Trentino Genealogist Lynn Serafinn discusses cemeteries in Italy, and shares tips on how gravestones can help you discover more about your ancestors.

Like so many other genealogists and family historians, I love walking through cemeteries. I don’t see them as morbid or spooky, as so much of our popular culture portrays them. I see them as profound expressions of love, admiration, community and social values.

But cemeteries can also be rich sources of historical information, and catalysts that can help us discover many things we might not have known about our families. Sometimes, a random gravestone can turn out to belong to an ancestor, a distant cousin, or a family member of someone else you may not have met yet.

In this article, I want to give you a taste for how cemeteries can help you in your quest for constructing your family history, so you can start to discover and unlock the treasures they may hold. We will look at:

- The Pros and Cons of Working with ‘Virtual’ Cemeteries

- The Limitations and Inaccuracies on Gravestones of Immigrants

- Why There Are No Ancient Graves in Italian Cemeteries

- Parish Cemeteries vs. Frazioni Cemeteries

- How Women Are Recorded on Trentino Gravestones

- Gleaning Information and Identifying People You Don’t Know

- Family Groups on Trentino Gravestones

- How Gravestones Can Reveal More Than Just Dates

- Expanding Your Research and Leaving a Legacy

SIDE NOTE: In addition to the tips in this article, you might also like this VIDEO TUTORIAL I made on a trip to the Trento Municipal Cemetery.

The Pros and Cons of Working with ‘Virtual’ Cemeteries

I’ve observed that descendants of Italian immigrants often want to jump right into finding their ancestors in Italy before taking ample time to gather as much documentation as they can in their ‘adopted’ country. When we talk about Trentini descendants, those countries are typically either the US or somewhere in South America. I recently had a client who lived in England but, like me, had moved here from the US about 20 years ago. This client’s ancestors were not actually from Trentino, but from Genova. Since moving away from her birth place of Chicago, and since the passing away of her parents and other elders of the family, she had lost her connection to the family lore and had little information that could help us get to the point where we could start researching her family’s ancestor in the Italian records.

When I took on the project, the first thing I wanted to do was fill in the blanks of her family AFTER they had emigrated from Italy. For that, one of the most valuable resources was Find-A-Grave, a website containing millions of memorials from cemeteries around the world, all submitted by volunteers. It is, if you will, a collection of ‘virtual’ cemeteries viewable to anyone with Internet access.

Using Find-A-Grave immediately opened a floodgate of information for my client’s family tree. Not only did I find death dates, but many people are linked together, showing connections between spouses, children, siblings, etc. This information enabled me to construct entire families, which I later cross-checked with other online sources like Ancestry and Family Search.

Additionally, some of the memorials contained obituaries from local newspapers, which gave me even more information – including information about when my client’s ancestors first came over from Genova. This led me to find immigration documents. Using what I found in these virtual cemeteries, I was able to glean enough information about her family’s Italian origins to make me confident I could start tackling the Italian records. From there, things became much easier for me, and I quickly managed to take her family tree back to the mid-1700s with a day’s work.

*** FREE RESOURCE ***

Click HERE to download a PDF list of cemeteries in North and South America known to have the graves of many Trentini (aka Tyrolean) immigrants, with links to their pages on Find-A-Grave. No sign-up or email address is required.

But while using Find-A-Grave was a great success on this project, the site does have its limitations.

- All content on the site is provided solely by its users, so the data is as accurate or inaccurate as the people who enter it. TIP: If you see a mistake on a memorial in Find-A-Grave, you can (and should) send a suggested correction to the moderator of that page.

- Not all cemeteries are listed. TIP: You CAN add a cemetery if it is missing (and I encourage you to do so), but be sure to check it isn’t already listed under a slightly different name.

- Most cemeteries listed are in the United States. In fact, there are only a handful of cemeteries listed on Find-A-Grave from the province of Trento (CLICK HERE to see what they are). TIP: Again, I encourage you to add cemeteries you know in Trentino, but if you do, it is wise to enter them under their Italian name. Also, you MUST put ‘Provincia di Trento’ after the name of the comune, as that is how Find-A-Grave refers to and recognises locations in the province.

Limitations and Inaccuracies on Gravestones of Immigrants

While cemeteries can provide us with vital pieces of our ancestral puzzle, my observation of gravestones in our ancestors’ adopted countries (especially the US) is that:

- They often lack detail. Frequently they only have the death date (sometimes only the year), without a date of birth (or at least the year). Even more rarely do they contain much information about who the person was in life, or about his/her relationship within the family.

- They are full of mistakes. Information on gravestones is supplied by a surviving member of the family. Family members – especially children of immigrants – can be inaccurate about dates, names, etc. Back in their ‘old country’, the family would have had access to the original documents via their local parish priest. But without that historic connection to their place of birth, the family has no such stream of information. People who emigrated at a young age (or were BORN in their adopted country) will often mishear, misunderstand, mix up or COMBINE two places, names or events. This results in a muddle of mis-information and false beliefs that will always be some variation on the truth. My cousins, aunts, uncles – even my own parents – were all prone to these kinds of false beliefs. I had to do a LOT of unlearning, relearning and re-educating when I embarked on this genealogical journey.

Equally (and possibly MORE) prone to errors are the obituaries that may have been published in local newspapers. The original information is provided to the newspaper by the surviving family who, as I’ve already said, can frequently get things wrong. Then the newspapers themselves can (and often DO) compound the errors, especially when it comes to the spelling of names and places unfamiliar to them. Birth, marriage and arrival dates will often be wrong, as well. Hopefully they at least get the death date right!

Why There Are No Ancient Graves in Italian Cemeteries

Now, let’s cross the ocean and go back to the patria to have a look at cemeteries in Trentino (or anywhere in Italy).

One of the first things people comment on when they visit an Italian cemetery for the first time is the practice of putting photographs of the deceased on the gravestones. This can be an exciting discovery for the family historian, as they can finally put faces to some of the names they have been researching.

But once they get over that novelty, the next thing they notice – often with some amount of confusion and disappointment – is the ABSENCE of old gravestones. I mean, some of these parish churches go back over 700 years or more; surely we are going to find plenty of fascinating, ancient gravestones in their cemeteries, right?

Well…no.

Yes, you are likely to find old tombs of priests and patron families inside the church dating back many centuries, and you might also find a few older headstones for priests or patrons (perhaps from the 18th century) affixed to the outer walls of the church or perimeter wall of the cemetery. But other than these:

most gravestones are likely to be no older than about 80 years.

This is because, in many European countries, a coffin is exhumed at some point after burial and the skeletal remains are removed from the grave and placed in an ossuary – typically a box, building, well or wall. Then, the same grave is used to bury someone more recently deceased.

This removal of bones has nothing to do with religious practice, but with practical necessity: if everyone who ever died in the parish were put into a coffin and buried under their headstone forever, the space required for the dead would soon take over the land needed for the living.

Just what ‘at some point’ means seems vary in different parts of Italy. I recently read an account where a person’s grandfather’s remains were exhumed only 10 years after he died (the writer expressed some understandable distress). In my father’s parish, however, they appear to wait a couple generations before transferring the bones. That way, the spouse and children of the deceased (and probably most of the people who once knew the deceased in life) are also likely to have passed away. Certainly, this is a more sensitive arrangement.

SIDE STORY: Once when I was showing the underground crypt in Santa Croce to some American cousins, the lady who had unlocked the church for us found a small piece of (very old-looking) jawbone that had fallen out of the wall in a small alcove. She sheepishly whispered a request for us not to say anything about it to anyone, and she respectfully put the bone back into the wall. At the time, I thought she might have been worried teams of archaeologists would descend upon the church and tear it apart. Later, I realised this was probably the site of an ancient ossuary, and she may have wished to avoid upsetting anyone. The crypt itself is at least 1,000 years old, and it was built on the site of an older, Longobard (Lombard) church.

Parish Cemeteries vs. Frazioni Cemeteries

In larger parishes with many frazioni (hamlets) spread out over a wide area, you will often find small satellite churches serving these communities, some of which might have cemeteries of their own. In these cemeteries, you might get lucky and find a few older graves, especially if the family was prominent in that frazione.

For example, when I first went to the main parish cemetery for Santa Croce del Bleggio, I was disappointed not to find the graves of my Serafini great-grandparents, who died in the 1930s. But when I visited the cemetery adjacent the little church of San Felice in the frazione of Bono, where my grandmother’s Onorati family had lived for many centuries, I found the graves of my Onorati great-grandparents who had died earlier, in the 1920s. I believe the reason may be partially due to the Onoratis’ historical prominence in Bono; but the frazione is also tiny, and the cemetery is not nearly as crowded as the main parish cemetery. Some frazioni cemeteries are even larger than the main parish cemetery.

Remember also that married women are most likely buried in the parish (or frazione) in which they lived with their husband. Unmarried women will most likely be buried in the parish (or frazione) in which they were raised. So, when you make your trip to Trentino, be sure to ask whether there is more than one cemetery in the parish. You might discover your ancestors in a place different from where you had expected.

How Women’s Names Are Recorded on Trentino Gravestones

Identifying women on gravestones can often be more challenging than identifying men, as the way they appear will vary according to culture.

For example, because women in the US, Britain and many other countries take the surname of their husband when they marry, they are nearly always referred to by their married names on their headstones when they die in their adopted homeland. In such a scenario, a woman’s gravestone might not be very useful for research, as it doesn’t offer much information about her origins.

In contrast, Italian women retain their maiden names throughout life, even if they have been married for decades. Thus, MOST of the time, a gravestone will give some sort of reference to both her maiden and married name.

There are three common conventions for recording a woman’s name on a headstone. Let’s look at each in turn.

‘Nata’ or ‘N.’ (indicating birth name)

Typically, if a woman is buried in the same plot as her married husband and/or children, she will be referred to by her married name, BUT it will usually have the word ‘nata’ (or its abbreviation ‘N.’), which means ‘born’ (feminine gender).

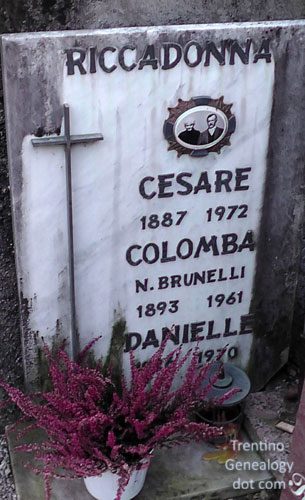

Here is an example from the frazione of Balbido in Santa Croce del Bleggio. The family name is Riccadonna, and you can tell from the photo and the layout of the stone that we are looking at the grave of a husband (Cesare), wife (Colomba) and one of their children (a son named Danielle, born in 1926, although the date is hard to see behind the flowers). Below Colomba’s name it says ‘N. Brunelli’ (nata Brunelli); thus, her birth name is Colomba Brunelli.

Below is another clear example of ‘N.’, from the frazione cemetery in Tignerone in Santa Croce del Bleggio. This is the grave of Ersilia Bleggi, who was born Ersilia Gusmerotti in 1879:

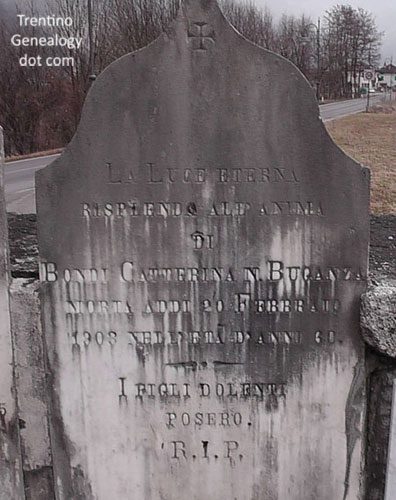

Lastly, here is another example of ‘N.’ on an older, more weather-worn stone from the parish of Saone. On this stone, they have written the surname before the personal name, i.e. ‘Bondi, Catterina, nata Buganza,’ who ‘died on 20 February 1903 at the age of 60’:

‘In’ (indicating married name)

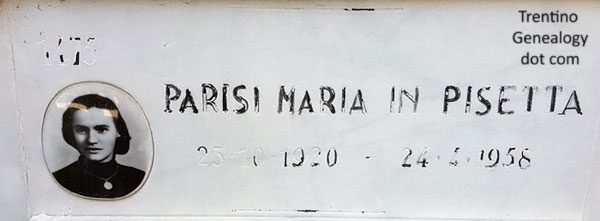

Sometimes a woman’s birth name is given first, followed by her married surname prefixed by the word ‘in’. I have noticed this is most frequently used if the woman happened to be buried in the grave or tomb of her birth family (which could be in a different parish or frazione from her husband’s).

For example, the BIRTH name of the woman in the gravestone below is ‘Giustina Parisi’. But if you look beneath her name, it says ‘in Gasperini’. It’s a little worn, so the ‘I’ is a bit hard to see, but it is definitely ‘in’, not ‘n’. The surname is also partially worn off, but it is definitely Gasperini:

Here is a clearer example of ‘in’ from an ossuary in the Cimitero Monumentale (Monumental Cemetery) in the City of Trento:

‘Vedova’ ‘ved’ or ‘v.’ (indicating she was widowed)

If a woman’s husband predeceased her, she will be referred to as his widow (vedova in Italian) in records and on her headstone. In this case, the stone will give her birth name, followed by the word ‘vedova’, ‘ved.’ or simply ‘v.’, which is then followed by her late husband’s surname.

For example, this placard for Libera Bondi, widow of (someone named) Marchiori, was attached to the top of the family headstone in the parish of Saone in Val Giudicarie (I took this shot in 2016; it may have since been engraved):

The question, of course, is WHO is the late Mr. Marchiori? We’ll come back to that question in a moment.

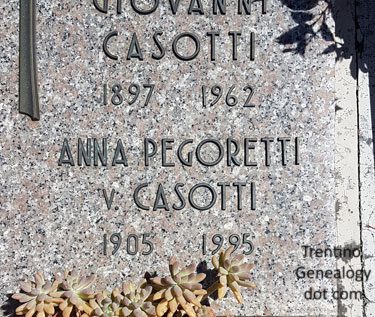

This next stone is from Cimitero Monumentale in the City of Trento. In this case, the woman’s birth name was Anna Pegoretti and she was married to Giovanni Casotti, whose name is right above hers. You can see he predeceased her by more than three decades. The fact that Anna is cited as his widow indicates she never remarried (and was already almost 60 when her husband passed away):

Gleaning Information and Identifying People You Don’t Know

None of the people whose gravestones I shared above are ancestors of mine. In fact, I took those photos out of a sense of curiosity rather than any specific investigative motive.

But as a genealogist, my natural curiosity often leads me to seek out details about a person I find on a gravestone, even if I don’t know them. When I do, I often discover I am connected to them in some unexpected way.

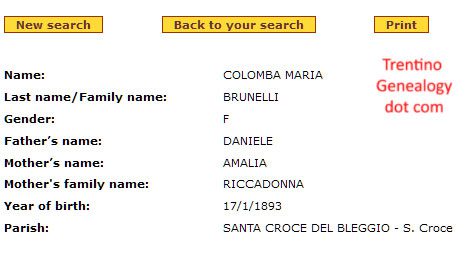

Let’s take Colomba Riccadonna, born Brunelli, from the first gravestone I showed you above. The stone says she was born in 1893.

As she was born between 1815 and 1923, I used the online database created by the Archivio di Trento called Nati in Trentino to find out who Colomba was. All I had to do is plug in her name and year of birth. Luckily, there was only one Colomba Brunelli born that year:

I also used Nati in Trentino to try to identify Cesare, but there were actually two Cesares born in 1887, so I needed to find their marriage record to learn which one he was. I also searched for additional children for the couple and found a daughter born in 1923. They probably had other children, but the online database doesn’t go past 1923.

When I entered Colomba into my tree, I discovered she was a distant cousin (7th cousin 1X removed). Not exactly a close relation, but you never know what such a connection might lead to later.

I used the same process to discover the birth information for Ersilia Gusmerotti, Giustina Parisi and Catterina Buganza, and discovered:

- ERSILIA was my 7th cousin 2X removed.

- GIUSTINA was my 3rd cousin 2X removed.

- CATTERINA was the great-grandmother of one of my clients. I hadn’t planned it that way; I just happened to have taken the photo when I was in Saone on a previous trip. Las month, when I was working on that client’s tree, I looked through my photo archive and discovered I had a picture of her great-grandmother’s grave.

You never really know who or what you will discover when you start taking photos of random gravestones. I could never have predicted a photo I took a couple of years ago would end up being the great-grandmother of one of my future clients. But my client was thrilled to see the photo, as she’s never been to Saone, and this took her closer to her roots.

Family Groups on Trentino Gravestones

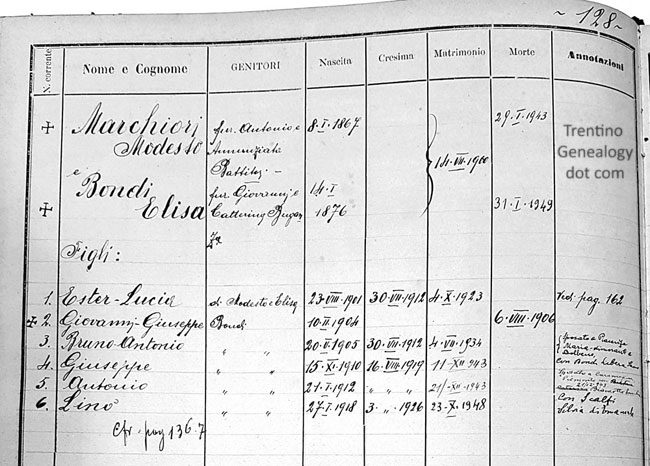

Many gravestones in Trentino will contain names from an entire family group. To demonstrate this, let’s go back to the widowed Libera Bondi and look at the full image of the stone on which she appears:

The primary surname on this stone is MARCHIORI, and the patriarch is Modesto, on the left. To his right, we see ‘Elisabetta Marchiori, born Bondi’. Looking at the dates, we can ASSUME Elisabetta was Modesto’s wife. Of course, we would need to verify that with documentation (I already have, and they were indeed husband and wife).

Moving down the stone, we come to Giuseppe (born 1910) and Antonio (born 1912), with no surname mentioned. The omission of a surname implies they share the same family surname, i.e. Marchiori. Again, looking at the dates, we might guess that Giuseppe and Antonio were the sons of Modesto and Elisabetta. To verify this theory, I looked them up on Nati in Trentino. Sure enough, I found them listed amongst Modesto’s and Elisabetta’s children, along with several other siblings.

But now we have the question of the two women: Emilia (born Biancotto) and Libera (born Bondi). We can assume they were probably married to these two sons. But who was married to whom?

While there is no online resource to answer this question, I was fortunate enough to have access to the family anagraphs for Saone for this era when I was doing research in Trento recently, where I found this entry for Modesto’s family:

Anagraphs (called ‘Stato delle Anime’, or ‘State of Souls’ when they appear in the parish records) are records of family groups and contain a wealth of information, including dates of birth, confirmation, marriage and death. They can also include the names of the spouses in the annotations column at the right. In most places, anagraphs were started in the mid to late 19th century. The various comuni also started recording them in the 19th century, maintaining them at the registry of anagraphs; but so far, I have only dealt with those kept by the church.

In the ‘Annotazioni’ (annotations) column in the anagraph above, the priest has recorded that Giuseppe was married to Libera Bondi and Antonio was married to Emilia Biancotto, with dates of their respective marriages (I know it’s difficult to read here, but I have a larger, full-colour image on my computer that shows it more clearly).

So, while the gravestone didn’t give us all the information we needed, it certainly pointed us in the right direction, giving us clues about what we should look for next. Thus, it was a crucial part of our research.

As it turns out, this family group are ALSO related to my afore-mentioned client, as Elisabetta (Elisa) Bondi was the daughter of her great-grandmother Catterina Buganza, and sister of her grandfather. In other words, Elisa was her great-aunt. Tracing this family helped me identify many of her close cousins.

How Gravestones Can Reveal More Than Just Dates

If you analyse every aspect of a gravestone, you will often find it contains a lot more information than dates alone. Sometimes you can discover a person’s occupation, gain insight into their personal character, or get a feeling for their relationship with their family and community.

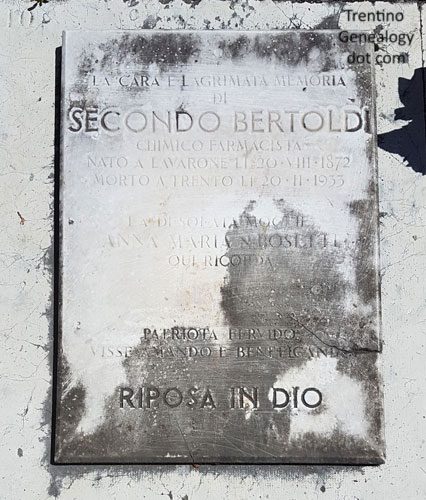

On a recent visit to Cimitero Monumentale in the City of Trento, I took dozens of photos of graves, many of which contained clues about the kinds of people who had been laid to rest. Here are two highlights:

This photo is of the ossuary memorial for a man named Secondo Bertoldi. The stone tells us he was born in Lavarone on 20 Aug 1872 and died in Trento on 20 Feb 1933 (Roman numerals are used for the months). But it also tells us he was a chemist/pharmacist (here in England, pharmacists are also called chemists, but the term is not generally used in the US). Additionally, it says he was a ‘fervent patriot’, and that he lived his life in a loving way and by doing good. It also says that his wife, Anna Maria Bosetti, arranged for this stone to be laid as a ‘loving and tearful memory’ of Secondo. All these words give us a much richer picture of who Secondo was than what we might have learned from documents alone.

Sometimes even the most minimal of headstones can lead to a potentially interesting story. Here’s another photo I took in the ossuary at the Trento cemetery:

The stone merely says ‘Vitti Sisters’, and then gives their first names and years of birth/death. A quick search on Nati in Trentino told me that Giuseppina (born 27 Aug 1888) and her sister Maria (born 15 Oct 1890) were both born in the city of Trento in the parish of Santi Pietro e Paolo (Saints Peter and Paul), and were the only two daughters of Andrea Vitti and Santa Tommasi. The sisters also had two brothers, but I don’t know anything other than their dates of birth.

Apart from this, I know nothing at all about this family. But the fact that these two sisters – both of advanced age (78 and 86) – were laid to rest in the same grave AND they were referred to by their birth names leads me to theorise that neither sister married. It also leads me to think they were probably very close throughout their lives. While these are just my own guesses based solely on what I am seeing in the stone, these guesses might help point me in the right direction if I were to research this family in depth.

Expanding Your Research and Leaving a Legacy

Whether you are planning a visit to a local cemetery, or you are hoping to visit some cemeteries when you are in Trentino, be sure to bring a camera and photograph as many graves as you can, even if you have no clue WHO the people are. If the cemetery is very large – or if the thought of dealing with all those photos is a bit overwhelming – focus on photographing stones containing one or two specific surnames.

And remember, when in Trentino, don’t just visit the main parish cemetery; ask if there are other cemeteries in the frazioni where your ancestors may have lived.

Don’t worry about trying to make sense of who is who when you are taking your photos. That will only slow you down and make it less enjoyable. Look at your trip as a kind of ‘treasure hunt’ where your mission is to get as many good photos as you can. Be sure to get the WHOLE stone in your photo, so you can see all the words in context. They may not mean anything to you now, but they may mean something important later.

And don’t forget that graves in Italy don’t stay around forever. A few years from now…

your photo might end up being the only tangible evidence of a person’s grave,

as the remains and headstone for that person may soon be moved – or removed altogether.

Consider SHARING your images on your tree on Ancestry, as well as on Find-A-Grave. That way, you are not only helping yourself, but also making it easier for OTHER Trentini descendants to find the graves of their own family members. Your photo might mean the world to a complete stranger many years from now.

BRIGHT IDEA: Perhaps we could create a ‘virtual party’ for the purpose of creating all the Trentini cemeteries on Find-A-Grave and entering our family’s memorials on there. We could use our Trentino Genealogy Facebook group to coordinate it. What do you think?

I hope this article has helped you understand more about interpreting gravestones in Trentino, and has also inspired you to go out and start recording as many Trentino graves as you can – as soon as possible, before they disappear.

I look forward to your comments. Please feel free to share your own research discoveries in the comments box below.

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

P.S. My next trip to Trento is from 21 Oct 2018 to 15 Nov 2018.

If are considering asking me to do some research for you while I am there, please first read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

P.P.S.: Whether you are a beginner or an advanced researcher, if you have Trentino ancestry, I invite you to come join the conversation in our Trentino Genealogy group on Facebook.

Subscribe to receive all upcoming articles from Trentino Genealogy!

Desktop viewers can subscribe using the form at the right side at the top of your screen.

If you are viewing on a mobile device and cannot see the form, you can subscribe by sending a blank email to trentinogenealogy@getresponse.net.

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

View My Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

LYNN SERAFINN is a bestselling author and genealogist specialising in the families of Trentino. She is also the author of the regularly featured column ‘Genealogy Corner’ for Filò Magazine: A Journal for Tyrolean Americans.

In addition to her work for clients, her personal research project is to transcribe all the parish records for the parish of Santa Croce del Bleggio (where her father was born) from the 1400s to the current era, as well as to connect as many living people as she can who were either born in Bleggio or whose ancestors came from there. She hopes this tree, which already contains tens of thousands of people, will serve as a visual and spiritual reminder of how we are all fundamentally connected.

View the Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/161928829

CLICK HERE to view a searchable database of Trentini SURNAMES.