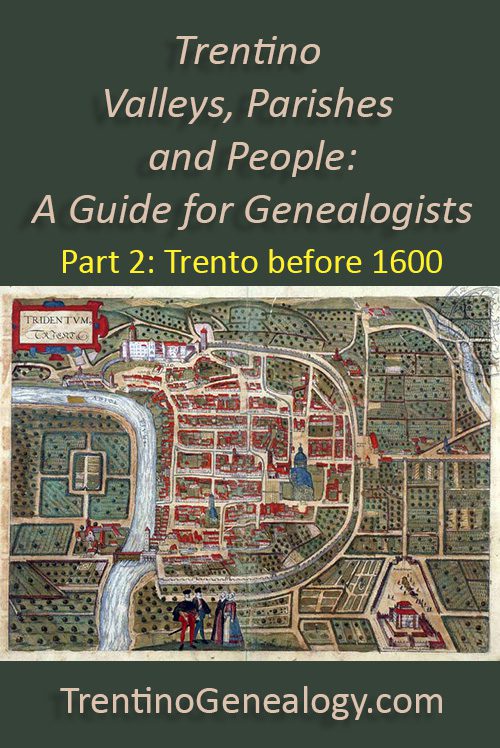

The people and surnames of the city of Trento before the year 1600. Part 2 of ‘Trentino Valleys, Parishes and People: A Guide for Genealogists’ by Lynn Serafinn.

Last time, in Part 1 in this special series on Trentino valleys, I gave you an overview of the CIVIL and CHURCH structures in Italy, as well as the VALLEYS in the Province of Trentino (sometimes called the Province of Trento). We also explored the political history of the province, looked at the former office of the PRINCE BISHOP of Trento, and discussed how the Catholic Church has been the most stable institution in Trentino throughout the centuries.

If you haven’t read that article, or if you are unfamiliar with these topics, I invite you to check it out at https://trentinogenealogy.com/2020/01/trentino-valley-parishes-guide/

What We’ll Look at Today

Today, I want to start a detailed discussion on the CITY of Trento. As there is a lot of material to cover, I have split the subject into 3 different articles:

- In TODAY’S ARTICLE, we’ll look at Trento before the year 1600, including a bit of history and an interesting examination of the SURNAMES present in the city up to that year.

- In the next article, we’ll look at Trento in the 19th century, including its population, surnames, occupations and other demographics. We’ll also look at how the city is divided into various municipalities (comuni).

- Then, in the article to follow, we’ll look at the PARISHES that come under the DECANATO (deanery) of Trento, and the records that are available for research in each.

Getting Oriented – Trentino vs Trento

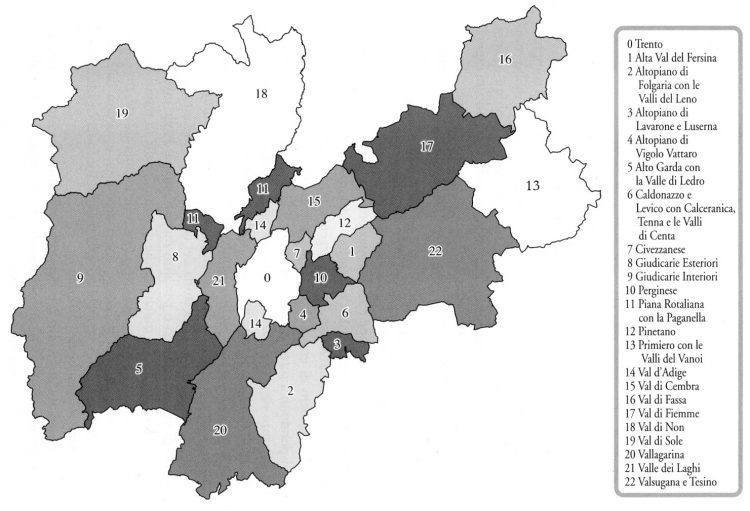

Last time, I shared a map with you from the book Toponomastica Trentina: I Nomi delle Località Abitate by Giulia Maistrelli Anzilotti, in which she organised the province of Trentino into 23 areas, largely defined by their valleys:

Click on map to see it larger

If you look closely at the map, you’ll see there’s a big ZERO in the centre, which refers to the greater metropolitan area of the CITY OF TRENTO:

I’ve chosen the city of Trento as our starting point as we explore the province for these important reasons:

- Many beginning researchers CONFUSE the city itself with the PROVINCE; I would like to highlight how it is different.

- Many descendants of Trentino emigrants are LESS FAMILIAR with the city of Trento than with their specific ancestral parishes. This is surely because the vast majority of those who immigrated from the province in the late 19th and early 20th centuries came from RURAL valleys.

- The city of Trento was a HUGELY important religious, political and cultural influence in our ancestors’ lives – even those who lived in the most rural parts of the province.

A Snapshot of Trento Before 1600

Situated on the River Adige in Val D’Adige, the area we know as Trento has been settled for thousands of years. Originally home of the Rhaetian people and other tribes, the ROMANS also loved Trento, calling it ‘Tridentum’, meaning ‘three teeth’, referring to the three mountain peaks within which the city is situated. In fact, beneath the present-day city can visit the ruins of the ancient streets and homes dating back to the Roman era.

During the medieval era, Trento blossomed into a cathedral city – the seat of the Bishopric of Trento. There was once a quarry on the north side of the city, which was the source of the distinctive pink and white stone that was used for pavement and flooring in every part of that medieval city. From the floors in the Duomo of San Vigilio, to those in the magnificent Castello del Buonconsiglio, to the city streets themselves, to the ‘Tre Portoni’ archways leading to Palazzo delle Albere, you will see these pink and white stones everywhere. If you look closely at this stone, you will notice the fossils of ammonites, indicating this entire area had been under the sea many millions of year ago.

When I first started looking at old maps of Trento (such as the one in the image at the top of this page), I was baffled because the River Adige seemed to curve around and ‘embrace’ the city in such a way that it does not do today. I also knew from historical source that the 12th century Badia di San Lorenzo (Abbey of Saint Anthony) – which is now just a short walk from Trento railway station – was originally built on the opposite bank of the River Adige, away from the rest of the city. But according to an article published in Journal of Maps in 2018, ‘the Adige River was subjected to massive channelisation works during the nineteenth century, to ensure flood protection, to reclaim agricultural land, and to facilitate navigation and terrestrial transportation.’ Thus, the layout of the city today is not exactly how most of our ancestors would have seen in it the past.

Historically, Trento is perhaps most famous as the site of the Concilio di Trento (Council of Trento), which took place in the mid-1500s. The Council of Trento was an especially significant event to us as genealogists, as it was here that the keeping of parish registers was mandated by the Catholic Church.

If you want to find out more about the Concilio di Trento, I refer you to this video of one my past ‘Filò Friday’ podcasts, where I talk about the council in some detail – including how the managed to fit thousands of delegates and their servants into a relatively small urban centre:

CIVIL RECORDS – Libro della Cittadinanza di Trento (1577)

One of the first things many family historians do when starting their family tree is look for census records. From these, we can get a snapshot of family groups and their neighbourhoods, often learning names, ages, places of birth, occupation, date of immigration (especially in US docs), etc.

Early forms of census records (although they weren’t called this) existed in Trentino, but rarely did they look like the kind of census records with which we are familiar today. With specific reference to the city of Trento, one good example is the Libro della Cittadinanza (Citizenship Book of Trento), written in 1577 – only a few years after the Concilio di Trento (Council of Trento).

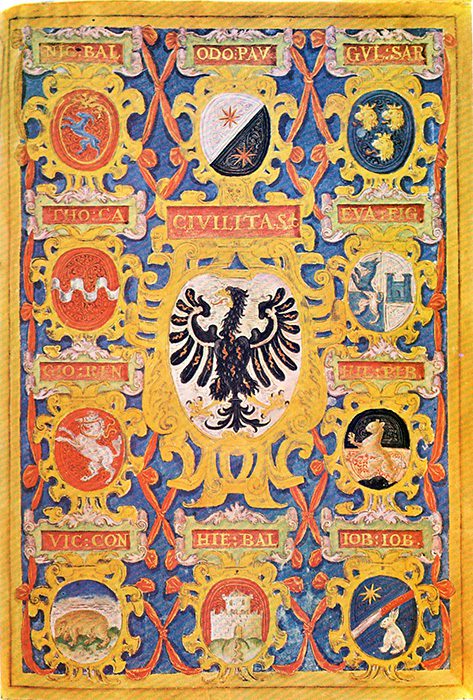

Below is an image of the original cover, with its metal cornices:

NOTE: Before I continue, I should mention that all the images and information I have gleaned about the 1577 Libro della Cittadinanza has been taken Aldo Bertoluzza’s work Libro della Cittadinanza di Trento: Storia e tradizione del cognome Trentino (Citizenship Book of Trento: History and tradition of the surnames of Trentino), published in 1975.

NOTE: Before I continue, I should mention that all the images and information I have gleaned about the 1577 Libro della Cittadinanza has been taken Aldo Bertoluzza’s work Libro della Cittadinanza di Trento: Storia e tradizione del cognome Trentino (Citizenship Book of Trento: History and tradition of the surnames of Trentino), published in 1975.

Compiled by a specially selected panel consuls, the purpose of the 1577 Libro della Cittadinanza was to create an official register of the ‘citizens’ of the city of Trento.

Page 1 of the book, printed on parchment, and decorated in gold, is a fascinating piece of art showing the stemmi (crests / coats-of-arms) of these 10 consuls. In the centre is the famous L‘Aquila di S. Venceslao (Eagle of San Wenceslaus), which has been the stemma, and indeed the symbol, of the province of Trento since 1339:

For the sake of the artwork, the names of the 10 consuls are abbreviated, but they are spelled out on page 2 of the book. Here they are from top to bottom and left to right:

-

- NIC : BAL = His Excellency Dr Nicolo’ Balduino

- ODO : PAU = His Excellency Dr Odorico Paurenfaint

- GUI : SAR = Guglielmo Saracino

- THO : CA = Thomio Cazuffo

- EVA : FIG = Evangelista Figino

- GIO : REN = His Excellency Dr Giovanni Rener

- HIL : PI = Hiliprando Piber

- VIC : CON = Vincenzo Consola, Attorney

- HIE : BALD = Hieronimo Baldirone, Collector

- IOB : IOB = Iob de Iob, Councillor

The Idea of ‘Citizenship’

The consuls expressed the desire to bring back the original concept of ‘citizenship’ as it had been perceived by the ancient Romans, i.e. that it was not a title given to anyone who decided to live in the city, but to those who actively contributed to the welfare of the city in some way. Thus, criminals or vagrants (they mention murders, etc.) could not be ‘citizens’; nor could people who had only recently moved to the city or who were just passing through.

They also said ‘stranieri’ (foreigners) could not qualify as citizens, a word that makes me raise my eyebrows. ‘Stranieri’ could be a long-term label, linked to ethnicity. In other words, a family of a race/ethnic group who were socially deemed as ‘outsiders’ could have been living in the city for centuries, but never given the privilege of citizenship. I haven’t looked into what this definition meant specifically in Trento (so I don’t want to make any suggestions), but it certainly makes me curious.

With those guidelines in mind, the Council decided to collate and organise data from earlier documents (one from 1528 and others from the 1400s), that listed the families who had owned property in the city of Trento, and then combine this information with the names of those who had purchased property in the city since those dates. The idea was that any time someone bought property (including ‘tavernas’ or other places where guests could stay) they would be added organically to the list, thus keeping an ongoing picture of the so-called ‘citizens’ of the city.

Once the initial book was completed, they declared this ‘Citizenship Book’ would forever be faithfully guarded by the City Council, and that anyone who was not listed in the book would not be entitled to any benefit or privilege of the city.

Thus, while historically fascinating, from a genealogical perspective, the Libro della Cittadinanza cannot be seen as a ‘census’ in the true sense of the word, as it doesn’t give us the full picture of the population of the city.

Some Trento Surnames Before 1577

On pages 16-23 of Bertoluzza’s book from 1975, he lists ALL the names from the 1577 Libro della Cittadinanza di Trento. As there are hundreds of names, I cannot possibly list them here; moreover, it is difficult to ‘scan’ through them, as they were entered as and when new landowners were recorded.

Here’s a random sampling of some of the surnames that were obviously entered from pre-1577 entries:

Alberti, Alessandrina, Approvina, Balduino, Banali, Berlina, Betta of Arco, Bomporta, Bona, Brunora, Caleppina, Calvetto, Cazuffa, Chiusola, Colomba, Del Libera, Galla, Gaudenta, Gelpha, Gentilotta, Gratiadea, Guarienta of Rallo, Hibinger, Hilipranda, Hilti, Ianona, Lodron, (the family of Casa) Marazzona, Marchetti of Cadene, Mathioli, Mazzola, Micheletta, Mirana, Morella, Mozzatti, Nigra called ‘Usbalda’, The Family of Paho, Paurinfaint, Ponchina, Pratta, Pronsteter, Raino, Rochabruna, Romagnana, Rovereta, Saracina, Serena, Sizza, Sratimpergera, Tabarella, Ticina, Tiler, Tonello of Vezzano, Toner, Trilacha, Worema, Zello.

It is important to bear in mind that standardised spelling was simply NOT a consideration until the 20th century. And, when you also consider the fact that formal surnames really had only come into common practice around the 1400s, we might begin to understand why these surnames might look so unfamiliar to us. Names were usually written phonetically, according to how the person recording the record heard it, which surely explains why so many Germanic names are spelled weirdly by Italian-speaking priests.

But even when working solely within Italianate surnames, there are a number of permutations you are likely to see from one record to another:

-

- Final vowels might differ.

- Internal vowels might differ.

- Double/single consonants might differ.

These permutations in older records do NOT signify a different surname as they might today. Some of the names in the above list might look more familiar if we apply these permutations ‘rules’ to find its more modern form. For example:

-

- Balduino = Balduini

- Calvetto = Calvetti

- Cazuffa = Cazzuffi

- Chiusola = Chiusole

- Colomba = Colombini (maybe)

- Guarienta = Guarienti

- Micheletta = Micheletti or Micheletto

- Mirana = Marana

- Morella = Morelli

- Nigra = Negra

- Tabarella = Tabarelli

- Ticina = Tecini

- Pratta = Prati

Moreover, certain consonants were more or less interchangeable in the past. A ‘z’, for example could be replaced by a ‘ci’, ‘gi’ or ‘ti’ (and vice versa) depending on the preference of the writer. For example, these names on the list might be more commonly seen thusly (although I must stress that I am only hypothesising here):

-

- Gaudenta = Gaudenzi

- Gratiadea = Graziadei

- Zello = Celli

Lastly, some people appear not to have be recorded by a surname at all; rather, they are identified by their place of origin. For example:

-

- ‘(The family of the Casa) Marazzona’ surely refers to the frazione of Marazzone in Bleggio (Val Giudicarie). There really is only a handful of families living in this village during that era. I haven’t yet tried to figure out who this might be referring to, but I am sure this is what it means.

- ‘Rovereta’ is most likely referring to someone who came from Rovereto.

- ‘Raino’ is most likely referring to someone from that frazione of Raina in the parish of Castelfondo (Val di Non). It is the ancestral home for families like the Genetti.

- ‘Chiusola’ (Chiusole) is both a surname and a place name in Villa Lagarina. The place is the indigenous home of that family. It’s impossible to know from this document alone if it was already used as a formal surname in the early 1500s.

- ‘Paho’ is an early form of the name of a comune now called ‘Povo’, which is in the south-eastern part of the present-day city. A curate parish in existence at last as far back as the year 1131, it was well beyond the city walls when this record was made. The entry refers to them as ‘the family or house(hold) of Paho’. Thus, this label appears to be referring to a property owner in that village.

Article continues below…

Some Trento Surnames Between 1577-1600

As we progress through the list chronologically, names become slightly more familiar to those of us who had worked with Trentino records. Here’s a random sampling of some of the surnames that were entered later, between 1577-1600. I’ve omitted names that were also in the earlier batch, even if they were spelled a bit differently:

Baldessar, Baldino, Baldiron, Basso, Belotto, Bennasu’, Bertello, Bevilacqua, Bonmartino, Brissiani, Busetto, Capri of Vigol Vatta, Cestar of Cognola, Chalianer, Crosino, Cusano, Dori of Oltracastel de Poho, Figino, Galliciolo, Gerardi, Giordani, Gottardo, Guidottino, Iob, Luchio, Malacarne, Martini of Terlago, Migazzi, Montagna, Nassimbeni of the Zudigaria, Novello, Particella, Piber, Ropelle, Sarafin of Villaza de Poho, Tessadri, Torre, Trentini, Vida of Zuzà di Tion, Voltolino.

These names start to ‘feel’ more familiar to me, as they resemble more closely (and in some cases are the same as) the forms of these surnames as I have seen them in the parish records, which started not long before this in the 1560s.

Surnames in the above list that are identical to how I’ve typically seen them written include:

-

- Bevilacqua

- Dori

- Gerardi

- Giordani

- Iob

- Malacarne

- Martini

- Montagna

- Tessadri

- Torre

- Trentini

Many others need only a slight tweak to see their more well-known forms. If we apply the same ‘permutation rules’ we used for the previous batch to some of these names, we see can see:

-

- Baldessar = Baldessari

- Belotto = Belotti / Bellotti

- Bennasu’ = Benassuti (see more below)

- Bertello = Bertolli

- Busetto = Busetti

- Cestar = Cestari

- Crosino = Crosina (see more below)

- Gottardo = Gottardi

- Guidottino = Guidottini

- Luchio = Luchi (perhaps)

- Ropelle = Ropele

- Voltolino = Voltolini

One linguistic permutation we did not see on the earlier list is the interchangeability between ‘ss’ and ‘sc’, if followed by the letter ‘i’. If we apply this along with other needed shifts, we see:

-

- Brissiani = Bresciani / Bressiani

- Nassimbeni = Nascimbeni

In modern Italian, the combination ‘sci’ is pronounced like ‘shi’; a double ‘s’ makes the consonant soft, like the last letters in the word ‘hiss’. It seems likely, these two consonant combinations were pronounced much the same when they appeared before the letter ‘i’ the middle of a word.

Notable Citizens from the Rural Valleys

What I find exciting about this later batch of ‘citizens’ is that I actually recognise a few of the individuals, as they cross into my own family history (although not as direct ancestors). Specifically:

- Messer Thomio Bennasu’ (the accent is part of the name), entered into the book in 1576, refers to Tommaso Benassuti, who came from the noble Benassuti family of Tignerone in Bleggio (Val Giudicarie). Although the record does not give his village of origin, I know it from several other sources, where Tommaso has been cited as a notary who worked in Trento throughout his adult life.

- His Excellency Messer Thomio Crosino, ‘phisico’, who was entered into the in 1585 refers to Dr Tommaso Crosina, a medical doctor from the noble Crosina family of Balbido (also in Bleggio). Again, his village of origin is not mentioned in the book, but his life and ancestry are well documented by many historians and descendants, going back to the 1200s when the Crosinas fled Padova to take refuge in Val Giudicarie.

I am distantly related to both of these men, via lines of their families that stayed behind in Bleggio in rural Val Giudicarie, which is the primary focus of my personal research. As such, I’ve done a fair bit of research on both of these families, albeit not so much after these migrations to the city of Trento.

People and Places

As they started to enter the names of more recent citizens in the Liber, the Consuls became more precise about recording places of residence and/or origin.

Three on the above list are specifically said to come from villages that lie on the outskirts of the city of Trento, and which are today included as part of the greater municipality of the city. I think it’s worth looking at them, as we’ll be talking more about these places in the next article. These are:

-

- Dori of Oltracastel de Poho. ‘Poho’ is another antiquated spelling for the comune (town) of ‘Povo’. ‘Oltracastel’ is a variant spelling for ‘Oltrecastello’, which is a frazione (hamlet) of Povo.

- Sarafin of Villaza de Poho. Here we see the comune of Povo again, but this time the person is from a different frazione: Villaza, which is an antiquated spelling for Villazzano. Villazzano was originally considered to be part of Povo, but it has now been its own comune for some time.

- Cestar of Cognola. Cognola is another comune of the city of Trento. It is a bit north of Povo, on the eastern side of the city.

Other people on this list who are said to have come from places outside the city include:

-

- Capri of Vigol Vatta, i.e. Vigolo Vattaro, a comune east of Trento, about midway between Mattarello and Lago Caldonazzo.

- Martini of Terlago, a comune in Valle dei Laghi.

- Gerardo Nassimbeni (Nascimbeni) of the ‘Zudigaria’, which is an antiquated spelling for (Val) Giudicarie. This surname does appear in Val Giudicarie during this era, but it’s a pretty big valley, and I wouldn’t be able to guess at where he was from. He is described as a ‘host’ which means he owned a taverna or some other kind of accommodation for travellers and pilgrims. As this list of citizens refers to property owners, it is possible he owned the property in the city but kept his home in the rural valley.

- Vida of Zuzà di Tion. ‘Zuzà’ is an antiquated spelling for the comune of ‘Giugia’ in Tione (Val Giudicarie). Although ‘Vida’ is a surname, it’s not one I’ve seen in Tione. My hunch is this man’s surname may actually have been Bonavida, which was present in the villages around Preore and Tione during this era.

- A word about Francesco Brissiani (i.e. ‘Bresciani’) who appears in the book in 1577: Although no place of origin is mentioned for him, we can infer from the name itself that his family originally came from the province of Brescia in Lombardia. This surname appears in many parts of the province, especially those areas in the southwest, which are adjacent to the border with the Brescia. It’s a very old name in Trentino, so how long Francesco’s family had been in Trentino at this time is not something I could possibly guess.

The Fate of the ‘Liber’

In Bertoluzza’s rendition, there is a cross in the left margin next to the names of families that have since gone extinct, which appears to include just about everyone. But, while Bertoluzza doesn’t specify, it seems clear he means the descendants of these families are no longer property owners in the city of Trento, and not necessarily that these families have gone ‘extinct’ altogether.

Sadly, the original intention of the book itself appears to have had a limited impact, as it was not used as fastidiously as the Consuls had mandated. By the 1800s, we see only a handful of names listed, which certainly do not represent all the property owners of the city in that century. Bertoluzza says the Liber appears to have devolved into a register of ‘honorary’ citizens than a true, comprehensive list, even if only of property owners.

Thus, as a source for genealogists, the Liber might be useful to those whose families lived or owned property in the city in the 1500s and early 1600s, but for those whose families were farmers and/or stayed in other parts of the province, it may only hold some historical interest.

Coming Up Next Time

In the next article, we’ll move forward in time, and examine the 1890 Survey of the City of Trento, which is a goldmine of information about the city during the era when many of our ancestors will have migrated from the province.

In that article, we’ll look at the population, surnames, occupations, languages and other demographics of the people living in the city at in the late 19th century. We’ll also explore the civil comuni and neighbourhoods within the municipality of Trento.

Click HERE to read that article now:

After that, we’ll conclude our discussion on the city of Trento with a discussion on the parishes that come under the DECANATO (deanery) of Trento, with details about the records that are available for research in each.

Once we’ve finished our genealogical tour of the city of Trento, we’ll start to move on to our tour of the rest of the province – moving first to an exploration of Val di Non.

I hope you’ll join me in the upcoming stops on the tour of the province in this series ‘Trentino Valleys, Parishes and People: A Guide for Genealogists’. To be sure to receive these and all future articles from Trentino Genealogy, simply subscribe to the blog using the form below.

Until next time!

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

28 April 2020

P.S. As you probably know, my spring trip to Trento was cancelled due to COVID-19 lockdowns. However, I do have the resources to do a fair bit of research for many clients from home, and will have some openings for new clients from 1 June 2020. If you would like to book a time to discuss having me do research for you, I invite you to read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, we can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://trentinogenealogy.com/my-tree/

REFERENCES

ANZILOTTI, Giulia Maistrelli. 2003. Toponomastica Trentina: I Nomi delle Località Abitate. Trento: Provincia Autonoma di Trento, Servizio Beni librari e archivistici.

BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1975. Libro della Cittadinanza di Trento: Storia e tradizione del cognome Trentino. Trento: Dossi Editore.

SCORPIO, Vittoria; SURIAN, Nicola; CUCATO, Maurizio; DAI PRÁ, Elena; ZOLEZZI, Guido; COMITI, Francesco. ‘Channel changes of the Adige River (Eastern Italian Alps) over the last 1000 years and identification of the historical fluvial corridor’. Journal of Maps. Volume 14, 2018, Issue 2. Published 19 Nov 2018. Accessed 27 April 2020 from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17445647.2018.1531074