Theories and evidence on the origins of the Comini of Val di Sole, and fascinating tales of the noble Comini de Sonnenberg. By genealogist Lynn Serafinn.

Theories and evidence on the origins of the Comini of Val di Sole, and fascinating tales of the noble Comini de Sonnenberg. By genealogist Lynn Serafinn.

If you read this blog regularly, you know I am always fascinated by the origins of Trentino surnames. I get especially curious when I encounter a surname that seems to be associated with one particular village, or that is said to have originated from outside the province.

One such surname that popped up while researching the families of a few of my clients was ‘Comini’. Initially, I was curious because it wasn’t all that common, and also because I had also seen a surname ‘Comina’, and I wasn’t sure whether the two were variants of the same surname or were unrelated. Some of books I consulted seemed to ‘lump’ the two names together, but the more I investigated, the more I felt this was incorrect. Then, when I dug more deeply into the Comini themselves, I started seeing evidence of two completely different lines, living in the same village of Cassana in Val di Sole, but who arrived there at different points in time.

In this article, we will first explore the various origin theories for these two surnames in Val di Sole, from both a linguistic and geographical perspective. Then, we will investigate how and where these surnames appear in documentation from the 1500s, with inferences to the 1400s. After this, we will focus our examination on the Comini in Cassana from a genealogical perspective, to see how two different family lines bearing this surname arose in that village in the 1600s. Focusing then on one of these lines – the Comini de Sera – we will follow it through to one specific family known as ‘Comini de Sonnenberg’, who were ennobled in 1799. Finally, we will take a look at the lives of a few of the famous personalities from that family, who made significant contributions to the fields of science, art, religion, and local history.

Possible Linguistic Origins of the Surname

According to linguistic historian Aldo Bertoluzza, the surnames Comini and Comina are patronymics, derived from ‘Giacomino’, which a nickname of the male personal name ‘Giacomo’ (equivalent to ‘James’ in English), having the meaning ‘God has protected him’.1 If this is correct, the surnames would have the meaning ‘[the family] of Giacomo’.

As we’ll see shortly when we look at some research done by Giovanni Ciccolini, the personal name ‘Comino’ (sometimes Latinised to ‘Cominus’) also appears in earlier documents, and there does seem to be some evidence that these surnames are more directly derived from that name. However, Bertoluzza’s theory may still be accurate, as ‘Comino’ could be a shortened form of the name Giacomino, in much the same way as ‘Dorigo’ is sometimes seen as a shortened from of the name Odorico or Odorigo.

Possible Geographic Origins of the Surnames

Although Guelfi states that the Comini were indigenous to Trentino2, in Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine, authors Tabarelli de Fatis and Borelli say the Comini probably came from Valtellina in the present-day province of Sondrio, Lombardia.3 I don’t know where they obtained that information (unless it is part of the Comini family lore), but let’s explore the possibility that the Comini had Lombardian origins.

Looking at the Cognomix website, there are currently about 683 families in Italy bearing the surname Comini. Of these, 425 of these families (over 62%) live in the region of Lombardia, with the lion’s share of them (179 families) in the eastern province of Brescia, which borders Trentino. Only two Comini families currently live in the province of Sondrio. In sharp contrast to Lombardia, the region of Trentino-Alto Adige has only 23 Comini families, with only 15 of them in the province of Trento (only about 2% of the total figure). About half of these are in various comuni in Val di Sole.4

That same website tells us there are far fewer families (only about 123) with the surname Comina in Italy today. In this case, Lombardia is second on the list, with 23 families compared to 26 in Piemonte. The surname in Lombardia is sparsely distributed, with no well-defined ‘epicentre’. In Trentino-Alto Adige, there are 17 Comina families, 13 of which are in the province of Trento. Of these, the greatest number of families (albeit only 6 of them) live in the comune of Peio.5

I cannot attest to the accuracy of these figures; nor do present-day statistics always give us an accurate picture of the past. But when we consider the overall population of the region of Lombardia is currently an estimated 10 times more than that of the region of Trentino-Alto Adige,6 there appear to be almost twice as many Comini per million in Lombardia as Trentino-Alto Adige (about 42.5 compared to 23), and nearly 5 times as many Comini per million in the province of Brescia compared to the province of Trento (141 compared to 30).7 To me, these figures make a strong case for the theory of the surname’s Lombardian origins.

Do we have evidence of Lombardian immigration into Trentino occurring prior to the year 1600?

In a fascinating article from 1935,8 historian Giovanni Ciccolini shares his research into the influx of workers, craftsmen, and professionals from Lombardia into Val di Sole in Trentino from the 1301 to the end of the 1500s, arriving during an era of great economic growth owing to the burgeoning industry in iron mining.

Amongst the 155 men identified by Ciccolini, we find five referred to by the first name ‘Comino’ or its Latin equivalent ‘Cominus’, showing us the personal name was not completely uncommon in Lombardia in that era.

However, only one actually bears a surname resembling Comini or Comina, namely one ‘Cominus, son of the late Pietro de Cominis of Precasai (i.e., Prescaglio in Val Camonica)’, whose name appears in a document drafted in Peio on 24 September 1565, where he is cited as a witness.9 But we would be wrong to leap to the conclusion that this ‘Cominus’ was the patriarch of the Comina line in Peio, as other evidence shows the Comina were already living in Peio at least half a century earlier.

Thus, as interesting as Ciccolini’s research is, the records he cites neither confirm nor disprove that the Comini or Comina came from Lombardia. But if they did, some of these families HAD to have settled in Trentino no later than the late 1400s, as we can find them (but not always in an obvious way) in documents in Val di Sole by the early 1500s, with no reference to any non-Trentino place of origin.

Comini and Comina – Are they Variants of the Same Surname?

Several historians seem to make no distinction between these two surnames, but I believe this can lead to confusion. Bertoluzza puts them under the same heading in his Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino,10 but he is looking at them through the ‘lens’ of linguistics only. While these surnames may share a common linguistic root, all the evidence I have found indicates they are not genealogically related – or at least not within the past six centuries or so.

These surnames get repeatedly muddled in other sources, especially when the focus is only on one family or the other. For example, Tabarelli de Fatis and Borelli say the Comini (who were later ennobled) are documented in Ossana and Fucine in the early 1600s.11 Aside from the fact that both the Comini and the Comina were already present in Val di Sole at least a century earlier, I am fairly certain the family in Ossana and Fucine were the Comina, not the Comini.

Such confusion is probably understandable, as these surnames are often vague in early documentation. With the exception of higher nobility, surnames in general are not really used until the 1400s, and even then, they always going to be somewhat ‘fluid’ for the next few centuries. In the case of the Comini / Comina, early records will often have the truncated form ‘Comin’ or the Latinised versions ‘Cominis’ or ‘Cominus’. But by the year 1700 or so, most surnames take on a more permanent form, similar (if not identical) to how they will appear today. By this time, the distinction between Comini and Comina in Val di Sole becomes clearer:

- Comini is found predominantly in Cassana in the parish of San Giacomo.

- Comina is found predominantly in Peio, with some in nearby Ossana.

Of course, over the centuries, you will see branches of these families spreading out into other parts of the province (and beyond), but our discussion of their ‘origins’ in the province will focus mainly on these two places.

The Comina of Peio in the 1500s

Called ‘Pellium’ in Latin, Peio is a curate parish of Celledizzo, part of the decanato (deanery) of Ossana. Although there has been a church there since at least 1380, the baptismal records for Peio do not go beyond the year 1653. Peio’s death records start a few years later in 1669, and its marriages do not begin until 1811,12 although these may have been recorded in Celledizzo, where the marriages begin in 1686.13 There are some fragments of ‘urbari’ (inventories of assets, income, etc.) from first half of the 1500s and later years. One of the curates of Peio, don Giuseppe Baggia, who served there for nearly half a century, exhaustively compiled family trees and a local history of Peio. Starting his project in 1888 and continuing it until his death in 1906, he drew his information from what remained of the parish archives, after numerous fires had destroyed the bulk of its earliest records.14 Unfortunately, I have not been able to consult these trees for this current investigation.

As we have no parish registers to fall back on, we can only interpolate the history of the Comina in Peio by piecing together these fragments. This is largely what Fortunato Turrini has done in his excellent book, Carte di Peio. The first reference to a ‘Comina’ he cites is from a legal parchment dated 30 September 1516, which refers to a ‘Martino, son of Francesco Nones’.15 Parenthetically, he tells us that ‘Nones’ is actually referring to a branch of the Comina family, who presumably used ‘Nones’ as their soprannome (this is most likely drawn from the observations by don Giuseppe Baggia). If Martino is a legal adult with a father who was still alive in 1516, it would place his father Francesco’s birth date somewhere in the mid-1400s.

Drafted just few years later in 1522, we are fortunate enough to have a surviving copy of the Carta di Regola (‘Charter of Rules’) for Peio. In that document, we find the names of 38 men, representing 16 households, who have the right to participate in the meeting. Among those present, but not included among the electors, we find one ‘Martino, son of the late Francesco Nones’, as well as a ‘Pietro, called “Ganza”, son of the late Leonardo dei Nones’. Again, Turrini tells us these ‘Nones’ men are actually ‘Comina’. Later, the document does mention a ‘Martino Comina’, so it is difficult to know whether the two Martinos are the same person or two different individuals.16

Assessing the information from these documents – and trusting the accuracy of don Baggia’s assessment that ‘Nones’ is a soprannome for the family later known as Comina – we find ourselves faced with several questions:

- Were the ‘Comina’ men present at the meeting not included as electors because they were not yet full ‘citizens’ of the community?

- If so, could this indicate they had settled there within the past generation?

- If so, is there any link between these ‘Comina’ and the ‘Comino, son of the late Pietro de Cominis’ from Val Camonica we see later in the 1565 document cited by Ciccolini?

- If so, could ‘Pietro, called Ganza’ in the 1522 Carta be the father of Comino?

- Why is one Martino called ‘Comina’ and the other is not? The use of a soprannome does indicate we are dealing with more than one branch of the family, even in this early era. Do they share a common origin?

- Where did this soprannome ‘Nones’ come from? Normally this word would refer to someone from Val di Non, not Lombardia.

By the end of the 1500s, roughly two generations later, we finally find the surname ‘Comina’ firmly established in Peio. A parchment from 1580 refers to an ‘Antonio, son of the late Martino Comina’ as well as ‘Francesco, son of the late Pietro Comina’.17 Another parish in the Peio archives from 1597 mentions a ‘Francesco and Maria Comina’.18

The ‘Comin’ and Comini of Malé in the 1500s

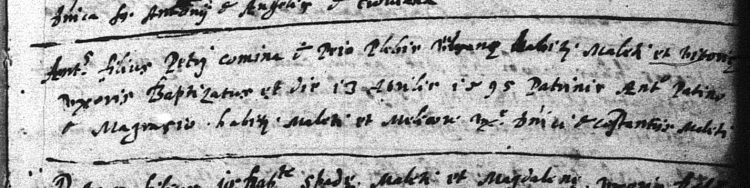

During my research, I stumbled upon a baptismal record in the parish of Malé, dated 13 April 1595, for an ‘Antonio, son of Pietro Comina of Peio in the parish of Ossana, living in Malé’.19 However, this Comina line does not seem to have continued in Malé. They are also not to be confused with Comin/Comini families who already were living in Malé before this date.

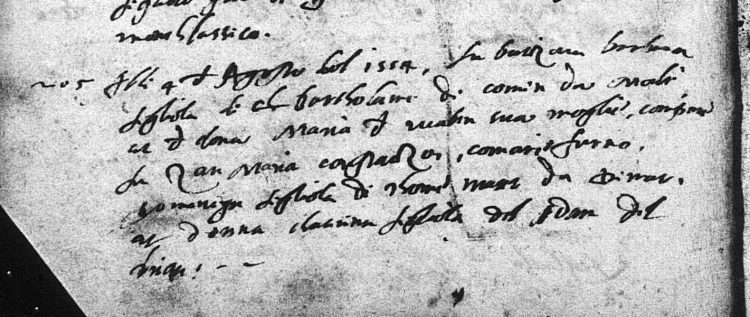

In Malé, the surname ‘Comin’ appears amongst its earliest surviving baptismal records, the first being on 4 August 1554 for a Barbara, daughter of Bartolomeo Comin of Malé and his wife, Maria20

The wording of the document infers Bartolomeo was native to Malé. As Barbara is the only child of this couple in the register, it is possible her parents were already in their 40s, which could push the birth date of Bartolomeo to around 1510, but most likely not after 1525.

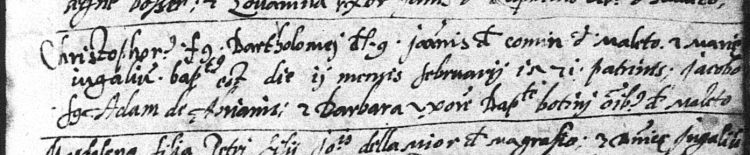

In a later Malé baptismal record for a Cristoforo Comin dated 11 February 1571, we learn his father is another Bartolomeo, son of a Giovanni, who was then deceased.21 This places the late paternal grandfather Giovanni in the same generation as the Bartolomeo seen in the previous 1554 record, meaning he was also born sometime near the beginning of that century.

Later in Malé, on 18 November 1603, we find a ‘Giovanni, son of the late Cristoforo Comini of Malé’ cited as a witness at the signing of a legal document.22 Again, we can assume Giovanni was at least 25 years of age, hence he would have been born around the same time as the Cristoforo above (so his father would have been an earlier Cristoforo). Curiously, on the same day, and written by the same notary, we find another document referring to a dom. Melchiore Comin (without the ‘i’ at the end).23

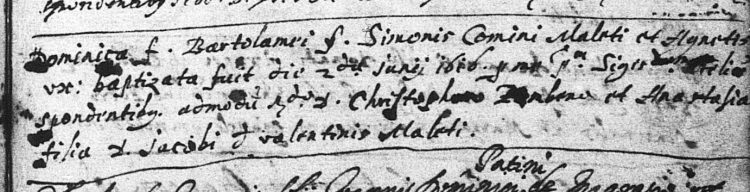

The surname seems to fade away in in Malé in the early 1600s, as the last birth I have found there is for a Domenica Comini, born 2 June 1616.24 This record gives the name of her paternal grandfather, Simone Comini, who appears to be still alive (although I cannot find a death record for him after this date). Again, the inference is Simone was native to Malé, which means he would have been born there in the mid-1500s. But apart from this baptism, I cannot find any records for this family in Malé at all (at least not in the index), nor any death records for Comini in later years.

Bartolomeo, son of Baldassare ‘Comin’ of Caldes (1551)

A legal document drafted in Terzolas (a frazione in the parish of Malé) dated 6 December 1551 mentions a ‘Bartolomeo, son of the late Baldassare “Comin” of Caldes’, who grants the use of some grazing and farming land he owns in Cassana to a Domenico Claser of Almazzago.25 Assuming Bartolomeo was a legal adult (at least 25 years old), whose father Baldassare passed away at a ‘typical’ age for this era, Baldassare was most likely born no later than the 1480s. The fact the wording says ‘of Caldes’ rather than ‘living in Caldes’, also infers Baldassare was born there. The contract is also said to have been drafted in the ‘kitchen of the home of Comini, a cobbler’; it does not give his first name, nor does it say whether he was originally from Terzolas or someplace else.

Aside from these few examples, I have found no other documents for any Comini living in Malé or Caldes in the 1500s or 1600s. Moreover, the Comini mentioned in these documents do not appear in the death records for Malé or Caldes.

However, this 1551 land agreement contains a vital clue to what happened next in the story of this particular family: the mention of the village of Cassana. From this point forward, Cassana is the place with which the Comini would become most commonly associated. Although evidence indicates that the Comini were already present in Cassana by the early decades of the 1500s, it is possible the ‘vanishing’ Comin/Comini of Malé and Caldes were part of a larger family who settled in Cassana over the next few generations.

ARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW…

The Village of Cassana in San Giacomo: Challenges of Research

Before we look specifically at the Comini, I want to explain a few things about the vital records for the village of Cassana.

These days, Cassana is part of the civil comune of Caldes; but for genealogical research, our attention will always focus on parish registers and church archives. Like most villages, Cassana has its own church, namely the little church of San Tommaso, which has long served the citizens of Cassana for Sunday Mass. However, their parish registers (births, marriages, deaths, etc.) have always been maintained by the parish of San Giacomo – originally known as ‘Solasna’, a name you will frequently see in older records.

The parish registers for Solasna/San Giacomo date back to December 1668. We know there was an earlier register that has been lost with time, from which only four pages still exist. These four pages, numbered 61, 62, 69 and 70, which have never been microfilmed or digitised, are dated between 14 May 1660 and 5 May 1668, just before the beginning of the surviving register. Given the fact these fragments start on page 61, we can imagine the lost register may have taken us back another at least 30 years, or possibly to the beginning of that century, but it’s difficult to say with certainty, as the page fragments are said to be from a book in a format smaller than the other registers.

I also checked the Livo parish records, as Livo is the ‘mother’ parish of San Giacomo, but I found no evidence of Cassana families there within that crucial timeframe.

Thus, sadly, we have to accept the fact we will not find vital records for the Comini of Cassana before 1668, which makes it difficult to construct a precise genealogical history from them. While some information can be gleaned by piecing together evidence legal parchments (pergamene) and charters (carte), these can only provide a patchwork of clues, leaving things open to much conjecture.

Despite these challenges, as I will explain shortly, I believe there is enough evidence to demonstrate there were at least two different Comini lines in Cassana, one of which arrived no later than the early 1500s, possibly directly from Lombardia as some historians have suggested. While I have excluded a connection between them and the ‘Comina’ of Peio, I am leaving an open mind as to a possible connection between the one of both of these Comini of Cassana and the early Comin / Comini of Malé and Caldes.

The Arrival of the Comini in Cassana

One thing we know with certainty is that two Comini men obtained the ‘diritto di vicinia’ of Cassana on 18 December 1603.26 The word ‘diritto’ means ‘the right’ or privilege. Cognate with our English word ‘vicinity’, the word ‘vicinia’ referred a community of people who were entitled to share in local natural resources, such as forests, water, grazing land, etc., for a specific village. Members of that community were called ‘vicini’. Only ‘vicini’ were entitled to participate in the decision-making process for the regulatory laws for the village. (Side note: the noun ‘vicini’ in modern Italian has lost this meaning; today it simply means ‘neighbours’).

The men who became vicini on this occasion were brothers Michele and Baldassare Comini, sons of the late Baldassare. Typically, residents had to have lived in a village for at least a generation before they were granted the privileges of vicini. However, this document says Michele and Baldassare were ‘living in Cassana’, implying they had moved there from someplace else.

Of course, we have no way of knowing where this ‘someplace else’ was, but we did see earlier there was a different Baldassare Comini (deceased before 1551), whose son Bartolomeo was living in Caldes, and who owned land in Cassana. Given the recurrence of the name ‘Baldassare’ (as men tended to name their eldest son after their father) and the connection to the village of Cassana, it is possible these new vicini Michele and Baldassare had an ancestral connection to the family who had previously lived in Caldes. Perhaps their father was the brother or the son of the Bartolomeo in the 1551 document.

If this was the case, it would mean the ancestors of Michele and Baldassare would have owned property in Cassana for at least half a century by 1603. This could explain why they were granted the ‘diritto di vicinia’ without having been born in Cassana. It could also explain why the Comini lines we saw in Malé and Caldes seem to have ‘vanished’ around the same time.

However, this document is NOT an indication of the Comini’s arrival in Cassana, as some historians suggest. There was, in fact, an earlier branch of the Comini already in Cassana nearly a century earlier. And, just as some historians have muddled Comina and Comini, some have also overlooked the distinction between these two Comini lines.

The key to unlocking the distinction between these Comini lines is to be found in the use of the soprannome ‘de Sera’, as we will explore next.

The Soprannome ‘de Sera’/ ‘a Sera’

Further down the page of the very same document in which Michele and Baldassare Comini receive their title of ‘vicini’ of Cassana in 1603, we find amongst the jurists one ‘Giacomo, son of Baldassare a Serra’. What would not be obvious to the casual reader is that ‘Giacomo a Serra’ is ALSO a Comini, a fact that only becomes evident when you construct a Comini family history using the parish records. But before we look at that, let’s see how ‘a Serra’ appears in documents that predate the surviving San Giacomo registers.

‘A Serra’ (more commonly seen written ‘de Sera’ or ‘a Sera’) is a soprannome. A soprannome is a kind of ‘bolt on’ name used in conjunction with (or, sometimes, instead of) the surname to distinguish one family line from others who share the surname. If you are unfamiliar with the use of soprannomi, you might wish to read an earlier article I published on this subject entitled ‘Not Just a Nickname: Understanding Your Family Soprannome’.

This particular soprannome appears in Cassana as early as 25 February 1517, with a ‘Pietro de Sera’, who is listed in a legal document as one of several ‘giurati’ (jurists) representing the village of Cassana.27 A few years later, on 17 February 1528, we see a ‘Giacomo de Sera’ mentioned as owning some property in Cassana.28

A generation later, in a legal document dated 26 March 1556, we find a ‘Marco Antonio a Sera’ referred to as the sindaco (mayor) of Cassana.29. We find this same Marco Antonio a Sera mentioned in several other documents from that same time period, 30, 31 one of which refers to him as the ‘son of the late Giacomo Dalla Sera of Cassana’, whom we might presume is the same Giacomo mentioned in 1528.32 Moving forward a decade to 3 March 1566, Marco Antonio appears to have passed away, as we find a ‘Battista, son of the late Marcantonio of Cassana’. 33

Based on these documents, we see the family who were known by the soprannome ‘de Sera’ (in whatever spelling variation) were already firmly rooted as property owners and respected vicini in Cassana by the early 1500s. In none of these documents is there any suggestion that the ‘de Sera’ had come from someplace else; moreover, to have attained the roles of giurati and sindaco in the first half of that century, they would surely have already been vicini of Cassana for a generation or more. Thus, I think it not unreasonable to hypothesise that the ‘de Sera’ were living in Cassana no later than the second half of the 1400s.

Possible Origins of the Soprannome

I am always intrigued by soprannomi, as they can often tell us something interesting about the history of a particular family line. As the soprannome ‘de Sera’ is so old, I cannot pinpoint its origins, but I do have a few theories.

My first theory is that ‘a sera’ or ‘de sera’ may be a reference to a farmland of that name in Cassana. In the document from 1566 mentioned above that mentions ‘Battista, son of the late Marcantonio of Cassana’, we see the name of a campo (a field, in this case for growing grain) called ‘a sera’.34 A century later, on 27 September 1664, we find what appears to be the same field (although this time it is called an ‘orto’, which means a vegetable garden), again called ‘a sera’.35 Thus, ‘a sera’ could have been adopted as soprannome by the family who owned and/or lived adjacent to this field.

Another possibility is that ‘Sera’ (or ‘Serra’) may be a reference to Monte Serra in Valtellina in the province of Sondrio, Lombardia. I say this mainly because Valtellina was suggested by Tabarelli de Fatis and Borelli as the place of origin of the noble Comini line, whom we will discuss shortly.36 If this is the case, the campo called ‘a sera’ may have been named after their ancestral homeland.

I can think of two other possibilities. ‘Sera’ could refer to ‘Serra’ in Val di Rabbi, or to ‘Val Seriana’ in Bergamo, Lombardia. I feel these explanations are less likely, however, as I have found no suggestion in any of my resources that the Comini had an ancestral connection to either of these places.37

The Comini de Sera of Cassana

So how do we KNOW the family known as ‘de Sera’ were actually Comini?

While the legal documents we have just discussed use the soprannome ‘de Sera’ without a surname, when you consult the births, marriages, and death records in the parish registers, you will nearly always find people in this line referred to as ‘Comini de Sera’.

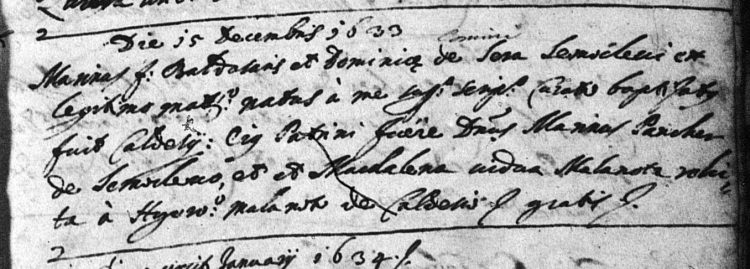

Although the surviving San Giacomo registers do not begin until 1668, I found a baptismal record dated 15 December 1633 in the parish of CALDES for a Marino, son of Baldassare Comini de Sera, who was living in Samoclevo.38

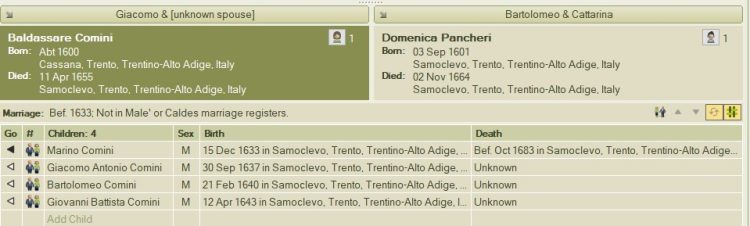

Notice that the priest originally wrote ‘de Sera’ without the surname, and either he or another priest wrote ‘Comini’ above it afterwards. All of the subsequent records for Marino’s siblings say ‘Comini’ without the soprannome. From the baptismal record of his brother Bartolomeo (born 21 February 1640), we learn that Baldassare Comini de Sera was originally from Cassana, and Baldassare’s father (who was still alive at the time) was named Giacomo. We also learn that his wife was Domenica Pancheri; she born in Samoclevo on 3 September 1601, the daughter of Bartolomeo Pancheri of Samoclevo:39, 40

I am fairly confident the father of this Baldassare is the same ‘‘Giacomo, son of (the living) Baldassare a Serra’ we saw mentioned as a jurist in Cassana in the 1603 document that granted the rights of vicinia to Michele and Baldassare Comini, who were sons of the late Baldassare.

This clearly shows us there were two distinct Comini lines present in Cassana by the year 1603:

- The older ‘Comini de Sera’ line, who were present in Cassana at least since the beginning of the 1500s.

- The more recently arrived Comini line, who did NOT use or adopt this

Whether these two lines had a common origin BEFORE the early 1500s, I cannot say. But at least from this point forward, we need to consider these as two separate families, who will nearly always be differentiated by being called either ‘Comini de Sera’ or simply ‘Comini’. This soprannome starts to disappear from legal documents around the mid-1600s, but we continue to see it in church records well into the 1700s.

ARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW…

The Comini de Sonnenberg (Comini von Sonnenberg)

Descended from the ‘Comini de Sera’ are the noble ‘Comini de Sonnenberg’, whose fame extend well beyond the province of Trentino.

We know from several sources that Michele Udalrico Comini, originally from Cassana, who was then serving as the Bishop’s Advisor and medical doctor at Bressanone, was granted imperial nobility on 27 December 1799 by Francesco II, Holy Roman Emperor.41 With this diploma, the Emperor gave Michele Udalrico the right to use the predicate ‘de Sonnenberg’, which is sometimes seen in its German equivalents ‘von Sonnenberg’ or ‘von Comini zu Sonnenberg’. Mosca says this predicate is a nod to their place of origin,42 but it surely refers to the County of Sonnenberg in the present-day state of Vorarlberg in Austria (I assume this is where they were living at the time), and not their ancient ancestral home.

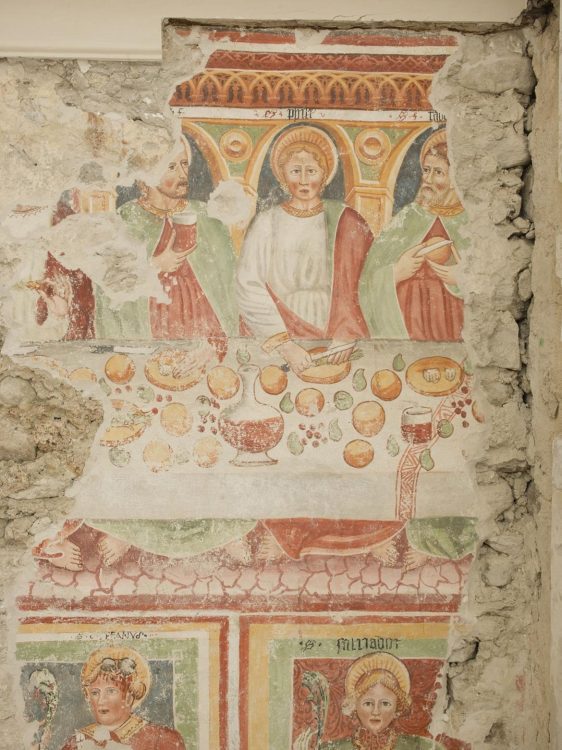

Shown here is an image of the stemma (coat-of-arms) awarded to Michele Udalrico when he was granted his noble title, as found at the Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum in Innsbruck.43 Guelfi describes stemma thusly: its shield is divided into two halves. In the top half is an eagle. In the bottom, is a dog going over a mountain; the dog is walking to the left, but his head facing to the right [his description seems to be the inverse of what is shown in the image]. This half also contains the trunk of an oak tree, bearing nuts and leaves. The crest above the shield contains two six-pointed stars.44

The Comini de Sonnenberg appear in the matriculation of Tirolesi nobility in 1827, but Tabarelli de Fatis and Borelli tell us that the line went extinct in 1877.45 I should clarify that when these authors say a line has gone extinct, they generally mean the direct male line; there may still be descendants via daughters, as females can inherit noble titles, but they cannot pass them on to their children.

Possible Discrepancy over Michele Udalrico’s Date of Birth

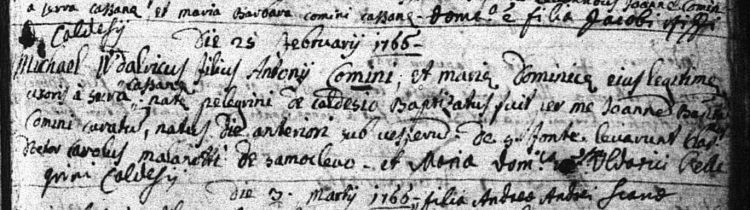

Just about any resource I have consulted says that Michele Udalrico was born in Cassana on 25 February 1766, the son of Antonio Comini ‘a Sera’ and his wife Maria Domenica Pellegrini of Caldes. Named after both grandfathers (Michele Comini ‘a Sera’ and Udalrico Pellegrini), Michele Udalrico was the third of at least 7 children born to his parents, who married in Caldes on 05 June 1758. Here is that baptismal record from the parish register of San Giacomo:46

I would have had no issue with this information had I not stumbled across this baffling document:

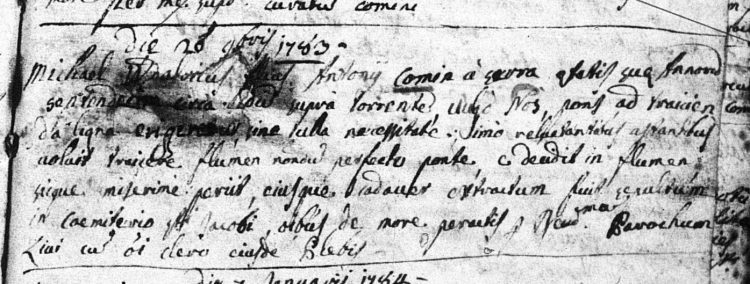

Dated 28 November 1783, this is a death record for what appears to be the same Michele Udalrico Comini a Serra, son of Antonio.47 Said to be about 17 years old (which puts his year of birth in 1766), the record says he fell off a bridge crossing a river and drowned in the river below. The boy’s body was retrieved, and he was buried in the parish cemetery. Sadly, it seems his father Antonio (actually born Giovanni Antonio) died less than a year later, on 12 August 1784, at the age of 52.48

So, now we have a problem. How could the Michele Udalrico who was born in 1766 be the man who received the noble title in 1799 if he died in 1783 when he was still in his teens? As there ARE no other boys named Michele Udalrico Comini born in this timeframe, I can only think of two explanations:

- We know Michele Udalrico had a younger brother named Udalrico who was born 18 October 1769. Perhaps the priest got the two boys mixed up in the death record, and the boy who died was actually Udalrico (who would have been only 14, not 17). There is a cross next to his name in his baptismal record, but no death record for him in infancy, so this could feasibly be the case.

- Alternatively, perhaps Michele Udalrico born in 1766 did die in 1783, and after his father died the following year, his younger brother Udalrico ‘adopted’ the name ‘Michele Udalrico’. This is a bit more far-fetched, but not impossible.

Whatever the explanation, somebody has made a mistake somewhere.

Michele Udalrico Comini de Sonnenberg

Setting aside this possible discrepancy about his date of birth, we have many documented facts about Michele Udalrico’s admirable achievements.

In his book on Caldes, historian Alberto Mosca tells us that, after completing his secondary school studies in Merano (South Tyrol), Michele Udalrico Comini first studied philosophy at Innsbruck, and then medicine at the University of Padova in Pavia, where he earned his degree in 1789. After a brief sojourn in Milan, he transferred first to Predazzo (Val di Fiemme) and then, from 1797, he was in Bressanone in the capacity of a medical doctor to the Bishop, and a student of natural philosophy. During his stay in Val di Fiemme, he published two writings, which are now conserved at the ‘Muratori’ library (library of masons) in Cavalese, on the topics of medical surgeries (1795) and on bovine epidemics in Val di Fiemme (1796).49 It was in recognition for this work that he received his noble title.

Mosca eloquently continues (my English translation from the Italian):

‘In the first years of the 19th century, Dr Michele carried out his professional activities in various parts of South Tyrol, and he published two texts in Latin on infectious diseases. He distinguished himself for the fight against epidemic illnesses; his principal merit is that of having first reported and masterfully described the disease pellagra50 in Trentino.

Before 1811, he became the Provincial Advisor of Health in Innsbruck, where he was distinguished for his administration of the hospital during the period of the Napoleonic Wars (1812-1813). In those years, in fact, the city was continually being occupied by troops, and a great many were wounded and exhausted soldiers in need of healing.

Dr Comini died in Innsbruck on 12 March 1842, after having left – in a Will drafted just one week earlier – a legacy of 200 Florins to the Church of San Tommaso in Cassana.

His ancestral house still exists, pointed out also by don Giuseppe Arvedi in 1888, in his book Illustrazione della Val di Sole, where he says, ‘In the little village of Cassana you find the lovely palazzo of the noble and celebrated Comini family’.

The Tirolrer Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum in Innsbruck has conserved a drawing that depicts Michele on his death bed.

In 2000, on the occasion of the drafting of the new road map, the administration of the comune of Caldes decided to name a street after the medico Comini in his birth village (of Cassana).’ 51

Ludwig Comini de Sonnenberg

In 1799, the same year in which he was ennobled, Michele Udalrico married the noble lady Maria Teresa Prev (I’ve also see it written ‘Prey’). Among their seven children is the celebrated scientist, Ludwig Comini de Sonnenberg.

Ludwig born in Innsbruck. Mosca says he was born in 1814, but another researcher gives us a date of 19 June 1812. 52, 53

In 1851, a blight of powdery mildew had attacked crops in South Tyrol, creating serious problems in food and wine production. Ludwig, then a pharmacist and landowner, began experimenting with sulphur, and found it to be effective in combatting this mould. After publishing his findings first in German, and then in Italian, he earned the nickname ‘Schefelapostel’, which means ‘Sulphur Apostle’.54 Many of his strategies are still widely used in farming today.

Ludwig is said to have died in Bolzano on 18 January 1869, at the age of 56.55 This photo of him was taken by an unknown photographer around 1860.56

ARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW…

Two Uncles and an Aunt: People of Interest in Michele Udalrico’s Family

In doing research for this article, I discovered many interesting facts about some of the siblings of Giovanni Antonio Comini de Sera (aka ‘Antonio’), the father of Michele Udalrico Comini de Sonnenberg.

Of these, I would like to share the stories of three of Antonio’s siblings, namely:

- Giovanni Michele Comini: born 16 November 1723, died 1753.

- Maria Cattarina Comini: born 15 December 1734, died 17 October 1799.

- Giovanni Andrea Comini: born 18 February 1741, died 29 July 1822.

Rev. Michele Comini – Priest and Artist

Born Giovanni Michele on 16 November 1723, ‘Michele’ was the eldest child of Michele Comini de Sera and Maria Cattarina Sparapani, and thus the paternal uncle of Michele Udalrico Comini de Sonnenberg.

Weber and Rasmo tell us that don Michele was a ‘very erudite man’ who studied theology in Innsbruck and became a ‘learned and pious priest’.57 During his studies, he first learned the art of making miniatures, and then he studied oil painting from Giuseppe Giorgio Grassmayr. One of Michele’s oil landscapes is in the Museum of Innsbruck. Author Quirino Bezzi tells us Michele was also a luthier (lute maker).58

A prodigy of many skills, Michele certainly accomplished a great deal within a very short time; he died in 1753, when he was not quite 30 years old. As I cannot find his death record in San Giacomo, I assume he died in Austria (most likely in Innsbruck).

The Murder of Maria Cattarina Comini de Sera

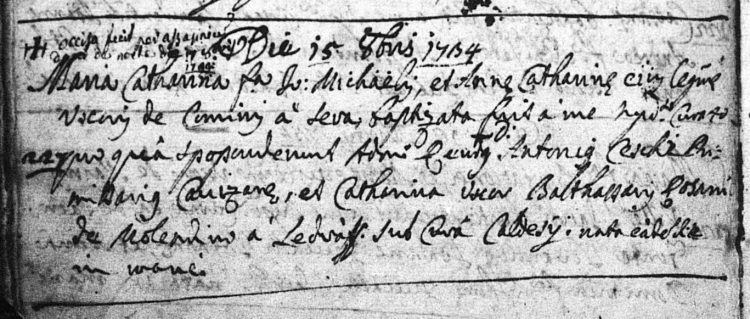

Born 15 October 1734, Antonio’s younger sister (and paternal aunt of Michele Udalrico), Maria Cattarina Comini de Sera was the sixth child of Michele Comini de Sera and Maria Cattarina Sparapani.59 When I read her baptismal record, I was shocked by a note scribbled in the upper left corner that said she was ‘killed by an assassin on 17 October 1799’:

NOTE: the priest erroneously calls her father ‘Giovanni Michele’ (it is actually just Michele) and her mother ‘Anna Cattarina’ (it is actually Maria Cattarina).

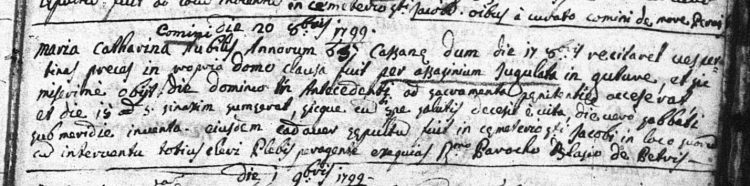

After that bombshell, I immediately looked for Maria Cattarina’s death record to see if I had read that note correctly, and also to see if it contained more details. Sadly, it was no mistake. Her death record60 explained that Maria Cattarina, age 65 and unmarried, was STRANGLED by an attacker in her own home on the night of the 17th, and then buried on the 20th:

I have not yet found any information about a trial regarding this shocking murder. Perhaps the attacker was never identified. It is a horrific thought that someone would enter the home of a 65-year-old woman (presumably alone in her bedroom, as she was unmarried) and fatally strangle her, while the rest of the village slept. What could possibly have been the provocation? Surely, there is a story here.

It is curious (although probably unrelated) that she was killed just two months before her nephew Michele Udalrico would be awarded his noble title. I cannot help but feel the award would have been bittersweet.

Rev. Giovanni Andrea Comini, parroco and deacon of Tione

Yet another uncle of Michele Udalrico Comini de Sonnenberg was Giovanni Andrea (known mainly as Andrea), born 18 February 1741. The ninth child of Michele Comini de Sera and Maria Cattarina Sparapani, he also grew up to become a Catholic priest.

At the age of 40 in 1781, he became parroco (pastor) of the parish of Tione in Val Giudicarie, where he also served as deacon/dean of its sprawling decanato (deanery) until he retired from his post in 1808.

Historian Guido Boni61 tells us that Rev. Parroco Andrea Comini contributed greatly to the local history of the parish of Tione by keeping personal manuscripts of local events, fragments of which are still held in the parish archives today. These precious manuscripts also help us learn a great deal about who Andrea was as a priest and a person. By all accounts, he seems to have been a true representative of the so-called ‘Age of Enlightenment’ into which he was born. Rational, free-thinking, progressive, and perhaps a bit of a social activist.

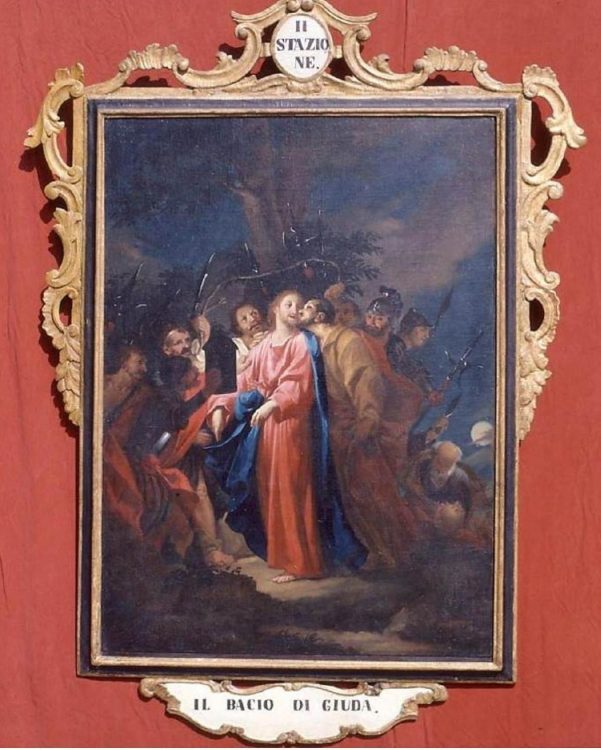

Rev. Parroco Andrea commissioned the 14 paintings of the Via Crucis (Stations of the Cross) which still adorn the parish church at Tione. Not satisfied with the prospect of these paintings depicting the traditional scenes with which most worshippers are familiar, don Andrea wanted them to illustrate the ‘painful’ moments before Jesus’s ascent up Calvary. His vision helped direct a set of paintings (the first seven of which are attributed to Prospero Schiavi of Verona) that are renowned for their uniqueness and uncommon ‘take’ on the subject of the Crucifixion.62 Boni tells us that don Andrea also wrote a booklet of prayers to be said at each of these stations, but he did not obtain the approval of the Curia to publish them.63 Perhaps they were considered too progressive or emotive, rather than humble and reverential?

Early in his time as parroco, Andrea Comini was involved in a ‘clamorous incident’ with a spinster named Domenica Benvenuti, who claimed to live without eating, and who had managed to gather a large following of people who venerated her as saint. And if that were not bad enough, her devotees would also give her money. Boni tells us that don Andrea ‘bravely faced the popular fanaticism that had taken possession of even the men of science’ and unmasked the woman as a fraud. Furious at her defeat and disgraced in the public eye, the woman withdrew to a hospital in the city of Trento, where she died in 1785. 64

His service to his community extended beyond the boundaries of theology, however. Boni tells us that don Andrea had a waterwheel built, and also had a well dug (but they failed to find any water due to the local terrain). He surrounded the rectory with walls and built a ‘roccolo’, which is a kind of structure once used in the mountains for catching birds (the practice is no longer permitted). The locality where it stood, at least during Boni’s time in the 1930s, was still called ‘The rocol of the Archpriest’ by locals.

During the Festival of the Rosary in 1787, don Andrea had a nasty surprise when the beautifully crafted silver lamp from the altar was stolen, along with some other objects. The thieves had used tools to break into the northern door of the church, which faced the countryside, making it possible for them to rob the church without anyone seeing them in the act. In his manuscript, Rev. Comini advises his successors not to spare the expense of getting maintaining a good watchdog!

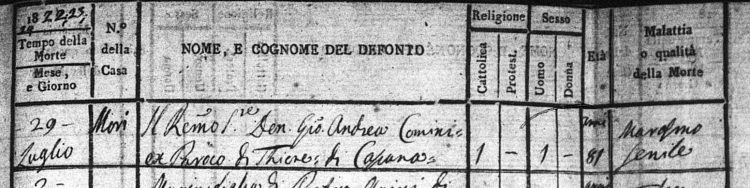

In the autumn of 1808, when he was 66 years of age, don Andrea gave up his job as parroco and deacon, presumably to retire and live a more peaceful life. At some point, he returned to his native parish of San Giacomo, where he died on 29 July 1822, at the age of 81. The cause of death is said to be ‘marasmo senile’, which was, in those days, a catch-all term for ‘old age’, rather than any specific illness. In the record, he is still referred to as ‘the Parroco of Tione’, despite having retired some 14 years earlier.65

Conclusions and Closing Thoughts

I began this article with a discussion of the linguistic and geographical origins of the surname Comini, and the similar surname Comina. Although I have found no documented evidence that the Comini of Cassana came from Lombardia as some have suggested, we do see the surname being most prominent in the region of Lombardia today. And, although I have found no patriarch bearing the name ‘Giacomino’ as Bertoluzza suggests, we did see that the personal name ‘Comino’ was apparently in use, at least in Lombardia, in the 1400s. As an historian, I can only conclude at this point that it is ‘feasible’ the Comini may have from Lombardia at some point, and that the identity of the specific patriarch from whom their surname was originally derived has been lost in antiquity.

Using early legal documents and some available parish records, I then demonstrated that the Comina and Comini are not the same surname, and that these families are unrelated (or at least not within traceable history). We also looked at some earlier appearances of the surname in the parishes of Malé and Caldes.

Next, we moved on to discuss the Comini of Cassana, noting how there were actually two separate Comini families:

- the older line (in Cassana from at least the 1400s), known by the soprannome ‘de Sera’ / ‘a Sera’, from which arose the famed ‘Comini de Sonnenberg’ family, and

- the Comini who were granted the right of vicinia in 1603, who did not use this

While it is certainly possible these two lines had an ancient familial connection before the arrival of the ‘de Sera’ line in Cassana, as family historians, we must take care not to confound these two lines in our research.

After discussing the noble title of Michel Udalrico Comini de Sonnenberg, I shared a few short biographies of members of the ‘de Sera’ and ‘de Sonnenberg’ lines, which I felt were either historically significant or simply interesting. Genealogy becomes merely an academic exercise without at least a few personal stories from the past.

Like any other family, branches of the Comini migrated beyond their ‘home base’ over the centuries. If you search for the surname ‘Comini’ on the Nati in Trentino website, which shows births in Trentino between 1815-1923, you will find Comini living in other parishes besides San Giacomo. But when you dig more deeply, you will find many (if not most) of these lines will eventually lead back to the Comini of Cassana.66 Thus, becoming well-acquainted with the available records, surnames and soprannomi of the parish of San Giacomo are paramount when researching this family.

Lack of early parish records (including a lost register from the early 1600s), and the patchiness of available legal documents, are two of the unavoidable handicaps that genealogists and local historians must work around when researching the Comini. In light of these handicaps, I wish to stress that I am prepared to say ‘I don’t know the answer’ to some of the questions presented in this article. Too many mistakes persist when historians simply accept ‘facts’ from past research as ‘true’ without cross-checking the evidence. I believe it is the responsibility of any good historian to accept ambiguity as part of the picture, rather than try to make things ‘fit’ because we are uncomfortable with the unknown.

No history, including family history, is ever completely and indisputably ‘true’. While some things may be provable enough to accept them as ‘probably true’, most will be open to some degree of interpretation. Thus, all we can do is keep looking, learning, and trying to understand the distant echoes of the past, through whatever fragments of evidence our ancestors may have left behind.

======

This research is part of a book in progress entitled Guide to Trentino Surnames for Genealogists and Family Historians. I hope you follow me on the journey as I research and write this book; it will probably be a few years before it comes out, and it is likely to end up being a multi-volume set.

If you liked this article and would like to receive future articles from Trentino Genealogy, be sure to subscribe to this blog using the form below.

Until next time!

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

30 October 2021

P.S. I have finally booked a trip to Trento for February-March 2022, but my client roster filled up for that trip in less than 8 hours!

THE GOOD NEWS IS: I have MANY resources for research here in my home library, and I am able to do research for many clients without having to travel to Trento. My client roster is fully booked through the January 2022, but I am now taking bookings for spring 2022.

If you would like to book a time to discuss having me do research for you, I invite you to read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, we can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://trentinogenealogy.com/my-tree/

REFERENCES

-

- BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino. Trento: Società Iniziative Editoriali (S.R.L.)., page 95.

- GUELFI, Adriano Camaiani. 1964. Famiglie nobili del Trentino. Genova: Studio Araldico di Genova, page 39.

- TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 93.

- Comini. Accessed 21 October 2021 from https://www.cognomix.it/mappe-dei-cognomi-italiani/COMINI.

- Comina. Accessed 21 October 2021 from https://www.cognomix.it/mappe-dei-cognomi-italiani/COMINA.

- CITY POPULATION. Population for regions of Lombardia and Trentino-Alto Adige. Accessed 29 October 2021 from https://www.citypopulation.de/en/italy/admin/03__lombardia/ and https://www.citypopulation.de/en/italy/trentinoaltoadige/

- ‘Province of Brescia’. Reported population of the province of Brescia was 1,265,964 as of January 2019. ‘Trentino’. Reported population of province of Trentino of 541,098 in 2019. Accessed 26 October 2021 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Province_of_Brescia and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trentino.

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1935. ‘Immigrati lombardi in Val di Sole nei secoli XIV, XV e XVI’. Archivio Storico Lombardo: Giornale della società storica lombarda (1935 dic, Serie 7, Fascicolo 2- 3 e 4), pages 376-432. Accessed 20 October 2021 from http://emeroteca.braidense.it/eva/sfoglia_articolo.php?IDTestata=26&CodScheda=113&CodVolume=801&CodFascicolo=2148&CodArticolo=61692 .

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni, ‘Immigrati’, page 428. ‘Precasai’ refers to Precasaglio, which is a frazione in the comune of Ponte di Legno, in upper Val Camonica, in the province of Brescia.

- BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998, page 95.

- TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005, page 93.

- CASETTI, Albino. 1951. Guida Storico – Archivistica del Trento. Trento: Tipografia Editrice Temi (S.R.L.). page 524.

- CASETTI, Albino. 1951, page 200.

- COOPERATIVA KOINÈ. 2004. Parrocchia di San Giorgio in Peio. Inventario dell’archivio storico (1409 – 1953) e degli archivi aggregati (1458 – 1973). Provincia autonoma di Trento. Soprintendenza per i Beni librari e archivistici. Page 6, 34.

- TURRINI, Fortunato. 1996. Carte di Peio. Centro Studi per la Val di Sole. Pergamena number 646 dated 30 September 1516, cited on page 153.

- TURRINI, Fortunato, pages 157-162. In the Section on the Carta di Regola of 1522.

- TURRINI, Fortunato, page 155. Pergamena n. 199 in Peio on 9 January 1580.

- TURRINI, Fortunato, page 157. Pergamena n. 209 in Peio on 10 September 1597.

- Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 10. 13 April 1595: Baptism of Antonio, son of Pietro Comina of Peio in the parish of Ossana, living in Malé.

- Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 15. 4 August 1554: Baptism of Barbara, daughter of Bartolomeo Comin of Malé.

- Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 115. 11 February 1571: Baptism of Cristoforo, son Bartolomeo, son of Giovanni Comin of Malé.

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1939. Inventari e Regesti degli Archivi Parrocchiali della Val di Sole. Volume 2: La pieve di Malé. Trento: Temi-Tipografia Editrice. Page 185, regesto: n. 180.

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1939. Volume 2, Malé, page 186, regesto: n. 181.

- Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 132. 2 June 1616: Baptism of Domenica, daughter of Bartolomeo, son of Simone Comini of Malé.

- PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Costituzione di senso, 6 December 1551, Terzolas’. Bartolomeo, son of the late Baldassare “Comin” of Caldes’ grants the use of some grazing and farming land he owns in Cassana to a Domenico Claser of Almazzago. Archivi Storici del Trentino. Accessed 9 October 2021 from https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/50274.

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1965 (reprint). Inventari e Regesti degli Archivi Parrocchiali della Val di Sole. Volume 3: La Pieve di Livo. Page 92, pergamena 184.

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1965. Volume 3, Livo, page 75, pergamena 134.

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1965. Volume 3, Livo, page 76-77, pergamena 140. The document does not directly deal with Giacomo, but it mentions his property as being adjacent to another under discussion.

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1965. Volume 3, Livo, page 81, pergamena 151.

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1965. Volume 3, Livo, page 81, pergamena 152. Cites Marco Antonio a Sera when he provides an estimate for a piece of land in Cassana, 5 December 1557.

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1965. Volume 3, Livo, page 82-83, pergamena 156. Marco Antonio a Sera mentioned as owning property adjacent to another being sold on 29 January 1559.

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1965. Volume 3, Livo, page 82, pergamena 154. Marco Antonio, son of the late Giacomo Dalla Sera of Cassana shown as paying a debt on 18 April 1558.

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1965. Volume 3, Livo, page 84, pergamena 161.

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1965. Volume 3, Livo, page 84, pergamena 161.

- CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1965. Volume 3, Livo, page 95, pergamena 193.

- TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005, page 93.

- PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Cessione a soluzione di debito, 16 October 1542, Castel Caldes’. In this document, there is a blacksmith Mag. Giovanni Antonio, son of the late Giacomo, originally from Val Seriana in the bishopric of Bergamo, living in Cassana, selling a house. One could go out on a limb and conjecture that said ‘Giacomo’ becomes ‘Giacomini’ and then ‘Comini’, but the timing is off, as the ‘a Sera’ line was already in Cassana for at least 40 years by this point. Archivi Storici del Trentino. Accessed 22 October 2021 from https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/49984 .

- Caldes parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 80-81. 15 December 1633. Baptism of Marino, son of Baldassare Comini de Sera (living in) Samoclevo.

- Malé parish records, baptisms, volume 2, page 54. 3 September 1601, baptism of Domenica Pancheri of Samoclevo, daughter of Bartolomeo and Cattarina.

- This is a screenshot from a family tree I have constructed using Family Tree Maker software.

- TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005, page 93. Tabarelli de Fatis, page 93] Note that the initials ‘S.R.I.’ are often used to indicate imperial nobility. The initials stand for ‘Sacro Romano Impero’, i.e., Holy Roman Empire.

- MOSCA, Alberto. 2015. Caldes: Storia di Una Nobile Comunità. Pergine Valsugana (Trentino, Italy): Nitida Immagine Editrice. Page 271.

- TYROLEAN COAT OF ARMS. The Fischnal coat of arms index. ‘Comini.’ Innsbruck: Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum. Accessed 24 October 2021 at https://wappen.tiroler-landesmuseen.at/index34a.php?id=&do=&wappen_id=7185

- GUELFI, Adriano Camaiani. 1964, page 39.

- TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005, page 93.

- San Giacomo parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 106. 25 February 1766. Baptism of Michele Udalrico Comini ‘a Sera’ of Cassana.

- San Giacomo parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number. 28 Nov 1783. Death record of Michele Udalrico Comini a Serra, who drowned at age 17.

- San Giacomo parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number. 12 Aug 1784, death record of Antonio Comini de Serra.

- MOSCA, Alberto. 2015, page 271-272.

- Pellagra was an often-fatal disease running rampant in Trentino in the 18th and 19th Arising from a severe niacin deficiency, it was typically caused by a diet lacking in diversity, which was too dependent upon corn (corn that is not first cut with lime can leach niacin from the body). For more information on this disease, I recommend the book A Plague of Corn by Daphne Roe.

- MOSCA, Alberto. 2015, page 271-272.

- MOSCA, Alberto. 2015, page 271-272.

- CASSIGOLI, Andrea. ‘Ludwig von Comini zu Sonnenberg’. Geni website. Accessed 18 October 2021 from https://www.geni.com/people/Ludwig-von-Comini-zu-Sonnenberg/6000000090531034210.

- ‘Ludwig von Comini’. Accessed 18 October 2021 from https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludwig_von_Comini

- CASSIGOLI, Andrea. ‘Ludwig von Comini zu Sonnenberg’.

- Photo of Ludwig Comini von Sonnenberg taken around 1860 by an unknown photographer. Public domain. Accessed 18 October 2021 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30588371

- WEBER, Simone; RASMO, Nicolò. 1977. Artisti Trentini e Artisti Che Operarono Nel Trentino. Trento: Monauni. Originally published in 1933, this is the 2nd edition. Page 104.

- BEZZI, Quirino. 1975. La Val di Sole. Malè (Trentino): Centro Studi per la Val di Sole. Page 271.

- San Giacomo parish records, baptisms, volume 1, page 82. 15 October 1734. Baptismal record of Maria Cattarina Comini de Sera. Note that the record erroneously calls her father ‘Giovanni Michele’ and her mother ‘Anna Cattarina’. The note about her murder is written in the upper left corner.

- San Giacomo parish records, deaths, volume 1, no page number. 20 October 1799. Death record of Maria Cattarina Comini de Sera, who was strangled in her own home.

- BONI, Guido. 1937. ‘Origini e memorie della chiesa plebana di Tione’. Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, 1937-1938. Boni’s paper is spread out across four issues of the magazine. Part 3 accessed 20 October 2021 from http://pressviewpat.immanens.com/it/pvPageH5B.asp?skin=pvw&puc=002017&pa=306&nu=1938#292 and Part 4 from http://pressviewpat.immanens.com/it/pvPageH5B.asp?skin=pvw&puc=002017&pa=306&nu=1938#292

- PARROCCHIA TIONE DI TRENTO. ‘La Nostra Storia e del Nostro Paese’. Accessed 25 October 2021 from http://www.parrocchiationeditrento.it/2013/12/la-nostra-storia-e-del-nostro-paese.html

- BONI, Guido. 1937. Part 3, page 193.

- BONI, Guido. 1937. Part 4, page 263-264. All of the following anecdotes are from these pages.

- San Giacomo parish records, deaths, volume 2, no page number. 29 July 1822. Death of Rev Giovanni Andrea Comini, former parroco of Tione.

- For example, Vigilio Antonio Comini, who was born in Cis on 26 July 1841 was the son of Antonio Comini from Cassana (Cis parish records, baptisms, volume 3, page 39); Grazioso Tommaso Comini born in Livo on 10 December 1907 was the son of Silvio Comini of Cassana (Livo parish records, baptisms, volume 5, page 144).

RESOURCES

NOTE: In addition to the resources listed below, I also utilised the parish registers for San Giacomo, Malé, Caldes, Livo, and Cis.

BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino. Trento: Società Iniziative Editoriali (S.R.L.).

BEZZI, Quirino. 1975. La Val di Sole. Malè (Trentino): Centro Studi per la Val di Sole.

BONI, Guido. 1937. ‘Origini e memorie della chiesa plebana di Tione’. Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, 1937-1938. Boni’s paper is spread out across four issues of the magazine. Part 3 accessed 20 October 2021 from http://pressviewpat.immanens.com/it/pvPageH5B.asp?skin=pvw&puc=002017&pa=306&nu=1938#292 and Part 4 from http://pressviewpat.immanens.com/it/pvPageH5B.asp?skin=pvw&puc=002017&pa=306&nu=1938#292

CASETTI, Albino. 1951. Guida Storico – Archivistica del Trento. Trento: Tipografia Editrice Temi (S.R.L.).

CASSIGOLI, Andrea. ‘Ludwig von Comini zu Sonnenberg’. Geni website. Accessed 18 October 2021 from https://www.geni.com/people/Ludwig-von-Comini-zu-Sonnenberg/6000000090531034210.

COGNOMIX. Comina. Accessed 21 October 2021 from https://www.cognomix.it/mappe-dei-cognomi-italiani/COMINA.

COGNOMIX. Comini. Accessed 21 October 2021 from https://www.cognomix.it/mappe-dei-cognomi-italiani/COMINI.

CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1935. ‘Immigrati lombardi in Val di Sole nei secoli XIV, XV e XVI’. Archivio Storico Lombardo: Giornale della società storica lombarda (1935 dic, Serie 7, Fascicolo 2- 3 e 4), pages 378-432. Accessed 20 October 2021 from http://emeroteca.braidense.it/eva/sfoglia_articolo.php?IDTestata=26&CodScheda=113&CodVolume=801&CodFascicolo=2148&CodArticolo=61692 .

CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1939. Inventari e Regesti degli Archivi Parrocchiali della Val di Sole. Volume 2: La pieve di Malé. Trento: Temi-Tipografia Editrice.

CICCOLINI, Giovanni. 1965 (reprint). Inventari e Regesti degli Archivi Parrocchiali della Val di Sole. Volume 3: La Pieve di Livo. Trento: Temi-Tipografia Editrice.

COOPERATIVA KOINÈ. 2004. Parrocchia di San Giorgio in Peio. Inventario dell’archivio storico (1409 – 1953) e degli archivi aggregati (1458 – 1973). Provincia autonoma di Trento. Soprintendenza per i Beni librari e archivistici.

CULTURA TRENTINO. ‘Gli affreschi ritrovati nella chiesa di S. Tommaso a Cassana.’ Photos of restored frescos in the Church of San Tommaso in Cassana. Accessed 20 October 2021 from https://www.cultura.trentino.it/Rubriche/Restauri-in-evidenza-fra-pubblico-e-privato/Gli-affreschi-ritrovati-nella-chiesa-di-S.-Tommaso-a-Cassana

GUELFI, Adriano Camaiani. 1964. Famiglie nobili del Trentino. Genova: Studio Araldico di Genova.

MOSCA, Alberto. 2015. Caldes: Storia di Una Nobile Comunità. Pergine Valsugana (Trentino, Italy): Nitida Immagine Editrice.

PARROCCHIA TIONE DI TRENTO. ‘La Nostra Storia e del Nostro Paese’. Accessed 25 October 2021 from http://www.parrocchiationeditrento.it/2013/12/la-nostra-storia-e-del-nostro-paese.html

PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Cessione a soluzione di debito, 16 October 1542, Castel Caldes’. Accessed 22 October 2021 from https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/49984 .

PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Costituzione di senso, 6 December 1551, Terzolas’. Archivi Storici del Trentino. Accessed 9 October 2021 from https://www.cultura.trentino.it/archivistorici/unita/50274.

PROVINCIA AUTONOMA DI TRENTO. ‘Nati in Trentino’. Online database of Trentino births between 1815-1923. Accessed from https://www.natitrentino.mondotrentino.net/

STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino.

STENICO, P. Remo. 2000. Sacerdoti della Diocesi di Trento dalla sua Esistenza Fino all’Anno 2000.

TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche.

TRENTINO CULTURA. ‘Gli affreschi ritrovati nella chiesa di S. Tommaso a Cassana’. Accessed 12 October 2021 from https://www.cultura.trentino.it/Rubriche/Restauri-in-evidenza-fra-pubblico-e-privato/Gli-affreschi-ritrovati-nella-chiesa-di-S.-Tommaso-a-Cassana

TURRINI, Fortunato. 1996. Carte di Peio. Centro Studi per la Val di Sole.

TYROLEAN COAT OF ARMS. The Fischnal coat of arms index. ‘Comini.’ Innsbruck: Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum. Accessed 24 October 2021 at https://wappen.tiroler-landesmuseen.at/index34a.php?id=&do=&wappen_id=7185

WEBER, Simone; RASMO, Nicolò. 1977. Artisti Trentini e Artisti Che Operarono Nel Trentino. Trento: Monauni. Originally published in 1933, this is the 2nd edition.

WIKIMEDIA. Photo of Ludwig Comini von Sonnenberg taken around 1860 by an unknown photographer. Public domain. Accessed 18 October 2021 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30588371

WIKIPEDIA. ‘Province of Brescia’. Accessed 26 October 2021 at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Province_of_Brescia.

WIKIPEDIA. ‘Trentino’. Accessed 26 October 2021 at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trentino.