Genealogist Lynn Serafinn discusses the challenges of researching women in parish records, and how to find your great-grandmothers through the centuries.

A note before we begin: Although this article is about finding your female ancestors from Trentino, many of the research strategies discussed can be applied to finding your female (and male) ancestors from anywhere parish records are used to record births, marriages and deaths. If you are not yet familiar with how to find and access parish records from Trentino, be sure to subscribe to this blog, as I will discuss that topic in a later article.

Many of us strongly identify with our surname. Thus, many people will begin their genealogical journey by tracing the lineage of male ancestors with the same last name. However, when constructing a surname lineage, results will be limited. Even if you were to trace your patrilineal surname lineage back to your 11x great-grandparents* (which might take you back to the second half of the 1500s, when parish records in Trentino began), your tree would have a total of only 27 people: you, your two parents, your two paternal grandparents, your two paternal great-grandparents, and so on.

*SIDENOTE: ‘11x great-grandparents’ is shorthand for great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great- great-great-grandparents’ (i.e. the word ‘great’ eleven times).

While constructing a surname family tree is a natural part of exploring our identity, genealogically speaking, it is only a tiny fraction of who you really are. The real ‘juice’ of genealogy is when you start to explore the rich and diverse heritage you have received from your many, many great-grandmothers. After all, 50% of your DNA is from the women in your family tree, and each of those women has a mother and a father. If you do some number crunching, if you trace your complete ancestry back to your 11x great-grandparents, you could theoretically have as many as** 8,192 great-grandparents, half of whom (4,096) are women.

Even if you are not 100% Trentini, and you have only one Trentini grandparent, you could still have as many as** 1,024 female Trentini ancestors who are probably listed somewhere in the parish records.

**SIDENOTE: I say ‘as many as’ because that’s the highest number you get if you multiply each successive generation by two. However, the number is most likely to be somewhat smaller, as Trentini families typically intermarried. For example, let’s say your 10x great-grandparents had two sons who married and had children. Then, many years later, the 5x great-grandson of the first son married the 5x great-granddaughter of the second son. Many years later, you became a descendent of that marriage between the 5x great-grandson and the 5x great-granddaughter. That means your 10x great-grandparents are your ancestors via two different branches of the family. This kind of intermarriage will ‘collapse’ your family tree at various points, meaning it will reduce the number of ancestors you actually have. I’ll talk about this in more detail in a future article.

The Challenges of Finding the Names of Women in the Parish Records

The challenge in Trentino, and I imagine in other parts of the world as well, is that women’s names were not always documented as thoroughly as they are today. From my experience, this is generally what you can expect to see in parish records.

Baptismal Records

In ALL cases, the names of the priest and the godparents are given in the baptismal records, but the names of the parents and other family members are variable throughout the centuries:

- 1500s – The name of the mother of the child is often completely missing. The name of the father is always given, and the name of the father’s father is frequently given. The father’s frazione (village) of origin is always given.

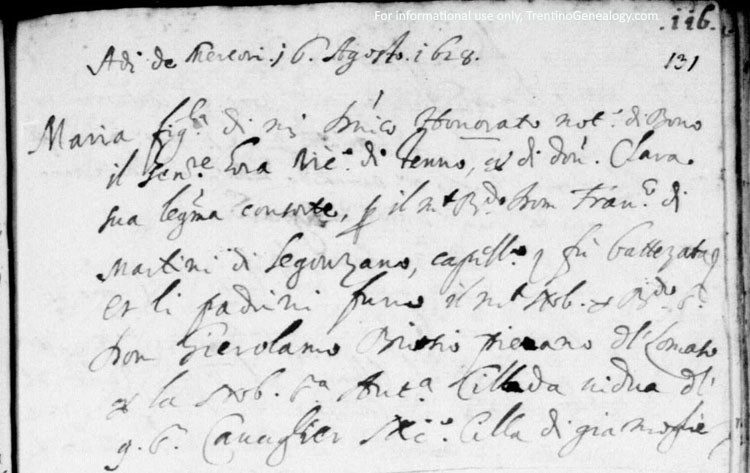

- 1600s – The first name of the mother is usually given, but not her surname (remember, Trentini women maintain their father’s surname throughout life). As before, the name of the father is always given, the name of the father’s father is usually given, and the father’s frazione of origin is always given.

Click on the image below to see it larger.

- 1700s – It gradually becomes the practice over the century to include the full name of the mother’s father (hence, you know her surname), and also her frazione of origin, especially if it is different from the husband’s. As before, the name of the father, the father’s father, and the father’s frazione of origin are given.

- Early 1800s – After 1806, printed templates are used for the parish records, with specific columns for the information. This makes the records far more detailed and consistent. From this point, you will normally find the surnames, fathers’ names and frazione of both parents of a child, but not the names of the mothers of the parents. Sometimes you might see a cross next to a child’s name, indicating they died not long after their birth.

- Late 1800s into 1900s – From about 1880, you will start to see the names of both parents, as well as the full names and village of origin of both sets of grandparents of the child. Some priests will also list the name of the midwives, and make a note if the child is the couple’s firstborn. As you approach the 20th century, some priests will also go BACK to baptismal records many years later, and enter the person’s marriage date and/or death date somewhere on the baptismal record. If the person emigrated abroad (increasingly common), they might make a note of that date as well.

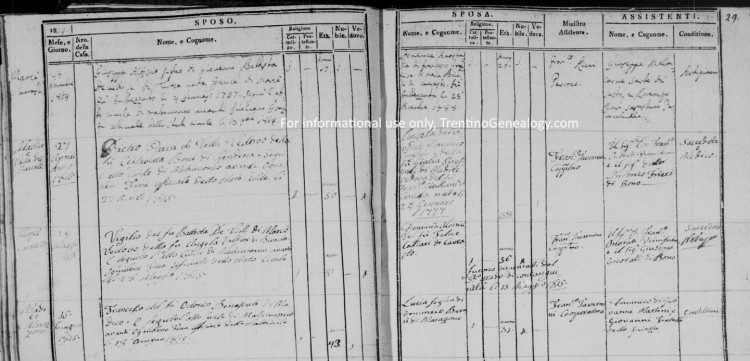

Marriage Records

In all marriage records, you will find the full name and village of origin of the fathers of both the bride and the groom. As in the case with baptismal records, you will start to see the names of the mothers of the bride and groom appear in the records towards the latter part of the 1800s, as well as the ages (and sometimes date of birth) of the bride and groom.

Click on the image below to see it larger.

Death Records

Prior to the late 1800s, the death record for an unmarried woman typically designates her as the daughter of her father, while that of a married woman will designate her as the wife (or widow) of her husband. Sometimes, if the deceased is a young child, you might see the name of the mother as well as the father. Death records for men tend to provide even less information, as they designate the man as the son of his father, and almost never mention the wife. Thus, unless the priest has written down the age of the person at the time of death (and you already have a good idea of when he/she was born), it can be difficult to know whether you’ve found the record you’re looking for. As in the baptismal records, from the latter part of the 19th century, you will start to see more complete details in the records of both men and women, including the names of their parents and spouse, and the dates of birth and marriage. Be aware, also, that some parishes started keeping death records much later than they started recording baptisms and marriages.

The Science of Genealogical Detective Work

Given these factors, finding your female ancestors further back than the middle of the 19th century can be significantly more challenging than finding your male ancestors (which can be challenging enough!). Still, finding your female ancestors can be done if you take a systematic approach in your research.

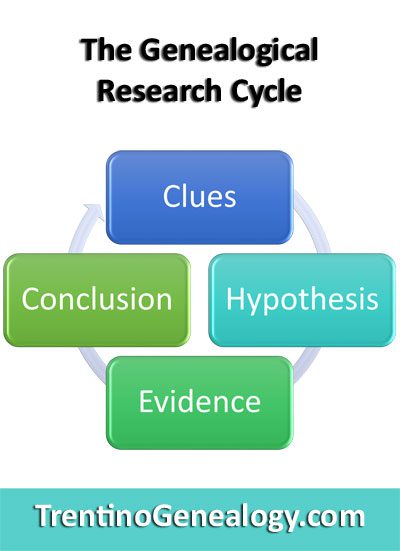

Good investigative genealogy is a scientific process. Like all science, it all boils down to a 4-step system:

- Looking for clues

- Use the clues to formulate a hypothesis

- Use your hypothesis to find evidence

- Use your evidence to draw a conclusion

Once you have drawn conclusions, the cycle starts all over again, as you begin to look for clues to answer the next batch of questions that will inevitably arise.

Let’s take a look at how to apply that system to finding your female ancestors.

Lateral Thinking – How to Uncover Crucial Clues

Looking for clues involves lateral thinking. This means you need to expand your scope of research to include not only your direct ancestors, but also their siblings. There are many important reasons for this. First, the very clue you seek may be in the birth or marriage record of a sibling, and not in the record of your direct ancestor. Second, as I discussed in my previous article, ‘How Much Do You Really Know About Your Ancestors’ Names?’, families tended to name their children after other members of the family, including elders and recently deceased siblings. Thus, the only way to make sure you have found the correct person – and not a dead sibling, cousin or someone unrelated – is to construct the whole family as completely as possible. Once you have the family constructed, you can make some hypotheses to help you locate evidence about your female ancestor.

For example, let’s say you know the name of your 5x great-grandfather in the 1700s, and you are trying to find out more about his mother, your 6x great-grandmother. You’ve managed to find the baptismal record of your 5x great-grandfather, which gives the full name of his father, but only the first name of his mother. In this case, you would need to look for all of your 5x great-grandfather’s brothers and sisters. Go backwards and forwards, continuously looking for children of the same father, where the father is married to a woman with the first name. Statistically, MOST of the time, there will be only one couple with that name during those years. Occasionally, you will encounter the genealogist’s nightmare: two men with the same first/last name married to two women with the same first name, but I’ll talk about how to get around scenarios like that in a later article. For now, let’s assume there is only one possible couple who meet the criteria of your 6x great-grandparents.

Typically, children were born continuously anywhere between one and three years apart. Even those who died soon after birth will be listed in the baptismal records, as they were often been baptised within hours of having been delivered. In fact, when you see two children born only about a year apart, it can sometimes be an indication that the first of these children died in early infancy (as, biologically, a woman cannot ordinarily become pregnant again until she has finished nursing the previous child). If you stop seeing children after five or more years in either direction, it is likely that you’ve reached the beginning/end of the childbirths for that couple.

SIDENOTE: The ‘gap’ theory is NOT always applicable to families after the 1880s. From that time, many men were spending extended periods of time working in the coal mines in the United States, coming home to their families every few years. In those cases, you might see big gaps (sometimes as much as eight years) between the births of children. One example is Elisa Serafini in the photo at the top of this article. Her two children, Angelina and Costante Painelli, were born 7 years apart because her husband Ambrogio was working in the mines in Pennsylvania between 1904 – 1909.

Click on the image below to see it larger.

Forming a Hypothesis from These Clues

Constructing a family group like this can give you a lot of very important clues about your 6x great-grandmother, if you know a few things about how your ancestors lived and married. From my experience, following these generalities can be very useful in forming your hypotheses:

- ON AVERAGE, most Trentini couples had their first child about a year after they married. So, if you know the birth of the first child was in February 1707, you can form a hypothesis that the couple married sometime around 1705 or 1706.

- ON AVERAGE, most Trentini women tended to be about 21 years old at the time of their first marriage, with a more general norm of anywhere between 18 and 24. Younger than 18 was uncommon. Older than 24 was possible if there were a lot of daughters of marriageable age in her family, or she was widowed and in her second marriage. There was no such thing as divorce in the Catholic families during this period. Thus, if you have formed a hypothesis for her marriage year, you can also form an estimate for her year of birth. In the above example, if your 6x great-grandparents were probably married around 1705, your 6x great-grandmother was probably born between 1681 and 1687, with the most likely date around 1684-5.

- The birth date of the LAST child can also tell you a lot about the dates of birth and/or death of your 6x great-grandmother. Before the late 19th century, when the rate of infant mortality was heart-wrenchingly high, it was the norm for women to give birth to 10, 12, 14 or even 18 children. If your 6x great-grandparents had such a ‘normal’ sized family, you can narrow down your 6x great-grandmother’s birth date by looking at the date of birth of the last child. Statistically, it is reasonable to hypothesise she was between 43 and 45 years old when that child was born. If you balance this against the estimate you made when you looked at her probable date of marriage, you might be able to narrow down her birth date to within a year or two. For example, here’s a screenshot of my 4x great-grandparents, which I shared in the previous article. Margherita Giuliani gave birth to 14 children, born between July 1805 and May 1827. From this information alone, I can hypothesise that she probably married in 1803 or 1804 (up to 19 months before the birth of her first child), and that she was born around 1783 or 1784 (as she would have been 43 or 44 when her last child was born). The parish records show that she indeed married in September 1803, and was born in August 1784.

- The SIZE of the family can also give important clues. Before the middle of the 1800s, if there are fewer than eight children in the family, it could be an indication of the death of either the husband or the wife. If their children were still young, widowed men and women tended to remarry within a couple years of their spouse’s death. So, if you see a small family followed by a gap in the birth records, and then you start seeing a man with the same name having children with a different woman, it could indicate that the man remarried (of course, it could be referring to a different man altogether). If you suspect your 6x great-grandfather remarried, you can estimate the year of death of your 6x great-grandmother by looking at the date of birth of her last child, and the date of birth of her widowed husband’s first child by the new marriage.

Collating Your Clues to Find Evidence

After having constructed the family, you can collate all your clues. Even if you don’t know her surname yet, here’s what you might now know about your 6x great-grandmother that you didn’t know before:

- An estimated marriage year

- An estimated year birth

- Possibly an estimated year of death

At this point, I recommend you enter these estimates into your family tree. I do NOT suggest you put them as fixed dates; rather, use descriptors ‘about’, ‘before’, ‘after’ or (in some cases when I am less sure of the range), ‘between’. That way, you have a guide to know where to start looking to find your evidence.

Once you have these clues, the first thing you need to do is find the MARRIAGE record. Go the marriage records for your ancestors’ parish and look within the estimated time period to find a marriage between a man with your 6x great-grandfather’s name and a woman with the first name of his children’s mother. This is important because the marriage record is the ONLY document where you know for sure you will find the full name of your 6x great-grandmother’s father and, importantly, her surname. Now you can change your estimated marriage year to an exact date.

Here’s something else VERY important to do at this stage: be sure you record the VILLAGE (frazione) of origin of your 6x great-grandmother’s family. Sometimes, knowing the frazione is the only way you can FIND your ancestors, or distinguish them from another family of the same name. For example, in the parish of Bleggio, there are two distinct branches of the now extinct ‘Pellegrinati’ family. One lived in Bivedo and the other lived in Duvredo. Many of them had the same first names. If you inadvertently identify someone as your ancestor from the wrong frazione, you could end up going down entirely the wrong path and waste months of research time.

Armed with all this information, you can then go back to the baptismal records and look for your 6x great-grandmother, daughter of the man you now know is your 7x great-grandfather, born during the estimated time period for her birth in the frazione you found in the marriage record. When you find someone who seems like a likely candidate, go through all the records in the same frazione before/after her for about 10 years. Look for her siblings and keep a record of all of them. If you’re lucky, you’ll also discover their mother’s (your 7x great-grandmother’s) first name. Make sure there isn’t ANOTHER child with the same name from the same couple who might have been born a few years later, lest you enter the wrong information for your 6x great-grandmother.

TIP: Take a moment to review the things we looked at in the previous two articles, regarding soprannome, spelling variations and middle names. Remember: your 6x great-grandmother might be referred to by her middle name in her marriage record, and both her surname and first/middle names might be spelled differently in the baptismal record.

Once you have exhausted all the possibilities using this method, you are (hopefully) ready to draw the conclusion that you have found the woman you are looking for.

Lastly, if your hypotheses include an estimated death date, you can look for the record in the death records. If the record identifies her husband or father, and/or gives her age at the time of death (which is often rounded-off, and rarely precise), you know you have the right woman.

Repeating the Cycle to Grow Your Tree

After you’ve done this for one generation, you’re ready to go back to the beginning of this process and work through it again to locate your 7x great-grandmothers (there are as many as 512 of them!), and continue back as far back as you can go.

What Can You Do When a Mother Isn’t Mentioned at All in a Birth Record?

As I said earlier, in many of the baptismal records from the 1500s, the mother’s first name isn’t mentioned at all. However, if there is more than one man with the same name during the same period, chances are the records will identify one of these men as ‘the son of so-and-so’. In some cases, the priest might notate his soprannome (see my previous article about Trentini surnames). This information can also help you construct family groups of siblings, even if you don’t yet know the names of the mother (or mothers) for these children. If you’re lucky, all the children will be from a single couple. If that’s the case, you can probably find their marriage record fairly easily using the method we’ve already discussed. But sometimes, due to the proximity of births, it becomes obvious you are looking at two different couples. Solving those kinds of riddles can require much closer scrutiny of the records, something I’ll talk about more in future articles.

Coming Up – Finding Parish Records and Thinking Outside the Box

I hope this article has helped give you some ideas about how to start identifying some of the more elusive women who make up your genetic blueprint. If you found it useful, please subscribe to this blog so you can receive future articles. Desktop viewers can subscribe using the form at the right side at the top of your screen. If you are viewing on a mobile device and cannot see the form, you can subscribe by sending a blank email to trentinogenealogy@getresponse.net.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, I am aware that some of you reading this might not know much (or anything) about parish records. For starters, WHICH parish records do you need? How do you obtain copies of them, and how can you understand them? We’ll be looking at that in the next article on the Trentino Genealogy blog.

Later, we’ll also be looking at some ways to ‘think outside the box’ to find your ancestors, such as how looking at the godparents of your ancestors, and what you can learn when you see your ancestors showing up as godparents of other people’s children.

Until then, I always welcome your thoughts, comments OR questions, so please feel free to share them in the comments box at the bottom of this article. And if your family are from Bleggio and you’re looking for help with your Trentini family tree, you are most welcome to drop me a line via the contact form on this site.

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

Subscribe to receive all upcoming articles from Trentino Genealogy! Desktop viewers can subscribe using the form at the right side at the top of your screen. If you are viewing on a mobile device and cannot see the form, you can subscribe by sending a blank email to trentinogenealogy@getresponse.net.

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

View My Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

LYNN SERAFINN is a bestselling author and genealogist specialising in the families of Trentino. She is also the author of the regularly featured column ‘Genealogy Corner’ for Filò Magazine: A Journal for Tyrolean Americans.

In addition to her work for clients, her personal research project is to transcribe all the parish records for the parish of Santa Croce del Bleggio (where her father was born) from the 1400s to the current era, as well as to connect as many living people as she can who were either born in Bleggio or whose ancestors came from there. She hopes this tree, which already contains tens of thousands of people, will serve as a visual and spiritual reminder of how we are all fundamentally connected.

View the Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

CLICK HERE to view a searchable database of Trentini SURNAMES.