawn tree at LAPPI, Ennio. ‘I Corradi’. http://enniolappi.altervista.org/genealogia.html. Accessed 9 June 2023.

[33] TOVAZZI, Giangrisostomo, OFM. 2004. L’Archivista Lomasino. Curated by Ennio Lappi and P. Remo Stenico (original text written in 1795). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. Page 186, in the notes to document 75. Also page 89, in notes to document 44.

[34] AUSSERER, Carl (Dr). 1911. Il Castello di Stenico nelle Giudicarie, coi suoi Signori e Capitani. Italian version translated (from the original German) by Giulia Mondini, widow of Martinelli. Trento: Scotoni e Vitti Ed. Originally published in supplement III of magazine Pro Cultura: Rivista bimestrale di studi trentini, page 104.

[35] PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Concessione’. 2 October 1526, Stenico. The document refers to Agostino as the Vicario (of Stenico) and Lieutenant of Castel Stenico. The original document was drafted in an abbreviated form by the Agostino’s father Aldrighetto Corradi of Stenico, and the full version was written by Agostino’s brother, Antonio. https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/2233613. Accessed 19 June 2023.

[36] ONORATI, Carlo Alberto. 1993. ‘Le famiglie nobili e notabili delle Giudicarie Esteriori’. Judicaria, n. 22 (January-April 1993). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria, page 29-30. The author refers to his brother as ‘Gianantonio’, but I presume this is the same ‘Antonio’ who was a notary and later a priest.

[37] TOVAZZI, Giangrisostomo, OFM. 2004. L’Archivista Lomasino. Curated by Ennio Lappi and P. Remo Stenico (original text written in 1795). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. Page 186, in the notes to document 75. Also page 89, in notes to document 44.

[38] AUSSERER, Carl (Dr). 1911. Il Castello di Stenico nelle Giudicarie, coi suoi Signori e Capitani. Italian version translated (from the original German) by Giulia Mondini, widow of Martinelli. Trento: Scotoni e Vitti Ed. Originally published in supplement III of magazine Pro Cultura: Rivista bimestrale di studi trentini, page 104-105.

[39] TOVAZZI, Giangrisostomo, OFM. 2004. L’Archivista Lomasino. Curated by Ennio Lappi and P. Remo Stenico (original text written in 1795). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. Page 89, in notes to document 44 (Regole di Madice, 15 June 1541).

[40] CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1936. Inventari e Regesti degli Archivi Parrocchiali della Val di Sole. Volume 1: La Pieve di Ossana. Trento: Libreria Moderna Editrice A. Ardesi. Page 309, pergamena 323. ‘Agostino Corradi, captain of Castel Mechel’ cited as a witness at a legal agreement drafted in Mezzana on 19 August 1557.

[41] TOVAZZI, Giangrisostomo, OFM. 2004. L’Archivista Lomasino. Curated by Ennio Lappi and P. Remo Stenico (original text written in 1795). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. Page 228, document 127.

[42] WIKIPEDIA. ‘Claudia de’ Medici. Accessed 8 June 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claudia_de%27_Medici

[43] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 99.

[44] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 338.

[45] AUSSERER, Carl (Dr). 1911. Il Castello di Stenico nelle Giudicarie, coi suoi Signori e Capitani. Italian version translated (from the original German) by Giulia Mondini, widow of Martinelli. Trento: Scotoni e Vitti Ed. Originally published in supplement III of magazine Pro Cultura: Rivista bimestrale di studi trentini, page 73.

[46] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 338.

[47] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 338.

[48] GOLDEGG, Hugo. Coat of Arms Collection Text (Notes on noble families in Tyrol and Vorarlberg) [on this card: Coll. Goldegg. T.-A.-M. 1899] Location: Innsbruck Tiroler Matriculation Foundation (peer foundation). ‘Corradi, 1634’. Accessed 10 June 2023 from http://wappen.tiroler-landesmuseen.at/index34a.php?wappen_id=7294.

[49] ONORATI, Carlo Alberto. 1993. ‘Le famiglie nobili e notabili delle Giudicarie Esteriori’. Judicaria, n. 22 (January-April 1993). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. The article is on page 8-46, but the details about the Corradi are on page 29-30.

[50] NATI IN TRENTINO. Provincia autonomia di Trento. Database of baptisms registered within the parishes of the Archdiocese of Trento between the years 1815-1923. https://www.natitrentino.mondotrentino.net/.

[51] According to NATI IN TRENTINO, 193 Corradi (three of them spelled ‘Coradi’) were born in the parish of Stenico between 1815-1923. https://www.natitrentino.mondotrentino.net/.

[52] ONORATI, Carlo Alberto. 1993. ‘Le famiglie nobili e notabili delle Giudicarie Esteriori’. Judicaria, n. 22 (January-April 1993). Tione: Centro Studi Judicaria. The article is on page 8-46, but the details about the Corradi are on page 29-30.

[53] AUSSERER, Carl (Dr). 1911. Il Castello di Stenico nelle Giudicarie, coi suoi Signori e Capitani. Italian version translated (from the original German) by Giulia Mondini, widow of Martinelli. Trento: Scotoni e Vitti Ed. Originally published in supplement III of magazine Pro Cultura: Rivista bimestrale di studi trentini, page 73.

[54] According to the ‘Italia indettaglio’ website, there are about 57 Corradi currently living in Lavarone, and about 44 in Pergine Valsugana, as of 22 June 2023. https://italia.indettaglio.it/ita/cognomi/cognomi_trentinoaltoadige.html

[55] BEBER, Lino; ZAMPEDRI, Marzio. 2010. Le Genealogie Perginesi Rivisitate. Storia delle famiglie e documentazione fotografica. Pergine (TN): Parrocchia di Pergine Valsugana, Archivio decanale, page 246.