Surnames and occupations in the city of Trento in 1800s, and frazioni of Trento today. Part 3 of ‘Trentino Valleys, Parishes and People: A Guide for Genealogists’ by Lynn Serafinn.

Last time in this special series on Trentino valleys, we looked at the CITY of Trento before the year 1600, including an examination of the fascinating Libro della Cittadinanza of 1577. We also looked dozens of surnames from that era, and considered how their spelling has changed over the centuries.

If you haven’t yet read that article, I invite you to check it out at https://trentinogenealogy.com/2020/04/trento-city-surnames-1600/

What I Will Discuss in this Article

Today, I’d like to continue our exploration of the city of Trento by leaping forward a few centuries to the 1800s.

In this article, we will explore:

- The various FRAZIONI (hamlets/villages) that are now part of the civil municipality of Trento.

- A demographic overview of the city of Trento in 19th century, including POPULATION, LANGUAGES, LITERACY and OCCUPATIONS.

- A list of SURNAMES in the city at that time, as per the 1890 survey.

My reason for choosing this era is twofold. First, there was a detailed SURVEY of the city of Trento made in 1890, which provides us with a fascinating snapshot of life in the city at that time. And secondly, as this was the era when so many of our ancestors started to emigrate from the province, this information helps put some historical context about what life was like at that time (in the city, at least).

REMINDER: This article is only about the CITY of Trento, NOT the rural parts of the province of Trento (also called ‘Trentino’). After we finish our discussion of the city, we’ll start our exploration of the many rural valleys and parishes of the province in detail, spread across at least 20 upcoming articles in this special series.

The Municipality of Trento TODAY

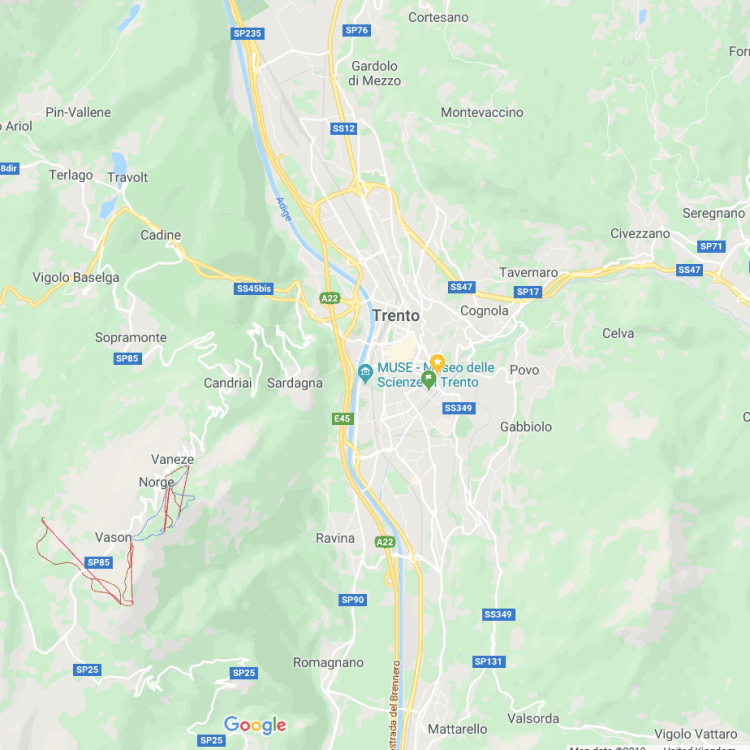

Courtesy of Google Maps, the image below will give you a rough idea of how the greater municipality of Trento is laid out TODAY.

Please note that I couldn’t manage to get Meano (which is north of the visible area of this map) or Villazzano (which is south of the visible area) to show up without the labels of many of the others disappearing.

Frazioni of the Municipality of Trento

Below is a list of frazioni and their subdivisions, which are currently part of the municipality of Trento.

I have organised most of these frazioni according to how they appear in the book Toponomastica Trentina: I Nomi delle Località Abitate by Giulia Maistrelli Anzilotti; I’ve added a few that she did not include in her book.

Note that, in the 19th century, many of these were classed as independent comuni; the villages Cadine, Cognola, Gardolo, Mattarello, Meano, Povo, Romagnano, Ravina, Sardagna and Villazzano, for example, were not aggregated into the municipality of Trento until 1926. Moreover, some of these were classes as frazioni of some of these former comuni. Gabbiolo, for example, was once considered part of the comune of Povo.

| FRAZIONE | SUB-FRAZIONI AND NEIGHBOURHOODS |

|---|---|

| Bolleri | Bolleri vecchia; Bolleri nuova |

| Cadine | |

| Campotrentino | |

| Candriai | |

| Centochiavi | |

| Cimirlo | |

| Cognola | Maderno; Martignano; Tavernaro; Villamontagna |

| Cristo Re | |

| Gabbiolo | Gionghi |

| Gardolo | Palazzine; Spini; Steffene |

| Lamar | |

| Man | |

| Mattarello | Mattarello di Sopra; Mattarelli di Sotto; Acquaviva; Novaline; Palazzi; Ronchi; Valsorda |

| Meano | Vigo Meano; Camparta Bassa; Cirocolo; Cortesano; Gorghe; Gazzadina; San Lazzaro |

| Moia | |

| Montevaccino | |

| Piedicastello | |

| Povo | Casotti di Povo; Celva; Dosso Moronari; Mesiano; Oltrecastello; Pante'; Ponte Alto; Sale'; Spre' |

| Ravina | Belvedere |

| Romagnano | |

| San Martino | |

| San Nicolò | |

| Sardagna | |

| Settefontane | |

| Solteri | |

| Sopramonte | Pra della Fava |

| Spalliera | |

| Valle | |

| Vela | |

| Vigolo Baselga | |

| Villazzano | Castello; Negrano |

Trento in the First Half of the 19th Century

You might recall that, in the last article, I spoke about a book by Aldo Bertoluzza called Libro della Cittadinanza di Trento: Storia e tradizione del cognome Trentino, which he published in 1975. In that article, we looked at Bertoluzza’s analysis of the 1577 document called ‘Libro della Cittadinanza di Trento’. Today, we move forward in the book (and in time) to pages 46-58, where Bertoluzza discusses various surveys that were carried out by the civil authorities of Trento in the 19th century.

It’s worth remembering that the taking of censuses or demographic surveys was not a regular practice prior to the beginning of the 19th century. Surely these surveys existed, but they were inconsistent and certainly not standardised. From 1809, after Napoleon invaded the province and abolished the office of the Prince Bishop, we start to see some regularity to such records. While Napoleon’s personal political victories were short-lived, the maintaining of a civil registry is still practised throughout the province.

As civil records were still in their infancy in the early 1800s, the parameters for their body of statistics are often unclear and inconsistent. A demographic survey of the city of ‘Trento’ might not always include the same areas, which often makes it difficult to compare one set of statistics to another.

Trento in 1809

To illustrate that point, a survey of Trento taken in 1809 included not just the area within the city walls, but also the frazioni of Cognola, Povo, Ravina and Sardagna, resulting in a total population of 15,204 people.

Trento in 1821

In contrast, in 1821, in addition to Trento, Cognola, Povo, Ravina and Sardagna, the survey included statistics from FIVE MORE frazioni: Mattarello, Gardolo, Romagnano, Montevaccino and Villamontagna.

Despite these additions, the population seems to have declined since the earlier survey, now showing only 10,863 residents. I don’t know if this reflects a true decrease, or the parameters of who they decided to count had changed (I am inclined to think the latter).

Trento in 1842

By the year 1842, the greater municipality had grown by more than 14% to 12,408, with 8,556 of these living within the city walls.

Although Bertoluzza does not say which frazioni were included in that survey, he does provide us with some interesting statistics regarding possidenti – property owners – both within the city and in its outlying, rural areas. According to the 1842 survey, there were 437 possidenti who owned property within the city walls that year, whose total real estate include 2,200 urban properties and houses. But now, we also learn that there were 201 contadini (farmers) who owned property, spread across 700 units of land – presumably, this included farmland, pastures, and meadow land.

Aside from the possidenti, the survey counts 2,100 ‘mercenary individuals’ (presumably referring to military in residence there) and an additional 2,656 people who were either part of the Church (priests, nuns, etc.) or merchants. (I have no idea why they decided to lump those two categories together!)

What I found most interesting about this survey is how it shows the number of family homes within each of these areas. Below is a table showing them in descending order:

| PLACE | NO. OF FAMILY HOMES |

|---|---|

| Trento (presumably, within the city walls) | 1,118 |

| Cognola | 212 |

| Mattarello | 179 |

| Gardolo | 175 |

| Ravina | 105 |

| Sardagna | 94 |

| Romagnano | 63 |

| Montevaccino | 46 |

| Villamontagna | 42 |

This brings the total number of family homes to 2,034 in that year. Using this data, Bertoluzza calculates the average size of the family household was between 6-7 people in that era.

I find it interesting to see how small some of these frazioni were, even though they were part of a ‘city’. Even the population within the city walls itself is surely not exceptionally large.

1890 Survey of the City of Trento

Finally, in the year 1890, we begin to see some more rigorous statistics – and useful information for genealogical research. I am sure this is why, on pages 48-58 of Libro della Cittadinanza di Trento, Bertoluzza provides us with a COMPLETE transcription of the population survey made by the municipality of Trento in the year 1890, followed by many pages of his own and demographic analysis of the same.

Bertoluzza presents most of the findings in paragraph format, which can sometimes make it difficult to assess and compare the key data. Below, I’ve compiled some of the demographics into tables for your perusal.

1890 Demographic Overview

According to the 1890 survey, in less than 50 years, the population seems to have exploded to 21,486 residents – and increase of 9,078 people (over 73%). Unfortunately, I cannot say for sure that this covers exactly the same geographic area as the 1842 survey, as Bertoluzza doesn’t specify; perhaps it isn’t even specified in the survey, as the information was presumed to be known. Again, this means we cannot do a precise comparison between this survey and those of previous years, but it does give us a general picture of overall urban growth.

Here are some general statistics about who was living in Trento at the time:

| TOTAL POPULATION OF THE CITY | 21,486 |

|---|---|

| NUMBER OF FAMILIES | 3,313 |

| FULLY LITERATE | 12,327 |

| SEMI-LITERATE | 960 |

| ITALIAN SPEAKERS | 18,957 |

| GERMAN SPEAKERS | 2,350 |

| SPEAKERS OF OTHER LANGUAGES | 169 |

Two details especially stand out to me:

- Nearly 60% of the urban population was fully literate. I would be willing to guess the literacy rate here is significantly higher than in the rural parishes during the same era, most likely due to the kinds of occupations urban citizens tend to have compared to the valley dwellers (we’ll look at these in a minute).

- Over 88% of the population said Italian was their first language (but we can surely assume many native Italian speakers could speak German, and vice versa). As all the records I have ever seen from the province during this era are written in Italian, I am not particularly surprised at this, but I find it interesting considering how many people who emigrated from the province (which was steadily increasing around this time) identified themselves as ‘Austrians’.

Occupations in Trento in the Year 1890

Bertoluzza goes on to give a full breakdown of the professions of the people of the city of Trento in that year. He puts them in a paragraph in alphabetical order, which is a bit hard to wade through, so I’ve copied in some of the highest figures along with some of the more interesting professions on the list, and organised them according to their number, in descending order. I haven’t included every single profession he listed, but I did end up listing most.

| PROFESSION | NO. OF PEOPLE | PROFESSION | NO. OF PEOPLE |

|---|---|---|---|

| MILITARY | 1,821 | RUGMAKERS | 36 |

| DOMESTIC SERVANTS | 1,511 | MECHANICS | 31 |

| FOREIGN STUDENTS | 1,081 | CAFÉ OWNERS | 27 |

| AGRICULTURAL/ FARMING | 1,070 | JEWELLERS | 26 |

| TAILORS | 676 | HOTELIERS | 26 |

| DAY WORKERS (odd jobs, etc.) | 627 | WEAVERS | 19 |

| PRIESTS/ NUNS, etc. | 455 | CLOCK/ WATCHMAKERS | 18 |

| MASONS/ BRICKLAYERS | 333 | SADDLE MAKERS | 17 |

| PUBLIC OFFICIALS AND SERVICES | 321 | CARVERS/ ENGRAVERS | 16 |

| CARPENTERS | 318 | LITHOGRAPHERS | 14 |

| STONECUTTERS | 269 | ARTISTS | 13 |

| COBLERS / SHOEMAKERS | 261 | SALAMI MAKERS | 13 |

| POOR (so, no job listed) | 215 | UMBRELLA MAKERS | 12 |

| PERSONAL TEACHERS | 198 | WOODCUTTERS/ SAWYERS | 9 |

| RETIRED | 176 | CHAIRMAKERS | 6 |

| HOSTS (at tavern or hotel) | 163 | CHIMNEYSWEEPS | 6 |

| BLACKSMITHS | 149 | ENTREPRENEURS | 6 |

| SEAMSTRESS/ NEEDLEWORK | 132 | GLASSMAKERS/ GLAZIERS | 5 |

| SILK WEAVERS | 123 | WOOL WEAVERS | 5 |

| BAKERS | 108 | CEMENT MAKERS | 4 |

| HEALTHCARE PERSONNEL | 96 | GOLD AND SILVERSMITHS | 4 |

| BUTCHERS | 58 | STRING/ TWINE MAKER | 4 |

| WINE MAKERS | 58 | KNITTERS | 4 |

| BOOKSELLERS | 48 | GLOVE MAKERS | 3 |

| PAINTERS (house/ buildings) | 47 | HARMONICA AND ORGAN MAKERS | 3 |

| BARBERS | 46 | PASTA MAKERS | 3 |

| LAWYERS AND NOTARIES | 46 | SOAP MAKERS | 3 |

| RAILWAY WORKERS | 45 | MATCHSTICK MAKERS | 3 |

| ENGINEERS AND SURVEYORS | 42 | BRICKMAKER | 1 |

| COPPERSMITHS | 39 | BROOM MAKERS | 1 |

Some Comments and Context

- MILITARY: I do find it interesting that the profession with the highest number is the various military personnel. There are no details given about who they were, but we know they would have been from the Austro-Hungarian Army, and possibly originating from outside the province.

- DOMESTIC SERVANTS: During this era, it was extremely common for young WOMEN to become domestic servants prior to marriage. Sometimes their duties included being governesses to young children; my grandmother and her sister were governesses when they were in their late teens. Sadly, there are many accounts of abuse of young women when they were in service in the 19th century – a topic I will address in a later article.

- FOREIGN STUDENTS: While not a paid occupation, I include this number on the list, as students constitute a significant percentage of the population counted. While compulsory education was already in effect in the Austro-Hungarian Empire during this era, ‘students’ here is surely referring to adult students, not children. This would most likely include seminary students. Here, they are recorded as ‘foreign’, but it doesn’t specify if this means they were from outside the city, outside the province, or from another country (perhaps it was a combination of all three). Also, no mention is made regarding local students.

- AGRICULTURAL: The number given is a cumulative one, including agricultural landowners, farmers, tenants, and agricultural labourers/assistants. Thus, it is hard to know how many of these were actual farmers. We can presume that the bulk of these were from the frazioni on the periphery of the city.

- ECCLESIASTICAL: Of those in ecclesiastical professions, 343 were priests, and 112 were nuns.

Comparison to Rural Communities

Clearly, the demographic profile of the city of Trento is significantly different from what we see when we look at the parish records for our Trentini ancestors in rural parishes. In those places, when professions are listed, they nearly always say ‘contadino’ (feminine = contadina), meaning a subsistence farmer. While I have no official statistics, based solely on my own observations, I would hazard a guess that a good 90% of the population would have described themselves a ‘contadini’ until the 20th century, even if they did other jobs to provide additional income (especially during the winter).

Poverty Level

One thing I find remarkable about this breakdown is that 215 people of the total number are described as ‘poor’ (and thus have no profession listed).

If we are to take this figure at face value, only 1% of the population of the city was living in poverty in 1890, a figure that most modern cities have never come close to attaining. For example, New York City – a place where so many Trentini immigrants settled only a generation after this survey of Trento was taken – released its annual report on poverty in May 2019, saying their poverty level had ‘dropped’ to from 20.6% (in 2014) to 19% in 2017.

It certainly makes me wonder as to the accuracy of the statistics and, if they are indeed accurate, as to the reasons for such a stark difference between poverty levels then and today.

Article continues below…

Some Surnames in the City of Trento in 1890

There is no way I could possibly list all the surnames on the 1890 survey, as there are just so many, but to give you a TASTE of some of the surnames in the survey, I’ve gleaned some from the list that I think might be recognisable to many of my readers. Please note that the original list contains no surnames starting in E, Q, X or Y. Also, Bertoluzza stresses that he has not ‘fixed’ any spelling errors, so the surname might again be spelled somewhat differently from how you might usually see it (I’ve tried my best to catch any typos of my own):

- A: Altemburger, Ambrosi, Andreatta, Andreis, Andreotti, Anesi, Angeli, Avancini.

- B: Baldessari, Beltrami, Benedetti, Benigni, Benuzzi, Berlanda, Bernardelli, Bertini, Bertoldi, Bertolini, Bonazza, Bonenti, Bortolotti, Bresciani.

- C: Cagliari (Caliari), Callegari, Cappelletti, Carli, Cattoni, Catturani, Cesarini, Ceschi, Chiappani, Chistè, Chiusole, Ciani, Cognola, Conci, Corradini, Covi.

- D: Dallago, Dallachiesa, Dallapiccola, Dalrì, Dante, Decarli, Degasperi, Depaoli, Donati, Dorigatti, Dorigoni, Dossi.

- F: Fachinelli, Faes, Falzolgher, Fedrizzi, Felin (Fellin), Ferrari, Filippi, Fogarolli, Folghereiter, Fondo, Formenti, Fracalossi, Franceschini, Frizzera, Frizzi, Fronza, Furlani.

- G: Garavaglia, Garbari, Gennari, Gentilini, Giacomelli, Giongo, Giordani, Giovannini, Girardi, Giuliani, Gius, Gnesetti, Gottardini, Gressel, Grossi.

- H: Hamberger, Hochner, Hoffer, Huber.

- I/J: Innocenti, Joriatti, Juffmann.

- K: Kaiser, Kargruber, Kettmajer, Kein, Knoll, Koch, Kofler, Krautner.

- L: Laner, Larcher, Largaiolli, Lazzeri, Lenzi, Leonardelli, Liberi, Lisimberti, Lodron (specifically Count Carlo), Longhi, Lorenzi, Lucci, Lunelli, Lutterotti.

- M: Maestranzi, Maffei, Magnago, Maistrelli, Majer, Malfatti, Manara, Manazzali, Manci, Marchetti, Marconi, Margoni, Marietti, Martignoni, Mattasoni, Mattivi, Matuzzi, Mazzi, Menapace, Menestrina, Menghin (Menghini?), Mensa, Massenza, Michelloni, Monauni, Monegaglia, Moratti, Moser, Mosna.

- N: Nadalini, Nardelli, Nardoni, de Negri, de Negri Pietro, Negri, Negriolli, Nichellatti, Nicolussi, Nones.

- O: Oberzzauch, Oberziner, Olivieri, Olneider, Onestinghel, Ongari, Oss.

- P: Palla, Panato, Panizza, Paoli, Paor, Paris, Parisi, Parolari, Pasolli, Pedroni, Pedrotti, Pegoretti, Peisser, Penner, Perghem, Pergher, Permer, Pernetti, Perzolli, Peterlongo, Petrolli, Piccinini, Piccoli, Piffer, Pintarelli, Pisetta, Pisoni, Planchel, Pligher, Podetti, Pollini, Pollo, Postinghel, Proch, Pruner, Puecher.

- R: Ranzi, Ravanelli, Recla, Redi, Rella, Rigatti, Rohr, Rossi, Rizzieri, Rungg.

- S: Salvadori, Salvotti, Sandri, Santoni, Sardagna, Sartori, Schmalz, Schreck, Scotoni, Secchi, Segatta, Sforzellini, Sicher, Sidoli, Sironi, Sizzo, Sluca, Stanchina, Stenico, Stolziz.

- T: Tabarelli de Fatis, Tagini, Tamanini, Tambosi, Taxis, Tecilla, Thun, Toller, Tommasi, Tommasoni, Tonioni, Tononi, Torrelli, Torresani, Tranquillini, Travioni, Trentini, Turrini.

- U: Untervegher (that’s the ONLY letter ‘U’).

- V: Vais, Valentini, Vanzetta, Veronesi, Viero, Visintainer, Vitti, Volpi, Voltolini.

- W: Waldhart, Webber, Widessot, Wolkenstein, Wolff.

- Z: Zambelli, Zambra, Zamboni, Zampedri, Zanella, Zanini, Zanolini, Zanolli, Zanollo, Zanotti, Zanzotti, Zatelli, Zeni, Zippel, Zottele, Zotti, Zucchelli.

As you read through this list, please bear in mind:

- Although the survey counted all the residents, the NAMES in the survey are only of the property owners.

- If you do see your surname here, it does not necessarily mean these specific individuals are related to you.

- Seeing your surname here also does not necessarily indicate an ancestral link to the city of Trento. Many (if not most) city dwellers have their origins in other parts of the province (or beyond).

- ALL names containing the letters ‘K’ or ‘W’ are Germanic in origin, as these letters are not used in the Italian language.

Bertoluzza’s Study of the History of Trentino Surnames

As I’ve drawn the information for this article primarily from Bertoluzza’s Libro della Cittadinanza di Trento: Storia e tradizione del cognome Trentino, it would be remiss of me not to mention what constitutes the lion’s share of the book, even though it is not directly connected to today’s topic.

Bertoluzza’s forte is as a linguistic historian of names. Indeed, on pages 31-41 of Libro della Cittadinanza, he illustrates how different surnames have their origins in personal names, nicknames, place names, animal names, occupations, etc. Then, from pages 63-211, he gives a detailed study of the history of specific Trentino surnames. Interestingly, virtually none of these surnames appear either in the 1577 Libro della Cittadinanza or in the 1890 survey of the city of Trento. In fact, the majority of these surnames appear in various valleys around the province, and not in the city at all.

It does make me scratch my head a bit because it is difficult to understand why all these disparate pieces of work appear in the same book. But I’ve found this kind of ‘patchwork’ approach to be the case in several other Trentino histories, to be fair.

I cannot help but feel that this 1975 publication was a precursor to Bertoluzza’s ‘bible’ of surnames, Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino, which he published in 1998. That book has long been my ‘go to’ source of information on the history and evolution of Trentino surnames. Still, Bertoluzza’s study of surnames in his (perhaps misleadingly titled) Libro della Cittadinanza di Trento has some details that appear to have been edited out and streamlined for his more well-known Guida; I think it really is a goldmine of information.

If you can read Italian and you’re a serious researcher, I do recommend trying to find a copy of this now out-of-print gem of a book.

Coming Up Next Time: The DEANERY of Trento

This article has focused on looking at the city of Trento since the beginning of the 19th century through the lens of its nature as a municipality, governed by a civil administration.

But while this information is surely useful in helping us understand everyday lives of the citizens of Trento and its frazioni, for us as genealogists, it is far more important to understand the ecclesiastical organisation of the deanery of Trento.

So, next time, we will look in detail at:

- The CATHOLIC PARISHES that come under the DECANATO (deanery) of Trento.

- The CURAZIE (curate parishes) within each of these parishes.

- FRAZIONI that are part of the municipality of Trento , but NOT part of the deanery of Trento (e.g. Meano).

- The SURVIVING PARISH REGISTERS that are available for research in each of the above.

Once we’ve finished our genealogical tour of the city of Trento, we’ll move on to our tour of the rest of the province – starting with an exploration of VAL DI NON.

I hope you’ll join me for the upcoming instalments in this series ‘Trentino Valleys, Parishes and People: A Guide for Genealogists’. To be sure to receive these and all future articles from Trentino Genealogy, simply subscribe to the blog using the form below.

Until next time!

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

22 May 2020

P.S. As you probably know, my spring trip to Trento was cancelled due to COVID-19 lockdowns. However, I do have the resources to do a fair bit of research for many clients from home, and will have some openings for new clients from 15 June 2020. If you would like to book a time to discuss having me do research for you, I invite you to read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, we can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://trentinogenealogy.com/my-tree/

REFERENCES

ANZILOTTI, Giulia Maistrelli. 2003. Toponomastica Trentina: I Nomi delle Località Abitate. Trento: Provincia Autonoma di Trento, Servizio Beni librari e archivistici.

BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1975. Libro della Cittadinanza di Trento: Storia e tradizione del cognome Trentino. Trento: Dossi Editore.

And Google Maps.