Genealogist Lynn Serafinn examines the valleys, villages and parishes in the Province of Trentino, and the people who lived there. Part 1 in series.

Genealogist Lynn Serafinn examines the valleys, villages and parishes in the Province of Trentino, and the people who lived there. Part 1 in series.

It seems at least once a week, whether I am speaking with a new client or a new member of our Trentino Genealogy group on Facebook, I find I myself having to explain many basics about Trentino geography and localities. But for some reason, despite the obvious need, I’ve never yet discussed the subject of geography in any detail on this website.

Now, if your immediate, involuntary response to the word ‘geography’ is to yawn, you’re not alone. For me, it conjures up recollections of my 7th grade geography class in Catholic school on Long Island, where we had to memorise all the local industries of Schenectady, New York, and so on.

YAWN indeed!

Perhaps my own avoidance of the topic was due to those images of me struggling to stay awake at the back of Sister Rose Winifred’s classroom. Or, perhaps on an unconscious level, I was also worried my readers would find it a sleepy subject, even if it is crucial to our full understanding of our ancestors’ lives.

It seems my concerns were not completely unfounded. To find out whether I was being too subjective, I recently polled our Facebook group, asking them what they thought about my writing an article series on the topic of the geography of Trentino, but with a genealogical focus.

Of the 49 people who responded:

-

- 35 said they thought it was a great idea.

- 10 said it sounded good, but they weren’t sure the topic would sustain their interest (especially if it was spread across many articles).

- 4, including some experienced researchers, said they weren’t sure (possibly because they had no idea of how I would broach the subject)

- Nobody said they thought it was a bad idea. Perhaps some were just being polite. 😉

So, while a clear majority liked the idea with some enthusiasm, I cannot ignore the fact that over a quarter of the responses expressed some doubt about the topic.

Therein lay my challenge:

How could I present the subject of the geography of Trentino in such a way that it could sustain the interest – and be useful to – beginners through advanced researchers?

I believe the key to that challenge lies in examining not just where places are on a map, but also WHO is in those places, and HOW people and places are connected.

MESSAGE TO ADVANCED RESEARCHERS: Article 1 in this series is, by necessity, going to cover some basics, which some of you with more experience and knowledge are likely to want to ‘skim’. But I promise you, as this series progresses, it will become far more detailed and specific, combining information from many different Italian resources. So, even if you want don’t read every word of this introductory article, I humbly ask that you to get a feeling for where I will be going from here. My sincere hope is that this series will ultimately become a valuable ‘go to’ reference for you and all my readers.

So, let’s begin…

The Four ‘Lenses’ of Geography

Geography is actually a multidimensional subject. It is not just about lumps and bumps on a map, but a complex set of interrelated factors. It isn’t just about where things are, but how they are divvied up, what they are called and who has ‘dominion’ over them.

Thus, in this series, I’d like to explore Trentino ‘geography’ through these different ‘lenses’:

-

- Civil, i.e. the state

- Ecclesiastical, i.e. the church

- Geographic, i.e. the land itself

- People

These lenses are inextricable intertwined. Only by considering them as a whole can we attempt to create an accurate, historical and cultural portrait of any land – and its people.

‘People’ are inevitably part of the geographic landscape. People create, respond to, adapt to and change everything within the other three lenses. Their surnames, language, customs, beliefs and behaviour cannot truly be understood in a vacuum, without the context of geography.

And none of these factors can be understood outside the dynamics of time. While changes in the lay of the land itself may not be as apparent to us (although rivers are frequently shifting their path), state and church boundaries are constantly in flux, and people have always moved from one place to another. Thus, ‘time’ is an overarching container in which these four lenses dwell and move.

Many family historians become disproportionately focused on the ‘people’ lens, often at a somewhat ‘micro’ level. That is to say, they tend to collect names, dates, and other facts about of specific families (usually their own) without giving a great deal of attention to the multidimensional context in when those people lived.

Conversely, so many ‘pure historians’ give a disproportionate amount of weight to the importance the state (governments, politics, wars, etc.), at the expense of the geographic or demographic lenses.

Both of these approaches to history can result in a somewhat myopic view, missing the richness of our ancestors’ experiences of life. Only by taking a multidimensional approach to family history can we begin to understand how people and their institutions are inevitably interdependent with the land.

CIVIL STRUCTURE: Italian Regions and Provinces

As discussed in my article Ethnicity Vs. Cultural Identity. Trentino, Tyrolean, Italian?, the province of Trentino has ‘belonged’ to many different political powers throughout the centuries. Although my discussion of ‘civil structure’ will be about Trentino within the CURRENT ‘nation’ we know as ‘Italy’ today, please understand that everything I write about Trentino is referring to the SAME place, regardless of whether it was then part of the Holy Roman Empire, Austria or Italy.

So, let’s have a look at this place called ‘Italy’ and how it is divided up at a civil/political level.

For the most part, Italy’s CIVIL structure is broken down like this:

Region –> Province –> Municipality –> Village

I say ‘for the most part’ because there are some places where provinces and comuni were replaced by other entities; but as this is the structure that applies to our current topic, we’ll stick to that as a guideline.

The Italian words for these terms are:

Regione –> Provincia –> Comune –> Frazione

In the present-day country of Italy, there are currently 20 regions, 110 provinces, nearly 8,000 comuni, and I have NO idea how many frazioni.

Region

The region under discussion in this article series is Trentino-Alto-Adige, which is highlighted in RED in the map below:

In this map, we can see easily that Trentino-Alto Adige is the northernmost region in the country. It is situated the Dolomite mountain range, part of the Alpine system.

Province

Regions generally have more than one province.

If we zoom in more closely, we can see that the region of Trentino-Alto Adige is divided into two provinces: Trentino and South Tyrol (synonymously called ‘Alto Adige’ or the ‘Province of Bolzano’):

Boundaries for the provinces have remained reasonably the stable over the past century, with some exceptions. For example, the area known as Valvestino (west of Lago del Garda) was historically part of Trentino, but was given to the province of Brescia (in the Region of Lombardia) in 1934.

Your will often see Trentino referred to as the ‘Province of Trento’ (Provincia di Trento). This can sometimes be confusing for someone unfamiliar with the area, as ‘Trento’ is also the name of the capital city. For that reason, I will always say ‘Trentino’ when referring to the province and use the word ‘Trento’ when referring to the city (unless I specify ‘Province of Trento’).

Similarly, you might see the Province of South Tyrol referred to as ‘Alto Adige’ as well as the ‘Province of Bolzano’. However, recently the shift towards its historic name of ‘South Tyrol’ has taken precedent.

Is Trentino the Same as Tyrol?

Today, it NOT technically correct to refer to Trentino as ‘Tyrol’ or ‘South Tyrol’, even though many descendants of Trentino immigrants who left the province before or shortly after it became part of Italy identified themselves as ‘Tyrolean’. I have lived in England for over 20 years, and if you say ‘South Tyrol’ to anyone here in the UK or in continental Europe, they will always assume you are referring to the South Tyrol as it appears on the map above, not Trentino. Again, cultural identity does not always match up with current political boundaries.

So, for this study, I will never refer to Trentino as Tyrol or South Tyrol, even though I know and agree that many readers might think of themselves as ‘Tyrolean’.

Comuni

As a comune (plural comuni) is a local administrative entity, their boundaries are frequently in a state of flux, as populations shift. For example, for many centuries my father’s comune was Bleggio; within the past decade or so, his area became part of the comune of Comano.

Note that comuni are the keepers of local CIVIL records.

Frazioni

The word frazione (plural frazioni) literally means ‘fraction’, but a better translation would be ‘village’ or (in many cases) ‘hamlet’. Sometimes, instead of frazione, you might see the terms contrada, località (which be just a few houses in a rural area) or maso/mansu (a homestead for a single or extended family).

Unlike comuni, the boundaries of rural frazioni tend to withstand change over the centuries. This is because they aren’t really administrative entities, but simply inhabited places that have become a part of the landscape. Their names might change slightly (as is normal for anything linguistic over time), and they are also likely to have local dialect variants. My grandmother’s frazione of Bono, for instance, has been in existence by that name for at least 800 years, but local people (especially in the past) often called it ‘Boo’ (‘Boh’) in dialect.

LINKS: Resources for Italian Civil Entities

As civil structures are often confusing, here are two good websites for navigating through Italian civil architecture:

-

- indettaglio.it – http://italia.indettaglio.it/eng/index.html. The link is for the English version of the site. On the left side of your screen, you will find links to the regions, provinces, towns and villages of Italy.

- Comuni Italiani – http://www.comuni-italiani.it/. This site provides similar information to the one above. It’s not in English, but navigating is fairly intuitive, even if you don’t understand Italian.

ECCLESIASTICAL STRUCTURE: How the Catholic Church is Organised

While understanding the CIVIL structure of Italy is surely important, it is arguably even more important that a genealogist researching in Trentino (or anywhere on the Italian peninsula) understand the ECCLESIASTICAL structure of the Roman Catholic Church.

Like the State, the Church also has a hierarchical structure overseeing the administrative and spiritual needs of its congregations. While the Pope in Rome is at the top of this chain, for our purposes, we only need to consider the part of this hierarchy with ‘diocese’ at the top.

In English, this is:

Diocese –> Deanery –> Parish –> Curate

Or, in Italian:

Diocesi –> Decanato –> Parrocchia (Pieve) –> Curazia

Diocese

As you can gather from this breakdown, a diocese oversees the operations of many parishes.

SOME dioceses are roughly analogous to a civil province or a region in Italy, but not all.

The (civil) Province of Trento is indeed covered by ONE diocese, also called ‘The Archdiocese of Trento’ (Arcidiocesi di Trento). The term ‘archdiocese’ does not mean it has jurisdiction over other dioceses. Rather, it refers to a diocese with a very large Catholic population, typically including a large metropolitan area. It may not be as large in terms of square miles as other, less densely populated, dioceses.

The head of a diocese is the Bishop; similarly, the head of an archdiocese is the Archbishop.

The geographic boundaries of the diocese of Trento have remained mostly unchanged throughout the centuries, regardless of the civil political situation. Thus, the Diocese of Trento is the most stable and important source of historical information for the Trentino genealogist.

Deanery

Called decanato in Italian, a deanery is a kind of ‘mother parish’ overseeing the operations of a group of parishes in the same geographic area.

For the genealogist, it can be useful to know the decanati overseeing your ancestors’ parishes, as they may sometimes contain duplicate records OR may have been the sole repository for another parish records during a certain era. Having this information can be especially useful when you reach a dead end in your research and have no idea of where to go next.

Like comuni, the boundaries of deaneries have sometimes shifted as populations have shifted, in order to ensure smooth administrative operations. Knowing when and how these changes occurred can also be helpful for the genealogist.

Parish

The parish (parrocchia or pieve) is the church entity with which most readers will be most familiar. A parish refers to the geographic parameters within which people of the same faith (in this case, Roman Catholic) attend the same church.

In Italian, the priest who is the head of a parish is called its parroco or pievano. Often translated as ‘parish priest’, many English speakers may be more familiar with the term ‘pastor’.

The geographic parameters of most large parishes in Trento have been fairly stable throughout the centuries, although they may have fallen under different deaneries over the years. Like the diocese, parishes really are cornerstones of genealogical research.

Curate

A curate church/parish (curazia) is a kind of ‘satellite’ parish, subordinate to the primary parish church.

Many rural areas will have curate churches that serve their local community because the main parish church is some distance away. These curate churches will often deliver Sunday Mass, and sometimes marriages and funerals; baptisms, however, will usually take place at the main parish church.

Curate churches to not normally keep their own parish records; rather, the main parish church will do that for them. Some curate churches become large enough to become independent parishes, offering baptisms, and maintaining their own records (but the main parish church is likely to keep duplicates).

In your research, you might see the records for a curate church suddenly stop. This is usually an indication you have reached the point in time before it had become entitled to keep its own records. For example, Romallo only started keeping its own records in the 20th century; before then, all its records were kept in the parish of Revò.

Thus, it is essential for a genealogist to know the connection between the main parishes and curate churches in their ancestors’ geographic area.

Article continues below…

The Diocese of Trento as Both Church and State

While many other dioceses in the world have shifted over the centuries, the parameters of the Archdiocese of Trento have remained pretty much unchanged for many centuries, despite many shifts on the civil landscape.

The first appointed Bishop of Trento was San Vigilio. Martyred on 26 June 405 C.E., his tomb is located (and viewable) in the crypt beneath the Duomo of San Vigilio in the city of Trento. He is the patron saint of both the city of Trento and all of Trentino. Throughout the province, you will find churches dedicated to him and frescoes depicting his life and death.

Under the order of Emperor Conrad II in the year 1027, this ecclesiastical diocese of Trento was further defined as the civil ‘Bishopric of Trento’. With this, the diocese became an official State of the Holy Roman Empire. In other words, the Bishop now became a state official, and was now called the ‘Prince-Bishop’ (Principe Vescovo). Thus, while still a priest bound by the orders of the Church, he was also minor royalty, with responsibilities to the Emperor as well.

This Bishopric of Trento remained in place for almost 800 years, until Napoleon dismantled the office, and indeed the entire Holy Roman Empire.

But, the DIOCESE of Trento itself still remains. The geographic parameters are unchanged; its bishops are still bishops of the Church.

In short, regardless of whether Trentino has been under control of the Rhaeti, Romans, Longobards, Holy Roman Emperors, French, Austrians or Italians, the PROVINCE and the DIOCESE have remained mostly unchanged (with a few exceptions) for the past 1,600 years.

When we consider this remarkable tenacity of both province and diocese, and the fact that these two administrative offices – both state and church – have always been virtually identical geographically –

We begin to understand why the people of Trentino and their descendants abroad identify so deeply with the PROVINCE over and above anything else.

And for the Trentino genealogist, ‘province’ in our case is synonymous with ‘diocese’ in terms of where we will want to look for vital records. Thus, we need to turn our attention now to how and where these records have been organised within the diocese.

Civil vs. Church Records

So many of us in the English-speaking world have grown up under a political ideology espousing the ‘separation of church and state’.

But in Trentino, and indeed throughout most of Europe, this concept simply didn’t exist until relatively recently. It wasn’t until around the time of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic invasions (at the end of the 1700s and early 1800s) that the office of the Prince Bishop in Trentino was abolished. Prior to then, church and state were inextricably intertwined.

So many of us are accustomed to think that ‘official’ documents for births, marriages and deaths are the domain of the state. And, yes, in Italy in you can obtain civil records from the registry office in your ancestors’ comuni – but only from the 19th century onwards. Prior to the early (and in some places, mid) 1800s, there simply WAS no such thing as a ‘civil’ vital record.

Rather:

Vital records were NOT the domain of the state, but of the CHURCH.

It was, in fact, at the ‘Concilio di Trento’ (Latin: Concilium Tridentinum), which many English speakers may have seen written as ‘the Council of Trent’ in history classes, which took place between 1545 and 1563, that parishes were mandated to record all births, marriages and deaths within their congregation. Thus, while Italian civil records do not typically go beyond the beginning of the 1800s, CHURCH records (at least notionally) go back to the mid-1500s.

I say ‘notionally’ because not all records will have survived that far back, owing to damage from water, fire, wars and (sometimes) general neglect. That said, a remarkable number of volumes HAVE survived the centuries. Moreover, we of Trentino descent are extremely lucky because the Diocese of Trento is the ONLY diocese in the whole of Italy to have digitised ALL their parish records, and then some. The Archivio Provinciale of Bolzano appears to be in the process of doing the same.

Of course, aside from vital records, there have always been legal documents, such as Wills, land agreements, court disputes, etc., In Trentino, these were SOMETIMES kept by the comune, and SOMETIMES kept in the parish (admittedly, it is often confusing). But these are not the kinds of documents MOST genealogists are likely to consult, except those who are more advanced, and are seeking to deepen their understanding (or find evidence of) a specific event, era or person.

Thus, it is the body of work called the registri parrocchiali (‘parish registers’ or ‘parish records’) that is always the primary focus for anyone researching their Trentino ancestry.

These parish registers for Trentino are not owned by the state, but by the Diocese of Trento.

Catholic Deaneries and Parishes in the Diocese of Trento

There are over 400 parishes in the diocese of Trento, each falling under the ecclesiastical care of one designated deanery.

The 1,100+ page book Guida Storico – Archivistica del Trento by Dr Albino Casetti has been the ‘bible’ reference book on the archives of the province for almost 60 years. When he published this book in 1961, there were 25 deaneries in the diocese of Trento, which I have organised alphabetically below:

25 Deaneries of the Diocese of Trento

-

- Ala

- Arco

- Banale

- Borgo

- Calavino

- Cembra

- Civezzano

- Cles

- Condino

- Fassa

- Fiemme (Cavalese)

- Fondo

- Levico

- Malè

- Mezzolombardo

- Mori

- Pergine

- Primiero

- Riva

- Rovereto

- Strigno

- Taio

- Tione

- Trento

- Villa Lagarina

Some of these deaneries may have changed since Casetti’s publication, but as most genealogy projects go backwards in time (probably starting before 1961), these changes should not affect our genealogical research.

Hold this list in your mind’s eye, as we’ll come back to it shortly.

GEOGRAPHICAL STRUCTURE: The Valleys of the Province of Trentino

In this modern world, where we can get to just about anywhere by plane, train, bus or automobile, few of us consider geography as a factor in how and why communities are born and evolve.

A glance at the geographic landscape of Trentino is a great teacher in this regard. A rolling panorama of mountains, valleys and glacial rivers, it possesses a kind of ‘ready-made’ zoning of habitable lands. Before modern roads and motor vehicles, crossing these boundaries wasn’t impossible, but it was certainly not something you did every day.

In fact, marriages and migrations across these boundaries don’t show up frequently in parish records until the late 19th century. And when they do show up in earlier centuries, they are immediately noticeable to the genealogist as something unusual, and certainly significant.

Toponymy and Genealogy

One of the most useful books I have found on the study of Trentino valleys and the place names within them is Toponomastica Trentina: I Nomi delle Località Abitate (The Study of Trentino Place Names: The Names of the Inhabited Localities) by Giulia Mastrelli Anzilotti.

The word ‘toponymy’ (sometimes spelled ‘Toponomy’) means the study of place names, especially their linguistic origins and their evolution throughout history. While the word is rarely seen in the English language, toponomastica is an EXTREMELY common subject in books on Italian history.

For Trentino genealogists, the study of place names is often linked directly to genealogy. Many surnames – especially those in more remote rural areas – are derived from the names of places OR the other way around.

The Valleys of Trentino

Anzilotti has chosen a most useful – and highly visual – way to organise her study of place names: by looking at them within their respective valleys in the province. When I first found this book, I was immediate drawn to her minimalist presentation. I have seen many books with maps of Trentino valleys, but they are usually very cluttered, making it difficult to see the lines distinguishing one place from another.

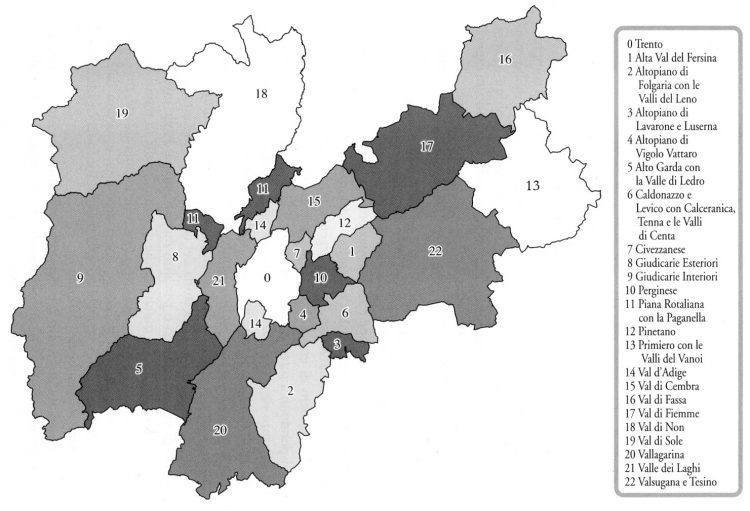

Here is a map of the valleys of Trentino as it appears at the beginning of Anzilotti’s Toponomastica Trentina:

Click on image to see it larger

Click on image to see it larger

For the purposes of being able to make these 23 names searchable, here they are in text form.

She assigns the number ‘0’ for the greater metropolitan area of the CITY of Trento. Then, the valleys are numbered from 1-22:

-

- Alta Val del Fersina

- Altopiano di Folgaria con Le Valli del Leno

- Altopiano di Lavarone e Luserna

- Altopiano di Vigolo Vattaro

- Alto Garda con la Valle di Ledro

- Caldonazzo e Levico don Calceranica, Tenna e le Valli di Centa

- Civezzanese

- Giudicarie Esteriori

- Giudicarie Interiori

- Perginese

- Piana Rotaliana con la Paganella.

- Pinetano

- Primiero con le Valli del Vanoi

- Val d’Adige

- Val di Cembra

- Val di Fassa

- Val di Fiemme

- Val di Non

- Val di Sole

- Vallagarina

- Valle dei Laghi

- Valsugana e Tesino

Anzilotti then works through these areas, listing all the inhabited places found within each, down to the smallest homestead. Basically, if people have lived there and it has a name, she’s listed it and given some sort of linguistic interpretation of its origins. I feel like she may have missed a few (I’ll address those in future articles) but for the most part, it really is a gem of a work.

A few linguistic notes for those who don’t know Italian:

-

- ‘Val’ is the usual singular form for ‘valley’; the plural can be either ‘valli’ (masculine) or ‘valle’ (feminine).

- ‘Alto’ (‘alta’ in feminine) means ‘high’. The word ‘altopiano’ means ‘the high plain’.

- ‘Di’ means ‘of’; before a vowel, the ‘i’ is dropped and an apostrophe is inserted.

- ‘Del’ (singular) and ‘Dei’ (plural) mean ‘of the’.

- ‘E’ means ‘and’.

- ‘La’ (singular) and ‘le’ (plural) mean ‘the’ when it is before a feminine noun.

- ‘Con’ means ‘with’

A note before we continue…

Some of you might disagree with how she’s organised and labelled these valleys. For example, the city of Trento is usually included in ‘Val D’Adige’, and Val Rendena is often considered its own valley, whereas she has included it with Giudicarie Interiore.

Nonetheless, I feel her work is a good starting point, especially as the author has some extremely useful and easy-to-read maps of each valley later in the book, which I will share with you as we go along through this series.

Thus, I ask that you go with the flow with me, even if you disagree with Anzilotti’s designations.

TRENTINO VALLEYS: The Relationship Between Places and People

Something common amongst the people of Trentino is they nearly always refer to themselves as coming from a specific valley. This is because each valley is like a container of a unique subculture, illustrated by their local languages, names and customs.

Different valleys often have different dialects. My father, for example, spoke only the Giudicaresi dialect with his parents and siblings, not Italian. People from Val di Non speak Nones, an altogether different dialect.

Because of the insular nature of these valleys, many surnames will indigenous to one valley. And when you see one of these surnames suddenly appearing in a different valley, it is an immediate indication that a branch of the family has migrated.

Knowing which surnames are indigenous to specific valleys (if not specific parishes) is of vital importance to a Trentino genealogist. This knowledge can often help you identify anomalies and solve many mysteries quite quickly. For example, a new client recently came to me saying her family were named Flaim, and they came from Banale in Giudicarie Esteriore. Well, I knew well that the surname ‘Flaim’ was not native to the Giudicarie but was, rather, indigenous to the parish of Revò in Val di Non. This knowledge immediately led me to look for the point of entry at which a Flaim had migrated from Revò to Banale, as I knew I could trace the family further back from that point.

Valleys, Deaneries, Parishes and People

While a cursory glance over our two lists of valley vs. deaneries, we can see many names (e.g. Cembra, Civezzano, Fiemme, Garda, Pergine, Primiero, Lagarina and the city of Trento) that would seem to indicate they are referring to roughly the same part of the province. But other areas are less obvious to those unfamiliar with the geographic layout of Trentino. So, how do we make sense of what is where?

At this point, a curious genealogist will certainly be asking:

-

- Which parishes are in each valley?

- What are the deaneries for my ancestors’ parishes?

- Which parishes share the same name as their comuni (or NOT)?

- What are the names of the frazioni in these parishes/comuni?

- Who lived in these parishes? What were the most common surnames?

- Where might I find my own ancestors’ surnames?

While I don’t have the ability to answer every question every reader will have, over the course of the next (several) articles in this series, I will do my very best to share with you what I have learned about these subjects, by dint of my study and my own research.

Coming Up In This Series…

Now that we’ve oriented ourselves with the ‘meta’ structures of Trentino at a civil, ecclesiastical and geographical level, we’re ready to explore them in more detail.

In the next article in this series, I would like to start our investigation by looking at the greater area of the CITY of Trento – its neighbourhoods, suburbs, parishes and a bit about the surnames. As part of that, I’ll be sharing some very interesting (and little known) information from a book called Libro della Cittadinanza di Trento by Aldo Bertoluzza. You can find it here:

After exploring the city of Trento, I’m going to shake things up a bit. I’m NOT going to go through Mastrelli’s valleys in order, but discuss them somewhat at random, to keep you surprised.

(Psst! The next article after Trento

will be about Val di Non.

But don’t tell anyone!).

For each valley we explore, I will be listing its comuni and parishes, and the deaneries overseeing the parishes. Whenever I have some experience researching in a particular area, I will share some of the main surnames I have found there. If I am aware of parishes changing boundaries or status at different points in history, I will again share what I know.

To be honest, I can’t predict exactly what it’s all going to look like. But I promise it will be relevant to Trentino family historians…

…and I will do my best not to make it as sleepy as Sister Rose Winifred’s geography class.

I do hope you’ll subscribe, so you can receive the rest of this special series delivered to your inbox. You can do so via the form at the bottom of this article.

If this article has sparked your interest to keep reading about this topic, it would mean so much to me if you could take a moment to leave a few comments below, sharing what you found most helpful or interesting about the article, or asking whatever questions I may not have answered.

Until next time!

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

23 Jan 2020

P.S. My next trip to Trento is coming up in March 2020. My client roster for that trip is already full, but if you would like to book a time to discuss having me do research for you on a future trip, I invite you to read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, we can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://trentinogenealogy.com/my-tree/

REFERENCES

ANZILOTTI, Giulia Mastrelli. 2003. Toponomastica Trentina: I Nomi delle Località Abitate. Trento: Provincia Autonoma di Trento, Servizio Beni librari e archivistici.

CASETTI, Albino. 1961. Guida Storico – Archivistica del Trento by Dott.

SERAFINN, Lynn. 2019. Ethnicity Vs. Cultural Identity. Trentino, Tyrolean, Italian?