Genealogist Lynn Serafinn discusses the origins of some of the Martini families of Trentino, including those in Val Giudicarie, Val di Sole, Val di Non and Vallagarina.

This article is also available as a 14-page downloadable, printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, foot notes and resource list. Price: $1.50 USD.

CLICK HERE to buy this article in the ‘Digital Shop’, where you can also browse for other genealogy articles.

Martini is one of many patronymic surnames derived from the male personal name Martino, which Bertoluzza says has the meaning ‘sacred, dedicated to the god Mars’.[1] However, the popularity of the personal name is surely an homage to Saint Martin of Tours, a 4th-century Roman soldier stationed in Gaul (modern-day France), who later became a Catholic Bishop. Amongst Catholics, he is most famous for a legend wherein, having been approached by a scantily-clad beggar, Martin cut his own cloak in half and gave the other half to the destitute man. According to the legend, Martin had a dream that night wherein Jesus came to him, wearing the half of the cloak he had given the beggar. Thus, among his many patronages today, Martin is first and foremost he is the patron saint against poverty.

Like so many other patronymic surnames, Martini is extremely common, not just in Trentino, but throughout the Italian peninsula. As of this writing, There are reportedly over 9,300 Martini families living in just about every province of Italy, with only 191 of these living in Trentino.[2] In Trentino itself, the surname is widely dispersed; the Nati in Trentino website lists 2,762 Martini births in no fewer than 37 different Trentino parishes between the years 1815-1923, with the heaviest concentration in Revò in Val di Non, and a significant number also in parts of Val Giudicarie and Valsugana.[3] Bertoluzza also points out that there is a frazione called Martini In Vallarsa (Val di Leno), which indicates there was an ancient local concentration of the surname there.[4]

While time prevents me from discussing all the Martini families in Trentino, in this article, we will briefly explore the Martini of Ragoli and Santa Croce del Bleggio (Val Giudicarie), and Riva / Calliano (Vallagarina), and then take a more detailed look at the Martini of Peio (Val di Sole), and Revò (Val di Non), including certain lines that were ennobled.

The Martini of Ragoli in Val Giudicarie

When considering the present-day parish of Ragoli, you have to look also in records associated with the comune of Preore, the villages in the area may be associated with either Preore or Ragoli in earlier centuries. You also have to cross-reference events with the records from the parish of Tione di Trento, as Ragoli records can appear in either parish.

Early documents indicate the presence of the Martini family in Ragoli for at least the past 600 years. Priest-historian don Ivo Leonardi tells us of a ‘Martino of Bulzana (a frazione of Ragoli)’, whose name appears in the tithing records (‘decima’) for Preore in 1388, which is before surnames were widely in use. As the Martini family is later often associated with the frazione of Bulzana, he suggests this is an indication of a possible patriarch of the family later bearing the surname Martini.[5] Author Paolo Scalfi Baito tells us of a ‘Pietro, son of the late Martini’ cited in the Statute of Spinale e Manez (which was part of the comune of Preore) in 1410.[6] He further tells us the surname is found in the fragments of the Tione parish records in 1603.[7] Additionally, the surname Martini is included amongst those compiled by notary Orazio Bertelli of Preore, when he was recording the names of families who survived the plague of 1630, which had decimated much of that part of the province.[8] The surname is still present in Ragoli today.

In the journal Judicaria, author Paolo Gasperi has written a short biography of the multi-talented artisan, woodworker and musician, Domenico Martini, born in Ragoli on 19 September 1915, wherein he includes an excerpt of the family tree of the artist, dating back to the late 1500s.[9]

The Martini of Santa Croce del Bleggio in Val Giudicarie

The Martini of Santa Croce del Bleggio are a branch of the Martini of Ragoli. Their patriarch is one Giuseppe Martini of Vigo (a frazione of Ragoli), who moved to Cavrasto in Santa Croce parish sometime after marrying Maria Bertelli (also of Vigo) on 30 April 1764.[10] The couple had at least three sons. After Maria died, Giuseppe remarried Domenica Santoni of Ceniga (parish of Drò)[11], with whom he had at least one daughter, Cattarina Luigia, in 1773.

Not long after the birth of Cattarina Luigia, the Martini family moved from Cavrasto to settle in an area of the parish then called ‘Spiazzo’ (not to be confused with Spiazzo Rendena), which referred to the area near the parish church of Santa Croce, which is not part of a specific frazione. Most Martini in Bleggio continued to reside in ‘Spiazzo’ well into the 20th century.

The sons of Giuseppe and his first wife Maria grew up to have families of their own,[12] thus propagating the Martini surname in Santa Croce, where their descendants still flourish to this day.[13] From this lineage came the renowned vernacular poet Aldo Martini, who was born in Santa Croce on 11 September 1911, and died in 1979.[14]

Article continues below…

The Martini von Griengarten und Neuhof

This line is an ancient Trentino family, known at least since the mid-1500s, originally from Riva, Calliano (Vallagarina), and Mezzocorona.[15] I have not personally researched this family from a genealogical perspective, but I will share what I have gleaned from other historians about their noble titles.

In Innsbruck on 10 May 1566, Archduke and Emperor Ferdinando I conferred noble privileges on Baldassare, Giovanni Maria and Nicolò Martini of Calliano.[16] Later, the Prince-Bishop Domenico Antonio of the Counts of Thun extended these same privileges to the Martini of Riva.[17]

On 13 June 1559, Emperor Ferdinando granted a stemma (coat-of-arms) to a Pietro Martini of Calliano, who was serving as a chaplain in the court in Innsbruck, and extended this privilege also to Pietro’s brothers Cristiano, Melchiore, Giovanni Cristoforo, Valentino and Nicolò, all of Calliano.[18]

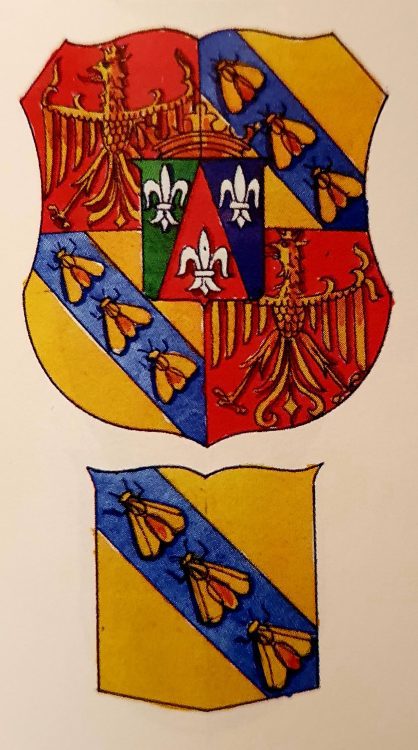

On 5 February 1746, Prince-Bishop Domenico Antonio Thun granted Giovanni Maria and Nicolò Martini permission to add the stemma of the extinct Zanardi family to their own.[19]

On 24 September 1790, brothers Carlo and Giovanni Martini were elevated to the rank of Counts of the Holy Roman Empire, with the predicate ‘von Griengarten und Neuhof’ (sometimes Italianised to ‘de Griengarten e Neuhof’) by the Imperial Vicar, Carol Teodoro. The family were again elevated to the rank of Counts as late as 18 January 1844, by Austrian Emperor, Franz Josef. [20]

The Martini di Valle Aperta of Peio (Val di Sole)

The Martini of Peio in Val di Sole have a long and well-documented history. Tabarelli de Fatis and Borelli tell us that the founding father was one Martino, who came to Peio in the late 1400s, probably from Valtellina in Lombardia, where there was a family of notaries of the same name.[21] Among his sons, we find the notary Giovanni Antonio Martini (cited in records as early as 1545), another notary Giovanni Battista Martini (cited as early as 1550), and the priest Fabiano Martini, who was curate of Peio until his death in 1564.[22], [23]

One of Martino’s later descendants, another Martino Martini (1614-1661),[24] was a Jesuit priest, who, in the 1500s, became the first missionary to go to China. During his extensive travels, he did a detailed study of the geography of the country, which he later published in a work entitled Atlas Cinensis.[25]

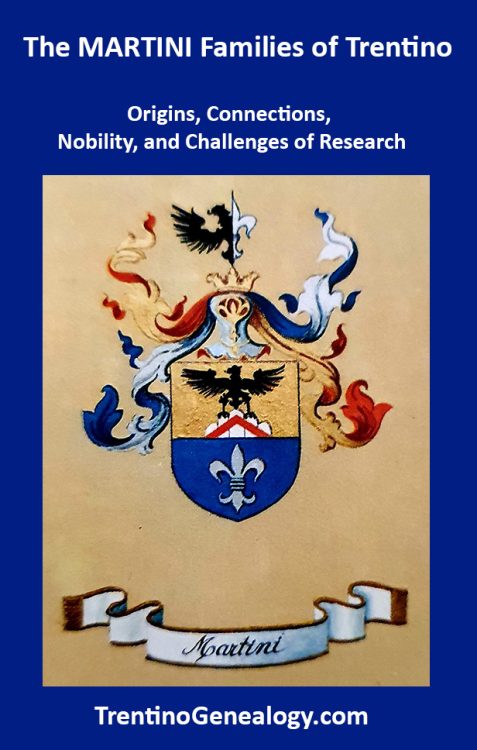

In 1559, the family were granted the right to use a stemma by Emperor Ferdinando I (via one Pietro Martini). They were later granted nobility of the Holy Roman Empire in 1566. [26]

The stemma contains a black eagle sitting on a five-peaked mountain in the upper half, and a silver lily (fleur-de-lis) on a blue background in the lower half.[27]

On 7 January 1580, Prince-Bishop Lodovico Madruzzo granted the use of a stemma to Giuseppe Martini, who was originally of Peio, but was living as a citizen of the city of Trento, where he served as a spice dealer for the principality. Two generations later, the family was granted the imperial predicate ‘di Valle Aperta’ by Maximilian, Prince of Dietrichstein (on the authority of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III) on 27 November 1641.[28]

The priest, Antonio Martini di Valle Aperta (sometimes abbreviated V. A. in documents) of Peio, was parroco (pastor) of the parish of Revò in Val di Non from 17 December 1647[29] until his death on 5 April 1666.[30]

The notary Gerolamo Martini di Valle Aperta of Peio spent most of his long life in the city of Trento, where he served as the secretary to at least five Prince-Bishops until at least 1680. [31], [32]

A branch of the Martini di Valle Aperta of Peio moved to Salorno in South Tyrol. From this line, one Giovanni Antonio, a merchant, later transferred to the city Trento, where he was elevated to the rank of Knight of the Holy Roman Empire (Cavaliere del S.R.I.) on 30 September 1790 by Carlo Teodoro (Charles Theodore), Elector of Bavaria.[33]

At least until the late 20th century, a tomb of the Martini di Valle Aperta family, engraved with their stemma and dated 1652, was still visible facing the main altar in the parish church of Peio.

The Martini of Revò (Val di Non)

Nearly every historian I have consulted says the branch of Martini of Revò who later became the noble Martini de Wasserperg (also seen spelled ‘Wasserberg’) were originally a branch of the Martini di Valle Aperta of Peio, who settled in Val di Non at least by the late 1400s.[34] However, in none of these histories have I found any reference to documentative evidence specifying the name of the man who migrated to Revò from Peio, nor precisely when he did so.

The surname Martini has been part of the Revò landscape for as long as surviving records narrate. We surely find it in the earliest baptismal records of the parish register, which starts in 1619. Other records, such as the Revò tax register from 1620[35], and the census of 1624[36], tell us that there were four Martini households present in the first decades of the 17th century, with no indication that they (nor any of the elders who were born in the mid-1500s) were newcomers to the parish. Thus, if the Martini of Revò had indeed migrated from Peio, we might safely assume that they arrived by the beginning of the 1500s, which does fit with most historical estimates.

However, what is more difficult to ascertain is whether ALL of the Martini families living in Revò at the beginning of the 1600s were descendants of the said immigrants from Peio, or if there were pre-existing Martini families already living in Revò before their arrival.

Thus far, I have not found any evidence that can conclusively answer these questions. However, there may be some possible clues when we look closely at two particular households the 1624 census and the 1620 tax census:

- The household of Margherita (age 52), the widow of the late dominus Domenico Martini. The record indicates the house once belonged to Domenico and Margherita’s son, Francesco, who is also deceased. Living with her is her daughter, also named Margherita, who is 25 years old, and also widowed. With them are the younger Margherita’s two children: Domenica (born 1622) and Antonio (born 1623). Her late husband, Antonio Vielmetti was a notary from Preghena in the parish of Livo. He died before the birth of their son Antonio, after which she returned to Revò to live with her mother.

- The household of Giovanni de Martini, who was widowed shortly before the 1624 census, and is now living with 7 of his children (who range in age from 4 to 29), including his 29-year-old son Giovanni Francesco, who was a priest. Believe it or not, I have found more than one young priest living at home with his parents rather than at the church rectory.

There are two reasons why these stand out to me.

One is the use of honourifics when referring to members of these two households. The 1624 census refers to these families (along with one other) as ‘de Martini’. The prefix ‘de’ is generally reserved for noble lines. Also, Giovanni Martini as well as Margherita’s late husband Domenico are referred to as ‘dominus’ (but abbreviated), which is a general honourific used for a man of some social status. While this honourific alone does not always indicate nobility, it can sometimes infer it. Similarly, when his daughter Margherita Martini is a godmother in 1619, she is referred to as ‘Madonna’ (My Lady), which is generally only used in cases of nobility. [37]

The other reason is the apparent wealth of these two households, as per the tax census. Where the majority of households in the parish are reported to have perhaps around 10 bushels of grain (and many with none), the widowed Margherita is reported to have 150, and ‘dominus‘ Giovanni de Martini has 100.

This combination of honourifics and wealth makes me inclined to suspect these two families may have been nobility, and may also have been related. Perhaps Giovanni was the brother of Margherita’s late husband, for example. Perhaps, as they both had sons with the name Francesco, they were the sons of another Francesco. Of course, this is all speculation.

Article continues below…

Carlo Ferdinando Martini de Wasserperg

Aside from these questions of origins, one thing we can definitely prove through documentation is that the noble line known as ‘Martini de Wasserperg’ are descended from the wealthy Giovanni de Martini mentioned above.

Of his 7 children, 6 were male (albeit one was a priest). While I have not researched all of these children, his son Federico, born around 1616, had at least 7 sons, and Federico’s son Pietro had at least 6. In this way, the Martini surname flourish in Revò throughout the 17th century.

Pietro’s son, Carlo Ferdinando Martini, was born 20 May 1669. In his baptismal record we see that his godfather Carlo Ferdinando, one of the Counts of Thun. As this is the first time that we see this name ‘Carlo Ferdinando’ appear in the Martini lineage, I can only assume he was named after his noble and influential godfather. By age 26, when he marries Margherita Graiff of Romeno on 09 February 1695, Carlo Ferdinando is working as a notary.[38] By 1708, we begin to see him referred to as ‘noble’ in the parish records. [39]

IMPORTANT: I would like to stress that this is the FIRST time any Martini family is referred to as nobility in the Revò records, and this is the ONLY Martini family group consistently referred to as nobility, even amongst those who may also be descended from the wealthy dominus Giovanni de Martini we met in 1620. So, even if the entire line had an ancient noble origin (possibly via a connection to the Peio Martini), that connection was no longer recognised ‘across the board’ by the year 1700.

Carlo Ferdinando and Margherita Graiff had a son who was ALSO named Carlo Ferdinando. it is this younger Carlo Ferdinando who became the founding father of the Martini de Wasserperg line.

This younger Carlo Ferdinando was born in Revò on 09 December 1704. Most likely born ennobled, he followed his father’s profession as a notary.[40] At age twenty, he married Margherita de Pretis of Cagnò on 30 April 1724, who was herself descended from two different noble de Pretis lines.[41] Again, this couple had a large family, producing at least 5 sons and 6 daughters.

On 25 June 1765, Carlo Ferdinando and his eldest son, Carlo Antonio Martini, who was then a Professor and Director at the University of Vienna, were both elevated to the rank of Knights of the Holy Roman Empire (‘Cavalieri di S.R.I.’), when they were also granted the use of the predicate ‘de Wasserperg’ (also seen ‘von Wasserberg’).[42] Aside from the use of the fleur-de-lis, their stemma bears no resemblance to that of the Martini di Valle Aperta in Peio.

On 14 March 1771, Carlo Ferdinando also obtained ecclesiastical nobility from Prince-Bishop Cristoforo Sizzo de Noris.

Not long afterwards, he died from a sudden illness on 10 January 1774, shortly before his 70th birthday. He was buried in a family tomb inside the parish church of San Stefano. [43]

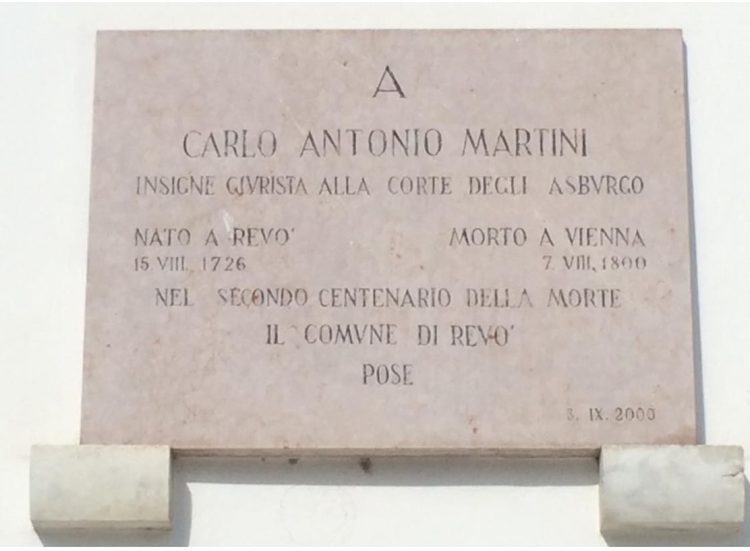

Carlo Antonio Martini de Wasserperg

Without a doubt, the most famous of all Trentino Martini is Carlo Ferdinando’s son, Carlo Antonio Martini de Wasserperg.

Carlo Antonio Martini was born in Revò on 15 August 1726.[44] Historian Roberto Pancheri tells us that Carlo Antonio first embarked on an ecclesiastical career, attending the Jesuit College in Trento, and also studied theology and law in Innsbruck. As per his father’s wish, he took on the Capuchin robe, but later abandoned the order. [45], [46]

Pancheri further explains that, in 1747, against the wishes of his family, Carlo Antonio transferred to Vienna to dedicate himself to the study of philosophy and law, eventually obtaining a doctorate. Becoming the secretary of the court adviser of Count Friedrich von Haugwitz, and subsequently Chancellor of the State, he began his long career in the inner administration of the Hapsburgs.

In 1752, he went to Madrid, following the Ambassador of Austria, the future Cardinal Cristoforo Migazzi, who was also from Trentino. Upon returning from this important mission, he was assigned the desk of natural Law and Institutions at the University of Vienna.

Among his many high-ranking roles, he was President of the Supreme Court of Justice in Vienna, and was in charge of compiling the ‘Codex Theresianus’ for the Empress Maria Teresa.[47] Written in German, the Codex was an expression of the Empress’s personal mission to reform the legal system, specifically the Law of persons, the Law of property, and the Law of obligations. Although never officially put into place, many historians laud it as a major ideological step forward compared to other European legal systems of its time.[48]

In addition, the Empress also engaged Carlo Antonio to instruct her children, and especially her son, the Archduke Leopoldo, who later became Emperor in 1790, after having been Grand Duke in Tuscany. He also prepared the first projects of mass education for the subjects of the Empire, reorganising the elementary schools and the universities. Alongside, this, he also deepened the legal and penal system, and became a member of the court commissions for Censorship, for Studies, and for Ecclesiastical Affairs.[49]

On 1 December 1780, he was elevated to the rank of Baron of the Holy Roman Empire, with an elaboration of the stemma, by Emperor Giuseppe (Josef) II. The family was entered into the matriculation of noble Tirolesi in 1783. [50]

In 1792, he was put in charge of presiding over the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, the highest judiciary rank in the Empire. He improved the justice system in Lombardia, during the time of Hapsburg rule, and prepared the civil code of Galizia and modernised the penal codes of Austria. In 1797, three years before his death, for reasons of health, he resigned from the Court Commission on Legislation. [51]

He died in Vienna on 8 August 1800.[52] Although he had two sons, Massimiliano and Paolo, both died without offspring, which brought an end to the noble Martini de Wasserperg line. [53]

In the year 2000, the parish of Revò erected a memorial stone commemorating the bicentenary of his death.

Soprannomi, and the Many Martini in Revò

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, Revò is where you will still find the greatest number of Martini in Trentino today. And, from experience, I will tell you that wading through all those Martini lines can be a real challenge when you are doing genealogical research, especially if the priests are inconsistent (e.g., alternately calling a man Giovanni Antonio, Giovanni or Antonio), or incomplete (e.g., not including the names of fathers in marriage records, or the surnames of mothers in baptismal records, etc.).

One device the Martini themselves have implemented in an effort to keep all these lines straight are soprannomi, which I describe as ‘bolt on’ names, which Italian families use to distinguish one line from another with the same surname. If you are unfamiliar with soprannomi, you might wish to read my article on this subject entitled ‘Not Just a Nickname: Understanding Your Family Soprannome’.

With regards to the Martini, a group of Revò Martini descendants recently gave me a list of no fewer than 17 different Martini soprannomi, which of course, represent 17 different Martini lines. But sadly, while there are some Trentino parishes (Tione di Trento comes to mind) where soprannomi are meticulously recorded in nearly every record, Revò is just not one of those parishes, and soprannomi are recorded somewhat erratically. I have found many early soprannomi for other Revò families in the records (Rigatti, Geronimi, Magagna are three examples), but I have found hardly any soprannomi for the Martini prior to the 19th century.

Moreover, soprannomi are not as stable as surnames; they change with the times, and new soprannomi will crop up whenever the lines get too tangled again. Thus, soprannomi that may have been in use for the past century (or even two), may not have existed more than a handful of generations, and thus may not lead us very far back in tracing our ancestry.

Thus, there really is no other choice but to trawl meticulously through the parish records and, if necessary, to construct parallel lines of every family with your surname, comparing every tiny detail. Only through such exhaustive (and sometimes exhausting) research can you confirm (or at least make informed theories about) who is who.

But, as I pointed out earlier, one thing we DO know is that ALL of these Martini lines will inevitably lead back to one of the four households we ‘met’ in the 1624 census, for the simple reason that there were no other Martini in Revò. So, if you are a Martini of Revò, it is highly probable you are related to other Martinis, even if your lines have different soprannomi.

And, of course, all four of these Martini lines may or may not take us back to a single Martini from Peio, who came to Revò sometime in the 1400s. If and when that can be proven either through documentation or Y-DNA, we might discover that all Martini from Val di Non and Val di Sole are ultimately cousins.

======

This article is also available as a 14-page downloadable, printable PDF, complete with clickable table of contents, colour images, foot notes and resource list. Price: $1.50 USD.

CLICK HERE to buy this article in the ‘Digital Shop’, where you can also browse for other genealogy articles.

This research is part of a book in progress entitled Guide to Trentino Surnames for Genealogists and Family Historians. I hope you follow me on the journey as I research and write this book; it will probably be a few years before it comes out, and it is likely to end up being a multi-volume set.

If you liked this article and would like to receive future articles from Trentino Genealogy, be sure to subscribe to this blog using the form below.

Until next time!

Warm wishes,

Lynn Serafinn

26 January 2022

P.S. Sadly, due to personal health reasons (not COVID), I have had to cancel my previously arranged trip to Trento for February-March 2022.

THE GOOD NEWS IS: I have MANY resources for research here in my home library, and I am able to do research for many clients without having to travel to Trento. I am now taking bookings for April 2022 and beyond.

If you would like to book a time to discuss having me do research for you, I invite you to read my ‘Genealogy Services’ page, and then drop me a line using the Contact form on this site. Then, we can set up a free 30-minute chat to discuss your project.

Join our Trentino Genealogy Group on Facebook: http://facebook.com/groups/TrentinoGenealogy

Lynn on Twitter: http://twitter.com/LynnSerafinn

View my Santa Croce del Bleggio Family Tree on Ancestry:

https://trentinogenealogy.com/my-tree/

REFERENCES

[1] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino, page 215.

[2] Cognomix website. ‘Martini’. Accessed 24 January 2022 from https://www.cognomix.it/mappe-dei-cognomi-italiani/MARTINI.

[3] Nati in Trentino website. Accessed 25 January 2022 from https://www.natitrentino.mondotrentino.net/

[4] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino, page 215.

[5] LEONARDI, Ivo (don). 1989. La Decima di Preore (Ragoli e Montagne). Trento: Grafiche Artigianelli.

[6] BAITO, Paolo Scalfi. 1987. Preore in Giudicarie: Altre Notizie e Toponomastica. Volume 2. Trento: La Grafica, page 156.

[7] BAITO, page 161.

[8] BAITO, page 162-163.

[9] GASPERI, Paolo. 2000. ‘Domenico Martini: Artigiano e artista in una famiglia dedita alla lavorazione del legno. Judicaria, n. 44, August 2000, pages 69-73.

[10] Ragoli parish records, marriages, volume 1 (LDS microfilm 1447996, part 4, Trento file 4256253_00233), no page number.

[11] Drò parish records, marriages, volume 2 (LDS microfilm 1448195, part 13), page 37. Trento file 4256291_01963.

[12] Especially prolific was Giuseppe’s son Giovanni Martini, who had at least 10 children with his wife, Maria Cattarina Maijerhof.

[13] This information is based on my own research, using the parish records for Santa Croce and Drò. I have not yet fully researched this family.

[14] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino, page 215.

[15] GUELFI, Adriano Camaiani. 1964. Famiglie nobili del Trentino, page 80-81.

[16] GUELFI, page 80-81.

[17] GUELFI, page 80-81.

[18] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano, page 189.

[19] Images of both versions of the stemma are taken from TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano, page 359.

[20] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano, page 189.

[21] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano. 2005. Stemmi e Notizie di Famiglie Trentine. Trento: Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche, page 188.

[22] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano, page 188.

[23] STENICO, P. Remo. 2000. Sacerdoti della Diocesi di Trento dalla sua Esistenza Fino all’Anno 2000, page 269.

[24] BERTOLUZZA, Aldo. 1998. Guida ai Cognomi del Trentino, page 215.

[25] SPRETI, Vittorio. 1928-36. Enciclopedia storico-nobiliare italiana: famiglie nobile e titolate viventi riconosciute del R. Governo d’Italia, compresi: città, comunità, mense vescovile, abazie, parrocchie ed enti nobili e titolati riconosciuti. Milano: Ed., volume IV, page 437. NOTE: the quote was copied and pasted by Pier Carlo Omero Bormida on the ‘I Nostri Avi’ website in 2004, which I accessed on 23 January 2022 at http://www.iagiforum.info/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=493

[26] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano, page 188. I

[27] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano, stemma from page 359.

[28] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano, page 188.

[29] Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 1 (LDS microfilm 1388681, part 6), page 1. There is a fragment of a record at the beginning of the baptismal register that lists the start dates of the parroci. The day and month are clear, but the year has been gleaned from context in other records.

[30] Revò parish records, deaths, volume 1 (LDS microfilm 1388682, part 3), no page number.

[31] TURRINI, Fortunato. 1996. Carte di Peio. Centro Studi per la Val di Sole, page 23.

[32] STENICO, P. Remo. 1999. Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845. Trento: Biblioteca San Bernardino, page 228.

[33] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano, page 188.

[34] This opinion is shared by Tabarelli de Fatis/Borrelli, Bertoluzza, Spreti, and probably others.

[35] Capsa 9, 169 1620 Tax Census (Revò, Cloz, Dambel, Romeno, Fondo, Livo, Bozzana), page 1-4.

[36] Revò parish archives, anagraphs, pages 73, 74, 76, 84 (Revò, 28 July 1624).

[37] Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 1 (LDS microfilm 1388681, part 6), page 2-3.

[38] Carlo Ferdinando (the elder) is referred to as ‘spectabilis’ in his marriage 1695 record, and in later records. This is an honourific used specifically for notaries. Revò parish records, marriages, volume 1 (LDS microfilm 1388681, part 16), no page number.

[39] Carlo Ferdinando (the elder) is first referred to as nobility in the baptismal record of his son Giovanni Romedio, on 21 February 1708. Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 3 (LDS microfilm 1388681, part 8), page 6-7.

[40] P. Remo Stenico’s Notai Che Operarono Nel Trentino dall’Anno 845, page 227

[41] Revò parish records, marriages, volume 2 (LDS microfilm 1388681, part 17), page 39. Marriage of Carlo Ferdinando Martini and Margherita de Pretis (30 April 1724). I have also traced both sides of Margherita’s family.

[42] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano, page 188. Stemma on page 359.

[43] Revò parish records, deaths, volume 3, page 112.

[44] Revò parish records, baptisms, volume 3 (LDS microfilm 1388681, part 8), page 216-217.

[45] PANCHERI, Roberto. 2000. Carlo Antonio Martini. Ritratto di un giurista al servizio dell’Impero. Trento: Edizioni U.C.T.

[46] A similar, if slightly more detailed, biography for Carlo Antonio can be found (in Italian) entitled ‘Carlo Antonio Martini de Wasserperg’ at https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlo_Antonio_Martini. The public domain portrait above, painted by an unknown artist, was also taken from that website.

[47] SPRETI, Vittorio. 1928-36. Enciclopedia storico-nobiliare italiana: famiglie nobile e titolate viventi riconosciute del R. Governo d’Italia, compresi: città, comunità, mense vescovile, abazie, parrocchie ed enti nobili e titolati riconosciuti. Milano: Ed., volume IV, page 437.

[48] Codex theresianus. Wikipedia (Italy). Accessed 25 January 2022 at https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex_theresianus.

[49] PANCHERI, Roberto. 2000. Carlo Antonio Martini. Ritratto di un giurista al servizio dell’Impero.

[50] TABARELLI DE FATIS, Gianmaria; BORRELLI, Luciano, page 188.

[51] PANCHERI, Roberto. 2000. Carlo Antonio Martini. Ritratto di un giurista al servizio dell’Impero.

[52] PANCHERI, Roberto. 2000. Carlo Antonio Martini. Ritratto di un giurista al servizio dell’Impero.

[53] SPRETI, Vittorio. 1928-36. Enciclopedia storico-nobiliare italiana: famiglie nobile e titolate viventi riconosciute del R. Governo d’Italia, compresi: città, comunità, mense vescovile, abazie, parrocchie ed enti nobili e titolati riconosciuti. Milano: Ed., volume IV, page 437.