Genealogist Lynn Serafinn discusses cultural labels and personal identity, and explores the ethnic history of northern Italy. Article 3 of 4 on DNA Tests, Genealogy, Ethnicity and Cultural Identity’.

In the first two articles in this 4-article series on DNA tests, we focussed on the more technical aspects of genetics, and how it relates to genealogy. If you missed those articles, you can catch up by clicking on the links below.

ARTICLE 1: In which we examined (TOPIC 1) the different kinds of DNA tests and (TOPIC 2) some basics about autosomal DNA.

ARTICLE 2: In which we discussed (TOPIC 3) how DNA tests can often point us in a direction, but (usually) cannot give us specific answers about our ancestry or blood relations.

In today’s article, we’ll be shifting focus slightly as we explore:

- TOPIC 4: Cultural Identity in a New World

- TOPIC 5: What Does History Tell Us About Northern Italian Ethnicity?

While the subject of cultural identity might at first seem a bit off the topic of DNA tests, I believe we cannot clearly understand the findings of any DNA test without first examining who we BELIEVE we are. And, as what we think we are and can sometimes conflict with what other people think we are, knowing more about our historic and ethnic background is also crucial to being able to make sense of what we might receive from DNA testing companies.

In today’s article, I will also address the moral responsibility DNA testing companies have in putting ‘labels’ on different ethnic groups. Just HOW those DNA companies decide what to ‘label’ us will be the subject of the fourth and final article in this series.

TOPIC 4: Cultural Identity in a New World

Nationality vs. Local Identity

For anyone of northern Italian descent, the whole notion of what it means to be ‘Italian’ is challenging, from both a cultural and historical perspective.

‘Italy’ as we know it today was comprised of independent pockets of cultures, republics and city-states for a lot longer than it was ever called ‘Italy’. The regions of Liguria, Lombardia, Veneto and Piemonte were not integrated into the emerging nation called ‘Italy’ until the second half of the 19th century. And the region of Trentino-Alto Adige – comprised of the two provinces of Trentino (AKA Trento) and Alto-Adige (AKA Bolzano or Bozen) was not officially integrated into Italy until 1919*, at the end of World War 1. The people of Trentino, the southern province of that region, are predominantly Italian-speaking (albeit there are many regional dialects), while the people in the province of Alto Adige are predominantly German-speaking (although most will also speak Italian today).

* Emperor Charles I of Austria relinquished his control on 11 November 1918 (what we English speakers refer to as ‘Armistice Day’), upon which Italian forces moved into Trentino-Alto Adige, but the official treaty of Saint-Germain was signed on 10 September 1919.

While independent from one another, most of these northern states were under the banner of the Holy Roman Empire for about 1,000 years, since the time of Charlemagne (ca. 800 AD). Then, after a very brief period roughly between 1790-1814 when Napoleon was busy stirring things up, these states came back under the control of the Austrian and (later) Austro-Hungarian Empires. These empires, by whatever label, were dominated by the royal Hapsburg family for many centuries.

All the regions of modern Italy have rich cultural histories that long predate the idea of a unified nation. Pick up any book on European history and you will read about the power, importance and influence of northern Italian cities – all independent – such as Genova (Genoa), Milano (Milan), Mantova (Mantua), Venezia (Venice), Verona and Padova (Padua). Even Shakespeare used many of these northern cities as the settings for his plays.

But amongst the northern provinces, Trentino, Bolzano and parts of Lombardia were somewhat different. These provinces were known as a ‘bishoprics’ (vescovile), and each was ruled by a ‘Prince Bishop’ (Principe Vescovo) until the Napoleonic era when the government was secularised. During the reign of Prince Bishop Cristoforo Madruzzo, the famous ‘Council of Trent’ (Concilio di Trento) took place in the city of Trento in the mid-1500s.

The office of the Prince Bishop was exactly what it sounds like: he was BOTH royalty AND an ordained bishop of the Catholic church. As a priest, the Bishop could not pass on his property and title to his children (as he was supposed to be celibate and childless), but we frequently see power passing from an uncle to one of his nephews, thus creating dynasties of bishops throughout history. As royalty, the Prince-Bishop was – just as the Emperor was – able to confer titles of nobility to outstanding citizens in his bishopric. Many of my own Trentino ancestors were ennobled by Prince Bishops. Such titles helped strengthen ties of loyalty between the state, the church and its people. It also helped to forge a sense of pride in – and identification with – the greater area known as ‘Trento’.

In addition, the people of Trentino (especially in rural areas) have always had their own localised cultural identities. For example, people typically think of themselves as belonging to a particular valley (Val di Non, Val di Sole, Val Giudicarie, etc.). These valleys, delineated by the glacial mountains, lakes and rivers of Trentino’s breath-taking natural terrain, embraced pockets of rural communities who spoke local dialects and had surnames often specific to a relatively tiny geographic area. In other words, it wasn’t just the bishopric creating a sense of cultural identity, but the land itself.

Given such history and geography, it is unsurprising that the people of Trentino and other provinces in northern Italy did NOT unilaterally adopt a new cultural identity of ‘being Italian’ when national boundaries and governments changed in the 19th and 20th centuries. Even today, many still think reject the ‘label’. Others accept it, but nearly all still tend to identify more strongly with their local culture than with their ‘nationality’. You cannot simply wipe out millennia of local, cultural identity by slapping a new label on it. This is not just true of Italy, but of ALL modern countries, everywhere on the planet.

Unfortunately, the ‘labels’ people receive from DNA tests don’t make things any easier; we’ll come back to this point later in Article 4 of this series.

The Fragile Identity of Youth

When I was 14 (now 50 years ago!), I was invited to a birthday party for one of my male classmates. Now this boy (let’s just call him ‘B’) was arguably the handsomest in our class, and I had had the fiercest crush on him for more than a year. And to be honest, I am pretty sure B had felt some puppy love for me too.

The party was in the basement at B’s house (on Long Island, where I grew up, nearly all of us had finished basements, and these were perfect party places). When the party was over, I was coming up the stairs to go home, and was greeted by B’s father.

Being the 1960s, I always dressed in the ‘mod’ fashion of the times, which meant mini-skirts, fishnet stockings, go-go boots and love beads. And, I had a head of very long, straight, dark brown hair.

As I got to the top of the stairs, B’s father decided to tease me, asking, ‘How do you get that long hair of yours so shiny, Lynn?’

My heart fluttered a bit, because B’s father obviously knew who I was, and I suspected his son had mentioned me as someone he liked.

I replied, ‘Easy. I rinse it with vinegar after I wash it.’ (Believe it or not, that was a common practice back then, especially for dark hair).

He laughed and countered, ‘Ha! Leave it to a nice Italian girl to wash her hair with salad dressing!’

Then, without even a moment’s hesitation, I replied, ‘Oh, I’m not Italian. I’m Austrian.’

He looked at me with perplexity. ‘But your name is Serafinn.’

Again, without even thinking, I said, ‘It’s an Austrian name. My father was born in Austria, but it was taken over by Italy.’

(Side note: When I was 14, I didn’t know that Trentino had already become part of Italy when my dad was born there in 1919).

B’s father looked at me oddly. At the time, I thought it was just confusion over what I had just said. But years later, I realise I was probably insulting him. You see, B’s father was a first-generation Italian-American (their surname was most likely Calabrian).

I hadn’t intended to insult him. I was making no judgment or political statement about Italy. I was simply parroting what my father and my grandparents had programmed me to say since I was a child.

But now, half a century later, I realise that in replying to him the way I did, I was actually distancing myself from him. Not only was a drawing a line of distinction between us, I was probably sending out a subtle vibe that I was rejecting Italy and the idea of being Italian.

B’s father made no reply to me after that, but my words had definitely made some sort of impact on him. After that, his son no longer seemed to be interested in me, and I soon learned he had found a ‘nice Italian girl’ as his girlfriend.

My first case of teenage puppy love ended in heartbreak over a case of cultural identity.

Fuzzy Labels. Fuzzy Sense of Self.

Most of us of Trentino descent who were raised in America referred to ourselves as ‘Tyroleans’. I never even HEARD the word ‘Trentino’ until decades later.

I’m pretty sure my dad had originally told me I was ‘Austrian’ when I was little because it was easier for ‘outside’ people to understand than the more perplexing label of ‘Tyrolean’. Other Americans really had no idea what we meant by ‘Tyrolean’, and it always required some explaining – a skill I learned only as I got older.

Even after I started referring to myself this way, I wasn’t really quite sure what the heck I meant by ‘Tyrolean’. Although my dad had been born in the ‘old country’ and spoke dialect fluently, he had come to America when he was very young and didn’t remember much about his homeland.

When I asked him where he came from, he merely said, ‘Near Trento’. When I asked him if he could be more specific, he said the village he came from was so small, you wouldn’t even find it on a map (perhaps true back then, but that was before Google maps!).

Despite such fuzziness, when I was growing up, my father’s culture was unavoidable. I constantly heard my father speaking dialect with members of his family, as he called them on the phone just about every night after work. And whenever we visited my grandparents, aunts and uncles, everyone spoke dialect. I got used to sitting in a roomful of adults speaking a language I couldn’t speak myself, while somehow following the gist of what was being said.

When I asked my dad the name of the language he spoke, he said ‘Tyrolean’. In my teens, I was a classical musician and an opera singer, so I had become familiar with many Italian words. Eventually, I realised the dialect my father spoke (which I now know was Giudicaresi) had a lot of similarities with Italian. But I was told unequivocally it had nothing to do with Italian. It’s Tyrolean. Period.

When I asked him to teach my how to speak ‘Tyrolean’, he refused, saying he only spoke it, but didn’t know how to explain it. Besides, he argued, why would I need it? He wanted me to ‘be American’. Better to speak English.

So, while I inherited a strong sense of being ‘Tyrolean’, I was also being discouraged from trying to ‘go backwards’ to my ancestral roots. The ‘old country’ was in the past. It was almost like those things were ‘dead’ and gone, and I wasn’t allowed to touch them. I strongly feel this kind of mixed message was one of the strongest factors in my DELAYING my ancestral journey or visiting my father’s homeland until after he passed away.

But what my grandparents and father did not (and probably could not) understand at the time was how this severing of ties with the past would leave me with a very hazy and tenuous sense of self.

Much as they wanted me to feel ‘American’, I didn’t.

Much as I wanted to feel ‘Tyrolean’, it was too vague for me to understand in any satisfactory way.

And ‘Italian’? Are you kidding? Just the idea of such a notion seemed completely taboo.

And now, after working with dozens of genealogy clients over the years – all descended from immigrant families – and have seen this same sense of haziness over and over. It’s heart-breaking to watch.

Losing A Surname – The Cruellest Cut of All

Perhaps the biggest vagary in my cultural upbringing – which, sadly, I now realise was a deliberate lie – had to do with our surname.

Back at the birthday party, I had told B’s father that my surname ‘Serafinn’ was Austrian. This belief was forged by my father, who told me the surname ‘Serafinn’ with two ‘ns’ was specifically a ‘Tyrolean’ name. I remember him telling me, ‘If you ever meet anyone with that name, they are related to you.’

Well, he was partially right. If I ever meet anyone with the surname ‘Serafinn’ with two ‘ns’ they ARE indeed related to me. But it’s not because it’s a Tyrolean name. It’s because my grandfather made it up. Historically, there IS no such surname as ‘Serafinn’. The only people called ‘Serafinn’ were my grandparents, my father, his siblings and their children. Other than us, the surname doesn’t exist.

I found out decades later – well after my father and all his siblings had died – that my father’s surname was ‘Serafini’, not ‘Serafinn’. At first, I rejected the idea my father might have deliberately misled me. I theorised that perhaps he hadn’t known Serafini was the family surname, and that he had grown up thinking ‘Serafinn’ was his real name, just as I had. But then, when I started to dig more deeply, I discovered documents listing my dad as ‘Serafini’ through his teens. While I am not sure of the precise date, the official change seems to have been made sometime in the late 1930s, not long before my dad enlisted in the US Army.

Thus, there was no way my dad and his siblings could have been unaware of our original surname. Yet, all of us kids – me, my sister and my cousins – were never told this when we were growing up. Obviously, it had been a family decision to ‘break’ us from the past.

And because the change of surname was one of those proverbial ‘family secrets’ that died along with my father’s family, the actual reasons for the change can only be hypothesised. Was it simply a matter of simplifying the name for Americans, without changing it altogether? Was it an attempt to make the surname look less Italian and more ‘Austrian’ (which, as we saw in the story with B’s father, didn’t exactly work)? Perhaps it was a bit of both, but we’ll never know for sure.

I must confess, when I first discovered my grandfather had changed our surname, I felt a combination of anger and grief. I was angry for being lied to. But I was also deeply aggrieved for having LOST my ‘true’ surname. Even today, I still find myself having to explain my surname to people, especially when I am in Trentino. Sometimes I just say my name is ‘Serafini’ to make it clearer.

Similarly, I have worked with many genealogy clients whose families changed their surnames after emigrating to the Americas. Sometimes the changes are minor – like a change in spelling to make it easier for people in their adopted country to pronounce the name. But the surnames of many of my clients have been radically changed, sometimes with no rhyme or reason as to how they are connected to the original name. Naturally, they ask many of the same questions and go through the same roller coaster of emotions as I did when I discovered my father’s original surname.

For any of us who have experienced a ‘loss’ of name, finding out about our ancestors is often an integral part of healing that wound. Now, after many years of ‘speaking to my ancestors’ through genealogy, I have finally embraced this change of surname to ‘Serafinn’ as a crucial part of my own cultural identity. It is a poignant and important chapter in our family’s history – the story of what happened to us after we left our ancestral homeland.

Austrian, Tyrolean, Italian?

Something I found remarkable when I started digging into my father’s US documentation after he died was his own sense of confusion about what to call himself.

In many documents he says he was born in Austria. However, technically, this isn’t true. He was born in Trentino in October 1919, after the province had become part of Italy. In one US census, it says he was born in Italy and that his elder sister was born in Austria. Now, technically, this IS true; however, the fact is they were actually born in the same HOUSE (my cousins still own it) in Val Giudicarie. What I found even odder, though, was that in his military registration, he cites his place of birth as ‘Tyrol’ – which isn’t a country at all. In fact, trying to define ‘Tyrol’ is kind of like trying to define the molecules of water in a flowing stream.

If my father, who was BORN in Trentino, had so much difficulty deciding how to describe where he came from, what chance did I have of being any clearer about my ethnicity when I was growing up? And what chance of clarity can there be for grandchildren or great-grandchildren of Trentini emigrants who were not exposed to their ancestral culture in childhood as I had been?

I want to address this label ‘Tyrolean’ because I believe it’s crucial to this whole topic of cultural identity when we are talking about people who came from Trentino-Alto Adige. Tyrol (Tirol or Tirolo) was originally a county, headed by the ‘Counts of Tirol’. When the original dynasty of counts died out in 1363, control of the Tyrol was taken over by the royal Habsburgs. In fact, from that point, the title of the ‘Count of Tirol’ was sometimes assumed by the Holy Roman Emperor himself.

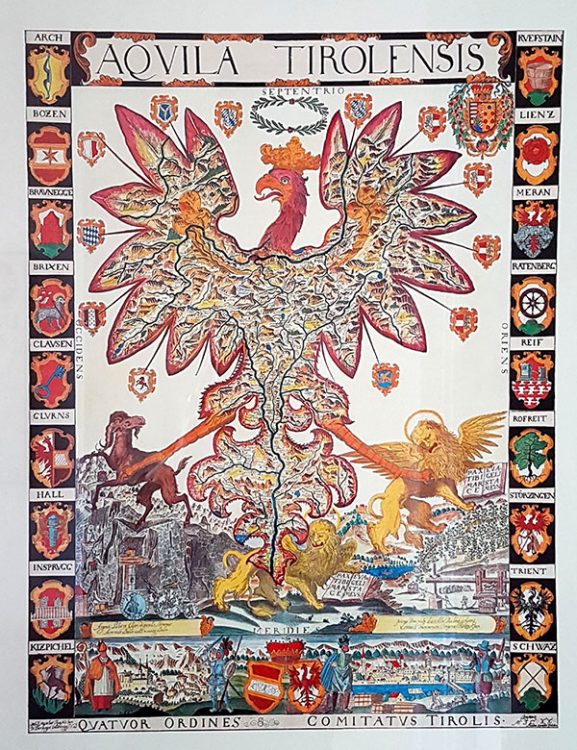

Over time, ‘Tyrol’ no longer referred to a single county, but to a much wider collective, whose connection was often more ideological than administrative. On one of my recent trips to Trento, my friend and colleague Daiana Boller – an historian and local politician – showed me this beautiful painting entitled ‘Aquila Tirolensis’ by 17th-century Austrian historian and cartographer, Matthias Burglechner. First printed in 1609, this version is dated 1620 in the lower right-hand corner. A highly stylised map, it contains the ‘Aquila’ (eagle) of Tyrol – its stemma, or coat-of-arms – and all the key places considered part of it at that time:

If you look closely at the borders of this picture, you can see ‘Trient’ (Trento) and ‘Bozen’ (Bolzano), as well as many other familiar places such as ‘Brixen’ (Bressanone), ‘Arch’ (Arco), ‘Clauzen’ (Chiusa), ‘Meran’ (Merano), ‘Rofriet’ (Rovereto), as well as parts of present-day Austria, such as ‘Insbrugg’ (Innsbruck).

This stunning image gives us an historical snapshot not only of the official designation of ‘Tyrol’ during this era, but also of the diverse cultural identity of the people who thought of themselves as ‘Tirolesi’.

However, let us bear in mind that this painting is 400 years old, and what it depicts is not necessarily what people meant by ‘Tirol’ when our ancestors left the province, nor indeed what most people mean by the term today.

The fact is, the ‘official’ boundaries of Tirol were constantly changing. Frankly, if I try to figure it all out, it just makes my head spin. Rather than attempt to explain it, I refer you to this website with maps showing how these designations shifted after this painting was make, between 1766 and the present day: http://www.zum.de/whkmla/region/germany/tyroladm.html.

But while official boundaries of any administrative entity come and go like tides, the cultural identity of the people from these entities are far more resistant to change.

How Cultural Identities Get ‘Frozen’ in Time

Most descendants of Trentino ancestors know that their ancestral homeland was once under Austrian rule and was incorporated into Italy after World War 1. But, in my observation, fewer of them seem to know that, while the province of Bolzano is still known as ‘South Tyrol’ (Sud Tirol), the province of Trentino hasn’t been known by the term ‘Tirol’ for the past 100 years.

These days, if you say ‘Tyrolean’ to anyone living anywhere in Europe, they always take it to mean Bolzano and/or Austria. And this INCLUDES the Trentini themselves. I have yet to meet a living native Trentino who refers to him/herself as ‘Tirolesi’. In fact, the first time I visited the province and used the word ‘Tyrolean’, people looked at me with bewilderment, if not a bit of amusement.

‘No, Trentino is not Tirol,’ they said. ‘You are confusing it with Bolzano’.

One person who had family abroad said to me, ‘No, we do not call ourselves Tirolesi. But I’ve heard there are some Americans who think like that.’

So, at the risk of ruffling a few of my readers’ feathers, I have to say that all my experiences and observations have led me to conclude that:

The ONLY people today who use the term ‘Tyrolean’ to describe someone from Trentino are descendants of 19th and 20th century emigrants.

In fact, in 1923, an organisation called the ‘Legione Trentina’ actually made it ILLEGAL to use the word like ‘Tirol’ and its variants (Tyrol, Tyrol, Tiroler, Südtirol etc.) to refer to the land now known as Trentino and its people. One leaflet says that by 1931, fines were issued of ‘up to 2,000 lire (about three average monthly salaries) and three months in prison’ for anyone who used these terms.

After all, when most of our ancestors came from Trentino, the province was either still under Austrian rule, or had only just become part of Italy. When they migrated to their new, adopted homelands, the culture – and cultural identity – they brought with them was from THAT era. We, their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, inherited all those things.

BUT the thing is:

When cultures become displaced, the old traditions and ways of thinking do not evolve the same way they would have if they had stayed in their native homeland.

In fact, if anything, they tend to get ‘frozen’ in time. I believe this happens because people who live in places far removed from their ancestral homelands desperately need to feel a connection to their past. And, as they don’t always have any living, breathing connection to those homelands, they will hold onto whatever they’ve got like a life raft.

Moreover, to relinquish that label or change the way of thinking brought across the sea by their emigrant ancestors is seen as a kind of disloyalty – or even betrayal. For this reason, thousands of descendants of Trentino emigrants around the world staunchly retain the a ‘Tyrolean’ (if not ‘Austrian’) cultural identity, despite the fact the label is no longer used by most present-day Trentini.

And no ‘official’ change in nomenclature is going to nullify those powerful feelings.

So, does that mean it’s ‘wrong’ to think of yourself as ‘Tyrolean’? Of course not. Just as my surname ‘Serafinn’ has its own cultural significance, the label ‘Tyrolean’ has its OWN meaning and cultural significance. It doesn’t need to mean what it means in Trentino today or even what it used to mean to our ancestors. It stands on its own as what it is.

For myself, I prefer to use the label ‘Trentina’. And that doesn’t make me ‘wrong’ either. I prefer this term because I have lived in Europe for 20 years, and I go to Trentino frequently. People understand what I MEAN when I use it. So, that designation makes more sense in my situation. But for me, it also carries great meaning. To me, the word represents the thing that makes me feel most connected to my ancestors – the land itself. When I say I am ‘Trentina’, I become part of those glacial mountains, valleys, rivers, lakes and waterfalls. Through that word, I feel connected to every ancestor and blood relation whose very existence was owed to that majestic land.

But that is simply MY cultural label. It has meaning for me, but perhaps not for you. Never EVER in my life would I ever suggest that someone should reject or change the word they use to identify themselves if that word fills them with joy and makes them feel alive.

Schisms Triggered by Cultural Identity

Challenging another person’s chosen cultural designation is, in fact, a sure-fire way to get yourself into an argument.

One such argument within my own family sticks clearly in my mind even after nearly half a century. I was in my teens visiting at the home of one of my father’s sisters, when an argument broke out between my aunt and her cousin (son of my grandmother’s brother, with the surname Onorati).

Our cousin was complaining that he was tired of having to explain to people that he was ‘Tyrolean’, and that now he just told people he was ‘Italian’.

He argued, ‘I look Italian. I have an Italian name. I’m Italian. What’s the big deal?’

At this point, my aunt entirely lost it. She flew into a rage and shoved our cousin against the wall. She started pounding her fists on his chest and screaming, ‘How could you possibly betray our family by saying such things?’

In hindsight, what is most interesting to me about this incident is the fact that this aunt (my dad’s youngest sister) was actually born in America (in Brandy Camp, Pennsylvania) after my grandparents had emigrated with my dad and two other sisters. At the time of this incident, she was in her mid-40s, and had never even been to her parents’ homeland. In fact, she was apparently confused about where they actually came from, as evidenced by a story she wrote about her parents’ mythical home in Merano (in the province of Bolzano) – a place where they never lived.

I bring this up not to criticise my late aunt (I actually adored her), but to underscore how cultural identity has nothing whatsoever to do with cultural awareness. It lives and breathes in complete independence from historical or geographical accuracy.

One of my father’s 1st cousins (whom, unfortunately, I never met) was the late author Marion Benasutti, who wrote a book called No Steady Job for Papa. Marketed as a ‘novel’, it really is a memoire of her experiences growing up in a Trentini immigrant family in the early 20th century (the family emigrated before World War 1). A strong, recurring theme in that book is the ‘Austrian/Tyrolean’ versus ‘Italian’ cultural identity, and how her father used to argue with friends and family members over their chosen designations.

Lest you think these schisms were limited to first-generation Americans, this ideological divide is still very much alive amongst Trentini descendants today. For example, I recently received this message from a prospective member of my Trentino Genealogy Facebook group:

‘I am 100% Tirolean-American. I am interested in tracing our roots back to the days before the Fascist Italianization of our land when it was Austria-Hungary, of which my grandparents were citizens.’

While Austria-Hungary died 100 years ago, and Mussolini died over 60 years ago, the passion contained within these words is still palpable. You can certainly feel how this person would find it challenging – if not impossible – to think of himself as ‘Italian’. To expect (or force) him to do so would not only be highly insensitive, but utterly futile.

Arguably one of the strongest spokespeople for ‘Tyrolean’ cultural identity is Lou Brunelli, founder and editor of Filò: A Journal for Tyrolean Americans. In his editor’s introduction to volume 20 of that magazine (January 2019) he says just as ‘the one and only Tyrol… was ‘usurped’ and ‘annexed to Italy’, the magazine therefore:

‘…usurps the authentic right and privilege to ignore the line and draw a circle embracing, engaging and uniting us to what we were as affirmed by our emigrants who, over and over, declared themselves Tirolesi, Tyroleans and, for us, Tyrolean Americans.’

As you can see, the debate over the cultural identity of Trentino is far from ‘settled’ even after a century has passed.

An Unaddressed Moral Responsibility

I’ve taken this time to talk about cultural identity because I think it has tremendous implications for companies who offer DNA tests.

Whether or not we choose a specific cultural ‘label’, we cannot simply dismiss or ignore them. In my work as a genealogist, most of my clients come from the US, with a handful from South American, Australia and New Zealand. Many of them come to me with a feeling of longing or even emptiness. They are searching for a missing piece of themselves and are often (quite understandably) confused about where their ancestors came from.

Most of the people I know who have taken a DNA test did not embark on their genetic journey just for ‘fun’, but to find answers to deeply personal questions that have been challenging their happiness and/or sense of belonging – sometimes for their entire lifetime.

And, as we’ve just seen, cultural ‘labels’ can often have a powerful – if not EXPLOSIVE – impact on people. You cannot just call people something and expect them to embrace it (or even accept it).

This is something I believe the big companies who handle DNA tests have yet to understand. Knowing how delicate and emotionally charged cultural identities can be, companies who provide DNA ethnicity reports have a HUGE moral responsibility. You cannot play with people’s sense of self – especially not for profit. The labels these companies choose to put on people in their ethnicity reports can sometimes only INTENSIFY the confusion people had that led them to take the DNA test in the first place.

I will be returning to this point in the final article in this series, but for now I want to suggest three crucial shifts that need to occur if we are to increase the value – an minimise the damage – of ethnicity reports offered by DNA testing companies:

- Testing companies need to become more educated about cultural identities around the world, so they can create profiles that are more sensitive and relevant to their customers.

- There need to be greater numbers of DNA test-takers in under-represented cultural groups.

- DNA test-takers need to be more educated about the wider story of the ethnic history of their ancestral homelands.

Only when all three of these things are met can DNA testing truly serve the purpose for which so many people turn to them.

TOPIC 5: What Does History Tell Us About Northern Italian Ethnicity?

Building upon what we’ve discussed so far, the next crucial question we need to ask is:

Does our CULTURAL IDENTITY as ‘northern Italians’, ‘Trentini’ or ‘Tyroleans’ (or whatever) have any foundation in GENETICS?

In other words, are the people from northern Italy genetically ‘different’ from other people, including those from the more southern regions of the Italian peninsula? Or are all these designations simply things we’ve ‘made up’ in order to feel a sense of belonging? Do the DNA tests currently on the market support what northern and southern Italians believe about themselves? Moreover, are their findings consistent from company to company?

We’ll look at the last of those questions in Article 4, when we look at DNA ethnicity reports. But in order to understand what we’ll discuss in that article, let’s first consider northern Italian ethnicity through an historical lens.

Just who were the people who populated Trentino and other parts of northern Italy over the centuries? Below is a short, whistle-stop tour through the millennia.

The Rhaeti and the Celts

About 2,600 years ago, and through the first centuries of the Common Era (A.D.), much of northern Italy was inhabited by Rhaetian and central European Celtic tribes.

Once hypothesised to be related to the Etruscans (ancient people of present-day Tuscany), many scholars today believe the Rhaeti were indigenous Alpine tribes (‘indigenous’ itself being an admittedly vague term). The precise origin of the Celts is much less clear to historians, and many preconceptions about who they were and where they came from are being challenged (although they are most widely believed to have from somewhere in central Europe).

Above is a map showing which languages were spoken around the Italian peninsula circa 600 B.C.

Notice ‘Raetic’ in the orange area at the top, which overlaps with the modern provinces of Trentino and Veneto. The term ‘Gaulish’ in the upper left is another term for Celtic languages. Later, some Rhaeti in south Tyrol (Alto-Adige), Trentino and Veneto, as said to have adopted the Celtic language, at least in part.

Some scholars say that the Alpine language Ladin (NOT the same as ‘Latin’) which is still spoken by an estimated 30,000-60,000 people today (mostly in South Tyrol, Trentino, Belluno and Friuli) is has roots in both Rhaeti and Celtic.

The Romans

Between around 100 B.C. and 400 A.D., Romans were certainly present in places like the city of Trento. There are, in fact, the remains of the old Roman city beneath Trento, but some historians suggest Trento was kind of a ‘holiday spot’ for the Romans rather than a true settlement. Thus, some historians believe the Romans may not have played a huge part on changing the ethnicity of the area, although others dispute this theory.

What is indisputable, however, is that they brought the Latin language, permanently changing the linguistic landscape of northern Italy. The majority of Trentini speak dialects and have names based on Latin roots.

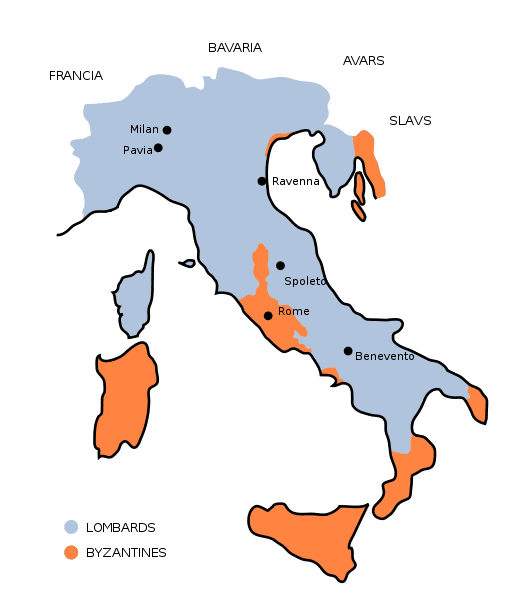

The Longobards (Lombards)

After the fall of Roman (ca. 400 A.D.), we start to see invasions (and settlement) from Germanic and/or Scandinavian tribes. The most notable of these were the Longobards (called ‘Lombards’ in English), from which the northern region of ‘Lombardia’ (or ‘Lombardy’, in English), gets its name. Today, most scholars believe they originated from somewhere in Scandinavia.

A formidable political force, they also influenced many other Germanic tribes – including the Saxons – to settle in Italian lands during their reign. Note: Many people associate the word ‘Saxon’ with England, but they originally came from central Europe; the Germany state of Saxony was once their settlement, before they were defeated by Charlemagne.

The Cimbri and Other Germanic Tribes

During the middle ages (1,000-1,200 A.D.), new waves of Germanic tribes, such as the Cimbri people, migrated and created communities in various parts of Trentino and Veneto. My great-grandmother’s parish of Badia Calavena in the province of Verona is a known Cimbri settlement and, until recently, the people there spoke Cimbro, which, while a distinctly Germanic dialect, also sounds like ENGLISH to my ears. One Veronesi historian I know says he believes this is because Cimbro is related to Old English as spoken by the Saxons. Linguistic connections do not always indicate a genetic connection, but sometimes they might.

What I find so interesting about my great-grandmother’s ancestry, however, is that so many of their surnames – even back to the 1500s – are of Latin/Italian origin, despite their being German speakers. I suppose this is evidence of how long they had lived in that valley, and how thoroughly they had become assimilated into the local culture over the centuries, but again this is pure speculation.

Later Germanic Migrations

Much later, when under Austrian rule in the 1700s-1800s, you will see other scattered Germanic surnames appearing in the church records of the northern provinces, but in a more organic (and less invasive) fashion. As these migrations are relatively recent, you can more easily identify Germanic ‘blood’ through these lines through genealogy alone.

The Ethnic ‘Soup’ of Northern Italy

So, based on what we know about the history of northern Italy, what conclusions can we draw about northern Italian ethnicity?

The truth is, nobody seems to agree.

For example, some historians believe the Longobards, (who comprised an estimated 10% of the population of northern Italy at their peak) had minimal impact the genetic profile of northern Italy because they chose to breed amongst themselves without mixing with other ethnic groups present in the region at the time.

But I’m not so sure. I don’t see how any culture can be in a region for half a millennium and create no impact on the genetic landscape. The Longobards were known to have adopted Roman customs and dress and, although they were always at loggerheads with the Pope, the did actually convert to Christianity.

Given that the Longobards had assimilated, at least in part, to local culture, it seems implausible to me that there was NO inter-breeding between cultures over all that time. My logical brain says at least SOME of that Scandinavian Longobard DNA (and that of all the other ‘imported’ peoples) surely must have mingled – at least to some degree – with that in other ethnic groups in the region.

Moreover, while Charlemagne conquered the Longobard leaders in northern Italy, I cannot imagine they simply ‘vanished’ as an ethnic group. I have seen dozens of Longobard artefacts in many churches and museums in in Trentino. Even the church of my father’s parish in Santa Croce del Bleggio (Val Giudicarie) was built upon the ruins of an old Longobard church.

Even after a political coup, if people have lived in an area for a long time, they tend to stay put, unless they are forced to leave by economic, environmental or political circumstances. And while Charlemagne ousted the Longobard leaders, I have read nothing about any kind of wholesale exodus of the Longobard people from Italy.

At this point, it seems to me the next logical question must surely be:

Can DNA testing shed light on how – or IF – these medieval tribes intermingled?

And if it can…

Will our that DNA profile look different from those of other Italians?

And finally…

What kind of ‘labels’ will DNA testing companies like Ancestry DNA slap on people like us in their ethnicity reports?

Coming Up Next Time…

Those are the questions we’ll address in fourth and final article in the series on DNA tests.

In that article, we will finally look in depth at ethnicity reports – how they come up with their data, what the data means, and how we genealogists – from ALL ethnic backgrounds – can help improve the future of DNA research.

I will also share examples from my own reports, so you can see how data can be interpreted (and misinterpreted) in context.

You can now read that article here:

I invite you to subscribe to the Trentino Genealogy blog, to make sure you receive all the articles in the special series on DNA testing, as well as all our future articles. After the series is complete, I will also be compiling all these articles into a FREE downloadable PDF available for a limited time to all subscribers. If you are viewing online, you will find the subscription form on the right side at the top of your screen. If you are viewing on a mobile device and cannot see the form, you can subscribe by sending a blank email to trentinogenealogy@getresponse.net.

I look forward to your comments. Please feel free to share your own research discoveries in the comments box below.

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

P.S. My next trip to Trento is coming SOON 18 February 2019 through 14 March 2019). If are considering asking me to do some research for you while I am there, please first read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

P.P.S.: Whether you are a beginner or an advanced researcher, if you have Trentino ancestry, I invite you to come join the conversation in our Trentino Genealogy group on Facebook.

Subscribe to receive all upcoming articles from

Trentino Genealogy!

Desktop viewers can subscribe using the form

at the right side at the top of your screen.

If you are viewing on a mobile device and cannot see the form,

you can subscribe by sending a blank email to trentinogenealogy@getresponse.net.

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829